In the beginning, there was gruel-beer. The epoch: sometime before the dawn of civilization, as hunter-gatherers in the Tigris and Euphrates valleys were just starting a flirtation with grain. These ancestors of the Sumerians had discovered that soaking grain in water softened it, forming a thin gruel. Over time they made refinements, learning to crush the grain and soak it in hot water—an innovation that released some of the grain’s sugars and made a thicker, sweeter porridge. At some pivotal moment, humankind stumbled into one of those happy accidents that change the course of history. A bowl of gruel, perhaps secreted away in the cluttered cave of a teenager, sat out a night or two in the yeast-laden air. It fermented into a mildly intoxicating soup—what archaeologists call “gruel-beer”—and thus began the history of brewing.

There are three ways to think about what comes next. If we tell the story one way, it leads into the history of civilization, how humans decided to settle down, till the soil, found monotheism, and ultimately invent the iPhone. A more narrow telling of the story focuses on the history of brewing: how humans learned to malt the grains, mash them, add hops, and finally, thousands of years later, discover the existence of yeast. A third thread highlights the way in which peoples and beer evolved together, how beer styles reflected the people who brewed them.

Of course, we don’t have to choose. All three are the story of beer, which has been a part of our history since the dawn of civilization. It has become tightly embroidered into our culture. When you start plucking up specific styles of beer, you haul up dozens of stories about the local agriculture, laws, wars, and technologies that shaped them. Why is a stout dark? Why are märzens named for a month (March)? Why is lambic sour? Just one question about one beer precipitates a story that, told fully, is the biography of the people who brewed it. ■

TAKE THE 1936 vintage of Coronation Ale I have in my cellar. The English brewery Greene King brewed it specially to celebrate the ascension of Edward VIII to the throne. This was not unusual. For centuries, people had been making celebratory beer—the word “bridal,” for example, derives from the Anglo-Saxon bry¯d-ealo (“bride ale,” which actually refers to the celebratory fest, not just the beer). If you recall your royal history, though, you know that the coronation of 1936 was unusual: It never happened. Edward, after a reign of just 325 days, decided he would rather marry the American divorcee Wallis Simpson than continue on as King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and of the British Dominions and Emperor of India. The beer, a dark, relatively low-alcohol beer, sat in cellars in Bury St Edmunds for decades.

This bottle of Greene King Coronation Ale shows its age.

What does this beer tell us about Britain at the time? Quite a lot, actually. In centuries past, a batch of celebratory beer might have been rich and alcoholic. Breweries at English universities made “audit” ales for the feast celebrating the end of the annual exams. (Greene King made one of those, too.) In earlier times, the nobility competed to make the strongest beers, sometimes to celebrate the birth of a child or a wedding. Why didn’t Greene King make a beer like this for the future king? Beers had changed. Even thirty years earlier, 5%—the ABV of this beer—would have placed it among the weaker beers available in Britain. Standard strengths from Victorian times through the early twentieth century were around 6%, and a good many beers were stronger than 8% (standard Budweiser is 5% ABV).

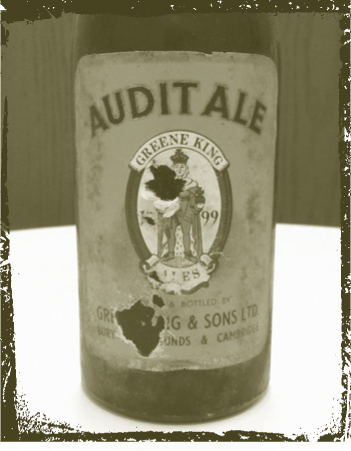

School’s out for summer: Greene King’s celebratory Audit Ale

So the question arises: Why was the 1936 Coronation Ale so weak? During the First World War, the British government put controls on the amount of grain breweries could use, and strengths collapsed. All of a sudden, beers below 3% ABV were common. As the country climbed out of the postwar hole, strengths recovered a bit—which is the moment Greene King brewed Coronation Ale. Soon, the machines of war started grinding in Europe again, and strengths would again fail. The period of mandated low-strength beer lasted so long that the British developed a taste for it; even today, beers are nowhere near as hearty as they were before World War I. Celebration Ale is a fun example because it involves eloping monarchs, but every beer has its story.

Even conservative taxonomists will divide beer styles into dozens of distinct categories. Each one has a unique story. It’s possible to draw a line from gruel-beer to Coronation Ale, but to connect gruel-beer and Pilsner Urquell requires an entirely different line. Climate, laws, war, technology, trade, and even religion have guided and shaped the way beers have morphed and changed. Styles evolved in increments, traveled and influenced other styles, and many times waned and flickered out. Yet all emerged because of certain conditions that were as specific and unique as the beer itself—and all are, even today, continuing to evolve. What follows is an overview of that process—a primer for understanding how civilization developed brewing, where styles came from, how they evolved, and why they persist. ■

NOW, back to that gruel-beer. Scholars suggest the first batches were enjoyed in roughly the years from 10,000 to 8000 BCE. In the Fertile Crescent, wild grain was abundant; people could release the seeds just by beating the grasses. Archaeologists suspect that ancient brewers were already developing the basic process of brewing by transferring batches of gruel-beer from clay pot to clay pot, unknowingly selecting and isolating yeast strains that lived in the pots’ cracks and fissures. Gruel-beer was made from unmalted grain and would have been quite weak—one to two percent alcohol at most.

Eventually, beginning around 4500 BCE, the nomadic people we now call the Sumerians settled down. The impulse may have come from rapid population growth, or because people became increasingly tired of hauling around newly invented implements. Certain avid beer fans argue that agriculture began because the growing population couldn’t rely on wild seeds and they just had to have a regular supply of beer. (Archaeologists tend to favor bread making as the more likely motivation.)

There have been three revolutionary discoveries in brewing: malting grain, the use of hops, and the function of yeast. The first and biggest leap, malting grain, was taken so early it went unrecorded. At some point, humans discovered that germinated grain produced stronger beer than its raw counterpart. By the time of the first records of beer, people were already using advanced brewing techniques: malting and kilning grain and mashing it to make beer. In those oldest writings, Sumerians describe a beer recognizable to modern eyes as beer—much more rustic, but malted, kilned, mashed, and fermented.

Beer’s Epic History.

“You are the one who waters the malt set on the ground …

Ninkasi, you are the one who soaks the malt in a jar The waves rise, the waves fall …

You are the one who spreads the cooked mash on large reed mats, Coolness overcomes …

Ninkasi, you are the one who holds with both hands the great sweet wort.”

—HYMN TO NINKASI, 1800 BCE, translated by Miguel Civil

“‘Eat the food, Enkidu, it is the way one lives.

Drink the beer, as is the custom of the land.’

Enkidu ate the food until he was sated,

he drank the beer—seven jugs!—and became expansive and

sang with joy!”

—EPIC OF GILGAMESH,

circa 2500 BCE, translated by Maureen Gallery Kovacs

As hunter-gatherers, small tribes were able to collect and hunt enough food to enjoy leisure time, which in turn led to relatively democratic societies. Diets were varied and healthy. By contrast, field work took huge effort, burning up to 5,000 calories a day. For their trouble, people made due with a less healthy, less varied diet. And the need for reliable, subservient labor brought societal stratification. To support this new life, the Sumerians had to consume more calories than they could get from bread alone. Beer—more energy-dense than bread—was consumed in huge quantities, and was drunk liberally by most Sumerians once they exited infancy. If beer wasn’t the only reason people decided to take up agriculture in the first place, it was one of the main reasons they were able to continue once they had. No doubt beer’s narcotic benefits helped loosen muscles and soothe minds after long days in the field—and probably helped quell rebellion.

The First Beer Styles From the very start, beer was made in different styles. One especially detailed list from Sumer lists beer by age, color, quality, and recipe. One type of beer had lots of spelt and no wheat, while another had lots of wheat and no spelt. Egyptians also had at least seventeen different beer types, including some evocative varieties like “joybringer,” “heavenly,” “beer of the protector,” and “beer of truth” (though that one was just for the gods).

Sumer wasn’t the only civilization that developed beer; many early cultures across the world started brewing soon after they sowed their first fields. The Egyptians, who were just slightly later than the Sumerians, are the most famous early brewers. Evidence suggests pre-literate brewing as early as 5000 BCE, and written records begin around 3100 BCE. Beer was a central part of Egyptian culture, from its ubiquity in daily diets to its use as an offering to the gods and the dead. Egypt was the first place to tax beer and likely the first place to export it.

Egyptians operated sophisticated breweries. They malted their wheat and barley and dried it in the sun, ground it, and used a two-phase system of mashing it. One of their early innovations was to add dates and pomegranates to flavor the beer. Brewing was integrated into life, where beer served as one form of payment, and—as the clay pots in tombs illustrate—important after death as well.

Elsewhere, brewing wasn’t far behind. In Scotland people might have been brewing as early as the Egyptians. Recent archaeological evidence places both malting and brewing at some time between 4000 and 2000 BCE. These brewers may have been the most fanciful, fortifying their beer with honey and cranberries as well as a variety of wild herbs. Celts started brewing at least by 700 BCE; they not only learned to malt grains, but developed techniques to kiln-dry and roast it. They also added henbane, a toxic psychoactive herb that might have been used to flavor the beer—or make it more intoxicating. Scientists discovered an advanced brewery near present-day Berlin dating to 500 BCE.

Settlers near the Yellow River in China around 220 BCE also brewed, but they had to contend with less-nitrogen-rich soil. (The date is in dispute; some archaeologists argue brewing in China started as early as 9,000 years ago, or roughly the same period as the earliest Mesopotamian brewing.) Their grain of choice was millet, which tolerated the soil’s conditions and also made a nutty brew. The Chinese spiced their beer with herbs, producing a product so popular that local leaders eventually had to pass laws to suppress drunkenness.

In Africa, people harvested millet as well—and sorghum, a grain still used in the production of local beer. The first use of sorghum, around 400 BCE, started south of Lake Victoria in what is now Tanzania and spread farther south as the Bantu speakers continued to look for new fields. Sorghum beer has been continuously brewed in sub-Saharan Africa ever since, in much the same traditional way. The more traditional variety is still brewed by hand using unrefined methods and is sold fresh in local bars, in addition to the large trade in commercial sorghum beer.

In what is now Mexico and Guatemala, the Mayans started making beer out of corn, probably around 150 BCE. Like the other early brewing societies, the Mayans first made a weak beer called chicha by adding cornmeal to warm water, but in one of the more remarkable (and perhaps unappetizing) developments, they also discovered that if they chewed the meal first, the resulting beer was stronger. The mouth contains salivary amylase, an enzyme that helps convert starches to sugar; the Mayans were performing a unique method of early malting. Like sorghum beer in Africa, chicha didn’t die out with the Mayans, and continues to be made in Central and South America.

Those are just some of the main highlights. People across the planet, in what are now Russia, Scandinavia, Central Europe—pretty much wherever grain was a major staple—made beer. At the early stages of development, the kind of beer people made depended wholly on what grew locally. Wheat, barley, millet, sorghum, and corn defined the beers of the Egyptians, Sumerians, Chinese, Africans, and South Americans respectively. Russian and Scandinavian brewing came later than the first wave, but again, the beer they made was based on their local grain, rye.

Modern utwala beer, a traditional ale of South Africa, is made almost exactly the same as it was thousands of years ago. Unlicensed breweries malt their own grain (which may also include corn) and prepare the beer over the course of two days, adding infusions of flour and boiling the preparation periodically. After a short period of fermentation, the milk-colored, flour-silted beverage is ready to drink.

The first few thousand years of brewing were fairly uneventful. After brewers figured out malting and mashing, they bumped along making traditional beer. They pretty quickly learned to add herbs and spices to make beer tastier and sometimes they used other sugar sources like fruit and honey to give their beers a bit of kick. But for the most part, brewing remained a domestic chore that people did on a small scale, following the same practices, one generation to the next. ■

IN EUROPE, things advanced more slowly than they had in Egypt. It would take centuries for beer to reach Egypt’s level of organization, and centuries more for beer to finally start to take a modern form. The biggest barrier was decentralization: Until the 700s CE, brewing was a domestic activity, not a commercial one. There were no specialized brewers, just farmers who made beer as one of the many tasks on the annual calendar.

Brewing continued like this from well before the time of Christ until things finally got going in the Middle Ages. In the eighth century, under Charlemagne, monasteries spread across Europe by the hundreds. The monastic life was shaped by a code, the Rule of Saint Benedict, drawn up around the year 529. It was a complete treatise on the spiritual conduct and operation of a monastery, running to seventy-three chapters. Among the practical effects were monastic self-sufficiency and industriousness (the code also exhorted monks to be cheery). As part of their spiritual practice, monks needed to support themselves, so monasteries managed large farms to grow food—and make wine and beer as well. Furthermore, the Rule encouraged an outward focus of welcoming guests. Monasteries made beer to slake the thirst of their members, but beer also made for a nice offering to visitors. Monks controlled all the stages of production, from maintaining the barley fields on their property to brewing, and consumption of the finished product.

Workers at the historic Brouwerij Rodenbach in Flanders

Over time, monasteries became centers of considerable activity. Growing and malting grain and brewing beer met the standard for self-sufficiency, and the beer they made was an important feature of hospitality (particularly given the state of drinking water at the time). Based on blueprints that still survive for a Swiss brewery-monastery, some of these institutions produced more than a thousand barrels of beer a year—a substantial step up in scale from the farmhouse brewery. In order to make such a large volume of palatable beer, monasteries made technical improvements to their equipment and methods. Because of their size and regular production, monasteries could make better, more consistent beer than the average farmer. At their peak, six hundred monasteries were brewing beer across Europe. This was the first major advance in brewing in centuries.

Stages of Development. In his book Beer in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, University of British Columbia historian Richard Unger adapted a theory of development that is quite handy in understanding the various stages of European brewing. The first stage was domestic production, done in the home on provisional, seasonal equipment. It was the practice for hundreds of years, from the time of scattered brewing activity a few hundred years BCE until the eighth century CE. This evolved into a similar stage where brewing was still done in the home, but became a professional trade conducted on more permanent equipment by more skilled brewers, usually to supplement family income. During both of these stages, the brewers were women and the work was seen as domestic activity. Women continued to brew at home in a semicommercial arrangement until the nineteenth century—a kind of shadow to official commercial brewing later done by men.

The next stage began when brewers established full-time, stand-alone facilities. This stage was a function of urbanization, when skilled craftsmen gathered together to pool their resources and labor, and was the first wholly commercial stage. It’s also when brewing began to gain some social status—which of course is the moment men decided to horn in and displace women. The final stage was manufacturing, when breweries became large-scale enterprises capable of producing a substantial amount of beer for distribution and even export.

One thing to note is that these stages weren’t successive; they skipped forward and overlapped, and sometimes even regressed. There might have been major manufacturing happening in a town while a few kilometers out in the countryside, you saw farmhouse production taking place. It’s also fascinating to note that with the huge popularity of homebrewing and the recent phenomenon of nanobrewing, all stages are once again active.

There were a number of intersecting societal forces at work, and like so much else in this story, beer played an important role. Laws began to shape the way beer was made toward the end of the tenth century, as the government under the Holy Roman Emperor conceived an ingenious scheme to tax breweries. For millennia, brewers had added crushed herbs and spices—gruit—to their beers. According to the new plan, the government would retain the right to sell brewing spice to brewers—functionally, a way of taxing them. Emperor Otto II began to grant the right to collect the tax to loyal nobles or even to towns and this is the context in which the word “gruit” was introduced; the right to provide it was called the gruitrecht. Like water rights, once a recipient had gruitrecht, he could lease it out to others. Gruiters had their own recipes for gruit mixtures, and brewers were mandated by law to buy spices from these vendors. The law lasted for more than five centuries—well into the age of hops (which, inevitably, prompted the levy of hoppegeld, or hop tax). For centuries, then, control of the flavor of beer was dependent on agents who didn’t even brew themselves—all as a scheme to support the activities of local government.

Gruit. From the juniper of Finnish sahti to the heather of Scottish ale, almost every imaginable flavoring found its way into beer. (One recipe for mum, an obsolete English beer, called for the inner rind of a fir tree. Tasty!) The gruit houses of medieval Europe relied on a more limited range of spices, though. Among those mentioned most often are wild rosemary, laurel leaves, sweet gale or bog myrtle, and yarrow, which is even to this day sometimes called “field hop.” Beyond the main ingredients, gruit might have any number of other spices for flavor: ginger, cumin, star anise, marjoram, mint, and sage, to name a few. Other ingredients like laurel and alder bark were sometimes added as preservatives. The proportions were left to the gruiter, who carefully guarded his own personal recipe.

Commercial brewing began in the eleventh century as people began moving off their farms and into towns. Even though it remained a domestic practice in the countryside, some brewers had begun to specialize and sell beer in communities. In towns, the process of specialization sped up, and independent breweries began to emerge. Much like monastic brewers, commercial breweries got more adept at making consistent beer (though they were also under the jurisdiction of the gruitrecht), grew larger, and began distributing beer around towns and local regions.

In the late seventh or early eighth century, people made the second transformational discovery that would change brewing: that hops could be used as a spice in beer. That is important, because people knew about hops long before anyone thought to put them in beer.

The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder famously mentioned them in Naturalis Historia around the year 78, though he recommended them for their tasty shoots (he called them, charmingly, “Gallic asparagus”). The first definitive mention of their addition to beer comes from 822, in a text by Abbot Adalhard from Corbie, France. The reference was a bit convoluted, but Adalhard was clearly referring to their use in beer. There remains a curious gap in the historical record. After Adalhard wrote about hops, they seem to have vanished from all documentation for another 300 years. They made a triumphant return in the twelfth century, but the intervening period is a black hole. During that time, brewing edged forward on its sleepy pace of growth. Farmhouse breweries were still the rule, but commercial breweries were becoming more common in the cities.

The discovery of hops was significant beyond making beer more delicious. As the Benedictine abbess Hildegard of Bingen noted, they act as a preservative, and this had two important effects. Hops allowed breweries to do more with their recipes, like making stronger beer (without hops, strong beer would turn to vinegar before it was done conditioning). More important, beer that could survive for more than a few days had the capacity to travel. Until the discovery of hops, beer was rooted firmly to the region where it was brewed. After hops, beers were moving across the continent, influencing distant brewers and the beers they made. Not that the process happened overnight—it didn’t. People didn’t immediately take to the plant’s unfamiliar, bitter flavor, and it took centuries for hops to become a standard ingredient. The use of hops was a revolutionary step in fighting infection and spoilage, though, and once hopped beer entered a region, it never left. In the eleventh century, almost no beer was made with hops; a thousand years later, almost no beer is made without them. ■

Hildegard of Bingen, Hop Mama. The two names commonly associated with hops are Pliny the Elder, credited with their discovery, and Hildegard of Bingen, credited as the first person to mention their use in beer. Pliny’s status complicates the narrative. It’s not even clear he was talking about hops when he identified the plant lupus salictarius—“wolf of the willows”—and if so, that he was really the first to mention them. Hildegard’s status is more straightforward. The abbess of St. Rupertsberg, near Bingen, was a mystic famous enough to remain the subject of modern scholarly interest, and an unlikely candidate for brewing saint. Yet she did in fact write about hops in her classic text on the science of the natural world Physica Sacra (an English translation is still in print), both in reference to brewing and with the knowledge that they “keep some putrefaction” from drinks (presumably beer). Of course, while this is all well and good, she was scooped by Adalhard, who mentioned hops in his texts more than 300 years before Hildegard wrote her Physica.

HOPS WOULD ULTIMATELY PROVE to be the killer app that transformed beer into a commercial juggernaut. The first success came around 1200 CE from Bremen (located in what is now northwest Germany), a member of the Hanseatic League of trading cities. Just a short boat ride down the Weser River from the North Sea, Bremen was able to take advantage of the preservative quality of hops and begin export. Ideally situated to ship beer across northern Europe, Bremen’s product went to Holland, the Baltic countries, and Scandinavia—and became the world’s first international beer. Hamburg competed with and eventually surpassed its Hanseatic partner in the 1300s.

Once other brewers saw how well Bremen beer kept, it wasn’t long before they began using hops, too. In relative terms, the transition was quick—though it still took decades. Government control of gruit and local tastes were part of the problem, but breweries also weren’t sure how to use the new herb and the German breweries were very happy to keep the method to themselves. England was the last country to adopt hops and one of the most resistant (some local officials even banned its use in ale), but by the early 1700s hops had conquered Great Britain, too. Gruit’s day had passed.

Were Gruit Beers Boiled? Beer was not considered a subject worthy of much scholarship in the Dark Ages, and there’s very little information about how it was made back then. One intriguing question is whether brewers even bothered to boil wort before the discovery of hops. Why would they? In order to release their bacteria-inhibiting goodness, hops need to be boiled, but boiling isn’t necessary to make fermentable wort. So why would early breweries spend the time and money to secure the wood for an unnecessary period of boiling? Even if they did bring wort to a boil to extract more flavor from the gruit, there wouldn’t have been any reason to leave it boiling very long.

Once hopped beer opened up distant markets, commercial brewing hit the big time. Larger German breweries were making more than a thousand barrels a year in the 1300s, twice that for the most successful producers. They made different styles of beer for different markets and sent out ships full of nothing but beer. Brewing had become big business, and brewers had become powerful men. With larger systems able to take advantage of efficiencies in production, bigger breweries could make beer more cheaply than smaller ones. These behemoths were able to influence the government, affect taxes (to their benefit), and with their size advantage, spark worries about consolidation. It might seem like a contemporary fear to worry about the power of huge breweries, but even then small brewers of the day were already raising warning flares. In time, beer’s success had even pushed the line of traditional wine-drinking Europe south as it established itself in Flanders and Southern Germany, causing all the more worry and anxiety.

By the end of the Middle Ages, beer had become quite a different substance from the one brewed at the beginning. Before the discovery of hops, beer was weak and sweet, and spoiled quickly. Spices helped round the flavor, but they didn’t exactly balance it in the way hops, with their unique spicy bitterness, could. Once brewers mastered hops, they were making stronger, more consistent beer that lasted longer without spoiling. But it also had a totally different character; it was no longer defined by sweetness. There was still enormous variation in local styles from place to place, but the nature of beer had been changed forever. Hops had become an intrinsic flavor that defined beer. ■

DESPITE THE RELATIVELY sprightly adoption of hops, the pace of evolution was pretty slow in absolute terms over the next few hundred years. There were the Dark Ages to slog through, the Crusades, endless wars, and plagues. But things were about to change. Between 1700 and the late 1800s, a great period of innovation occurred that transformed beer from a rustic, handmade beverage to a chemically stable, laboratory-pure industrial product. It took several hundred years for the hop revolution to fully flower, but industrialization happened in a breathtaking period that was just eleven decades long.

Beginning in the early eighteenth century, the British picked up where the Hanseatic League had left off and became the world’s great beer exporter. Breweries were making strong, heavily hopped beer called Burton that would survive years in casks and was well suited for long journeys across oceans. Porters followed—again, massive, heavy beers designed to last over long periods. The shipping network that sustained the British Empire transported beer all around the world—to Asia, Russia, Australia, and North America.

As the export market grew, so did the London and Burton breweries that supplied it. A big brewery in the 1300s made 2,000 barrels a year. By the mid-1700s, some breweries in London were making more than 50,000 barrels—and that was before the steam engine revolutionized the industry. The British enjoyed such success and renown because they were far ahead of other countries in technical innovation. They were the first to adopt thermometers, hydrometers, steam power, and refrigeration. In each case, these were innovations to the brewing method, and the result was more consistent, stable beer—and that, in turn, led to bigger breweries with greater reach. It gave the British a huge advantage in what was becoming a global market. Porter became an international phenomenon and was the world’s first truly modern beer. After porters, pale beers took hold and, like porters, they began to penetrate foreign markets and influence brewers elsewhere.

A copper grant at Rochefort. Grants allowed brewers to monitor wort clarity and control flow rate, and helped relieve vacuums from developing during lautering. Outside the Czech Republic, few modern breweries still use grants.

The Technological Revolution. The eleven decades between the adoption of the thermometer in the 1760s and refrigeration in the 1870s marked a period of staggering innovation in brewing technology—far surpassing all the advances made in the 8,000 years before. By the end of the period, brewing had become a modern industry, one improved upon in only small increments in the time since. Following is a list of the key inventions and discoveries and how they altered brewing.

■ THERMOMETER, circa 1760 (in breweries). Before the thermometer, breweries had no way of consistently reaching the same mash temperature batch after batch and could only gauge liquor temperatures with their bare hands or by assessing the amount of steam. The difference in a few degrees was the difference between a well-made beer and a failure.

■ HYDROMETER, circa 1780. The hydrometer allowed a brewer to determine the amount of dissolved sugar in solution, in both wort and finished beer. As a tool, it gave breweries a way of gauging their efficiency and improving their techniques. But it also changed the way breweries made beer. For example, the hydrometer revealed to London breweries how poor brown malt was in the porter-making process and led to the use of pale malts in the grist to improve mashing and fermentation.

■ STEAM POWER, circa 1785 (in breweries). Before the Industrial Revolution, breweries had to move water, grain, and barrels around with human- or horsepower alone. Brewers originally adopted steam power as a cost-saving measure, but soon realized that it also allowed them to produce far greater quantities of beer annually. For the first time, breweries were no longer limited to the beer they could sell locally. Industrial-scale breweries churned out porter that traveled around the world, creating an international market. Styles were no longer fixed in place.

■ ATTEMPERATION, circa 1800. Throughout brewing history, the summer heat was deadly to cooling and fermenting beer. In Britain, breweries learned that they could “attemperate” (lower the temperature of) wort with cool water. They ran hot wort through small pipes embedded inside larger pipes filled with cold water to bring it down to fermentation temperature in a matter of minutes and to pitch (or add) yeast quickly after boiling.

■ SPARGING, circa 1780s to 1850s. At the end of the mash, brewers sprinkle water on the grain bed to flush the wort and rinse the malt—the modern practice of sparging. Until the mid-nineteenth century, breweries conducted several mashes, drawing off successively weaker worts from the same grain bed. It was a laborious, time-consuming process, one much streamlined with the introduction of sparging.

■ PASTEUR’S TREATISE ON YEAST, 1857. Although brewers had for centuries understood the mechanism of yeast, prior to Pasteur’s work they didn’t understand why beer went sour. Not only did he clarify how beer was fermented, he pointed out why lagers typically had fewer problems with spoilage. The effect Pasteur had on brewing was stark and immediate. Lagers, a small minority of all beer prior to his publication, would come to dominate the global market within a few decades.

■ REFRIGERATION, 1870s. Heat has always been beer’s biggest foe. Attemperation helped breweries master it, and Pasteur explained why controlling it mattered. With the introduction of refrigeration, breweries got yet more control over heat, no longer having to rely exclusively on chill weather, cellars, and blocks of ice.

An early steam engine on display at the National Brewery Centre, Burton upon Trent, England

The next great international style, pilsner, was indeed a pale—but one brewed according to a different technological lineage. The method of lagering beer had been evolving in Bavaria since—well, no one seems to know for sure. Like the British effort to master temperature through attemperation, lagering—the process of fermenting beer cool and aging it in cool temperatures for weeks or months—gave Bavarian breweries a way to master souring organisms. It probably dates to the 1400s and developed only very slowly as breweries got more and more mastery over their fermentations. What brewers didn’t realize at the time was that they were domesticating yeast strains that would perform well in cooler environments.

Every region had slightly different brewing techniques, and lagering was, until the mid-nineteenth century, a quirk of Bohemia and Bavaria. Their beers were dark and popular only regionally. In 1842, however, brewer Josef Groll (a Bavarian) took advantage of lager technology to produce a sparkling, pale beer at the city brewery in Pilsen in Bohemia. Within a few short decades, pilsner would make all previous international styles look like pretenders. The timing was perfect for one beer style to become a standard. Technological advancements made mass production and distribution possible (via ship and newfangled rail lines), and refrigeration protected beer from spoilage and even the violence of heat on more delicate qualities like hop flavor and aroma.

Automobiles like this antique Palm Beer delivery truck were part of a wave of modernization in early 20th-century Belgian brewing.

But most of all, pilsner was a lager. This was significant because fifteen years after Groll’s first batch, Louis Pasteur published his studies on the science of fermentation, clarifying the role of yeast in the process. He explained how bad things happened to good beer, and he was a fan of lagering as a way of limiting the ravages of maleficent microorganisms.

This was the final of three ground-breaking discoveries that changed beer forever. Once breweries understood yeast, they quickly worked to produce pure strains. Around the turn of the twentieth century, N. Hjelte Claussen discovered a strain of wild yeast so common in British ales he named it for the country (Brettanomyces)—and yet within a very short time British breweries would eliminate wild bacteria and yeasts in their beers. Progress was slower in Belgium, where drinkers enjoyed tart beers, but by midcentury, soured ales would be a fading minority. Meanwhile, lager brewing spread worldwide, as Germans helped set up breweries across Asia and the Americas. Before breweries got a handle on pure yeast cultures, the character of beer had always been threatened by souring organisms—and most ales were at least tinged by acid sourness. Once breweries mastered wild fermentation, they eliminated it from all but a few precincts in northern Germany and Belgium. ■

WE HAVE COME 10,000 years or more from those lovely bowls of pre-Sumerian gruel-beer. Ninety-nine percent of history has been written. And yet, a survey of beer from the turn of the twentieth century would reveal a huge diversity of styles. Lager had begun its ascent, but it had barely touched Britain, Belgium, or France. Beer styles were still heavily conditioned by local traditions and preferences. That last one percent of history turned out to be eventful.

Consolidation began by the second half of the nineteenth century and never slowed down. London was home to the first industrial breweries in the eighteenth century, but steam power and technological advances allowed other countries to catch up. Once breweries became adept at producing large volumes of beer, they began snapping up market share. Big breweries could make beer more cheaply than inefficient village breweries, and their beer was usually better and more consistent. Even with population growth, there were only so many barrels of demand in the market, and it went increasingly to the more professional national breweries. Britain had more than 4,000 breweries at the turn of the century, a number reduced to 142 by the mid-1970s.

Cheap supermarket beers like this house-brand bitter from Sainsbury’s in the U.K. have done pubs and real ale no favors.

Had nothing else changed, the twentieth century would have been a time of continued consolidation as electrical grids came online and refrigerated trucks sailed along highways, giving ever bigger breweries the ability to make more and more beer. But things did change—and hugely.

The two events that changed modern history—the World Wars—also changed beer across Europe. The trenches of the First World War were cut across the heart of northern French and western Belgian brewing regions. The German war machine dismantled breweries, and most never recovered in France. During the Second World War, entire cities were turned to rubble—including their breweries. Physical destruction was only a part of the picture. To contend with years of war, European governments put restrictions on the amount of grain brewers could use—so traditional beers were often destroyed, too. The world left in the late 1940s included far fewer small family breweries, and traditional beer styles vanished by the score. ■

NORTH AMERICA FIRST made beer’s acquaintance 400 years ago. It arrived in the bellies of British ships, a scurvy-fighting tonic for the long journey across the Atlantic. For the colonists fond of their lovely brown tipples from home, that would remain the revered source of beer for decades. As the new arrivals soon learned, barley didn’t grow well in the Virginia or New England colonies. Virginians apparently made beer-ish beverages with corn, potatoes, persimmons, molasses, or whatever they could find that would ferment.

In between those two colonies, a different group had a bit better luck. Dutch immigrants settling in New Amsterdam (we now call it New York) built the first of many breweries on Manhattan in 1612. Breweries in Philadelphia and Baltimore followed later that century. Some of the breweries were successful, and the beer was apparently at least palatable—though everyone acknowledged that Britain’s ales remained far superior.

In the early decades of European residence in North America, the best beer was the kind that arrived by boat. The British shipped massive amounts to the colonists there—far more than they ever sent to India or the Baltics. Imports weren’t enough, though. Country brewers like George Washington made beer at home for the family and servants—a practice carried over from England. However, all of this was, pardon the pun, small beer: America was a rum and whiskey country.

The statistics are staggering. By 1763, New England alone housed 159 commercial distilleries; there were only 132 breweries in the entire country in 1810. By 1830, the U.S. had 14,000 distilleries; towns tolled a bell at 11:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m. marking “grog time”; and the per capita rate of consumption was nearly two bottles of liquor a week for every drinking-age adult. Beer either wasn’t very good or was an expensive import, and until later in the century it played only a minor role in the young nation’s hard-drinking ways.

That changed, gradually, with the influx of German immigrants in the 1840s. They brought with them a knowledge of German lagering techniques, and began opening breweries by the hundreds across the country. For the first time, beer’s role—and more specifically, lager’s role—in American life started to grow. A few ale breweries managed to survive, but German immigration effectively ended ale’s run in the U.S. Whatever vestiges did hang on were destroyed during the great social experiment of Prohibition. In Europe, brewing suffered in the early twentieth century thanks to wars; in the U.S., the suffering was self-inflicted. To get through Prohibition, breweries put out homebrew ingredients or made nonalcoholic malt-based products to compete with soft drinks. In 1900, there were nearly 2,000 breweries operating in the United States; in 1934, there were just 750. By then, lagers controlled the U.S. market and would eventually scrub all memory of ales from the American consciousness.

By the late 1960s, American brewing was no longer a craft—it was an industrial process conducted on a titanic scale. Breweries had learned efficiency, and the entire process was geared toward producing the largest quantity at the lowest price. Niche styles were inefficient. Small regional breweries were inefficient. The logic of industrial-scale brewing led to streamlining. Big companies bought up small breweries—many of which predated Prohibition—and converted their beers to the standard light lager.

The math was obvious: The remaining breweries were as big as battleships and turned out oceans of beer. Gigantism was the standard at every stage of production, from grain and hop deliveries to tun and tank size, from warehouse storage to fleets of delivery trucks. The bigger they got, the more efficient they got, all of which fueled consolidation in an ever-accelerating feedback loop. This efficiency was great on the production side. By the 1970s, consumption and sales were at an all-time high. In 1950, the largest five breweries controlled less than a quarter of the market; by 1980, they controlled three quarters and the total number of breweries had dwindled to fewer than a hundred.

For product offerings, the relentless homogenization was not so great. For one thing, beer drinkers had always been connected to their local breweries. They had always played up local imagery, local customs, even local pride. Resentment grew as the little guys got picked off, one after another. But more important, with each new acquisition the beer landscape got blander and more boring. Surveying the American scene at the time, writer Michael Jackson described the beery tableau this way: “They are pale lager beers vaguely of the pilsener style but lighter in body, notably lacking hop character, and generally bland in palate. They do not all taste exactly the same but the differences between them are often of minor consequence.”

George Washington’s “Small Beer” Recipe. As evidence that brewing was no easy task in colonial America, we have to look no further than the nation’s father, who had a house recipe for a substance he generously called “beer.” The text below; is taken verbatim; eccentric punctuation and capitalization are Washington’s.

TO MAKE SMALL BEER

Take a large Sifter full of Bran Hops to your Taste.—Boil these 3 hours. Then strain out 30 Gallons into a Cooler, put in 3 Gallons Molasses while the Beer is scalding hot or rather drain the molasses into the Cooler & strain the Beer on it while boiling Hot. Let this stand till it is little more than Blood warm. Then put in a quart of Yeast if the weather is very cold, cover it over with a Blanket & let it work in the Cooler 24 hours. Then put it into the Cask—leave the Bung open till it is almost done working—Bottle it that day Week it was Brewed.

Even if we render bran as “malt,” this looks like a bathtub version of beer—boozily fueled by lots of molasses. No wonder they liked the imported stuff better.

Fortunately, markets abhor a vacuum. The massive sales figures belied a growing discontent among a committed niche of beer drinkers. Over the course of the 1970s, a rebellion started to take shape. It included those who had traveled to Europe and tasted amazing, exotic beers and wished they were more available in the U.S. Many took up homebrewing. A few others wondered about trying to bring the tasty European beers back to the U.S. and sell them there. And a few especially romantic people tried to figure out how to start commercial breweries to make decent beers themselves.

In time, interest reached critical mass—enough to create an alternative market to the canned industrial product most Americans had come to know as beer. Homebrewers got organized and lobbied to have their hobby legalized. Fans of imported beer set up the first specialty importers or founded British-style pubs to stock those beers. Then, from 1976 to ’78, three key events helped the disparate pieces coalesce: Jack McAuliffe founded America’s first startup micro-brewery, New Albion; Michael Jackson published his groundbreaking World Guide to Beer; and Jimmy Carter signed a law that legalized homebrewing. It was a tipping point that led to the first wave of new brewery openings since Prohibition.

It is difficult to imagine the situation those first craft brewers confronted. These days, if you want to start a brewery, the blueprint is easy enough to follow. Breweries are a relatively safe investment, and banks are willing to lend money. Metal fabricators make beautiful new equipment to brewery specs—and the growth in craft brewing means it’s always possible to find a used system discarded by an expanding brewery. Educated, experienced brewers enter the market every year. Malt and hop companies work closely with craft breweries and will offer stock in tiny quantities. Most important, the market is substantial and growing, always thirsty for new beers. Small breweries are good business.

That was decidedly not the case in 1976. Craft breweries were tiny cogs trying to fit into the gears of a gigantic brewing industry. Banks wouldn’t loan them money and manufacturers didn’t make small-scale equipment. Malt companies dealt in volumes equal to train cars, not grain sacks. Distributors weren’t prepared to mess with the odd keg or case of beer. Early brewers had to cobble together brewhouses out of scavenged equipment, borrow money from family members, and beg distributors to take them on. Very often, they had to appeal to state legislatures to change laws so they could even operate in the first place.

It took a long time for “micro-brewing” to become a viable business model. The mortality rate for those first breweries was high. It had literally been generations since Americans had seen anything other than light lagers, so the craft brewers had to try to educate consumers as well as sell to them. By the mid-1990s, though, things finally started to change. Ales no longer seemed so alien to Americans, and millions were developing a taste for strong, flavorful beers. Craft brewing started growing, and has since posted annual growth every year for the past decade—even during the terrible economic downturn of 2008 to 2010. ■

THE TRENDS THAT led to a monoculture of style and a bland, lowest-common-denominator product were not unique to beer. Cuisine suffered as we learned to buy vegetables in cans and meats in the freezer aisle. There was a whiz-bang element to industrialization that wowed us, and the convenience was nice, too. They are no substitute for taste, though, and eventually, there was a countertrend in brewing.

It started in the United States and Britain, two of the countries most ravaged by consolidation. By the mid-1980s, both countries had doubled their brewery counts as a small army of new brewers entered the market to counter the blandification of beer with stronger, more characterful “craft beer.” The phenomenon spread to other brewing countries that were reaching their brewery diversity nadir in the 1990s. Those that fell the farthest rebounded the most impressively—Scandinavia and France boomed, and Italy, never known for its beer, has blossomed as a world leader in craft brewing. Established countries like Germany and Belgium have grown more slowly, but they have their own craft brewing movements. Canada, Spain, Brazil, New Zealand, and Japan are all getting in on the act. Added together, the number of breweries now has at least trebled from its lowest point.

Industrial-scale brewing is with us forever. Yet after just a few decades, some of those formerly small craft breweries have gotten quite big. The exciting prospect looking forward is that industrial beer may not always taste industrial. Large American breweries have been experimenting with “faux craft” beer for decades, and the Blue Moon and Shock Top lines are now among the biggest sellers in the craft segment. While this worries some discerning drinkers, they’re still a massive step up from Bud Light, the nation’s bestselling beer. This appears to be true across the globe, and some countries, like England, are hoping for an ale renaissance.

The market is not good at protecting monoculture. People like variety, and the long period of dominance by a single style was an aberration in beer’s 10,000-year history. Tasty, complex beer will be around as long as there are people willing to buy it—and there are a surprising number of them. While it’s true that craft beer makes up only a small segment of the total market, that doesn’t correlate to a small number of drinkers. In 2010, a market research company surveyed consumers and found that 59 percent of American beer drinkers drink craft-brewed beer at least occasionally. More important, half of those surveyed said they would drink even more craft beer if they knew more about it. As the market grows and expands, they will.

As a coda to beer’s history, let us finish where we started: evolution. Beer is never a settled matter, and beer styles never live forever. As craft brewing has revived interest in taste and variety, we’re seeing preferences diverge country to country. Americans have developed a love affair with hops, so that nearly any style can be reinterpreted as an IPA, including, strangely, “black IPA.” (Is there any other way to explain a black pale ale?) Britons, meanwhile, are still mad for a pint of session ale, though now that means more than just bitter. Germans are not about to forsake their accomplished lagers, but they are changing them. Italians have engineered hybrid beers meant to be drunk with good food, while France leans toward elegant, refined ales (at the same time keeping their eyes on the dinner table). And of course, they’re all influencing each other. Belgians are making hoppy beers, and Americans are making Belgian ales. The French are making cask ale, and the British are discovering craft lager. These trends get fed back into the cultural mill, shifting and mutating until they’ve created something yet again different and new. We can’t know what beer will taste like in fifty years except to say this: It won’t taste like it does now. ■

The Effect of Laws on Brewing. It would be difficult to say what affected the development of beer styles most, but local laws are surely in the conversation. The very first taxes involved the practice of government agents selling gruit, effectively a tax on ingredients—and this was a common category of law. The “German purity law” (Reinheitsgebot) is another, and the most famous. It was actually a Bavarian law—an important distinction because in the north, brewers made strange beers with spices, honey, and wheat. Indeed, it only applied to barley beers in Bavaria (the famous weizens were brewed under ducal exemption), and was also more a tax than a food-safety regulation.

Taxes have always been the main way government interacted with breweries, and how they levied their fees has had profound effects on what kinds of beer got made. In Britain, beer is taxed based on its alcohol content, resulting in various beers having appreciably different prices at the pub. It is little surprise that low-alcohol beers have long been favorites of both drinkers and brewers there. In Belgium, brewers were taxed on the size of their mash tuns—a bizarre system that resulted in small mash tuns no matter how much beer a brewery made. To get a lot of beer out a tiny tun requires ingenuity and elbow grease, and the old methods are still evident in the way lambics are made.

The absence of laws in an area was no less an influence on beers than their presence—especially when brewers were competing with their neighbors who had to adhere to more stringent regulations. Take the case of the small town of Hoegaarden, in Belgium. It fell outside the jurisdiction (or notice) of the taxmen of Liège, and as a consequence became a huge brewing center, exporting tens of thousands of barrels of tax-free beer in the sixteenth century.