Family-owned Drie Fonteinen blends an oude gueuze that combines bright lemon-rind notes with contrasting briny, umami flavors.

Lambics are rare, ancient Belgian beers made through a process of wild fermentation. Every other beer on Earth begins when a brewer pitches cultured yeast, a refinement developed centuries ago. Not lambics. Instead of pitching yeast, the brewery lets freshly boiled wort cool overnight, making it an all-you-can-eat buffet for wild yeasts and bacteria. They happily stream through the open windows, settle on the surface of the wort, and begin gorging. The following morning, the brewer puts the wort in casks where it will age for years, acting as an ecosystem for those now captive wild things.

The rule in other forms of Belgian brewing is no rules: Follow your bliss and make beers that conform to no standards or styles. Lambics are the exception; few beer styles have such a formal, almost ritual brewing process. Yet the beers are the opposite of mannered. Lambics and their variants—gueuze, kriek, framboise, and faro—are vibrant, improvisational beers. Those feral microorganisms are hard to manage, and the beers they make require discipline and consistency. The result is worth the effort—good lambics and especially gueuzes are the most complex beers in the world, and for many people, the most enjoyable. ■

Family-owned Drie Fonteinen blends an oude gueuze that combines bright lemon-rind notes with contrasting briny, umami flavors.

LAMBICS ARE sometimes described as beers unchanged from ancient times, made in the same manner as they were thousands of years ago. This isn’t strictly true. Twenty-first-century lambic breweries have the use of electricity, clean water, and the finest fruits of modern agriculture. Yet it’s not entirely wrong, either. Lambics are descendants of an ancient tradition in brewing, and they employ techniques that are at least hundreds of years old. The methods have been refined slightly, but they haven’t been abandoned.

Lambics emerged as a style in the area around Brussels—the only home they’ve ever known. The first mention comes from the early 1300s, but the tradition of farmhouse brewing from which they descend is poorly documented. Lambics are likely much older, or closely related to other much older beers. We know that they have remained largely unchanged for at least 450 years; a document from the town of Halle lists the proper grist ratio as 37 percent wheat, 63 percent barley—a ratio similar to today’s beers—and this ordinance refers to an earlier document from the year 1400. These beers are fixtures of the region, ingrained enough in daily life that they were immortalized by the Flemish master Pieter Bruegel the Elder in his paintings of Belgian peasants.

Spontaneous Fermentation. The word “spontaneous” has several meanings, but the one we’re interested in has the sense of “occurring without apparent external influence or cause.” Spontaneous fermentation happened when beer appeared to ferment without any action by the brewer. We now know there was a cause, but to brewers before Louis Pasteur’s great discovery in 1857, it sure didn’t look like it. They took wort straight from the kettle and cooled it in large pan-shaped vessels called cool ships (koelschip in Flemish). The brew day ended in the evening, and they just left the beer to sit and cool overnight. In the morning, the brewer put the beer in barrels and called it good. How it went from wort to beer was magical or mystical—in any case, spontaneous.

That’s still how lambics are made. Now we understand that there are actors involved—millions of them. They are the yeasts and bacteria that teem on the surface of cooling wort, hidden in plain sight. Modern breweries sometimes use fans to help the microorganisms find their way to the wort; others pump outside air through it. But never does a brewery add yeast. There’s a related process in which a brewery “pitches” yeast by relying on microorganisms resident in the wooden vessels to do the work—but this is not true spontaneous fermentation. The beasts that inoculate lambics must be free range. Spontaneous fermentation is the most radical kind of brewing because a brewery has no control over the most vital process in beer making. It is dangerous, but also sublime. And when the wrong characters come along instead? (Even for master lambic makers, wild yeasts can sometimes produce unpleasant flavors and aromas.) That’s why lambic makers blend their beer, to smooth out the rough edges. (For more on the mechanics and science of spontaneous fermentation, see About the Science, and Brewing Notes.)

Even at the low estimate, 700 years, they are one of the oldest styles left on Earth. In that period and earlier, spontaneous fermentation—making beer without pitching yeast—was the standard method for fermenting ale. In what are now Germany and the United Kingdom, breweries moved to pitching yeast as soon as they realized it improved their beer. (Like bakers working with starter, brewers took a pinch of the previous batch of beer to help the next one get going—though they didn’t know exactly what they were pitching at the time.) Belgians were far slower to abandon spontaneous fermentation. Even as late as the end of the nineteenth century, they were making beers using the method, and most Belgian breweries still used flat-cooling vessels rather than the wort chillers the technologically advanced English had been using for a century.

Cantillon’s Lou Pepe beers have a fruity taste that distinguishes them from the brewery’s other offerings.

If there is an explanation for why lambics survived in Belgium, it is the fidelity brewers have to traditional methods. Belgians love to tinker with recipes and ingredients and they don’t like to copy other beers. Where they are slow to change is technique. Even as German, Bohemian, and British breweries raced to adopt new technologies and dominate growing markets, Belgians stuck to their small-scale, handmade ways. In Hoegaarden, the precursor to witbier survived as a spontaneously fermented ale into the twentieth century. Leuven, the center of advancement in Belgian brewing, was home to another spontaneously fermented beer called dobbel gerst “made like lambic and faro.” Lambics survived because many old styles survived.

That doesn’t mean lambics didn’t change. The Belgian government passed a bizarre tax law in the nineteenth century that assessed a fee based on the size of a brewery’s mash tun. Tax laws are often strange, but this was an especially convoluted proxy for the volume of beer a brewery would produce. It gave breweries incentives to use tiny mash tuns no matter how much beer they sold. The result was a type of brewing unique to Belgium wherein breweries packed their small mash tuns with grain and then slowly mashed them over hours. Known as a “turbid mash,” this process became the standard still followed today by lambic breweries.

Faro is effectively extinct; it was once quite popular among the cafés of lambic country.

For centuries, straight lambic and especially faro were the main products of the lambic breweries. Faro, released green and sweetened with sugar, was a common table beer until recent decades, and could be found, served in pitchers, around Brussels. It has mostly died out. Gueuze, on the other hand, is a more recent innovation, dating to the mid-nineteenth century, when breweries first began to bottle lambic. This presentation wasn’t immediately popular, though; a hundred years ago, it accounted for less than 10 percent of lambic sales.

The world wars delivered their usual deleterious blow to lambic makers. In 1910, lambic breweries produced an astounding 1 million hectoliters (850,000 U.S. barrels). Those numbers crashed after the wars, as both German lagers and a debased version of lambic—young, artificially sweetened, and carbonated—began to displace the traditional product. Unlike faro, which preserved lambic’s rich character, these modern beverages were designed to capture the attention of the soda drinkers who were beginning to spurn old refreshments for something modern—and they were more like faintly tart sodas themselves than like lambics. By 1965, there were just twenty-seven lambic breweries and about twenty blenders left.

The lambic maker Frank Boon is one of the pivotal figures who helped rescue the style in the 1970s. Boon comes from a brewing family, and he recalls the changes lager brought when it finally penetrated the market. Small breweries abandoned local styles and “switched to cheaper and technically better beer.” Lambic makers didn’t help their cause, releasing good as well as subpar beer. “It’s like the old professor said: ‘These old lambic brewers, they sell gueuze like they sell pigs: Everybody wants the best meat, but you have to sell the whole pig.’ When customers complained that there was no head on the beer, [breweries] said it was proof that there were no additives in it. If it was cloudy, they said ‘See, it’s the proof that it’s unfiltered.’ If it was foamy, they waited until the winter to sell the beer.”

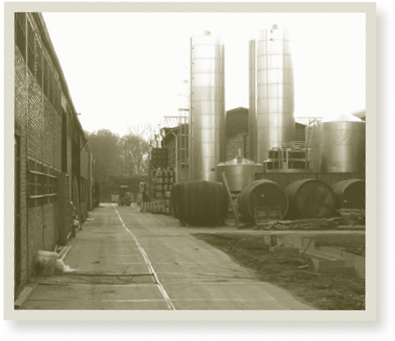

This nineteenth-century equipment may look like a steampunk throwback, but it’s state of the art in lambic brewing.

“Taste of Summer.” Historically speaking, lambic brewers may not have understood the mechanism of fermentation, but they understood what worked. And fermenting beer in the warm months wasn’t it. Writing in 1851, Georges Lacambre, the brewer who documented dozens of Belgian beers, described what happened if fermentation temperatures got too high. The phenomenon even had its own name: versoemer.

The result strongly affected the taste and the more or less nauseating odor is the true character of this kind of alteration. The smell is so characteristic that an experienced man can easily … recognize this kind of alteration simply [by] smelling beer that has received the slightest breach of versoemer or “taste of summer.”

In order to balance the cooling time and rate of wild inoculation, and avoid the dreaded versoemer, lambic breweries still only brew when nighttime temperatures approach freezing—October through April.

By 1970, the lambic maker Belle-Vue (now owned by A-B InBev) went on a buying spree, snapping up every lambic maker in Brussels except Cantillon. The company consolidated the production of traditional gueuze from the acquired breweries to just one site. Traditionalists like Frank Boon, Jean-Pierre Van Roy of Cantillon, and Armand Debelder of Drie Fonteinen refused to let the old styles die, though, and lambics have made a slow comeback since then. The greatest threat now is among companies that slap traditional fruit lambic names on treacly concoctions made with just tiny amounts of actual lambic. Finding a good kriek in Belgium has become hard work (though you can find nice examples by Drie Fonteinen and Oud Beersel on the export market), and the name is now associated with soda-sweet fruit beers. But the traditional breweries, still small by any reasonable standard (Boon, the giant, has only 8,500 barrels of oak-aging capacity—the size of a relatively small craft brewery in the U.S.), are flourishing in the now-tiny market. Lambic blenders, too, work with only small volumes, but they seem to be successful enough so that a new blender, Tilquin, has entered the market. ■

MOST BREWERY TOURS linger over the polished, tiled brewhouses, where the curves of the kettles gleam seductively. By the time you reach the fermenters, you’re fairly trotting alongside a brewer who barks out statistics measuring days and temperatures. When I visited Brouwerij Boon, the enigmatic owner, Frank Boon—a combination of the Cheshire Cat and Willy Wonka—marched me through the brewery double time so we could get to the warehouse where dozens of Econoline-sized oak vats rest like sleeping bears. Lambic is a product of time and wood—there is no other way to make it—and that’s where the action is.

Lambic brewers begin with a single recipe that becomes the base beer for all the other permutations falling under the lambic umbrella—gueuze, faro, kriek, and framboise. By tradition, lambics were made with pale barley and unmalted wheat, and that’s still true. In 1965, lambics achieved some measure of legal protection for their product as well. Lambic itself is not protected, but because it is the base of gueuze, which is, lambic traditionally adheres to the following rules, now recognized by the European Union:

■ Lambic must contain at least 30 percent unmalted wheat (40 percent was traditional).

■ Lambic must be spontaneously fermented, meaning no yeast has been added.

■ Hops must be aged at least one year (three is usual).

■ Gueuze must be refermented in the bottle.

■ Certain compositional elements must be measurable in a laboratory setting, including the presence of Brettanomyces, the absence of isoamyl acetate (a measure of aging), and the presence of certain other volatile acids.

■ Lambic must be aged at least one year in a wooden cask and gueuzes must include one-, two-, and three-year-old beer.

At birth, lambic is a cloudy wheat ale that has something in common with Bavarian weizens and witbiers. Saccharomyces cerevisiae—the rough country cousin of standard ale yeast—is the first of the wild yeasts to act on the beer; after a few days, the wort turns into a strange, fruity sludge. This isn’t lambic—not yet. Time allows an intricate waltz of the different microorganisms in the wort, each coming in at certain moments and then stepping back to make room for others. The beer won’t be finished for one to three years, though the subtle effects of age will continue to influence the beer for years after that.

Pronouncing “Gueuze.” There’s no single or correct way to pronounce “gueuze.” Lambic makers themselves pronounce it differently. “Gurz” or “Gurz-ah” seem to be the most common, but “Gooz” is also acceptable. The vowel sound is similar to “purse,” but flatter, as if you’re swallowing the word while you’re saying it.

At maturity (typically two years), lambic has exhausted its supply of sugars and is quite dry. Its unique character will be defined by countless factors, from the yeasts and bacteria that inoculated it during fermentation to the interactions of wood, oxygen, and wort that happen inside the cask. Remarkably, a batch of the same lambic spread over multiple casks will evolve differently as the ecosystems within the casks give the contents individual personalities. Some lambic is balanced enough to be packaged and sold straight (Cantillon Grand Cru Broucsella, a three-year-old straight lambic, is the best-known example) or on draft around Brussels. But most lambics will not emerge in perfect balance and will be blended into harmony in gueuze.

An exotic presentation for an exotic beer

One could be forgiven for imagining gueuze (sometimes rendered “geuze”) is an inferior version of straight lambic—as blended whisky is to single malt Scotch. The reverse is true. Straight lambics can have depth and character, but they can never approach the symphonic complexity and accomplishment of a well-made gueuze.

Unlike straight lambics, gueuzes are hugely effervescent and tartly refreshing—Belgians like to compare them to sparkling wines. They boil from a bottle as if propelled by heat and pile up gorgeous, thick heads. (In a Belgian café, the server will deliver a bottle of gueuze to your table from the restfulness of a little wicker basket; once he decants the golden bubbly into a rustic, pleated tumbler, he lays the bottle, prone but neck raised, in the basket on your table.) The best examples are at once deeply complex but absolutely approachable, containing within their unassuming appearances everything from the zest of citrus rind to white wine grapes, from earthiness to subtle hints of funkiness. They are tart beers, but those words belie the true nature of gueuzes, which while tart are not vinegar-sour and while beer have more in common with wines. They are like nothing else in the world.

Part of this is age: Gueuze is a blend of vintages. As lambic ages, it expresses different qualities at different moments. First comes the primary alcohol fermentation of regular Saccharomyces, which may last a few months. Next, lactic acid fermentation begins, turning the beer very sour, a process that consumes another few months’ time. Finally, another stage of alcohol fermentation begins, as the Brettanomyces becomes active. (Actually, Brett is working the whole time; it’s just so slow it hasn’t built to sufficient numbers to begin producing the compounds that will affect the lambic’s flavor.) That Brettanomyces will continue to plug along for years, munching sugars and adding flavor and aroma compounds. By mixing different vintages, lambic makers and blenders are taking flavor snapshots from different times and merging them into something wholly new.

“I first taste my old lambic. If I have a mellow lambic with some soft beer, I can work with two- and one-year-old with mild character. If I have an old beer with character, I have to find other types of beer. Each blend is different. From time to time the gueuze is too woody—a woody taste coming from old barrels. Once, when I made the blend I thought the taste would decrease with carbonation. I was wrong! The beer is never the same. Never. You never know what you will discover. That’s why lambic is so fun.”

—JEAN VAN ROY (SON OF JEAN-PIERRE), BRASSERIE CANTILLON

Blending has other advantages. Brewers and blenders can never achieve true batch-by-batch consistency (nor would they wish to), but they do want their products to be recognizable. Blending gives Cantillon its lemony character, Boon its smoothness, and Drie Fonteinen its surprising briny center. Blending allows breweries to select single notes from different batches of lambic to construct layers of flavor not possible in single beers. Finally—and functionally—it allows breweries to work with lambics that have gotten too funky, too tart, or that lack the character to be served on their own.

Belgian Blenders. Blenders (steker in Flemish) are unique in the world of beer making—and generally misunderstood. They do everything traditional lambic makers do except produce the initial inoculated wort. Instead, they buy lots of inoculated wort from the lambic breweries—largely from Frank Boon, who supplies about 60 percent of the total. From there, blenders age the beer in their own cellars, either blending it from their own barrels later, selling it straight from their barrels, or adding fruit for kriek, framboise, and other fruit lambics. Labels don’t always make the distinction between blender and brewer obvious, nor should they. The hard work and the art are in the aging and blending, and the beers that come from blenders such as De Cam, Hanssens, Oud Beersel, and the new blender Tilquin are every bit the equal of the breweries from which they receive their wort. Indeed, the blenders have an additional advantage over the breweries: When they blend their gueuze, they can draw on the production and distinctive characteristics of multiple breweries.

If people outside of Belgium have heard of lambics, it’s usually by the name of their fruity incarnations: kriek (cherry, pronounced creek) and framboise (raspberry, pronounced frahm-Bwahz). These are the most famous and common varieties, but breweries infuse young lambic with fruit for six months to make cassis (black currant), strawberry, peach, grape, apple, and blueberry lambics.

The effect of fruit on lambic is surprising—its sugars do not sweeten the beer, yet its flavors and aromas are captured seemingly at the moment it was picked. Yeasts have months to consume all fermentable matter, and they leave behind the fruit’s essence. In fact, sour beers do a far better job of preserving and presenting that essence than regular beer. Lambics lack the heaviness and malt flavors of other beers; theirs is an almost distillate-like solution.

The Église Royale Sainte-Marie, a parish church in the Brussels neighborhood of Schaerbeek, which was once a small village famous for cherries used in kriek.

KRIEK

Beginning at least 400 years ago, villagers near Brussels harvested native sour cherries and delivered them to the city on donkeys. Schaerbeek, nicknamed “the village of donkeys,” was the center of cherry cultivation and gave its name to the fruit originally synonymous with kriek. That village is now a neighborhood in Brussels, which gobbled up the fruit trees as it grew and spread out over the countryside. Now most cherries used in kriek lambic come from Poland, which has a similar variety. Nevertheless, among fruit lambics—and Belgian fruit beers generally—kriek is still king.

Cherry’s triumph has less to do with regional history or local preference than the way the fruit and beer harmonize. Cherries have a rich flavor that comes from sugar, acid, and the tannins of the pits (which are always used). And color! No other fruit can stain a beer so intensely, and unlike other fruits, cherry’s color doesn’t fade. The best oude krieks (literally “old krieks”—referring to those made the old-fashioned way) are lush beers, scented with fruit so fresh it tastes like it was picked that day; they are tart but rounded, with woody, spicy, or even cinnamon qualities.

Unfortunately, not all krieks are made the same. In the past twenty years, as sugary drinks became increasingly popular, makers began to debase krieks, diluting them with regular beer, filtering them, adding sweeteners and sugars, and/or using juice or syrups to add flavor. Even some traditional lambic makers followed suit, trying to keep demand and production up. Not only do these beers threaten the far more expensive and temperamental true lambics, but they’re absolutely terrible—like limply carbonated cough syrup. One rule that will guide you well in your exploration of authentic lambics is to buy those with “oude” in the label—those are made the traditional way. In Belgium, kriek lambic or kriekenlambik sometimes appears on draft—it’s also the authentic, straight-from-the-brewery good stuff.

FRAMBOISE

Almost as famous as kriek—and possibly older—is raspberry lambic. It is now rarer, however, in part because raspberries aren’t as abundant, and in part because the fruit is harder to work with. Framboise is a lighter pink than kriek, and its color fades over time. It is more acidic and drier than kriek, but it also has lighter, springier character.

Look for the Oude. In Flemish, oude is “old,” and in lambic, old is good. Even though lambics claim only a minuscule share of the Belgian market, the words “kriek” and “gueuze” still have cultural currency—enough that these styles of beer have been repurposed as easy-drinkers, competing with mass-market brands. For decades, lambic makers have tried to protect their product in the courts, and they’ve managed to carve out some protection for their authentic product. The key is the word “oude.” Beers with this designation are made with the requisite unmalted wheat, and they are spontaneously fermented and aged in casks. They are now protected by the EU as “Traditional Specialty Guaranteed.” Consider anything else suspect.

Any type of fruit may be used to flavor a lambic, and brewers and blenders have experimented with a wide range of them. Lindemans is most associated with the use of fruit in their beers—peaches, apple, cassis—but these aren’t authentic lambics. They start out as proper lambics, but after six to eight months, the lambics are mixed with sugar and fruit syrup and then bottled without a secondary fermentation. The beers successfully hide all evidence that lambics were in any way involved in their manufacture.

Cantillon, always one of the most experimental lambic makers, has used a number of different fruits, but in the service of authentic lambic. The Van Roys make lambics with grapes (Vigneronne, St Lamvinus), apricots (Fou’ Foune), and blueberries (Blåbær Lambik, sold only in Copenhagen) in addition to making kriek and framboise. One other beer worth highlighting is Oudbeitje, a strawberry lambic from the blender Hanssens. The color from the berries is long gone by the time you pour out the beer, and the character tends toward the musty/funky quadrant of lambics, yet it is one of the most interesting, unusual fruit varieties made.

Lindemans is perhaps the best-known fruit lambic producer—even though their “lambics” take liberties with the style.

In the old triumvirate of lambic types, fruit lambics and gueuze were joined by faro (pronounced Fah-row). Until the First World War, faro was the most popular variety of lambic, sold in cafés around Brussels and Pajottenland. Brewed at a lower gravity than its tart cousins, it was sweetened in the cask before serving, often at the café, to stimulate some carbonation—not unlike English cask ale. Today faro is mostly extinct; where it is made, it is usually bottled. It’s higher in alcohol now, and a strange orphan that satisfies neither the preference for sugary beers that the modern “kriek” offers nor the growing appreciation for traditional, tart lambics.

Lambic makers and blenders sometimes experiment with slightly off-beat products as well. Cantillon has an all-barley lambic called Iris made with regular hops (as opposed to the aged ones typically used). Mort Subite releases very young lambic in a product called Blanche that may well approximate turn-of-the-twentieth-century witbier, a spontaneously fermented ale that was a very close cousin to lambic.

One of the most interesting phenomena in the world of tart Belgian beer is the spread of traditional lambic methods to other breweries in the country (and indeed throughout the globe). These lambic-like breweries don’t necessarily compete on all the points of tradition, yet they don’t skip the important stages: spontaneous fermentation and wood-barrel aging. The West Flanders brewery Bockor spent nearly a hundred years making the oud bruin of the region—another tart beer discussed later—but in 1970 began experimenting with spontaneous fermentation. The beer is aged eighteen months in oak, but is generally blended with nonlambic beer and syrups. The West Flanders brewery Van Honsebrouck, the makers of the Kasteel line, also makes beers from spontaneously fermented stocks, with similar results.

More interestingly, the craft brewery De Ranke (also in West Flanders) experiments with two blends, half of which they brew themselves. Kriek De Ranke and Cuvée De Ranke are made from a tart Flemish brown ale that the brewery produces. They blend it with Girardin lambic from the traditional maker near Brussels—as well as with cherries in the kriek. ■

Faro is still served from a traditional earthenware pitcher at Brasserie Cantillon.

THERE’S AN OLD episode of The Simpsons where Homer’s stooped, ancient boss, Montgomery Burns, visits the doctor and learns that he has nearly every disease known to man, but he remains in good health because they all cancel each other out. Lambics are something like that. They are afflicted by Acetobacter, Enterobacter, Pediococcus, Lactobacillus, and Brettanomyces and other oxidative yeasts; scientists have identified over two hundred organisms at work in lambics. Any of these have the capacity to ruin a beer, yet throw them together under the right circumstances and they all keep each other in a kind of astonishing harmony.

We’ll talk about the life cycle of a lambic in a moment, but first a word on acids and esters. When the various microorganisms begin digesting sugars, they produce alcohol—but also acids, and from those acids come related esters. Acids are responsible for the sour flavors and the funky or pungent ones, while esters create fruity aromas and flavors. This is why lambics are so complex—there are dozens of compounds at work. Acetic and lactic acids are two of the compounds that make lambic tart; the esters derived from them are ethyl acetate (which tastes like apple at low levels, like solvent at higher levels) and ethyl lactate (which ranges from fruity to buttery). When we encounter funky notes in lambic, we’re picking up these strange compounds. The trick in lambic brewing is finding a balance and concord among them. Fortunately, nature takes care of most of this.

From the moment the sterile, sticky wort leaves the brew kettle and enters the cool ship, a brewer is at the mercy of the tiny beasts of the air to turn it into lambic. Those microorganisms work in waves, each doing its part to transform the beer. The quickest to act are two rough characters known as Enterobacter and Kloeckera apiculata. The latter may help break down proteins for later stages of fermentation, but Enterobacter is dangerously noxious. A source of food spoilage, it causes rotten, vegetal, and fecal-smelling compounds and is an acetic acid (vinegar) engine.

After a few days, the population of Saccharamyces cerevisiae cells—regular ale yeast—have multiplied enough to begin alcohol fermentation, overwhelming K. apiculata. A couple months down the road, Enterobacter will make the environment toxic to itself by lowering the pH. Although Enterobacter introduces unpalatable compounds into the beer, it contributes acids critical to making the tartness that characterize lambic. Those off-flavors can overwhelm a beer, but in order to do so they must survive further rounds of chemical changes.

Once primary alcohol fermentation winds down, lactic fermentation kicks in, beginning roughly four months into the lambic’s life. While Lactobacillus is present in lambics, it is kept in check by hop acids; instead, Pediococcus will be the source of lactic acid in lambic. This stage lasts three to six months. (The variation in times is related primarily to temperature.) Lactic fermentation produces what lambic brewers call the “sick” stage—the beer takes on an unsightly oily texture and builds long, mucousy strands. A lambic must be brewed in cold weather so the wild yeasts aren’t too wild. By the time the cold weather returns again, the sick stage ends and the lactic acid is reabsorbed into the beer. This is the earliest stage at which lambic can be called “complete”—but there’s one critical stage left.

The final actor in this drama is the great Brettanomyces, the wild yeast that has been very slowly building up its population over the months. In the final months, Brett will begin work on the remaining sugars (about 20 percent) and conduct a second alcohol fermentation. During this phase, which can last well over a year, Brett will add its own character and give the beer the final array of aromatic and flavor compounds; the beer may also form a pellicle—another unsightly growth that looks like mold on the surface.

The remarkable thing about lambics is that at the end of this protracted process, they don’t taste horrible. Throughout their life cycles, the different microorganisms interact differently with the environment—the ambient temperature in the casks, the amount of oxygen that enters through the wooden staves—and these factors produce variations in the levels and amounts of compounds. Most casks won’t contain spectacular stand-alone beer, but they will have the qualities that, when blended, will together make spectacular beer. After two years of biochemical change, the various wild yeasts and bacteria will have finally played their part in the theatrics. Lambic will continue to change with the effect of oxygen over the next year, but after two, it has become a stable beer. ■

WE’VE TALKED a lot about what happens after the wort reaches the cool ship, but what happens beforehand is nearly as strange and unorthodox. Brewers begin with a mixed grist of at least 30 percent unmalted wheat and conduct a laborious mashing regimen to create wort full of enough proteins and starches to give the various microorganisms something to chew on over the next two years. The “turbid mash” begins with a cool infusion of water and then the brewer raises the temperature by removing, heating, and adding wort back in and so on over the course of hours. The idea is to produce a cloudy wort that will provide fewer active nutrients during the dangerous early stages of fermentation, but more dextrins and starches for the yeast to munch on in the later stages.

The exhausting mash is only the first half of the marathon; the boil comes next, an hours-long ordeal that recalls methods described in nineteenth-century texts. Periods vary from four to six hours, and the theory holds that beyond reducing the volume to the target gravity, a long boil helps coagulate the raw wheat protein and pulls out the maximum level of antibacterial agents from the aged hops. (Lambic makers use hops at least a year old but generally three. From these they extract little bitterness, which would get harsh in the long boils, but get those antibacterial compounds critical in inhibiting the excesses of wild fermentation.)

Climate Change and Lambic Production. Ideally, a lambic brewer likes the mercury to drop to freezing overnight, a temperature that will result in wort reaching 64° to 68°F by morning. This protects the wort from being infected by dangerous wild yeasts and bacteria. Fifty years ago, lambic breweries could begin brewing in mid-October and continue through the end of April. Now, it takes longer for adequately cold temperatures to arrive in Belgium. Looking at his grandfather’s logs, Cantillon’s Jean Van Roy has seen the average number of potential brewing days drop by a month—and counting.

From there, the process proceeds through the cooling, aging, and blending stages described already. ■

ONE OF THE criteria for producing authentic lambic is that it be made in the small region around Brussels. There’s no law protecting this rule, and until a decade ago the question of transgression seemed theoretical at best. But what if a brewery did follow every guideline, particularly the requirement to spontaneously ferment the beer in a cool ship, except that it was brewed outside Brussels—what should that beer be called?

Upland Brewing in Indiana includes a variety of fruited lambic-style beers in their sour ale program.

The question is no longer theoretical. Several American and Italian breweries have put their toes in the turbid mash. Out of deference to the Belgian breweries they admire, they don’t call their beer lambic—they say “lambic-style” or “spontaneously fermented” or other similar language. Yet some of it meets every criteria except location. Sour beers have become a serious niche in both countries—not huge in absolute terms, but popular enough to support a growing segment in those countries. To avoid confusion with the classic production of the lambic region, these beers are described in a subsequent chapter. Make no mistake, though: The taste for lambics has reached other countries and now there’s not enough of it to go around. Belgian breweries and blenders must turn away foreign requests. As a result, breweries elsewhere are learning the old ways and making spontaneously fermented beers themselves. ■

ONLY EIGHT LAMBIC brewers still exist: Boon, Cantillon, De Troch, Girardin, Lindemans, Mort Subite, Timmermans, and Drie Fonteinen. The last suspended brewing in 2009 after a brewery accident and spent the next three years blending lambics. The world was fortunate when Armand Debelder put together funds sufficient to buy new equipment in 2012, so Drie Fonteinen is a brewer again. In addition, there are another four blenders: De Cam, Hanssens, Oud Beersel, and Tilquin. The volume of authentic lambic that these breweries and blenders produce is small enough that very little is available to export markets.

All of the authentic lambic and gueuze produced by these breweries is exceptional, but there are some imposters lurking. De Troch makes the “Chapeau” line of fruit lambics, all of which are syrup-sweetened and inauthentic. Lindemans fruit lambics, the most widely distributed, are also syrupy and should be avoided; however, the brewery makes an authentic gueuze called Cuvée René as well as an oude kriek that are wholly traditional. Timmermans, though sweetened, retains some sharpness.

The very best products come from Boon, Cantillon, Drie Fonteinen, and Girardin, and all the brands made by these brewers are reliably authentic and—more important—extraordinarily good. Because the process includes variability, the vintages are never exactly the same, so I haven’t included specific reviews here; they only serve to capture a snapshot of a point in time. I highly recommended them all.

LAMBIC BREWING IS BY DESIGN AN ANCIENT PRACTICE, BUT EVEN AMONG LAMBIC BREWERIES, CANTILLON IS THE MOST IMPERVIOUS TO TIME. THE EQUIPMENT, THE BREWERY, THE METHODS—EVERYTHING COULD HAVE COME STRAIGHT FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY. CANTILLON HAS A MUSEUM AT THE BREWERY AS WELL, BUT IF YOU VISIT, YOU’LL FIND THAT THIS IS A BIT REDUNDANT: CANTILLON IS A MUSEUM.

I scheduled my visit to coincide with a day brewer Jean Van Roy would be brewing—a practice limited by the cramped cask space in what is now a nondescript urban neighborhood in Brussels. Cantillon’s equipment is steampunk old, and very hands-on. When I arrived, Van Roy was elbow deep in a vessel that looked a bit like a hop back, shoveling out material that had been reduced to mulch.

Van Roy has a disarmingly democratic approach to visitors: mon brasserie, votre brasserie. He told me just to go wander around if I wanted to see the rest of the place—he had no time to offer a tour. Cantillon has the feel of a warehouse, with anemic lighting and tight spaces. I went up wooden stairs to the kettle room and up another flight to where the casks rest in shadows. The cool ship hovers on a loft above the cask room, where open windows let in the Brussels air. It’s up one last flight of stairs, walled in by white-painted brick, and accessed by a rough-hewn door on a landing. On a chilly day, the steaming wort creates clouds of ethereal mist that waft through the rafters, and I spent probably fifteen minutes communing with this scene. For an American lambic fanatic, this was ground zero for one of the most remarkable events in brewing.

In the romantic story of lambic brewing, you always hear about the pastoral Senne Valley just south of Brussels, laden with fruit trees and populated by farmers smilingly working the fields. My mind conjured a kind of rural preserve where the wild yeasts were pristine and untroubled by modern life. In the case of Cantillon, I was all wrong. The brewery is in the middle of a gritty urban tableau and those wild yeasts have definitely been slumming with some streetwise elements.

But the yeasts outside the brewery are only part of the equation. Cantillon, the museum, is rife with life. Nothing is disturbed, lest the inner ecosystem be thrown out of balance. “You have to create your own atmosphere in the building,” says Van Roy. I had heard tales of even cobwebs left intact—and indeed, on the old casks and beams where the lambic aged, there they were.

After his brew day, Van Roy was ready for a beer. He disappeared and returned with a small pitcher of the kind that faro was once regularly served in. Again he disappeared, and this time returned with a bottle of five-year-old gueuze and one of the traditional wicker serving baskets. I asked him about his process, and he approached the subject with the imprecision of a theologian. “When we taste such a lambic we are so proud—for me, but also for the product itself. No one, no brewers on the earth can have the same rapport, the same feeling with his beer. In French we have a sentence. We say, Tout est dans tout. If I translate it: ‘Everything is in everything.’ In this brewery, everything is playing a role in the final product. Everything.” He continued: “I know my beer. I feel my product. The beer is alive. I really have contact with the beer. I feel, I smell what the beer will accept or not.” Van Roy has a monkish manner to go with his theological descriptions—eloquent when he is finally coaxed into speech, and firm in his convictions.

Cantillon brewer Jean Van Roy has an almost spiritual approach to the art of making lambic.

Cantillon is perhaps the most admired lambic brewery in the world, not just for its beer, but because the Van Roys—Jean and his father, Jean-Pierre—have been at the leading edge of preserving the art. It does not hurt that Jean is generous and welcoming and has helped breweries in the U.S. and Italy experiment with spontaneous fermentation. But mainly, he is the face of lambic to the world, and when the world thinks of a lambic brewery, it envisions Cantillon.

Just a few miles south of that famous brewery is the small town of Lembeek, where lambic was born. It is also the home of Brouwerij Boon, which I visited the day after my trip to Cantillon. It was a fascinating contrast of styles. The brewer, Frank Boon, is emphatically not a museum brewer; in fact, he’s one of the most microbiologically sophisticated beer makers I encountered in Europe. He currently has a traditional old brewery, but is in the process of upgrading everything—well, almost everything. He will install the world’s first modern lambic brewhouse, purpose-built to accommodate the rigors of turbid mashing, but designed to create absolutely consistent worts batch after batch. The traditional part of the process—cool ship, wood aging, and blending—will continue in the centuries-old traditional method.

Brouwerij Boon is the last of the lambic-makers still located in Lembeek.

Frank Boon pulling a sample of two-year-old lambic

Casks bound for blenders bear the brewery’s mark.

The Boon brewery is located in sight of the famous Senne River, but again my expectations were thwarted. The river is tiny—a stream one could ford on foot. It’s a much more rural location than Cantillon’s, but it’s still just thirteen miles from Brussels’s Grand Place—located, essentially, in what Americans would call a suburb. Boon told me that valleys were historically important for lambic brewers—and dangerous for regular breweries, which prefer high ground. Valleys create pools of still air, and microorganisms collect there. River valleys are even better, because the fog and humidity help keep the wild buggies from drifting away. Even though the Boon brewery is only a few miles from Cantillon, the wild yeasts are definitely different there—as anyone who’s tasted beer from the two can readily attest.

Another area where Boon and Cantillon differ is their casks. Cantillon uses wine barrels, but Boon uses vats—twenty to forty times bigger than wine barrels. This has a substantial effect on the beer. The percentage of beer exposed to wood is greater in a smaller barrel, which affects the density of resident microorganisms and the amount of air that permeates the staves. I mentioned to Boon that I’ve seen some published analyses of which yeasts become active in the life cycle of lambic and asked if his followed the same pattern. Boon has been working with a university microbiologist to learn more about his yeasts—likely the most far-reaching studies into the biology of lambic ever done. He gave me an enigmatic grin and said that those charts don’t apply to his yeasts—but he wasn’t prepared to divulge how his lambic differs.

This wasn’t the first time I recognized the difference between Boon’s approach and Van Roy’s. Again and again, Boon discussed the science of lambic, the ways in which some of the wild variability of the microbiology could be tamed. Observing his new brewery, he pointed out what traditional once meant: “You don’t make better beer with cast-iron mash tuns. We had them because 120 years ago the oak mash tuns were stirred by hand. The old systems were okay when there was nothing else.” Everything is made to Boon’s specifications, even the pilsner malt he uses. (The German malts he once used are grown and dried too hot, and introduced compounds he didn’t like into his beer.)

Yet Boon does take time to practice some craft. When old staves rot and need to be replaced, Boon does the work himself. It’s the one remaining area where he has a completely hands-on role in the brewery. When we concluded our tour, he looked at his tuns of aging beer, resting quietly. “The finest flavors, the best esters, are built slowly. It takes time. Time, time, time. It’s a time-consuming way of making beer.”

Lambics, and especially gueuzes, live in that strata of artistic accomplishment that includes stinky cheeses, opera, and abstract painting. It’s very difficult to come to a gueuze cold and appreciate what’s going on with it. Once you get past the shock of the experience, you begin to understand the flavors and how they work together. Moreover, sampling bottles from different breweries makes it instantly clear what role the wild yeasts play. Gueuzes are a bit like dog breeds—they are distinctive and unique, and people have their preferences. I have discussed gueuzes with lambic fans and know some so devoted to Boon, Cantillon, Drie Fonteinen, or Girardin that they consider the preference for others a minor blasphemy. That kind of devotion is a testament to just how profound these beers can be. Is it a reflection of the approach of the brewer? Is that essence a part of the nature of the beer? In the case of lambics, almost certainly.

“If your brewery is on the top of the hill, you will always have less wild yeast. Temperatures in the night, for one reason, and also the wind. If you look at it from another side, the old English books will tell you if you’re going to build a new brewery, put it on the top of a hill and make the opening of your cellars from the north. To keep the wild bugs out. So if you put it close to the river and put the openings to the south, you will have much more wild yeasts. If you count wild yeasts in the air, you will find much more wild yeasts near a river than at the top of a hill; if you count bacteria, it’s about the same. And that is very interesting. Some people forget it’s spontaneous fermentation, not spontaneous acidification. The idea is to make a wheat beer that ferments with wild yeast.”

—FRANK BOON, BROUWERIJ BOON