The Tart Ales of Flanders

Belgium is divided along cultural and linguistic lines, the north occupied by speakers of Flemish (a variant of Dutch), the south by French speakers. Brussels is a crossroads for both. The top half of the country is known as Flanders; the bottom, Wallonia. So far, so good. The trouble is that the western half of Flanders was once a part of the French house of Valois, a region of Burgundy. If you sail past Belgium’s hop fields in the province of West Flanders, you enter French Flanders. And though they speak Flemish in the Belgian municipality of Poperinge, a few miles down the road in the Dutch-named Steenvoorde, France, they speak French.

Confused yet? It would be a relief to explain that the native beers exhibit none of the region’s entanglements, but alas, it’s not so. The beers made in Flanders are just as confusing. The balsamic ales characterized by Rodenbach are a dark red-brown but are by tradition called “red ales.” Their close relatives, known locally as oud bruins—sweet and sour and slightly meaty—which are brown with amber highlights, are called “browns.” Still other breweries make beers that share characteristics of both, and some qualities of neither. Unfortunately, the distinction grows ever more academic: These exquisite beers, echoes of the distant past, are slowly dying out. Even more than lambics, their future rests in the survival of a shrinking handful of producers. ■

A street view in Oostvleteren, typical of the small villages that dot the countryside in West Flanders

ORIGINS

TART FLEMISH ALES date back centuries in Flanders, where they have long been a regional specialty, extending as far east as Mechelen (just north of Brussels). But unlike their sour cousins near Lembeek, the group never formed a cohesive or enduring style the way lambics did. Writing in the 1850s, Georges Lacambre clustered them together out of convenience, acknowledging that they came “in a number of varieties …. It varies greatly from place to place and sometimes in the same locality; often in the same town there are not two brewers whose beers are the same.”

Throughout Flanders, people prized these beers and regarded their deep color a marker for quality. Remarkably, brewers achieved it not through the use of dark malts or sugars, but through slow caramelization of the wort over exceptionally long boils. Ten to twelve hours was the standard for the famous beers of Mechelen, and in West Flanders they were longer—sometimes an astonishing twenty hours. These intense boils must have produced heavy, concentrated beers loaded with caramel flavor. Of course, such a boil was arduous and expensive, so some breweries cheated, adulterating their beer with the mineral lime.

Current Flemish tart ales get their character from aging in wooden casks, and that practice goes back centuries. Practices varied in West Flanders, where the beer was considered ripe and palatable after three months. In Mechelen, breweries aged their beers up to ten months and, much as the famous producer Rodenbach does today, blended old stock with fresh beer. Interestingly, Rodenbach traces their own practice of blending beer to Britain. In 1872, a third-generation Rodenbach, Eugène, returned from a stint in England where he learned the secrets of porter brewing. Although vat aging was known to Flemish breweries, Rodenbach apparently wasn’t doing it. Eugène collected the first huge vats (foeder in Flemish, foudres in French) and began to age Rodenbach to achieve the kind of vinous acidity for which porters had become famous. (There may be another connection. Eugène’s grandmother, Regina Wauters, was a brewer’s daughter from Mechelen.)

Rodenbach’s beer has a pure, sharp tartness.

Tart ales remained popular well into the twentieth century. Following the wartime devastation, tart ales rebounded in the late 1940s and were still considered regional favorites into the sixties and seventies. Only larger, wealthier breweries were able to maintain large cellars full of foeders, however, and the number of breweries making wood-aged tart ales dwindled as cheaper lagers became popular. One of the great champions of these beers arrived in the 1970s and remained a fierce advocate until his death: the writer Michael Jackson. He was the first to attempt to place the dizzying variety of Belgian beers into categories or “styles,” and decided to split the Flemish tart ales in two. He didn’t have an especially good reason for this, though there is perhaps an admission hidden in this passage from Beer Companion:

The sweet-and-sour character is common to the brown ales of East Flanders and the ‘red’ of the West, and the two are brother brews. . . . Both interpretations have their origins in wood at ambient temperatures, before either stainless steel or refrigeration became available. Each is geographically in the corner of its country, and they have somehow survived.

For each style, the famous old breweries in Roeselare in West Flanders (Rodenbach) and Oudenaarde in East Flanders (Liefmans) stood as standard bearers for “the brown ales of East Flanders and the ‘red’ of the West” but they had less and less company. Jackson’s patronage may have saved these breweries, but his distinction between them stylistically is now hard to argue. (Even the east–west distinction might look strange to visitors noting that the breweries are separated by only twenty-five miles.)

Tart ales were seriously endangered when Riva, a large consortium of breweries, bought Liefmans in the early 1990s. The new owners quit the quirky old brewery in Oudenaarde and moved production to nearby Dentergem. In 2007, Liefmans was saved from liquidation by Duvel Moortgat. In an effort to find a wider audience, Liefmans has been cleaned up and some find the character has gotten less complex. A handful of other Flanders breweries, led by Verhaeghe, Bockor, and Van Honsebrouck, have kept the tradition alive, if barely. Verhaeghe is the only brewery besides Rodenbach and Liefmans devoted to this type of beer, while Bockor and Van Honsebrouck make just one example. These are desperate times for the style—even the Americans, reliable rescuers of lost styles, have had a hard time replicating the quality of the originals—and it may well dwindle further. A twinkle of possibility yet remains: Revivalists at De Dolle and De Struise, two modern Flanders craft breweries, have made impressive, accomplished twenty-first-century tart Flemish ales. ■

DESCRIPTION AND CHARACTERISTICS

PEOPLE HAVE SPENT well over a hundred years trying to categorize the differences among the brown ales of Flanders, but the beers have perpetually shifted and changed. In recent decades, writers have focused on two breweries as exemplars of style—Rodenbach and Liefmans—but this gave false coherence to a shaggy collection of different products. Looking at the survivors that still manage to produce beers in the lineage of tart dark ales, you see almost as many unique examples as there are breweries—the idea of “styles” isn’t much use to us in a consideration of tart Flemish ales.

The region’s most important brewery is Rodenbach, and not just because it’s the most famous. Rodenbach uses a mixed culture of yeasts, and ages their beer in immense vats—the largest are 8,000 gallons—for up to two years. During that time it acidifies to a pH even more extreme than lambic’s. Until the 1970s, Rodenbach used a cool ship and fermented their beer spontaneously, and until Palm acquired the brewery in 1998, it supplied its multistrain yeast to many of the area’s breweries—Verhaeghe, De Dolle, Liefmans, and Strubbe along with others that no longer make soured browns. The shift to “mixed fermentation” signaled a change at Rodenbach, and the breweries dependent on Rodenbach’s yeast changed when they could no longer procure fresh cultures. Even in the past few decades, the “traditional” beers have evolved.

Of the tart ales of Flanders, Bellegems Bruin is the smoothest and least sour.

Flemish red? Flanders oud bruin? A rose by any other name …

Let’s start with Rodenbach. The brewery selects the very best lots to bottle separately (a rare practice) but mainly uses wood-aged beer to blend with fresh ale. Regular Rodenbach uses 25 percent vintage ale, and Grand Cru 75 percent. The former is a quite sweet ale lightly kissed by tartness, a versatile partner for food. (After tastes changed, Rodenbach had to sweeten this blend, and some older fans still chafe at the decision.) Grand Cru depends on what brewer Rudi Ghequire calls the “triangle of taste”—sweetness, dryness, and acidity. The dryness and acid come from the aged ale, which can reach 98 percent attenuation. Fresh beer provides a bit of the sweetness and effervescence, but equally important are esters that develop during the long maturation. The esters give Rodenbach Grand Cru the unmistakable flavor of balsamic vinegar that comes from acetic and lactic acids as well as their associated esters.

Brouwerij Verhaeghe in Vichte, just southeast of Roeselare, follows a similar process to produce its signature Duchesse de Bourgogne; Verhaeghe also produces a dry, woody, unblended product called Vichtenaar. As with Rodenbach, the nature of the sour is distinctly balsamic.

Liefmans old brown ales are also similar, but there is one noteworthy difference. The brewing is handled off-site; fermentation, carried out in the old location at Oodenaarde, happens in open fermenters with mixed fermentation. The biggest difference from the beers brewed in Roeselare and Vichte is that Liefmans is aged in steel. Blends of Oud Bruin are made from three-to-four-month-old beer; Goudenband is aged at least a year.

But others approach their beers in completely different ways. Brouwerij Bockor, in Bellegem, makes their beer by blending a brown lager with spontaneously fermented ale aged eighteen months. The character for this beer oscillates between a smooth, neutral brown and a lightly sour ale. The Van Honsebrouck brewery also makes a brown called Bacchus using this method. By contrast, Bavik ages a strong pale beer for two years in oak tuns. That beer becomes Petrus Aged Pale, but the brewery also blends some in with a lighter, fresh brown ale to make Oud Bruin. Finally, De Dolle Brouwers have experimented with a number of different methods to make Oerbier, but currently use a very traditional (read: nineteenth-century) brewing method that involves a long boil, settling the trub (sediment) in a cool ship, and sour aging in steel.

All of these beers bear some resemblance, but they are distinctive. Verhaeghe and Rodenbach have vinegar notes and pure, sharp tartness. Bockor Bellegems Bruin has a similar nose, but is smoother and lacks the balsamic sour of Rodenbach. De Dolle is a huge, deep beer with a dry, austere finish. Liefmans has a sweet-and-lactic-sour character that is less complex but more comforting. Bavik Petrus Oud Bruin is woody and bitter, but has a nonbalsamic vinegar note that sharpens the palate. Their differences make them one of the most interesting families of beers, and each deserves to be sampled once. ■

BREWING NOTES

WE’VE ALREADY TOUCHED on some of the variation in methods, but it’s useful to drill down and look at a couple of important (if not universal) aspects in brewing tart Flemish ales: mixed fermentation and wood aging. Spontaneous fermentation isn’t limited to the area around Brussels—brewers in Flanders still do it to make tart ales, and Rodenbach’s legendary strain of yeast originally derived from spontaneous methods. Most breweries now used a process called “mixed fermentation”—a blend of wild cultures pitched rather than harvested wild in open cool ships.

No one can describe the process better than Rodenbach’s brewer, Rudi Ghequire.

In our process, we work with a yeast culture with eight different yeast strains and also a little bit of lactic bacteria. During the first week, we have an alcoholic fermentation from the yeast cells, and after one week the lactic bacteria take over. During the lagering time [four to five weeks] we reduce the yeast cells in the beer by precipitation, and then we send a nearly bright, young beer to the wood. The big difference between spontaneous fermentation and mixed fermentation is with spontaneous you send wort to wood and we send young beer. Beer has an alcoholic protection, so it is less risky. When you reuse yeast from spontaneous fermentation, you have arrived at “mixed fermentation.”

The process of aging beer on wood induces subsequent changes that give these tart ales their unique quality. Although the oak tuns contain resident wild yeasts and bacteria, they only inflect the already inoculated beer. Rather, it’s the action of oxygen that makes the difference. Some microorganisms are anaerobic, working in the absence of oxygen, while others, like Brettanomyces, are aerobic. Wood is porous and allows oxygen to feed aerobic yeasts and inhibit anaerobic bacteria. But equally important is the amount of oxygen entering the beer—a factor dependent on the size of the foeder and the thickness of the oak slats. The larger the tun, the less beer will be in contact with oxygen; the thicker the stave, the less oxygen. Standard-size wine barrels let in about ten times the amount of oxygen as Rodenbach’s massive tuns.

Goudenband is aged at least a year.

This is one of the reasons American breweries have had such a hard time reproducing the balance of acids and esters that give Belgian beers, aged in foeders, their rich complexity. Wine barrels activate the Brettanomyces, which dry the beer out, reducing the perception of sharp acid typical in foeder-aged Flemish beer. A few breweries have found larger European wine tuns (Boulevard, Tröegs, and New Belgium, to name a few), but it is hard to find the fine-grained European oak vessels favored by brewers. Those two elements—mixed fermentation with wild yeasts and bacteria, and slow aging in large foeders—are key to these beers.

Recipes for tart Flemish ales are fairly similar. Pale or Vienna malts, caramel, corn, and sugar are common. Hopping is used for its antibacterial qualities, not for bitterness or flavor. In most Flemish tart ales, hops fall below the flavor threshold. The beers enjoy relatively long boils of two hours or more—which, while long by modern standards, is well below the boil lengths for lambics.

The beer resting in the foeders is judged ready not when it reaches a certain age, but when the brewer determines it tastes complex and ripe—a moment that may come months apart for different batches in different tuns. When the beer is ready, brewers blend various batches of aged beer into a single mother-batch that itself gets blended with younger beer, or in some cases sold as is. Even in highly technical breweries like Rodenbach, this is still done by tasting, though chemical analysis confirms their work. ■

EVOLUTION

THE TART ALES of Flanders suffer from misunderstanding, obscurity, and general weirdness, but at least brewers have more latitude in their methods than do lambic makers. This may be their salvation. More than thirty years ago, De Dolle Brouwers—the “mad brewers”—became pioneers in resurrecting old brewing styles. Indeed, they resurrected a nearly lost brewery, acquiring a creaky old place in Esen, near the French border, that dates back to the 1840s. They could be called one of the first Belgian craft brewers—one of the first craft brewers, period—but the partners are more like cultural archivists, saving and preserving tradition. Their first beer was, appropriately, a tart Flemish ale. They called it Oerbier, where “oer” has the same sense as the German ur—original. It was their original beer, but the meaning really suggests the original beer of the region, the ur-Flemish brown.

Oerbier has gone through several incarnations, originally using yeast from Rodenbach. When that became unavailable, Oerbier became a regular strong brown—“like a Trappist,” says founder and brewer Kris Herteleer. Now Oerbier goes through a separate mixed fermentation, though in steel tanks. One small batch, Oerbier Reserva, was put on cask and it was a huge success; the brewers hope to do more in the future.

The beer goes through a classic long boil of up to three hours before resting for an hour in a cool ship—not to attract wild yeasts (the beer is too hot), but to settle out particulates. It’s a technique Lacambre lauded in the mid-nineteenth century, one he felt didn’t have the disadvantages of the newfangled English chillers that failed to remove the trub. Much like the nineteenth-century brewers, De Dolle’s Harteleer is also a big fan of long boils, which “thank much of their flavor to the … [Maillard] reactions” that caramelize the malt. (Maillard reaction describes a chemical process of browning that gives seared steak, baked bread, and dark ales their tasty flavors.) But for De Dolle Brouwers, the long boils produce richer malt flavor and a deeper bitterness. In a wry aside, Harteleer admitted that brewing scientists now think long boils damage a beer’s shelf life and “with their new testing machinery, they are even able to prove it.” Harteleer is unpersuaded, and it’s hard to argue with the highly praised beers De Dolle makes.

Another new brewery steeped in the region’s history is De Struise Brouwers—“The Sturdy Brewers.” The brewery was originally founded at an ostrich farm, and the word for “sturdy” is a play on the Flemish word for “ostrich”—and why an ostrich appears on their official seal. De Struise makes a much larger line than De Dolle and wanders more readily into modern craft beer styles like imperial stouts. Its flagship is Pannepot, a beer with a personal connection to the brewery. The beer takes its name from a small fishing vessel of a type owner Carlo Grootaert’s great-grandfather once used to ply the waters near De Panne for herring. It is fashioned on an old homebrew made by the wives in the family. They had a unique system of mulling it by plunging a red-hot poker from the fire into the beer, which had the secondary effect of caramelizing it. De Struise approximates that homebrew with the thick Pannepot. “The label is actually my great-granddad’s boat, the B-50,” he told me.

But De Struise’s greatest brewing achievement is a rare one, limited by their cask capacity. Called Aardmonnik, it is a strong brown ale with a pronounced tartness, aged two years in wine barrels inoculated with lactic bacteria—no Brettanomyces. The final product is blended to produce a complex beer of sharp sour and rich, sweet malt. Like the brewers at De Dolle, the Sturdy Brewers are keen to revive old traditions.

These types of beers have not been brewed to distinction outside Flanders—with one notable exception. Colorado’s New Belgium Brewing produces a beer called La Folie that has all the complexity and depth of the originals. It’s not surprising. The brewer at New Belgium, Peter Bouckaert, came there from Rodenbach. A part of the Lips of Faith series, La Folie is a beer worthy of a Rodenbach brewer. ■

THE BEERS TO KNOW

EVEN PITCHING the largest tent under which all these ales might gather, they constitute a sadly short list. Some of these beers are readily available, though, and are musts for anyone unfamiliar with the tradition. They’re also handy to have around when you have wine drinkers visiting, especially those who maintain a distance from beer—give them a tart ale from Flanders and see how their opinions change.

RODENBACH GRAND CRU

LOCATION: Roeselare, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed variety of pale malt, roasted barley, corn grits

HOPS: Locally grown (varieties change year to year)

6% ABV

It’s worth beginning with a bottle of regular Rodenbach, containing 25 percent aged stock, so you can triangulate when you try 75 percent old stock Grand Cru. The latter is obviously more sharply tart, but what surprises are the higher levels of fruity esters, which fool some people into believing cherries have been added. Grand Cru is a dry beer, but esters fool the palate into thinking it’s sweeter—this is the chemistry that makes the style sing. From time to time, Rodenbach releases single-foeder, undiluted stock—a beer with nearly no remaining sugars that is nevertheless rich and tastes of cherry. Grand Cru is one of the world’s great beers, and every beer fan should try it at least once.

VERHAEGHE DUCHESSE DE BOURGOGNE

LOCATION: Vichte, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

6.2% ABV, 1.065 SP. GR.

The Duchesse de Bourgogne is Verhaeghe’s answer to Rodenbach Grand Cru—but the brewery offers a slightly lighter, sweeter take. Many of the elements are consistent with Rodenbach and yet the Duchesse is more vinous, with a wine-skin astringency. If you’re trying to convert wine-loving friends to beer, this is the one to start with.

VERHAEGHE ECHTE KRIEK

LOCATION: Vichte, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

OTHER: Limburg Province cherries

6.8% ABV, 1.065 SP. GR.

One way to assure consumers you’re not using flavoring syrups is to call your beer “Real Cherry”—as does Verhaeghe, in Flemish, with Echte Kriek. One of the only remaining examples of a once-common variation, Verhaeghe’s illustrates how well the elements of brown ales, acid, and cherries come together. Even more than lambics, the chocolatey malts in a brown ale really allow the cherries to pop—and everyone knows what a great combination cherries and chocolate are. Drying tannins attest to the presence of actual fruit.

DE STRUISE AARDMONNIK

LOCATION: Oostvleteren, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

8.0% ABV

The balsamic aroma wafting off Aardmonnik marks it as an authentic Flemish tart ale, but the scent is somewhat deceptive—on the palate there’s far more chocolate, wood, and malt. It’s quite a bit darker and richer than the typical Flemish; an almost stout-like quality that adds balance to drying acid. A rare beer released in small lots, this is one of the finest examples from the region.

LIEFMANS GOUDENBAND

LOCATION: Oudenaarde, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Undisclosed

7.9% ABV, 1.075 SP. GR., 6 IBU

Goudenband has long stood as the “oud bruin” counterpoint to the “Flemish red” of Rodenbach. They are different. Goudenband has much more fresh malt character, sweet and raisin-like, cosseting the tart balsamic notes. It’s something like Chinese sweet-and-sour sauce; where the currents cross you find a cinnamon and port. The body of this brown is surprisingly light and effervescent. Liefmans is less intensely sour than Rodenbach and has a light, candy-like sweetness that makes it more approachable.

DE DOLLE BROUWERS OERBIER

LOCATION: Esen, Belgium

MALT: Undisclosed

HOPS: Poperinge-grown Whitbread Golding

OTHER: Dark solid candi sugar

9.0% ABV, 1.083 SP. GR., 30 IBU

Oerbier is a strong brown ale acidified slightly by Lactobacillus. It doesn’t possess the characteristic balsamic note of some Flemish tart ales, nor is the tartness aggressive. Rather, the beer is smooth, coruscating, and mildly tart. It’s woody, dry, and fairly hoppy as well. Oerbier, De Dolle’s bid for an ur-tart ale, may or may not be the original Flemish ale; with luck, it could be Flemish ale’s future.

ROESELARE, BELGIUM

Rodenbach

THE ART OF WOOD AGING

THE TOWN OF ROESELARE SEEMS MORE MODERN AND BUSTLING THAN MANY OF THE SLEEPY, MEDIEVAL TOWNS THROUGHOUT WEST FLANDERS. THERE’S A REASON FOR THIS: ROESELARE, LOCATED ON THE FRONT LINES IN WORLD WAR I, WAS LARGELY WIPED OUT. AFTER THE WARS, THE CITY REBOUNDED AND IS NOW A HUB OF INDUSTRY AND TRADE. FOR NEARLY TWO CENTURIES, THE RODENBACH FAMILY HAS BEEN AT THE CENTER OF COMMERCE, AND FOR NEARLY AS LONG, RODENBACH HAS KEPT ALIVE THE MOST TRADITIONAL METHODS OF FLANDERS BREWING.

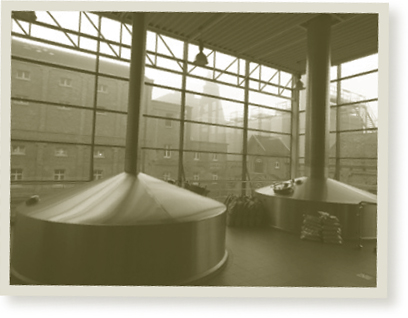

When Rudi Ghequire, the master brewer at Rodenbach, took me on a tour of the brewery, we spent less than ten minutes in the actual brewhouse. We spent a similar amount of time on the history of the brewery (even though history is a big deal at Rodenbach) and a few minutes on fermentation. But our tour lasted two hours. The remainder of our time? We spent it inside the maze of cellars that contain the massive vats of aging beer.

The old maltings building, now a museum

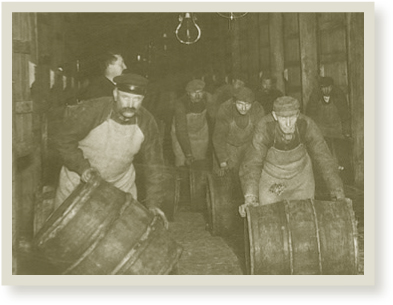

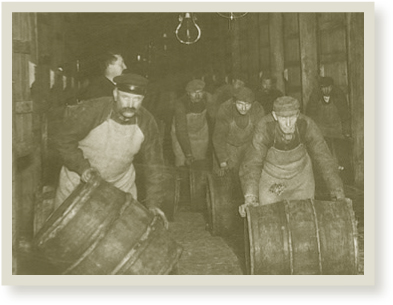

Except for the mustaches, little has changed at Rodenbach in the last 100 years.

This is not incidental. Rodenbach takes care making its beer—the new owners, Palm, spent a boatload of money on a beautiful new brewery after purchasing it in 1998—but what happens in the mash tun and kettle aren’t the main event. The real action happens in those famous oaken foeders. There are 294 of them altogether, and they’re housed in ten vast cellars that can hold up to thirty-three each. The smallest are 120 hectoliters (roughly 100 barrels or 3,200 gallons) and the largest are a whopping 650 hectoliters (550 barrels/1,700 gallons). Many of them are very old—the brewery says “older than 150 years” but they’ve been saying that for a while. The three oldest date back to the 1830s. The brewery has its own cooperage, not for building the vats but for maintaining them. This is how their version of an acidified red ale has been made for well over a century. Inside the vats, a happy little colony of wild yeasts work away for months, adding lactic acid to the beer and dropping the pH. This is where Rodenbach is truly made.

When it comes time to bottle the beer, Ghequire leads a team of tasters who blend the vintage beer to get the character they want. They taste the beer in each foeder and begin to construct a blend from a combination of vats that have the proper character. Each vat is its own ecosystem, so the beer coming out will taste different vat to vat. On the day I visited, Ghequire pulled out a “key” that opened the valve on the foeders. We tried samples in different cellars and of different ages. One was so sour it made me cough. Another was chocolatey. In one, Ghequire tasted the kiss of Brettanomyces—a flavor that doesn’t appear in Rodenbach’s beers. It was too subtle for me to detect, but he made a mental note of it. “We’ll have to blend that out,” he said. Once they have a final blend of vintage stocks, they will combine that back with fresh beer to make Rodenbach and Grand Cru.

Brewer Rudi Ghequire

A line of foeders

Oak drying in the cooperage

Rodenbach’s baroque production methods would only be worthy of a footnote if the beer were ordinary. Of course, it’s not. Regular Rodenbach is a lovely session tipple that has surprising versatility with food and Grand Cru, a blend of two-year-old foeder-aged beer (75 percent) and young beer (25 percent), is simply one of the world’s best beers. Americans are adept at re-creating most styles, but approximating Rodenbach is tough; Ghequire believes this is entirely due to the wood. Without the interaction of wild yeasts and the tiny bit of oxygen that permeates the grain, beer can’t develop the depth and character Rodenbach has. Those giant tuns are central to the process, too. Because very little of the beer is in contact with oxygen-permeable wood, it ages very slowly. It’s much harder to do this kind of beer with small tuns or wine-sized casks. Ghequire says the 180-hectoliter vessels are ideal.

Of all the breweries there are to visit in the ancient brewing countries of Great Britain, Belgium, Germany, and the Czech Republic, Rodenbach may be the most awesome. Every older brewery I visited discussed the balance between tradition and efficiency—an important consideration for a commercial enterprise. But Rodenbach is off the charts in terms of the expense and inefficiency it takes them to produce a single bottle of beer. No modern company would or could consider the Rodenbach model. The vats alone cost thousands of dollars, never mind the cellar space. Add to that the notion of vatting beer for two years—an absurdly expensive venture. And yet here the brewery is, putting beer in vats and then trying to compete in a marketplace where industrial lagers can be made in a fraction of the time and for a tiny fraction of the cost.

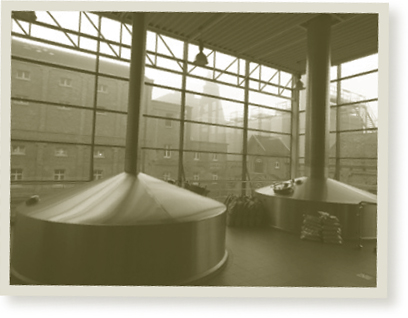

The new glass-walled brewhouse is ultramodern, but the beer becomes Rodenbach in the cellars below.

It’s no surprise that the tart beers of Flanders are on the endangered species list. Very few brewers make authentic ones, and none make them the way Rodenbach does. It is almost impossible to imagine any brewery will join Rodenbach in the near term, either. If we could designate breweries as “World Heritage” sites that would never fail because of commercial pressures, I’d put Rodenbach at the front of the list. In the world of beer, there’s nothing like it, and we are fortunate indeed that it has survived the vagaries of wars, depressions, and modernization. Fortunately, we can all act to protect this institution by drinking a bottle of Grand Cru now and again.