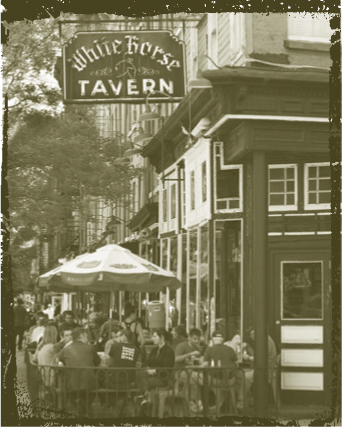

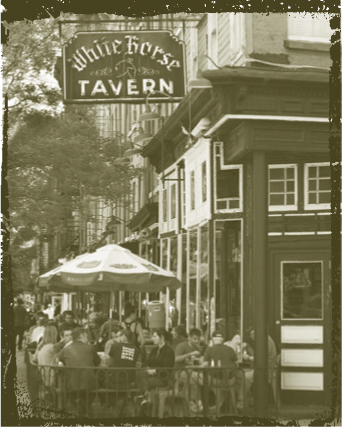

The storied White Horse Tavern in New York City’s Greenwich Village has been in business—largely unchanged—since the 1880s.

If ever there was a place designed to soothe and cheer, it was the humble corner pub. On a chill night, a pub means warmth and conviviality; on a hot summer day, the patio is a wonderful place to enjoy a cold one. The notion of drinking together seems to go back as far as Sumer—to the original brewing culture—when drinkers sat around a vase of beer with straws outstretched, drawing it in communally. The Celts maintained pubs, and Romans established roadside watering holes for travelers during their occupation of Britain—an auspicious activity that the natives have happily maintained ever since.

In the United States, taverns have their own illustrious—and notorious—reputation. Boston’s Green Dragon, established in 1654, was peopled by luminaries like Paul Revere and John Hancock, and it was there that locals overheard British soldiers discussing the attacks on Lexington and Concord. Like a good fish story, it doesn’t actually matter if it is true—a tavern tale is affirmed by its deliciousness. Philadelphia’s elegant City Tavern served as an unofficial meeting place for the First Continental Congress. And of course, New York was home to legendary speakeasies like Chumley’s, where the phrase to “86” someone or something was born (it referred to the entrance at 86 Bedford Street, out of which boozy scofflaws fled). Other famous pubs have been home to mobsters, working girls, poets, and presidents—every town’s history is more entertaining when told through the lens of its pubs.

Unfortunately, the pub as institution fell on hard times after Prohibition, and before craft brewing came along, had often been relegated to the margins—a smoky, windowless box made to protect the “respectable” public from sight of the drinkers. We call them dive bars now, but in the 1970s and ’80s, they were just bars. This state of affairs reflected another aspect of the American experience—our long, conflicted relationship with booze. As a culture, we’re not completely comfortable with alcohol. Someone’s always trying to consume it, and others are trying to inhibit its consumption. The windowless pub was a way to sequester the drinkers from the nondrinkers, but it meant that pubs remained haunts mainly of men, with doors decorated by “no minors allowed” signs.

The storied White Horse Tavern in New York City’s Greenwich Village has been in business—largely unchanged—since the 1880s.

By the time the twenty-first century rolled around, things had changed again. Windows are back, and with them, women and children. Drinkers are interested in the alchemy of food commingling with beverage in the mouth, and go to pubs to eat as well as drink. One recent manifestation of this is the “gastropub”—a high-end pub where the menu and taplist are selected to complement one another. The arrival of good beer has brought flavor back into the equation and, perhaps with a little help from drunk-driving laws, moderation as well. Only one in ten beers is served on draft, but for the first time in decades, that number is ticking upward, not down. Pubs have come back into American lives, at least for a time, and conviviality is back on the agenda. ■

ONE OF THE more interesting things about foreign travel is how the unnoticed, little aspects of life we take for granted shift and change when we cross the sea. Going to a bar involves all kinds of specialized knowledge that we’ve long forgotten, but visit another country and we’re reminded of just how many little social agreements there are. Take, for example, the word “bar.” This is an Americanism, and it isn’t specific. We may use it as shorthand to describe a place with no food, but with a pool table and cheap beer—or it could refer to the brass-and-oak taproom at a high-end restaurant with twenty-dollar entrees and eight-dollar pints. (Oh, “entrees”? In French that means first course, not main course. See what I mean?) We use “pub,” “tavern,” “bar,” “lounge,” and “brewpub” to describe different kinds of drinking establishments, and we know that they can mean slightly different things. Imagine the confusion to a foreign visitor.

It turns out that ordering a pint always involves interacting with local culture, expectations, and mores. It would take a book—a lovely, gorgeous book—to describe the practices of every country, but here are notes on the habits in those most famous of brewing countries.

In Britain, the standard unit of measure is a pub. Unlike the convoluted naming system we use in the U.S., in Britain a pub is a pub is a pub. Some are very elegant, with dark wood covering the walls, crystal lights, and polished brass, while others are more spartan. But from the lowliest to the most elegant, British pubs have a cozy, welcoming feel. Chatting is encouraged, even among complete strangers. Ask the bloke next to you at the bar about the beer he’s drinking and you’ll be off to the races. In no place on Earth is the act of buying a beer a more genial experience.

Everything is very straightforward. You walk up to the bar, order your pint, and take it back to your table (or enjoy it right there at the bar). You order food at the bar as well—but someone will bring it back to you. When drinking with friends, it’s typical to buy beer in rounds, a process that encourages one to stay on past the first pint. (When it’s your turn say, “It’s my shout,” for extra points.) Tipping is not typical, but if you spend a whole evening in one pub, you might throw in a pound or two after the final round for thanks. In an enormously controversial move, the U.K. government banned smoking as of 2006 and 2007 (Scotland was first, England last), but pubs seem to have survived the shock.

A quintessential British pub

In the south of England, a pint will be served au naturel, straight from the cask. This method has the virtue of authenticity—you’re getting unadulterated, pure beer this way. Detractors note that the method produces a thin, big-bubbled head of little beauty. In the north, they use a “sparkler” to produce a creamy head, much like one from a nitrogen tap. Critics of this method feel that in frothing the beer, the sparkler changes the experience of the pint. The sparkler is the subject of intense debate that shows no signs of letting up.

If you do walk into a pub, don’t be surprised to see a preponderance of men. Beer drinking is still the purview of men, perhaps a cultural artifact of the pub. If you do see women, they’re as likely to be drinking wine as beer. Beer companies are trying to rectify this by introducing “women’s beer”—froufy products masquerading as white wine—but the image of an old codger sitting at the bar is the real culprit. As in the United States, women have embraced craft beer, and this may be the thing that finally turns the tide. The progress has been slow to date.

Beer is ubiquitous in Belgium, and so the difference between a restaurant and a bar is slim indeed. “Café” is a more common word than pub. As in the United States, you can choose to sit at the bar, but if you sit at a table, you order through a server. Belgian beer cafés are not quite as uniform as British pubs. Most are airy and bright, with a greater emphasis on the table than bar. One fascinating cultural proclivity involves wall ornamentation—beer paraphernalia, photos, magazine covers, shelves with tchotchkes. Sometimes I was less certain I was in a bar than in a museum.

Unlike Britain, in Belgium the majority of specialty beer is sold in bottles, not on tap. That’s largely a function of the beer itself, much of which goes through a secondary fermentation in the bottle. Because of this, presentation is a big part of the experience, and the server plays no small role in the ritual of decanting a beer. The procedure begins with the proper glass: Not only does every brewery have its own specially shaped design, but a brewery may have a glass for every style of beer it brews. Lambics are the most baroque; a gueuze may be poured from its own little basket and the bottle left to recline with its neck raised, while faro is transferred to an earthenware pitcher. The server is aware of the level of carbonation—variation is tremendous—and decants the beer to produce the perfect head. Because Belgian beers are bottle conditioned, they contain a skiff of yeast at the bottom of the bottle; the server will stop before the entire beer is emptied to keep the yeast in place. You may add it yourself, clouding the beer, or drink it separately. Finally, the server will deposit the bottle in front of you, turning it so you can read the label. As in Britain, tipping is not expected.

In Belgium, women drink beer. In cafés and restaurants, women are equally likely to be drinking a goblet of tripel as their dining companion—who may be a woman drinking a tulip of blond. In fact, everyone drinks beer. It was even the case that children were served beer at school—“child’s beer” was a form of bière de table—though that tradition foundered in recent decades. Even now, children over sixteen may enjoy a glass at a restaurant with their parents. Smoking, partially banned in 2007, was fully abolished in 2011.

I entered my first German tavern, Zum Schlüssel in Düsseldorf, groggy after an international flight. Drawn in by the cozy (but full) room visible from the street, I made my way back around the bar and discovered a cavernous pub spread across a few rooms. It wasn’t unusual; the central feature of the German beer hall is its immensity. Some are honeycombed with smaller rooms and niches, but some are as vast as ballrooms. It turns out Schlüssel, which seats four hundred, isn’t an especially big place—Munich’s Hofbräuhaus seats three thousand. But beyond size, German taverns are suffused with ritual, culture, and local custom.

Munich’s formidable Hofbräuhaus welcomes thousands of imbibers.

Walking into an unfamiliar German tavern can be disorienting. Even the small pubs are likely to be spread out across more than one room, so finding a seat usually means exploring. Rarely will someone seat you, though servers are happy to help you find a place if it’s busy. The typical pub has large tables, and parties sit where there are free seats. In Germany, sharing tables is part of the community vibe. In the pub at Füchschen Brewery, I was joined by a group of three drinkers at a standing table the size of a large pizza. We put our glasses on the table and stood back to make room for each other. Taverns have a distinctly ecclesiastical feel about them—stained glass is common, and I was amazed by how many crucifixes I found. (Maybe this shouldn’t be surprising; brewing and the church are the oldest institutions around.) There is region-to-region variation, and no place is as distinctive as Bavaria, where it seems like every place has blond wood tables, antlers on the wall, and dark paneling throughout.

In Germany, everyone drinks beer. Taverns are gathering spots, and it seems like the whole city can be found inside them. Young people, old people, men and women—everyone enjoys a pint (make that a half-liter) down at the pub. Pubs are so much the center of community life that they often reserve tables for regulars. In towns like Bamberg, this is mystifying to the tourist. I walked into Spezial Brewery a little before seven o’clock one Friday night and found the place thrumming with life. When I tried to sit in one of the three or four vacant seats, locals gave me a firm talking-to. Those tables were reserved for regulars who, right on cue, showed up to claim their seats just before seven. I had a half-liter and milled around by the bar to drink it.

Servers are attentive, but not intrusive, and habits have evolved to make sure people get their beer. The practice of bringing fresh glasses and adding a tick mark to the patron’s coaster is codified in Cologne and Düsseldorf, but other places use the tick-mark system as well. Usually a simple nod of the head to the server is enough to ensure a fresh pour. At the end of the session, though, you do have to summon your server. Unlike in the U.S., he will never leave a bill unless you request it. More commonly, the server will have a sturdy belt with pouches holding cash and each patron’s tab and will make change on the spot. It is customary to offer a small tip, usually by rounding up—you would pay 25 euros on a tab of 22.5. In Germany, smoking is regulated by the state, so check before you light up.

There are many ways in which the Czech Republic and Britain are kindred spirits. The use of floor malts, for one, and the devotion to zesty little session beers is another. The pub is the most obvious connection, though. Like the British, Czechs favor a comfortable and inviting little nook. No two pubs are alike, but they have a feng shui that makes you want to settle in and never leave. Publicans favor cozy spaces, wooden paneling, and pleasingly worn seats.

Navigating to a seat can be a slightly mystifying process. Czech public houses do have bars, but they’re not the center of attention—sometimes you can’t even sit at them. Instead, look for a free table—as in Germany, the pubs often sprawl across connected rooms, so wander around. As you circle looking for a table, you may also discover signs on free tables marked “reserved.” Apparently, back in the days of Communist rule, staff would sometimes scatter these around the pub to limit the number of tables they had to tend, and I’ve felt that same practice was at work on a couple of occasions even recently. More often, it’s a way of herding the crowd into a manageable cluster. And as in Germany, sometimes tables are permanently reserved for regulars.

Once seated, you’re golden. Czech servers are responsive and warm. I once found a pub in Prague that had a wonderful little back room. It was midafternoon and I was the only one in the room and yet, every time my mug started to reach a dangerously low level, my waitress magically appeared. The Czech language is a bear to learn (I never really mastered the word for “thank you,” děkuji—which is pronounced something like Dye kooye), but the servers are willing to work with you—by semaphore if necessary. Smoking is allowed in Czech pubs, but often only in the evenings. Although Czechs don’t tip, the koruna (“crown”) is worth so little that you can safely round up without offending your server. ■

IMAGINE THE SCENE: You’re out with a group of friends and the publican has just dropped fresh, foamy mugs of beer in front of you. What’s the next thing that happens? In a good many places around the world, some sort of toast or salute. In some, to skip this step would be freighted with tons more meaning than stopping to acknowledge it. I have sat around tables where drinkers merely nod to one another, and others where clinking glasses with your neighbor is adequate. In yet others, each person must clink glasses with every other drinker, making eye contact with each. Sometimes, we clink the base of our glasses. “Cheers!” we trill, or Sláinte, or Na zdraví, or Prost! Have you ever wondered why?

It starts with the human instinct toward ritual. We often think of rituals as religious, but they are just as often social. We shake hands or kiss each other’s cheeks in greeting; hand out cigars at childbirth; sing songs at birthdays. They reaffirm our connections and help us mark important milestones. We use ritual in life’s most significant moments, but also its most prosaic.

Throughout the world and across the centuries, a great many of our celebrations and commemorations involve alcohol. Rites of passage—to adulthood, at weddings, graduations, and funerals—often involve alcohol. We christen boats with bottles of Champagne (I’ve seen breweries get the same treatment—but of course with bottles of rare beer), and in some cultures the purchase of a new home means breaking out the bubbly.

There’s a reason we use alcohol. Although different alcoholic beverages have status associations (Champagne high, beer typically low), in general we think of alcohol as a social leveler. People go to public places to drink, and in them, the status differential between a business owner and his line workers falls away. The mood-altering effects of alcohol help facilitate bonding, which in turn helps integrate diverse groups. And, because it is spirituous, alcohol has a quality of power and transformation. We could mark special occasions with lemon soda, but alcohol is an accelerant, a way of magnifying our celebratory joy. It has potency.

Our tradition of “toasting” one another goes back more than a thousand years, starting with the drinker’s salute in Middle English, wæs hæil—a wish to be healthy or fortunate. We get the word “wassail” from this, and that term goes back as far as Beowulf:

The rider sleepeth,

the hero, far-hidden; no harp resounds,

in the courts no wassail, as once was heard.

There is a beverage historically associated with this salute, and with it we near the origin of our word. Traditionally the drink was warmed, and contained at least a portion of beer among its ingredients. In those very early days of Middle English, there were no hops, so the beer was spiced and usually spiked with liquor or mead. As hopping came along, the preparation depended on mulling without boiling, lest the potion get too bitter. Different wassail recipes called for all manner of varying ingredients, from fruit and sugar to eggs—and usually something stronger for added booziness. The Georgian-and Victorian-era British had to suffer through winters without central heating, so they found their warmth in liquid form. They used special bowls to serve the mixture, adding a communal and ritual flair. One of the most common ingredients, as early as the thirteenth century, was crisped bread floated on top of the bowl. In other words: toast. The combination of wishing people well and drinking from a common vessel eventually became codified, linguistically at least, to our practice of toasting one another’s good health.

Given the breadth of different cultural rituals, the expressions for “cheers” have a lot in common. In Romance and Slavic languages, drinkers toast to health. German and Dutch have a similar sense taken from the Latin. In China and Japan, the notion is closer to “bottoms up.” All of which are familiar enough—even if the sounds of the words aren’t, to English-speaking ears. ■

BEFORE THE ADVENT of the abomination known as the sports bar, people went almost exclusively to pubs to drink. To pass the hours, they invented games, interactive ones that the drinkers played, rather than games they watched with mouths agape. Some of these—Shove Ha’penny, Aunt Sally, and Toad in the Hole—are in what we’d call declining status. Others, like darts, shuffleboard, and pool, are going strong. Pub quizzes have, in recent years, become the rage across the country. Following are the rules for some barroom classics.

The most iconic of all the pub games involves beer and sharpened projectiles—obviously a winning combination. If darts earns demerits for anything, it’s the reliance on math, which slows the game in later rounds. The goal is simple. Beginning with 501 or 301 points, players take turns trying to reduce the total to zero, subtracting the amount where their dart lands on the board. Each player is given three darts a turn, and the final throw must land either in the bull’s-eye or doubles segments (a rule novices often spurn). The board is divided into twenty slices, each marked with a value. There is a narrow band at the outer edge worth double the value, and a thin band about halfway between the edge and the bull’s-eye worth triple the amount. The bull’s-eye has an inner pupil and outer iris worth, respectively, 50 and 25 points. The fewest throws a good darts player needs to reach 501 is nine. How many do you require?

The game of skittles is bowling’s great-grandfather. Inconveniently played outdoors, punters figured a way to turn it into a pub game.

Sophisticates refer to it as billiards, but in a standard-issue American bar, everyone else calls it pool. In the days before craft brewing, pool was ubiquitous in barrooms across the country. The only thing to do in bars was drink, so shooting pool helped pass the time. Although pool sharks may play games like nine-ball or straight pool, the game invariably played by the average pubgoer is eight-ball. The rules are so simple most kids know them—you’re either stripes or solids, and the first one to knock in all her balls plus the black eight ball wins—which accounts for a large part of pool’s popularity.

Pool tables take up a lot of space, and they are an increasing rarity in urban bars where each square foot costs a king’s ransom. As a result, bars with pool tables maintain a kind of louche credibility—they become markers of a blue collar, drinking-man’s environment. Facility at the pool table is another marker of barroom credibility, and a time-honored system ensures that the best players hold the table at busy bars. Newcomers can ask to play the winner, but lose to the local king and you’re back to your pitcher of Pabst Blue Ribbon.

In rare cases, you might encounter a gigantic table with a bunch of red balls. This is snooker, an English game. Like cricket, no one knows how it’s played.

My choice for best beer-drinking diversion is the noble game of shuffleboard. Apparently the world doesn’t share my opinion, because the number of tables has been on a steep decline since I first came of age. Let us hope for a retro revival (I’ve heard tales of one in certain cities). The easiest of all the games by far, the goal is to rack up twenty-one points by sliding weighted disks down an alley scattered with silicone beads. Four disks, and throwers alternate to facilitate defensive play, knocking a foe’s weight off the table with a satisfying clack. Some sticklers demand that only the farthest disk scores points (or disks if there are multiples of the same color). But in the majority of barrooms where I’ve played, we just tot them all up. After a good whacking, there are often few pucks to consider, anyway.

Once, during the longueurs of summer in between my freshman and sophomore years of college, friends and I invented a game in which we tossed a soccer ball into a laundry basket. If the shooter made his shot, the other player had to take a drink of beer. This is sort of the essence of the drinking game: a very basic activity that ensures people keep sipping their beer (it was also a very rudimentary form of beer pong). Some versions are played in teams, others with cards, some while watching television. Some are incredibly simple, some are abstruse. Some are played mainly for their social value, others are more brutalist activities to facilitate getting drunk fast. What follows is a sampling of some of the enduring favorites.

A team competition that requires plastic cups and an equal number of players (minimum six total). To play, the plastic cups are filled and distributed among the teams. One member on each team drinks his beer as quickly as possible. In boat races, the drinker puts the cup upside down on his head before the next team member can begin drinking. In flip cup, the drinker must put the vessel on the edge of table and flip the overhanging edge so the cup lands upside down on the table. Only then can the next member continue.

BEER PONG

In beer pong, another team event, six or ten plastic cups are arranged like bowling pins on either end of a longish table (often a ping-pong table—hence the name). Players throw ping-pong balls at the opposing glasses. If they land a ball in a cup, members of the other team have to drink the contents. There are many variations and house rules to beer pong.

BULLSHIT

There are many card games, but bullshit has both strategic and social elements, elevating it above some of the others. A deck of cards is distributed to participants. The first player discards all her aces, the second all her twos, and so on. The object of the game is to get rid of all your cards. One may lie and discard the wrong cards in an effort to win the game. However, if someone shouts “bullshit” and the player has lied, she must pick up the pile of discards and drink. If she was telling the truth, the accuser must pick up the pile and drink.

Shuffleboard originated in the pubs of England.

QUARTERS

The implements of this game are a quarter dollar and a shot glass. Players take turns trying to bounce the quarter off the table and into the glass. If successful, the shooter selects one of the other participants, who then must drink.

Drinking games are legion. The list gives a sense, but partisans for Master of the Thumb or Zoom Schwartz Profigliano will surely say it is incomplete. New games are born constantly, and perhaps you have invented your own. In the best of cases, they’re simple and fun and great as icebreakers. You might even give the old soccer-ball-and-laundry-basket game a go; I recommend a bouncy ball.

Who was the first man—it had to be a man—ever to say to his companion: “I can drink my beer faster than you”? Probably the man who invented beer. Feats of speed, constitution, and capacity are just human nature, so naturally, the beer world is littered with them. In the 1970s, Guinness World Records clocked Steven Petrosino drinking a liter—nearly 34 ounces—in 1.3 seconds. It seems gravity was his greatest obstacle. Englishman Eric Lean set a record for capacity in 2003 when he downed 7.75 imperial pints in five minutes. That’s more than an entire half-case to you Yanks. The late Andre the Giant once drank an astounding 119 twelve-ounce beers over the course of six hours. (Guinness has since discontinued record keeping on feats related to alcohol, an interesting irony given that it was the managing director of the eponymous brewery who started the whole thing.)

It goes without saying that these are unhealthy and in most cases dangerous practices. It also goes without saying that people know this and engage in them anyway. The allure of getting booze into the belly fast is as timeless as it is ubiquitous. When I was in my tender drinking years, we played quarters to while away our time; today beer pong dominates. There’s no point in going very deeply into these practices, except to note a few that have survived the centuries. They have achieved something like cultural acceptability and can do the standing-in for more disreputable practices like shot-gunning, boatracing, and beer-ponging, all of which are well documented across the Internet.

YARD OF ALE

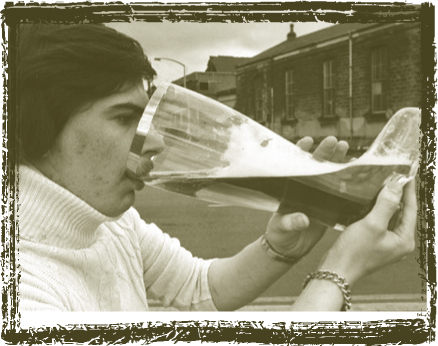

The name is admirably direct: An ale yard is a glass vessel, trumpet-ended on one side, fish-bowled on the other, that runs one yard’s length. The old chestnut holds that these devices were used to whet the whistles of thirsty Victorian coach drivers. Their length facilitated handing up to the driver, who apparently was so busy he didn’t have time to scramble down to drink a pint. Like so many of the tales we tell of the nineteenth century, it’s almost certainly not true—contemporary accounts of coach travel never mentioned them—and the yard was rather, as it is today, a test of one’s drinking mettle.

The notion is to drink the whole thing in one go. Part of the difficulty is volume; a yard contains around 50 ounces (more than three pints) of liquid. Part of it is technique. The devilish design, which narrows to a thumb’s width just before opening into a wide globe at the bottom, creates problems with air movement. As the liquid struggles past the narrows and into the globe, it dislodges a wave of beer, which douses the drinker—to the pleasure of everyone else in the bar. The trick is to go slowly and gradually spin the yard, which allows air to sneak in. That is, of course, if you can manage to drink two and a half imperial pints of ale without stopping.

BOOT OF BEER

Closely related to the yard is the beer boot or bierstiefel. Another vessel with a forthright name, this is a glass boot that usually contains two liters of tasty German lager. As with the yard, the origins of the boot are murky and they tend toward the unlikely. The more believable story is that they, like the yard, were part of drinking-game fun. There’s a potential booby trap for the first-time boot chugger, but it’s easier to overcome. The toe of the boot must not be facing skyward, or the vessel will burp in the same manner as a yard, sending a disgorgement of beer out and into the face of the drinker. If the toe points down until most of the beer is gone and then the drinker slowly rotates it to the horizontal position, gushing beer is no worry. ■

A challenger partakes in the time-honored tradition of chugging a boot of beer.

Alcoholism. By sheer numbers, alcohol is one of the most deadly substances on Earth. The World Health Organization estimates that it kills 2.5 million people a year and is the third largest risk factor for disease. In the United States, drunk drivers are responsible for over ten thousand deaths a year. Long-term alcohol abuse leads to a host of physical ailments and mental health problems. Alcohol abuse is the second leading cause of dementia. It has profoundly malign effects culturally, affecting far more than just the drinker; alcohol abuse leads to violence, child neglect and abuse, and accidents. One does not have to develop a moral paradigm to recognize the impact alcohol has on society.

That alcohol is a mind- and mood-affecting drug is one of the reasons humans consume it, but it comes with the further danger of addiction. Definitions for alcohol dependency vary by culture, but the phenomenon is obviously real—as are the withdrawal symptoms, which are so severe they may be fatal. Everyone enjoys the occasional merry evening, and even extreme behavior like drinking from a yard or boot can be fun and harmless. But it’s important to acknowledge that alcohol consumption has its dangers. These are all the more acute when the intention is focused on drunkenness.