Dark Lagers: Dunkel, Schwarzbier, and Czech Tmavé

Pale Lagers: Pilsner, Helles, and Dortmund Export

Amber Lagers: Märzen and Vienna Lager

What exactly is a lager beer? This question is, at its heart, an existential one: Is lager a final, objective state, or the process of becoming? By one definition, lagers are known by the type of yeast they use—one that enjoys cool temperatures and that tends to sink rather than rise. The other definition demands that the beer be conditioned or aged after primary fermentation. The German word lager, in fact, comes from the sense of “storing.”

In most cases, the distinction is purely academic; “lagers” are understood both to use a particular type of yeast and to have gone through a period of conditioning. Yet some ales are “lagered,” that is, brewed with ale yeast and then put down for a period of time. Around Cologne and Düsseldorf, brewers may refer to their beer as top-fermented lagers (obergäriges lagerbier). French bières de garde are routinely called “ales,” yet are conditioned for weeks or months—and in some cases even brewed with lager yeast strains. On the other hand, America’s most famous indigenous style swings the other way. “Steam beer” is brewed like an ale but with lager yeast. For the purposes of discussion, let’s ignore the oddballs. As they are broadly understood, lagers meet both definitions: They are made with a yeast strain that prefers cold temperatures and they are conditioned for a period of weeks or months.

What distinguishes lagers is less the way they’re manufactured than the way they taste (though of course one begets the other). Yeasts laboring in cool temperatures are less flamboyant than those found in warmer-temperature ales. The chill inhibits the production of esters and phenols, those compounds that taste like fruit and spice, leaving the beer’s basic ingredients to carry the day. When you sip lager, you’re experiencing the soft, wholesome flavor of the malts and the delicate spice of the hops without any filter or film. Cold fermentation leaves beers coarse and unfinished, but the period of conditioning sands away rough edges and exposes the rich grain of malt and hops. Lagers are refined, clean, and polished beers. Isn’t it wonderfully symmetrical that Germany would become the greatest champion of this new way of brewing? Absence of ornamentation, harmony between design and function—these describe Bauhaus architecture as well as lager brewing.

The remarkable story of lager begins around the late thirteenth century, as brewers began to intuit the presence of yeast. Until that time they fermented their beers spontaneously, but eventually they learned to skim yeast from actively fermenting beer to seed the next batch of wort—a practice mentioned first in a logbook from the mid-fourteenth century. Over the decades, brewers refined their process so that they later maintained stores of yeast. Even though it would be centuries before anyone discovered what the tiny cells were, brewers understood how to use them. By collecting the barm (yeast cake) and repitching it, they were, over time, very slowly domesticating brewers yeast.

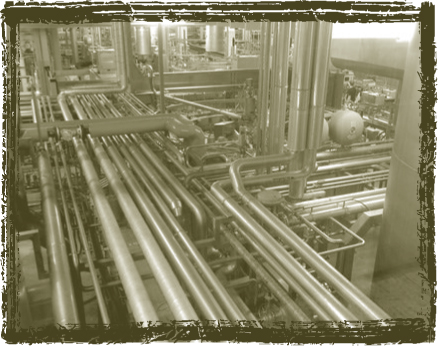

The biggest breweries in the world, like Munich’s Paulaner, have lager running through their veins.

In Bavaria (or possibly neighboring Bohemia) in the early 1500s, some of those yeasts started behaving strangely. Most of the yeasts preferred warmer temperatures, but one variety emerged that liked it cold. In fact, this strain settled out of suspension and refused to work well in the warmer months—when brewers had to return to the older, warm-weather yeast. These beers were the first lagers, and they were prized in the region. By 1539, the Bavarian government actually mandated that brewing only happen in the cool months when the favored yeast could work its magic. By the turn of the seventeenth century, brewers elsewhere had become aware of the two different strains. Outside of cooler Bavaria and Bohemia, though, lagers were hard to brew. In fact, the results were so bad that lager yeast was banned by the Cologne city council in 1603; England and Flanders were likewise too mild. So for hundreds of years, lager remained a local specialty limited in production to the cellaring caves of a small, southern region of the beer world.

It wasn’t until the nineteenth century that the golden age of lagers dawned. In the early 1840s, three brewers working in three different countries began experimenting with pale malts to produce sparkling golden-to-amber lagers: Anton Dreher in Vienna, Gabriel Sedlmayr in Munich, and Josef Groll (another Bavarian) in Pilsen (Plzeň), Bohemia. Two decades later, Louis Pasteur finally revealed the science behind yeast. (He strongly recommended lagering to improve purity). And finally, by the 1870s, refrigeration made it possible to start brewing lagers in warmer climates.

The effect was profound—if slow to develop. Two decades after Groll started brewing pilsner, there were still more than twice as many Bohemian breweries making ale as lager. But by 1875, almost the entire country had flipped—of 849 breweries there, 831 were making lagers. In Germany, the change took a bit longer. By 1870, the vast majority of breweries were still making ales, but the lager breweries were growing and had already eclipsed ale production. By the turn of the century, lagers had seized more than 80 percent of the market and were still growing. That proved to be a harbinger of trends across the globe. Although there are still more styles of ales than lagers, the battle for hegemony is long over—lagers make up more than 95 percent of the world’s beer production (and the vast majority of those are pale lagers). A hundred and fifty years ago, the percentages were just the opposite. ■