2. H a Section

remembering . . .

spilling the peanuts my father bought

all down the aisle of the train,

1954, or dad yelling at me, 1948,

because I was running back & forth to the water cooler

— bpNichol in Continental Trance, 16

I knew that ‘H’ comes after ‘G’ and that ‘I’ was next, so that if I was at ‘I’ I had gone too far.

— Nichol in Multineddu

“An Interview with bpNichol

in Torino, May 6 & 8, 1987,” 34

In the spring of 1948 Glen Nichol was transferred by the railway to Winnipeg where he unexpectedly and unwittingly gave his son Barrie a gift that he would increasingly treasure. Glen bought a newly built house in the south of the city near the west bank of the Red River. It was not, on the surface, the most practical of gifts. Given the likelihood of his being transferred, the Nichols would usually rent their accommodations. Moreover the spring of 1948 had been one of worst periods of serious flooding along the Red. Glen’s chosen house was part of a novel experimental residential development, Wildwood Park,1 built on a series of paved looping laneways within a sharp bend of the river. The fronts of the houses faced each other across unfenced parkland — their own village green — with the rear or service entrances facing narrow laneways. There were sidewalks across the fronts but none along the lanes. The plan was intended by the designer to encourage a village-like sense of community. Each laneway loop was called a “section” and named alphabetically. The Nichols’ new house was in Section H.

Glen actually did intend the house as a gift — as a surprise for Avis. He was apparently not on the 1948 train on which Barrie recalls, in Continental Trance, being chastised for too frequently running to the water fountain, but had gone to Winnipeg in advance to find and set up the new home. In a 1972 draft of “The Autobiography of Phillip Workman by bpNichol,” written 10 years before Continental Trance, it was Barrie’s mother who accompanied his siblings and him from Vancouver to their new Winnipeg home, and who angered him by making him stop dumping paper cupfuls of water into the fountain and watching them disappear. Having told her and the children almost nothing about their new home, Glen Nichol picked them up at the Winnipeg CN rail station and drove them directly to it. Avis was delighted — like many in the postwar period she was entranced by “the new.” A new house, with new furniture and appliances in an ultramodern subdivision, was much better than she had hoped for. The one-and-a-half-storey house had three bedrooms, one of which was shared by Bob and Don, and another by Deanna and Barrie.

Despite the hundreds of drawings, cartoons, and visual poems based on the letter H that Barrie would go on to create, and Avis’s pleasure in her ultramodern surroundings, the family’s years in Wildwood Park would not be especially happy. As at each new move, the children’s schooling and friendships had been disrupted. Avis also had to develop new friendships and was now far from relatives. She was also far from shopping areas and unable to drive. A neighbourhood friend would sometimes offer a ride, but often Avis would have to go by bus to buy groceries and take a taxi back home.

For young Barrie, however, the most important aspect of Wildwood Park would be how it was making intensely physical his encounters with language. Those alphabetically named streets would render the alphabet non-transparent for him — making each letter a recurrently self-referential sign. While most people routinely “see through” the letters of words to the sound or idea or object to which their culture has agreed that they refer, for Barrie those letters would also be tangible material things in themselves. “So when I was first learning to find my way home to H-section,” he will tell an interviewer in 1987, “I was also learning to find my way through the alphabet. I knew that ‘H’ comes after ‘G’ and that ‘I’ was next, so that if I was at ‘I’ I had gone too far.” He continued, “I was always very aware of letters, and so on, and of the ‘S’ at ‘house.’ . . . I’ve always had a kind of, I suppose, idiosyncratic, very particular relationship to the idea of the alphabet, the idea of language” (Multineddu 34). In fact he would come to regard alphabetic characters as designs, or pieces of visual sculpture, or visual drama — ‘H’ as the linking of an ‘I’ and an ‘I’ — far beyond their conventional roles as signs for phonemes or building blocks for words and sentences.

Wildwood, with its spacious common parklands, would also be for many years the most rural of Barrie’s homes, the one with the most plant and animal life, the one where it was easiest to watch clouds. What made it isolating for his mother would make it a place of solitary and complex imaginings for him. It would be the probable inspiration for the images of “Cloudtown” in his continuing poem The Martyrology, and for those images of lost pastoral gardens there and in his other early works. Barrie/bpNichol would claim so in The Martyrology, Book 5, Chain 9, saying of his “saints”

. . . i saw these same faces

early in my first phrase’s speaking

(age 6) summer mornings i’d escape

before my family’d awake

H section Wildwood Park

singing my heart

straight up at that Winnipeg prairie sky

at you Lord

at the saints i knew lived there

leaving my head till 16

one day

looked up at that cloud range

a kind of joy took me

perception you were all still there

if only i could once again sing to you.

It may have taken him a while to “again sing,” for there is no surviving textual evidence that Barrie wrote of saints in 1960–61 when he was 16, or before 1965 when he begins writing the early sequences of Scraptures. However, in a 1974 interview he provided a more detailed and plausible account of the saints’ early childhood origin. “And the saints! I mean the saints essentially came out of that whole perception of when I was a kid and thought that real people lived up in the clouds.”

I looked up between the clouds. I always thought it was like the edges of a lake and that we were living at the bottom of the ocean and the real folks were up there. That’s where I thought we were going to go someday. Heaven. I always thought heaven was the clouds, because those are the drawings you get: in the United Church you get a little Sunday school paper and everybody’s walking around on clouds. (“Interview: with Pierre Coupey et al,” Miki 2002 149)

He would give Flavio Multineddu a similar explanation in a 1987 interview:

. . . as a little kid I had a whole fantasy world up in the clouds: that people lived up there and they were watching us all the time. This was my child imagination of God: that God lived up there and that the devil lived down in the ground, and I had this feeling of these eyes looking down over the edges of clouds. (19)

Here at Wildwood was indeed where Barrie experienced his first formal instructions in theology. He and Deanna attended a nearby United Church Sunday school because the Presbyterian church was much further away.

I was raised Presbyterian with lots of time in the United Church because there weren’t that many Presbyterian churches around and because my parents both loved to golf on Sundays and therefore did not really have a strong case for pushing me to church, though they felt guilty. [. . .] I grew up with Sunday school comics in which great sweating Corinthians battled I can’t remember who, but it was all done like Superhero comics, and heaven was a place of clouds and of people in funny white robes. (“Talking About the Sacred in Writing,” Miki 2002 335)

There is considerable irony here in Barrie’s absorbing theological imagery from comic books provided by the United Church — a church created in a 1925 merging of Methodists, Congregationalists, and Presbyterians — when in the English 17th century Presbyterians often led the mobs of “iconoclasts” who destroyed the medieval statues and stained glass portraits of saints at almost every English cathedral. And there’s a little additional irony in that stained glass often being described by historians as the precursor of modern religious comic books.2

At Wildwood Park, Barrie also learned from his mother a version of the once commonplace child’s prayer, which he recorded in a 1971 notebook as Part 9 of “The Book of Oz,” and later included, with small changes, in The Martyrology, Book 3.

‘God bless mother & father

dj bob & dea

grandma & grandma

all my cousins aunts & uncles

all my friends

all the plants & animals

forever & ever

amen’

But except for the compilers of the four gospels, Barrie would have been unlikely to have heard mention of the specific word “saint” in either the United Church or in his Presbyterian-descended family. However, the valley of the Red River did harbour quite a few saints — the settlements of St. Anne, St. Clements, St. Paul, St. Boniface, and St. Pierre, as well as the potentially blessed Stonewall and Steinbach. In The Martyrology, Book 5, Chain 3, Barrie recalled one of these —

H origins

remembered names

Fort Rouge

St Boniface

he of the happy face

eternal smile

saints that were there

over the river in

my childhood

the presbyterian boy who

eschewed the ritual view

However, any “happy face” images young Barrie may have been developing of an Oz-like parkland sparkling beneath an ever-changing heavenly Cloudtown were soon to be drastically interrupted. By late March 1950 it was evident that the melting of heavy winter snows was threatening to overwhelm the dikes along the Red River. Massive efforts to repair and strengthen those dikes and add walls of sandbags began and continued through April. But by May 11, eight of the dikes protecting Winnipeg had failed, one-quarter of the city had been submerged, and around 100,000 people had been evacuated — the largest Canadian evacuation to that date. At its bend in the river, Wildwood Park was one of the most vulnerable areas. In late April seepage through the dikes had already flooded the common lawns. The yards of many of the houses had become worksites for crews fighting the rising waters. In his 1972 draft of “An Autobiography of Phillip Workman by bpNichol” (“Notebook III”) Barrie detailed a 1949–50 winter of much snow followed by intense spring rains and the Red River steadily rising. He described himself standing on a dike that workmen were building amid continuing rain and river seepage. Some houses closer to the river, he wrote, had already been evacuated, and he figured their house was next. He added that they would leave three days later for Calgary and be gone for six months, and that while they were gone someone would place a wooden donkey in the window of a second-storey room that the waters rose to. The account shows again how directly autobiographical his “Phillip Workman” narrative can be. On May 11, the Wildwood dike was the first Winnipeg dike to fail, and by the end the day most of the Park’s houses were flooded up to their eaves, with their sheds and garages floating free.

WILDWOOD PARK, MANITOBA, AT THE PEAK OF THE 1950 FLOOD.

The Nichols, however, did not all go to Calgary, nor did any go directly there. Glen remained at his job in Winnipeg; Bob, the rowdy and adventurous son, went to one of Avis’s uncles’ farms in Plunkett, Saskatchewan; Avis took Don, Deanna, and Barrie to stay with her sister and her family in Saskatoon. Her brother Bill in Regina, however, insisted that they would be more comfortable with him, his wife Ethel, and their two young daughters, who lived in a spacious Quonset hut. So after a short and pleasant stay in Saskatoon, Avis and the three children moved on. But in Regina, Avis soon became unhappy, and resolved to continue onward to Calgary where they could stay with Glen’s mother. She explained later to Deanna that — prevented from doing housework, which she found pleasure in — she had been bored, and that also her brother’s quiet young girls and her own children did not get along. But she herself was also not getting along with Ethel who appeared unhappy to be hosting them.

In a 1971 draft of a text titled “Plains Poems” — much of which he included in The Martyrology, Book 3 — Barrie recorded a more poetic, but Oedipally troubled, memory of that journey. Its metaphor was part of the “i wish i had a ship would carry me” metaphor of Book 3, Part V. In the draft he wrote that one is one’s ship, forever seeking harbour or hoping to return “home” while the aurora borealis shimmers and the river, the red river, flows and rises against its dikes. He is abruptly a small boy of six watching in the rain while the river rises and men stack sandbags. He writes of Okeanos seeming angered, going by boat from his home, fleeing Lethe and the Styx, and travelling by train to Calgary where it was also raining, and of wanting someone, a “you,” to make love to him. Okeanos as the angry father, and his mother as the boy’s desired “harbour,” seem almost too predictable — which may be why the passage did not survive his editing.

It was not until August that the Nichols were all able to reunite at Wildwood. The house had needed extensive repairs. The furniture and appliances of the first floor and basement had to be removed and replaced. The yard and parkland had been littered with debris, including the corpses of livestock that had been drowned on the farms to the south, and had had to be cleaned and restored. Once again, Glen Nichol had a “new” house and furnishings ready for his family when they arrived at the Winnipeg rail station. But in less than two years, the Canadian National Railway again moved him to another location.

In these two years one hugely formative event befell Barrie. It was his chance visiting of another child and encountering a Dick Tracy comic strip. He wrote his fullest narrative of this encounter in his April 1972 draft of “The Autobiography of Phillip Workman by bpNichol,” Part II, Section IV. It’s a section that is seemingly more carefully written, and more literary, than most and is framed as a message by Phillip to his mother. But considering that Nichol’s collection of Dick Tracy comics would, by his death, fill a small room, its various specifics — the visit, the rain, the Dick Tracy images, the feelings of being lost in darkness — seem very likely accurate. In the voice of a mature adult looking back at a troubled childhood, he wrote that it was because of encountering the Dick Tracy comic strip that he came to choose, at six years of age, to withdraw psychologically from the “noise” of his life with his family that he could not respond to.

On a rainy day he had gone to make a first visit to a new friend. The friend showed him a book of Tracy comic strips; in one Tracy and his dog crawled into a dark sewer pipe in which Junior had become lost. Barrie wrote that this story was becoming difficult to write because he had identified with that lost boy, that he too had felt lost in darkness. He had been amazed and thrilled to think that there could be someone who might try to rescue a boy like him when no one else would. He had found himself loving Dick Tracy. Later in Port Arthur, he wrote, his fixation on the yellow-hatted Dick Tracy had become even clearer and more memorable. You have to do whatever you can, he commented, to make your life endurable, if you have a desire to live.

What this passage appears to recall is Barrie Nichol’s very first turn outward from his family — outward, but not necessarily away — and toward at least two basic elements of his adulthood. The most obvious element is the comic strip, which would later become not only a room-sized collection but one of a number of narrative solutions he would frequently deploy, and the most likely basis of his visual poetry. The second is the determination expressed to do whatever you can to make your life endurable. It’s a determination that would see him make decisive and sharp life changes, and become increasingly creative and productive — all the way to September 1988. Notable also are various expressions of agency that appear new to his memories: that he chose to withdraw from his family, that he identified with Junior, that he loved. As well, there is a positively perceived male figure — possibly the first of his imagination. Some fragments from this passage recur in The Martyrology, Book 3, “Interlude: The Book of OZ”:

i remember winter nights in my room

the bed dj & i shared

i had a friend

torn as he was from the funny papers

crazy jutting jaw stupid yellow hat

i talked with him.3

There was also in these last two years in H section of Wildwood a smaller but similarly significant development for Barrie. Deanna recalls that her bedroom companion began composing oral stories, mostly fantasy adventures, and narrating them to her before they fell asleep. Their mother regularly sent them to bed at 7 p.m., ensuring quiet for Glen and less work for herself, but leaving Barrie and Deanna with much time to fill. One of the stories he called “The Little Man with the Big Head who Came over the Hill.” Much later Deanna would remind him of it, and he would make a cartoon of the little man for one of her young children. But these oral stories soon came to an end. Early in 1953 oldest brother Bob left home and joined the Canadian navy; the family would not see him again until 1965. The parents moved Barrie into Bob’s old space in the room he had shared with Don. Scholarly in contrast to Bob’s angry rebelliousness, Don had never gotten along well with Bob, and had privately seen himself as the more suited to the role of elder brother. He was much happier to have Barrie as his roommate. With Bob he had been an unhappy rival, with Barrie he could be cheerful mentor. Still sent to bed at 7 p.m., Barrie impressed his new roommate not by improvising oral stories but by taking a dictionary to bed so that he could acquire new words before sleeping.

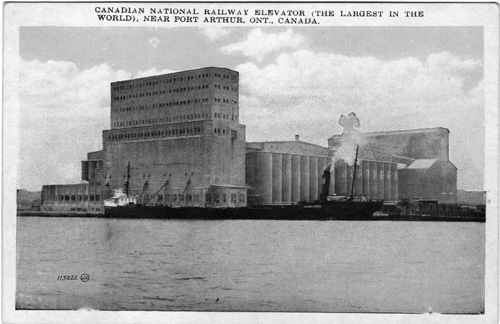

CANADIAN NATIONAL RAILWAY’S GRAIN ELEVATORS IN PORT ARTHUR, ONTARIO — THE LARGEST IN THE WORLD IN THE 1920S.