11. Beginning The Martyrology

The ‘i’ is me and it isn’t me. The ‘i’ is a construct of autobiographical elements; imagined moments which have taken on realities as well. There’s certainly autobiographical detail in The Martyrology, but it’s not there so much to track autobiography as to elucidate the moment of the writing.

— bpNichol in Niechoda, A Sourcery, 178

Barrie’s return in 1966 to writing “regular” poems had been enabled less by psychoanalytic insights — most of which were still to come — than by what he had learned by writing ideopomes — that a poem could be a visual object that interacted with, and in a sense incorporated, the field of its page, rather than a script for the “arrogant” declaration of emotions or ideas. The ideopome’s components could be words, syllables, letters, drawings, and blank space; the relationships among these could be investigated and elaborated by the poet. In that investigation, however, there were indeed hints of psychoanalytic activity — as he had written to Shives, his ideopomes could show the mind how to bridge gaps, to not fear the unexpected, and to see beneath the surface appearance of things. Suspicious reading of a text, image, or event — that its “surface” meaning might not be its only meaning — had been one of Freud’s earliest discoveries.

This return, however, was largely also to poems that had originally been written in his “arrogant” period. It had been to those poems from 1963 to 1964 that he had hurriedly rewritten in order to have something to offer to Souster’s New Wave Canada. The poems of “Journeying and the Returns” included in the bp box and written from 1963 to 1966 were similar — lyric poems that reported being sensitively “inside” particular situations and experiences, but were linked into six sequences, the longest composed of seven sections. Barrie’s expressions of unease to bissett following the publication of bp — that he was sick of the poems he was currently writing — suggest that his return to discursive poetry was not always a happy one. His next collection of “regular” poems was The Other Side of the Room, written 1966–69 and published in 1971. These were mostly one-page lyrics, many of them untitled. Many of them were plaints, such as the untitled one that begins:

If there is one I’ve sought

who is she

who is not

the ones I’ve found

never in my life

I’ve known peace

seldom can I hear see

clearly (20)

But there were also several dedicated or addressed to various friends — to Phyllis Webb, Victor Coleman and his first wife Sarah Miller, to artist and curator Dennis Reid and his wife Kog, to David Phillips and his first wife Denise. These poems implied dialogue and “communication,” a key word in Barrie’s early therapy years, and foreshadowed other dedicated poems he would write. However, The Other Side of the Room is a book that Barrie would rarely talk about in his interviews, or mention when later classifying his books as “failed,” or “dead,” or “living” and therefore possibly worthy of revision or reissue.

Barrie had worked or begun work on numerous projects in the 1965–68 period: The Captain Poetry Poems; “The Journey”; “Journeying and the Returns”; The Other Side of the Room; the novel “For Jesus Lunatick”; the Nichol family poems “The Plunkett Papers”; Scraptures; the long poem “Land”; a two-part work titled “Lungwage: a domesday book”; and a Hamlet-alluding long poem “The Undiscovered Country.” He had also been working on ideopome ideas that eventually became Still Water and ABC: The Aleph Beth Book. Even at this time, however, he was apparently thinking that most of these might be part of a single work, or that someday he would have the “intelligence” to see how most of them fitted together, much as how in The Captain Poetry Poems he had found a way to combine ideopoem, comic strip, prose, and “regular” poetry. He suspected that many of the very early writings that he now regarded as failures might actually belong to a collection he could conceive of as “The Books of the Dead” and the later writing to another collection “The Books of the Living” — which he might be able to combine someday into a single book. In February 1979, while attempting to map a new direction for The Martyrology, he wrote in his “The Encounters” notebook that he was thinking back to his late 1960s idea of splitting his writing into “The Books of the Dead” and “The Books of the Living.” He remarked that back then he had believed that his work would soon change, that he would soon be reborn, “completely” born this time, with an intelligence he had previously lacked, and that he had hoped to find a structure that could contain both this new work and his earlier failures, such as “The Journey” and “The Undiscovered Country,” both of which, he thought, would have benefitted from his later discovery of the utanikki, the traditional Japanese poetic travel-diary.

Barrie was recalling here a causal link in the late 1960s between his growing command of poetics and literary structure and his being reborn into the world through his therapy. His psychoanalytic thinking had been giving him the conviction that his current writing would eventually be part of larger things that he was not yet capable of conceiving or creating. The “Books of the Dead” were books attempted while he was suffering from recurrent depressions and in which he sentimentalized and “romanticized my experience to a disgusting degree” (Miki 2002 234) — but he still hoped somehow to save them as early parts of an evolved life’s work. The “Books of the Living” were to be ones in which he had become able to see beyond self-preoccupation to rhythms and insights his own writing was proposing.

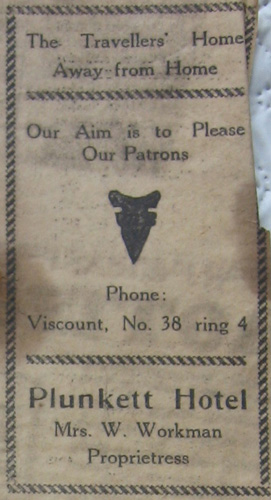

Irene Niechoda outlines how in 1965 his personal research into various non-Western creation myths had led him to consider creating his own creation story for his Cloudtown and its saints, and to — perhaps playfully — place this Cloudtown slightly west of Wildwood Park in one of the sites of his own creation, the small farming town of Plunkett, Saskatchewan (1992 20–22). This is where members of his mother’s Workman and Leigh families had farmed, where the Workmans had operated the Plunkett Hotel, and where her parents were living when his father had encountered her. The majority of “The Plunkett Papers” was written 1967–71, a few pieces of which Barrie printed in 1980 in the chapbook Familiar for distribution to friends, and a few more Niechoda herself published in A Sourcery as a possible aid to understanding The Martyrology. Barrie’s mostly unpublished “The Plunkett Papers” presented Plunkett as the realm of the creator “Cloud-hidden” and a “ground where the saints walked.” Niechoda writes: “All the major saints, as well as Captain Poetry and Billy the Kid, visited Plunkett. (In one passage St And mourns the death of the latter)” (1992 22). Barrie’s controversially award-winning chapbook, The True Eventual Story of Billy the Kid (1970) was written in 1967 either as a possible part of “The Plunkett Papers” or in association with them.

A 1929 ADVERTISEMENT FOR THE WORKMAN FAMILY’S PLUNKETT HOTEL, PLUNKETT, SASKATCHEWAN.

In the summer of 1969 he and Rob Hindley-Smith drove slowly from Toronto to Vancouver through Port Arthur, Winnipeg, and Plunkett, taking photographs of various Nichol family buildings as they went, including the Plunkett Hotel. Very likely this was at least in a part a research trip for “The Plunkett Papers” — as well as a personal pilgrimage. While they were in Plunkett, Barrie drafted in his notebook that poem’s mythologized version of his parents’ meeting and his own coming into being. In the poem he translated their names: Avis, he wrote, means “free” in French, and marries Glen whose name in Scottish is a small forested valley, becoming one who once “was” free, and later bearing as her third son someone who sings songs, who some predict will be a “simpleton.” Later that summer Barrie recorded in the same notebook genealogical information about the Leigh, Workman, Fuller, and Nichol families for use in this Plunkett project, on pages adjacent to ones on which he was drafting The Martyrology I’s “The Sorrows of Saint Orm.”

In an obvious revision and expansion of his 1979 notebook entry about having once hoped to write a combined “The Books of the Dead” and “The Books of the Living,” Barrie wrote in a 1979 note for Michael Ondaatje’s The Long Poem Anthology that “somewhere in my 20s” he had begun “to think of this [my poetry] as one long work divided (roughly) into two sections: The Books of the Dead & The Books of the Living. [. . . .] The problem was I couldn’t make it work.”

So in 1967 he had “temporarily abandoned this notion” and “began work on The Martyrology” (335), a book-length poem in which he could expand on the saints he had recently discovered in Scraptures, and revisit, re-envision, and attempt to understand many of the childhood fantasies that had begun the morning in Wildwood Park when he had seen a “cloud town” floating above him. In a sense, The Martyrology began as a recombinant work written as a substitute for the much more combinant and unifying books of dead and living whose construction he was now postponing. At the same time he also began the poem sequence to be published in 1971 as Monotones — seeing it, however, as a yet formally unplaceable part of the new Martyrology project. That sequence would be the first of his “regular” poetry books to be published as a single book-length work. He was now working on three Martyrology-like projects concurrently but without an understanding of their interrelationships — Book I of The Martyrology, Monotones, and “The Plunkett Papers.”

Monotones, written mostly 1968–70, can be precisely dated by its title and photographs by Andy Phillips. It was written during the first years of the Therafields farm at Mono Mills. Barrie’s new duties as Therafields vice president, which also included being custodian of the farm tool room, saw him spending many days there as the barn and other buildings were renovated to create dormitories, a dining area, and a meeting space. Fields were planted, and the site overall was prepared for the hosting of therapy groups. Phillips’s photos — printed by Talonbooks in a sepia “monotone” — show the barn and a lush field on the cover, and on the frontispiece Barrie and Therafields financial officer Renwick (“Rik”) Day amid the barn renovation. Most of the sections have little intense personal content; instead they address Barrie’s daily life when on the farm, and at times express gratitude for the friends and experiences his farm responsibilities are giving him. It is a work that is close to being a journal — unlike his short lyrics, which are mostly about occasional thoughts and moments — and is quite unlike the other texts Barrie was writing and believing to be part of the new Martyrology. Noticing this difference, and being unable to write his way past it, Barrie severed the two works sometime in 1970. Ironically, some of the later books of The Martyrology would have a striking resemblance to the journal-like Monotones. In fact he would tell Niechoda in her July 1987 interview that he now realized that in 1968 he had unwittingly had something of a single work in his grasp and been unable to see it, that Scraptures had taken “two branches, but I didn’t have the sophistication as a writer at that time to understand that.” He felt that “Monotones has to go back and have its place restored.” He told her that it was his conviction that The Martyrology was to be “processual” (i.e. that it had to follow the sequence of his consciousness while he was composing it) that had caused him to overlook the possibility that he could be writing three concurrent parts of the same text and in each one employing different composition techniques (1992 31).

But Barrie’s other limitation at this time was that he saw The Martyrology only in terms of saints and superheroes — only as a text in which to think through once again his Wildwood Park and subsequent fantasies, and the years of evolution and elaboration he had given them while experiencing himself as the companion of super detectives, superheroes, and science-fiction adventurers. Moreover, he appears to have viewed these fantasies, at least initially, as not merely his creations or personal mythologies, but as products also of contemporary culture and therefore as the potential basis for a culturally relevant processual long poem. Midway through writing the first two books, in April 1969, he wrote in that “Comics as Myth” entry in his notebook “these saints [of the Martyrology] grew out of a Sci-Fi comic strip milieu. And that is what The Martyrology is or means. The relevance of myth is only as you make it relevant to your own time” (Peters 81). He went on to tell himself that to apply classical mythology in contemporary writing “seems such a useless thing” (84). Barrie’s now almost two decades of fantasies — people in clouds, Dick Tracy in Port Arthur, Bob de Cat in Winnipeg who evolved later into Captain Poetry, Yaboo, and Blossom Tight — were of course also, as his preferred childhood escapes from his unhappy family life, material for his therapy work and for a kind of psychic autobiography. By being able to create written stories and comic strips from his Bob de Cat, Sailor from Mars, and other daydreams, Barrie had, from roughly 1954 on, been reaping what Freud called “gain from illness” or “secondary gains” — from persisting in fantasy at the expense of deeper engagement in soccer games, teaching, or social relationships. In a sense these gains were “free,” already created, poetic materials initially created not as literature but as the “primary gain” — defence against darker thoughts, including suicide. Was the new poem a sign of resistance to his therapy? His remarks to Niechoda about the temptation to take similar material to his poems rather than to his therapy and how in therapy he learned to ask himself “Was this really happening or was it my imagination?” (1992 135) suggest that he knew such was a possibility.

The most immediate formal starting point for The Martyrology and “The Plunkett Papers” was undoubtedly Scraptures, that series of visual and text poems Barrie had begun in 1965, during his self-imposed “ideopome” focus, and which he had published intermittently over the next few years mainly as grOnk pamphlets. Like The Martyrology, the title “Scraptures” owed something to the distinctly Catholic milieu in which he was then living — the many priests, monks, and nuns of Lea’s first house groups and learning group. “Scraptures” was a resonant and multi-layered word, hinting of rapture, scripture, and the scraps and words and images of which the series was composed — scriptures for experimental poetry. Nichol described Scraptures to Ken Norris as the first work in which he “cross-pollinated . . . started working between forms.” It began with a visual poem based on the first sentence of the Bible, then “I began to get into prose sections and I got into comic strip oriented sections, two of the sections are done as sound poems, though there are visual versions of those two as well” (Miki 2002 239). It was in the fourth of this series that Barrie and his library co-worker David Aylward discovered the “saints” within language, beginning with “St Ranglehold.”

That was about 1965 or ’66, and that’s sort of where it ended for David, but I began to see these “st” words as saints. Then I found that I began to address them — and I literally mean that I found, I was not expecting this. I began to address these pretty rabid rhetorical pieces to the saints in Scraptures. I realized that these saints had, for me, taken on a meaning and a life. . . . (“Syntax,” Miki 2002 273–74)

Their “life” was a new chapter in Barrie’s ongoing fantasy, something that Barrie makes abundantly clear when he begins The Martyrology with the science fiction preface “The Chronicles of Knarn,” or in 1969 when he writes in his “Comics as Myth” notebook entry about contemporary and classical mythology that “lately I find myself attempting to tie them all together — Bob de Cat, St. Reat, Captain Poetry, St. And, Bars Barfleet, St. Ranglehold, Yaboo & Blossom Tight” (Peters 84–85).1

Barrie had learned of the concept of a martyrology the year before from Julia Keeler, a former nun, whom he had met while working at the Sigmund Samuel Library, and who would soon also be a member of the Therafields community with a study at 55 Admiral next door to where Barrie was living. Keeler had been working on a doctoral thesis on the minor religious poets of the English 1590s and shared with him some lines from a poem “The Martyrology of the Female Saints.” From her Barrie came to understand that a martyrology was “a book in which you wrote out the history of the saints” (Niechoda 1992 63). And Barrie himself indeed had saints, discovered with Aylward while he was writing Scraptures — Barrie’s “saints were language, or,” as he told his interviewers in “Syntax Equals Body Structure,” “were my encounter with language.” And because of this, he suggested — with rather obscure logic — “the possibility of the journal form or the utanikki form also opened up” (Miki 2002 275). Niechoda notes that Barrie did not know about the utanikki form while writing The Martyrology, Book I and Book II, and did not consciously try to use it until writing The Martyrology, Book 4 in 1975 (1992 169). As well, Book I of The Martyrology often seems less a journal than a narrative history of Cloudtown interspersed with often painful lyric responses — although it can also be read as a journal of those responses.

Saints are holy figures who are martyred — unjustly killed for their beliefs and commitments. Barrie’s writing at this time has been filled with such thoughts of death — from thoughts of wandering into traffic at despair over Dace, to beliefs that most of his poems belong to “The Book of the Dead,” to announcements in ABC: The Aleph-Beth Book that “the poem is dead,” to the anguished lines in Nights on Prose Mountain (Scraptures 8, 1969):

NOW THIS IS THE DEATH OF POETRY. i have sat up all night to write you this — the poem is dying is dying — no — i have already said the poem is dead — dead beyond hope beyond recall — dead dead dead

Amidst his own recurring depressions and quick successes with his ideopomes, Barrie appears to have begun The Martyrology believing precisely this — that poetry as Western civilization has known it is either dead or in danger of imminent dying. Only by exploring how it has died, and by accepting that it is dead, is it possible, as in ABC, that “the poem may live again.” Later, when The Martyrology has both lived and evolved from his preoccupation with language saints, he will think of the title as “downbeat” but still “accurate” (Miki 2002 275) — but most likely “accurate” for different reasons. Metaphorically the looming destruction of Knarn in “The Chronicles of Knarn” at the opening of The Martyrology, Book I and the dispersion of the “saints” can stand in for this death of poetry and the exile of its poets. In Barrie’s early reading, the archetype for these was Superman’s exile from the destroyed planet Krypton. But of course Krypton’s story echoed much older stories of loss and origin — the story of Troy’s destruction and Aeneas’s wanderings before founding Rome, the story of Jerusalem’s destruction and its people’s subsequent communal wanderings, and the much older story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Eden. Much of this had been epic literary material. For Barrie personally, Krypton seems to have echoed the loss of his Wildwood, Port Arthur, and Winnipeg homes, and the slow death of both his life-suffocating fantasies of Cloudtown and of his private Jerusalem, Plunkett, Saskatchewan. Plunkett was for him his family’s point of origin in Canada, from where his mother had begun as hotel-owner’s daughter and become a reluctant wanderer among Canadian cities, none of them Plunkett. Barrie would repeatedly return to both Cloudtown and Plunkett, as both visitor and writer, seeking possible Martyrology material, as if they were sainted and originary sites.