14. Expository Turns

Continue continuously. Give the text the reality of its existence as an object & let that object be continuously present to you — timeless in that sense.

— bpNichol, “When the Time Came” in Miki,

Meanwhile: The Critical Writings of bpNichol, 319

My note of September 12, 1970, asking Barrie to meet with me currently rests in his fonds at the Simon Fraser University Library’s Special Collections. I was puzzled about what to write about Birney’s numerous visual poems. I’d written to Barrie four years earlier that visual poetry had never interested me. Now I hoped to talk with him and learn something about visual poetry’s theory and history, and perhaps how to read it. I was thinking of him as Mr. Canadian Concrete Poetry, Captain Concrete, the Concrete Chef, Captain Cosmic, or that enigmatic visual poem “bp.” He suggested we meet for lunch. What I gathered most from that meeting was a distinction between “clean” and “dirty” concrete — terms that I learned later were probably original with him. Stephen Scobie had implied as much in a June 1968 letter that he’d written after another conversation in which Barrie had used them. He was sending Barrie some of his own visual poems.

You’ll note differences between my work and a lot of the stuff you publish in Gronk — it is I think what you called the difference between “clean” and “dirty” concrete. I see the interest in dirty concrete but I prefer clean. Actually I’ve become interested lately in the number of different ways people sub-classify concrete. There does seem to be a definite split in method. Mary Ellen Solt and Mike Weaver use the division “expressionist v constructivist”, and you’re presumably familiar with Finlay’s “fauve & suprematist”. [. . .] These 3 divisions — clean, constructivist, suprematist / dirty, expressionist, fauve — don’t quite correspond but they come close to it. But the Canadians, especially Bissett, of course, are dirty. You mix the two, but I sense you are more at home in the dirty stuff.

In my book about Birney I wrote — after my chat with Barrie:

In clean concrete, the preferred and dominant type, the visual shape of the work is primary, linguistic signs secondary. In this view the most effective concrete poems are those with an immediate and arresting visual effect which is made more profound by the linguistic elements used in the poem’s constituent parts. The weakest are dirty concrete, those with amorphous visual shape and complex and involute arrangements of the linguistic elements. (1971 63)

I evidently would have disagreed with Scobie about Barrie’s work and viewed it as mostly “clean.”

Also in the Simon Fraser bpNichol fonds are files of 1967–76 letters from the British literary and cultural critic Nicholas Zurbrugg, with whom Barrie in 1968 had been having a lengthy dialogue about increasing conflicts among international concrete poets concerning what can be permitted to be called “concrete” poetry. Zurbrugg, who at 21 was about to begin a doctorate at St. John’s College at Oxford, favoured what he called “the purist movement,” which Barrie had evidently been questioning in his letters as a “great error.” Zurbrugg wanted concrete to be only “an extension of poets’s work,” favouring “a puritanical respect for the ‘poetry’ in ‘concrete poetry,’” and was “hesitant to accept signs by nonpoets — letter pictures” — i.e. he didn’t seem to want the work of non-writer visual artists to be considered “concrete.” He wanted “space and words and type (if possible) all with deliberate care selected to form a new whole a typographic minimal semantic poem . . . word and type should have equal value” (June 4, 1968). Barrie appears to have resisted such rigid definition, and slyly teased Zurbrugg with the question “wots poet tree.” The latter’s concern that concrete should be something “purely” created by writers only rather than visual artists, seemed to presume that one was unlikely to be both — as Barrie tended to be. His belief that its elements should be “word and type,” rather than word and visual design, also suggested that his “pure” had much in common with Barrie’s “dirty” in that both assumed a concrete poem was to be read at least as much as viewed. Zurbrugg — who as well as aiming at an academic career was working toward founding the magazine of concrete poetry, Stereo Headphones — also seemed concerned by recent remarks by various French concrete poets — “julian blaine jean francois bory jochen gers . . . are crying the death and sad obsolete state of concrete” and are “using photos etc integrated (?) in their works” (September 11, 1968). “I’ve been writing french to surprisingly a lot of french poets who say concrete is obsolete poetry / is sad obsolete there’s only the action of reader / and proposal of writer . . .” (November 12, 1968). The near-revolution of the previous May had of course politicized the contexts of much French art.

It is against this background of intense European debate about the nature and possible “death” of concrete poetry that Barrie not only speaks to Scobie and myself in those awkwardly metaphoric terms of “clean” and “dirty” concrete but writes the “poetry being at a dead-end” passages of ABC: The Aleph Beth Book, which he would publish in 1971 — and which Zurbrugg would ask to see. Barrie would publish his statement “Concrete” in Zurbrugg’s Stereo Headphones (reprinted Miki 2002 30) in 1970, with its explicit statement that “some sort of purist movement [in concrete poetry] . . . would be a great error.” He wants multiple entrances and exits. He also cites Scobie’s September 1968 letter in a way that could be misread as attributing to him the formulation of “clean” and “dirty” — when what Scobie had written was “what you called the difference between ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ concrete.” Quite possibly the terms had become so common in Barrie’s Ganglia conversations with Aylward, Harris, and Rob Hindley-Smith that he no longer thought of how they had developed as important.

Zurbrugg went on to write influential books on Beckett, Proust, Burroughs, and postmodernism, and to professorships in New Zealand and the UK. Barrie — emphatically more both poet and intellectual than an academic — teamed up with Steve McCaffery in 1971–72 to found “TRG” — the two-person Toronto Research Group — to investigate much the same literary field as Zurbrugg but with activist rather than interpretive intent. Their discussions, McCaffery writes, had included “[t]he possibility of radically altering the textual role of the reader; of extending the creative, idiomatic basis of translation; of a poetry that would jettison the word in favour of more current cognitive codes; and of a material prose that would challenge the spatio-temporal determinates of linearity” (1992 9). A formal print launch of TRG would become possible later that year, McCaffery notes, when “Frank Davey asked Barrie to become involved with the journal Open Letter. Davey offered him a section in each issue to ‘fill up’ in whatever way he wanted” (9).

Barrie’s route to Open Letter was actually somewhat quicker than McCaffery recalls. Around the time I was lunching with Barrie in September 1970 about Birney’s concrete poetry I had been working with editor Victor Coleman on beginning a new series of Open Letter in Toronto for which Coach House Press would be the publisher. Our application for Canada Council funding for our non-normal magazine was approved the next August, and we set a deadline of October 15, 1971, for material for the first issue. On October 5, 1971, I handwrote and mailed this note to Barrie:

I’ve been trying to reach you on the phone over the past two weeks. The Canada Council has just given me $2700 to restart Open Letter as an avant-garde review journal. The mag will be larger, contain mostly articles and reviews of small press publications, will be printed by Coach House, & will pay $3 a printed page. I’m offering a few people guaranteed open space in it for reviews or articles. Would this interest you? Our first deadline is 15 October (we’ll be publishing 3 times a year after that).

Do let me know if you’re interested.

A few weeks later George Bowering came to Toronto to promote his McClelland & Stewart collection Touch, and stayed for almost a week with me and my partner Linda. Various writers dropped in to see him, including Barrie — who tended, I was learning, to visit people rather than receive them where he was living. One night Barrie, George, and David McFadden persuaded Linda to become a writers’ agent — and arrange readings for them and try to sell their accumulating manuscripts. Barrie quickly became a regular visitor to our north Toronto house, appearing at the door especially on a Sunday or Monday evening on his way back from events at the Therafields farm. He would read new poems to us, or tip off Linda about hints he’d encountered about what schools or libraries might be open to appearances by her new clients.

His correspondence with Zurbrugg is one of a number of indications that Barrie was now considering adding critical and theoretical writing to his already numerous activities. The larger book projects he had undertaken at Ganglia — bissett’s we sleep inside each other all (1966) and Birney’s Pnomes, Jukollages & other Stunzas (1969) — had required in his view not only the advocacy implicit in publishing them but an introduction or afterword that explained or defended visual poetry. By the time I met him he had begun trying to write a book on Gertrude Stein, a writer from whom he has learned much but who, he believed, had never received appropriate advocacy or explanation. It was to be “a book on Gertrude Stein’s theories of personality as revealed in her early opus The Making of Americans” (Miki 2002 318). Barrie offered Open Letter one of the first chapters, which he had drafted the previous April (in his notebook the draft accompanies texts dated April 20, 1971), “some beginning writings on GERTRUDE STEIN’S THEORIES OF PERSONALITY.” Victor and I had idealistically conceived of this Open Letter series as an artist’s series in which we would do minimal editing and allow each contributor control of the layout, typography, citation style, and spelling employed; our artist contributors — bill bissett would contribute an essay to the sixth issue — would have thought through their positions on such matters, we believed. Barrie’s essay, like his prose in Two Novels, and like Birney’s later poems, had no conventional punctuation marks; he used space instead. He cited quotations as “(p. 166)” rather than as plain parenthetical numbers. The quotations themselves were unusually long — more of the essay’s lines were Stein’s than were Barrie’s — and undoubtedly offended fair-use copyright laws. Barrie sometimes had little to add to them except that her insights were “amazing,” “remarkable” (Miki 2002 77), “precise” (80), or “enormous” in their ramifications (74). Victor and I, in our dogmatic respect for artists’ wishes, had the typesetters set the essay as received — difficult to do because of the various approximations of typewriter spacing that had to be made. It became the first multi-page article Barrie published in a journal.

A little later Barrie showed me another piece he had written — under the pseudonym bpLichon — “a review of bpNichol’s ‘some beginning writings on Gertrude Stein’s Theories of Personality’ as published in Open Letter 2/2,” and which he was considering also publishing in Open Letter. Instead he left the manuscript to be discovered in the SFU fonds; it would be published in Roy Miki’s Meanwhile: The Critical Writings of bpNichol in 2002. “Lichon” was unhappy with Nichol’s punctuation. Barrie had had him write that “Nichol has taken what he was doing in For Jesus Lunatick & extended it through the incorporation of hints gleaned from [Hansjörg] Mayer1 but he has not taken it far enough.”

in this i can see his (at this point) failed attempt to express how his perceptual system has been altered by his encounter with Stein’s perceptual system [. . .] i know for a fact these first notes of Nichol’s were written in the spring of 71 & submitted to Open Letter without revision obviously enough came through to the editors that they saw fit to publish them without insisting that Nichol make his intent clearer seeing this we can say that Nichol has partially succeeded but the hesitancy in & tentativeness of these first notes shows through in his lack of mastery over his own structures (he is (for instance) still wrestling with how to handle the differentiation between commas & periods he has set out to create punctuation anew to serve his own ends & has not succeeded) (Miki 2002 96)

Barrie and Steve McCaffery — an artist whose academic background had led him to be more specific in his arguments than Barrie and arguably more scholarly in his innovations — were now discussing many of Barrie’s publications as they occurred. Some of their discussion in this case, Barrie indicated to me, had led to his second thoughts and Mr. Lichon’s reflections.

Barrie would soon abandon his Gertrude Stein book project — largely because he was sensing that by extracting his numerous quotations he might be offending her belief in a “continuous present” and her request that her readers “Give the text the reality of its existence as an object & let that object be continuously present to you.” He would explain in 1983:

. . . how could I continue extracting? I was violating Stein’s text when I did that, the very spirit of her text, & I was, of course, proving the validity of Heisenberg’s Principle of Uncertainty as it applied to literature. By extracting I was bringing the text to a dead halt & we were no longer observing it as it was & therefore our observations ceased to have any validity (Miki 2002 319)

His explanation, with its invocation of Heisenberg, had major implications for the subjectivity of his own writing — for example, could the bpNichol “i” that narrates The Martyrology and reads and often disassembles and reassembles its words be the same as the “i” that records its text, organizes its sections, or arranges its publication? As literary theorist and critic Terry Eagleton would write in 2003, “The free subject . . . cannot itself be represented in the field which it generates, any more than the eye can capture itself in the field of vision” (214).

But Barrie’s April 1971 chapter did illustrate the continued centrality of psychoanalytic theory in his ongoing thoughts about writing. He wrote there of Stein’s The Making of Americans, its personality theory of “bottom nature,” and its subtitle “a history of a family’s progress” that the work was

not so much a novel as an attempt to encompass the shifting forms of human personality in words to create a vocabulary with which to describe them the subtitle is accurate on more than one level the family is all of man and the history is everyone it is in that sense an epic on a scale never attempted before or since [. . .] beyond that it is perhaps the only major work on human personality that has never been approached or studied as such this then is the bottom nature of what i’m trying to do (Miki 2002 72–73)

His curious blending of concern both with “personality” and “epic” operate here to blend psychoanalytic and literary theory. Moreover, his description of a text that focuses on family and history and “shifting personality” and that is an “epic” in which “the family is all of man” is one that could also describe the two books of The Martyrology which he was about to publish — and that would become increasingly descriptive of the poem as the overall nine books developed. His “epic” would be written on an even larger “scale” than Stein’s. As well, in those April pages of his notebook he was also drafting the “Future Music” passages of The Martyrology, Book II, and writing to himself the comment “I want to write the history of this present moment” — a line that later became part of the poem and that was most likely inspired by his reflections on Stein’s “history” of “everyone.” Writing the “history of this present moment” returned Barrie to Heisenberg’s paradox — if he were to stop the moment’s motion he would be omitting part of its character but if he followed its motion he might never be able to indicate its substantiality.

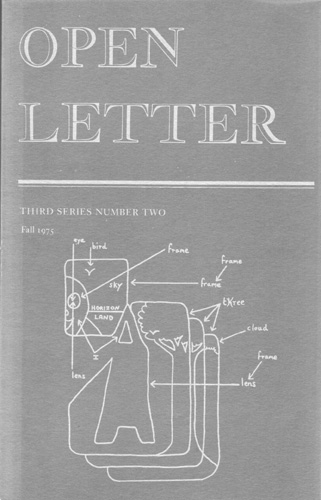

THE COVER OF OPEN LETTER, SERIES 3, NUMBER 2, 1975, SUBSTANTIALLY EDITED BY BARRIE AND DISPLAYING ONE OF HIS VISUAL POEMS.

In the following issue of Open Letter (Fall 1972) Barrie published a three-page review of Peter Finch’s anthology Typewriter Poems. Barrie employed a somewhat less ambiguous spatial punctuation, quoted none of the contents, and made cogent summaries of the various difficulties currently being encountered in “typewriter” and other visual poetries. He and McCaffery published the TRG manifesto and first report, on translation, in the Spring 1973 issue of Open Letter. The writing in these was anything but tentative. It was factual, confident, self-aware, critically self-referential — probably because of the two consciousnesses composing it — and at times humorous.

This work that Barrie began doing with McCaffery in 1971–72 as “TRG” was in a way one of the last major sites of Barrie’s self-training. He had trained himself in visual poetry and in writing “regular” poetry that avoided arrogance and predictability. He had trained himself as a performer of sound poetry and as an editor and small press publisher. He had worked through his therapy to become a psychotherapist, and trained on the job to become an effective administrator of Therafields. In his dialogues and collaborations with McCaffery he was learning about the breadth of research and skepticism necessary to the making of generalizations, and the clarity of presentation necessary to avoid ambiguity and misunderstanding.