19. Blown Away

If we’re going to write OUR history then it must be US who write it. After all isn’t the work of theradrama bringing our past lives into our present consciousness and understanding them?

— bpNichol and Julia Keeler,

“The Autobiography of Therafields,”

A Publication 2, December 8, 1974

At the end of March 1979 Barrie had written to Montreal poet Stephen Morrissey that life was steadily unfolding as many intriguing revelations as it ever did, and that he currently had so many irons in his fire that he worried that he might get burned. This wasn’t quite the upbeat report that he was about to send to the Canada Council, but perhaps slightly more accurate. As well as working on all the literary projects he had told the council about, he was also about to draft his defence of Lea’s books for the “easily defensive” readers of A Publication; he had written to his mother telling her that he had begun a new autobiography, titled “Desiring to Become,” and asking her to send him a copy of every photo she had of him from his first 18 years — receiving the reply that he was welcome to any photo she had the next time he visited; he had recently received permission from fantasy writer Jack Vance to adapt part of his collection The Narrow Land as a comic book narrative. Meanwhile at the Therafields Florida house, Visvaldis — perhaps depressed over Lea’s chronic illnesses, or by the financial uncertainties of the corporation — had relapsed into his alcoholism, “fleeing to Mexico City,” Goodbrand writes, “and had sexual relations with women he picked up in the bars” (214). Barrie, who was already scheduled to co-supervise four weeks of summer marathons, then initiated plans for a series of three Therafields Environmental Forums, the first to be held at the farm in July with Visvaldis chairing. Barrie’s main goal in these, Goodbrand implies, may have been to return Visvaldis to sobriety and responsibility, although the announced aim was to design a large integrated rural centre to serve the farm members as a communal residence and work space. Barrie himself would chair the following two forums in October, with Visvaldis and other architects on their panels. But by November Visvaldis would have resumed his heavy drinking.

In August Barrie wrote to Janet Griffith, Rob’s former partner, and one of the original members of Hypno I, who had now left Canada. He described to her a marathon for therapists that Lea had recently managed to hold, and then wrote that the marathon had caused him not only to think of her, but of all the people he’d begun the Therafields part of his life with and who had left to follow other paths. He’d begun feeling how much he missed them all. He’d realized that when they had all been planning, building, and talking back in the late 1960s he’d imagined that they’d all be together, doing similar things, forever. Barrie was still not an eager writer of letters, and there are no other letters to or from Griffith in his files. He seems to have written this letter on impulse, under the growing pressure of the interpersonal and financial Therafields crises. His nostalgic tone, with its intimation of a lost immortality, seems to have been evoked not only by his memory of Griffith but also by his awareness that many of his present Therafields friends, including those at Lea’s marathon, might very well soon also be in his past.

In September 1979 the Therafields farm held a large “fall fair” open house and hosted more than 3,200 visitors. But during the same week Barrie and the other Advisory Board members met with bankers and agreed to split Therafields into three parts — therapy, community, and real estate — and began consultations about the financial arrangements the split would require. Both Lea and Visvaldis failed to attend the meeting. For the next two years Therafields would often appear outwardly to be operating as usual, but behind the scenes house groups were being disbanded, real estate was sold to indemnify members who had been shareholders, and therapists were beginning to operate as private businesses. Barrie himself would be giving much less thought to its future, and much more to his personal and writing lives, although he did expect to continue to help manage Therafields as a corporation that at least provided offices and other services to independent therapists.

He had sent the latest draft of his novel “John Cannyside” to Ondaatje in July, with a note that the Coach House board should publish a poetry manuscript by Sharon Thesen and attempt to get the manuscript of Daphne Marlatt’s Rings — later published by New Star Books. The previous August he had received a letter from Stan Dragland to write an introduction to an imaginary or “uncollected” “Canada, a Prophecy” anthology, for publication in Dragland’s Brick magazine — modelled on Jerome Rothenberg’s recently published America, A Prophecy. Misunderstanding this as requiring him to compile a list of the imaginary anthology’s contents, and to do the extensive archival research that would require, and perhaps even to produce an actual anthology, Barrie had delayed responding for a year until again prompted by Dragland. “CANADA: a prophecy” is such a blatant steal, he had replied, but it certainly conveys what you’re talking about. He agreed to do some work on it, writing that it would probably be late fall before he could find the time. He told Dragland that he had too many projects underway right now to do any more, but that he’d “really” like to this one. The misunderstanding would continue for a couple of years, but Barrie’s willingness to take on such a large task — if he could find the time — demonstrates his continuing concern about canonicity and about keeping alive earlier writing for the benefit of later writers. He had not forgotten how difficult it was when he was a teenager to locate actual Dada texts, or how obscure Sheila Watson’s writing had been when he stumbled across it. He went on to tell Dragland that he and Ellie were planning an extended drive out to the West Coast in September, including to Victoria, and that he was planning to work during the drive out on his own utanikki, to which he’d given the working title of “You Too, Nicky,” and that he foresaw as being a reworking of the “failed” “Plunkett Papers.”

Somewhat like the trip he had made with Rob in 1969, their drive took them to Saskatoon to visit Ellie’s parents, through Plunkett, and then up to Edmonton to visit Doug and Sharon Barbour, then to Vancouver and Victoria for four days before returning. He seems to have done considerable writing on the trip on the “You Too, Nicky” project, although the notebook in which he did much of it (titled “The Blue Jean Yes Notebook,” April 28, 1979, to November 11, 1979) later went missing — and with it his only copy of the original “Hour 8” of “The Book of Hours.” In October, after their return, he wrote to Fred Wah to explain his understanding of the history of the word “utanikki,” referring Wah to Earl Miner’s new book Japanese Linked Poetry.

November and December saw Barrie do some writing for the still not abandoned Four Horsemen novel project, “Slow Dust,” write various passages of poetry that he wasn’t sure were part of “A COUNTING” or perhaps a “prologue” to it, write drafts of a text titled “Imperfection: A Prophecy,” and begin a series of drawings titled “Interference Patterns.” He and Ellie were also concerned that she might be pregnant, something they became sure of in early January 1980. On January 22 he wrote a cheery letter, possibly deliberately cheery, to his parents announcing his impending fatherhood and jesting that it may have been inspired by his and Ellie’s Victoria visit. There is no reply to it in his archives — one can but imagine how it may have been received. He told them that he would be in Victoria again in two weeks’ time to give a reading at the university.

On Valentine’s Day he wrote contrasting letters to poets Ken Norris and Artie Gold. He told Norris that he was somewhat “blown away” because he and Ellie were about to have their first child — the due date was June 23 — and that the event was already opening new possibilities for both poetry and their lives. He told Gold that amid the crush of various events his writing was on the back burner, but that was okay because the changes that were happening were so bizarre and interesting. In his notebooks, however, he had been recording ideas for two novels, one titled “The Notion” and the other “Phone Exchange,” a novel that would feature a fictional bpNichol created from newspapers and magazine items, advertisements, and similar things. He’d also written a note about a possible text that would include a biography of “a bpNichol,” plus a text for his series “Probable Systems” and a text titled “Realism.” Barrie was apparently still very much aware of how he had invented his publicly performing self, and eager both to foreground its invention and to have some fun parodying how readers, reviewers, and journalists had presumed to perceive it — or how a future biographer might. But, more darkly, he also seemed unable to avoid foreseeing bpNichol — along with Knarn — someday dead.

In March he headed west again with the Four Horsemen to give eight performances in 12 days. The tour was an opportunity for him also to visit Daphne Marlatt in Vancouver, whose book What Matters he was editing for Coach House. Among the other editorial tasks he would return to were two books in the new Talonbooks Selected Poems Series. He was overseeing the typesetting at Coach House of his own selected poems, which he had now wittily titled As Elected, and editing and writing an introduction for my book in the series, The Arches. He would send that manuscript to Talonbooks on April 14. Also in April he would write drafts of “The Vagina” and “The Anus” for the series of poems he was titling “Organ Music,” and as well performing late in the month at the second International Festival of Disappearing Art(s) in Baltimore.

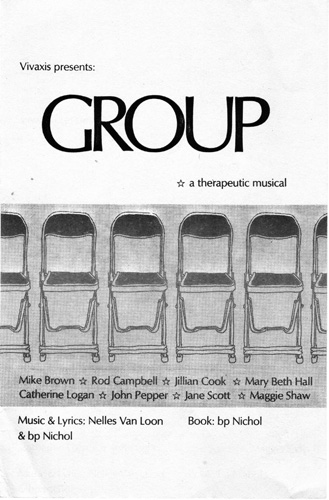

THE PROGRAM FOR BARRIE’S MUSICAL COMEDY GROUP, MAY 1980.

In May rehearsals began for the production of his musical comedy Group, now in two acts, and to be performed in Therafields’ Dupont Street group room in a six-night public run. It was an elaborate quasi-professional production with a director, choreographer, stage manager, lighting director, three musicians, and a publicist. Several of the performers were professionals with extensive experience in television or on Shaw Festival stages — as well as in Barrie’s artists’ groups. For Therafields members Group was a warm but poignant celebration of a context and set of beliefs that seemed likely soon to be gone.1 For outsiders it was an unusually sparkling joining of comedy and wisdom. Barrie was already thinking of restaging it in a larger theatre.

Meanwhile events at Therafields itself had become again more complicated. Although Rob and the corporation’s accountant Renwick Day could now see possibilities for financing development of the now independent farm or “rural” centre, resentment among the therapists was making the overall financial untangling of the three Therafields “parts” difficult. Many of the therapists wanted no future dealings with the corporation or its managers. Then on March 8, 1980 The Toronto Star published a somewhat paranoid article about “cults,” and named Therafields as a prominent example — as a group that “brainwashed” new members into yielding control of their finances and ambitions and insisted on communal thought and living. A politically nervous provincial government promptly appointed the sociologist and widely known human rights advocate Daniel G. Hill to inquire into the charges, which in June he reported to be without substance. But the brief tempest had strengthened the determination of many of therapists to be dissociated from Therafields, and led other members to leave. Goodbrand writes that of the 10 week-long summer marathons that had been in planning, seven had to be cancelled due to lack of interest and that seven of the 17 houses still owned were no longer needed for Therafields’ work (220).

In the second week of June Barrie and Ellie headed to the hospital for the impending birth of their baby. Barrie would later, in a letter dated July 16, tell Doug and Sharon Barbour, that when the doctor emerged from the delivery room and told him the news the one thing that went through his mind was the line of Stephane Mallarmé, “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” — “A throw of the dice will never abolish chance.” His and Ellie’s son had been stillborn. Barrie was initially terrified that Ellie might be dying also. Barrie’s mother received the bad news by telephone from Don, and sent Barrie “& Ella” a letter, assuring them that people get over such things with time. Possibly in previously refusing to mention Ellie in her letters she’d forgotten her name. Barrie would generously reply in July that both he and Ellie had thought of her own loss of her firstborn and of Ellie’s mother’s loss of a three-year-old son. He agreed that the passing of time could help, but suggested that a little “perspective” could also be useful. He told her as well that they were committed to trying to have a family together, and that they were likely to get married next October.

Two weeks after their loss he and Ellie decided to have a brief vacation in New York, where they saw a large Picasso exhibition and took in two Broadway shows. On their return Barrie, with some misgivings, resumed seeing his therapy clients. He wrote to his sister (July 26, 1980) that this wasn’t the most ideal work to be doing after such a loss, because a therapist draws so much on his own stockpile of inner joy in order to keep listening to his clients’ unhappinesses. When you encounter something so devastating, he remarked, you can quickly run out of resources.

There was even less joy that summer at Therafields as it became clear both that Lea was no longer capable of offering any leadership ideas and that both Rob and the therapists were in their own ways refusing the ideals on which most members, including Barrie, believed that she had founded its therapies. Barrie regretfully but tersely wrote to his colleagues in July “Whatever the term ‘Therafields’ described when Lea first coined it, it no longer describes the same physical reality. The Therafields of summer 1980 is not the Therafields of summer 1967. [. . .] We should honour the term by retiring it until we can use it in a way that won’t pollute the original feeling of challenge, joy, and promise we felt around it” (Goodbrand 220-21). Barrie’s brother Don had recently severed his ties to the corporation, and Barrie probably would have as well if he had not had responsibilities to oversee its debts and financial obligations to the therapists. In mid-August he and the other managers encountered yet another credit crisis and were forced to sell more houses.

In September he began teaching part-time at York University — a second-year creative writing course that he would teach, often with an additional senior course — until 1988. Barrie was already foreseeing the possible end of his paid work at Therafields, and I was coordinator of York’s new creative writing program and controlled its part-time hirings.

On October 11 Barrie and Ellie married, holding a reception at the Vivaxis restaurant. Their invitation — hand-drawn by Barrie — requested “A.L.S.A.P.U.T.C.” (“As Little Sentimentality As Possible Under The Circumstances”). Barrie, however, could not comply. He reported to Steven Smith, who was in the U.K. for the year, that he had been unable to keep from weeping, while Ellie had managed to appear calm throughout. He joked that they had reversed sexist stereotypes, while perhaps creating a few of their own.

The next weekend Barrie read at the three-day Canadian Poetry Festival in Buffalo, a festival co-organized by Robert Creeley and Duncan-scholar Robert Bertholf and attended as well by McCaffery, Wah, Marlatt, Tallman, and bissett. On his return he and Ellie began another mammoth move — from 131 Admiral Road into another large Victorian house, 99 Admiral Road, which they and Renwick Day and Grant Goodbrand were now jointly purchasing from Therafields. As well, Barrie was bringing home 25 cartons of books and other possessions from his room at the farm’s lavish “Willow” house, once Lea’s principal residence, which was now largely unused and likely to be sold. The move out of 131 had been occasioned, as had the one a year earlier, by Rob and Sheron. This time it was Lea’s interference with the care of their new baby that was the catalyst. Lea was now back living in her nearby house on Admiral with companions who attended to her failing health. Sheron narrated the story to Brenda Doyle:

I took it for about four weeks because I didn’t know any better. When the baby was born, Lea called and said, “I’m sending (one of her companions) over to stay with you for six weeks because you have no instincts.” She said she was very concerned about the baby because I was his mother. [But t]here is never a time that you are more intuitive than when you give birth to a baby. She was into this whole thing about only feeding the kid every four hours. [. . .] After a few weeks I said to Rob that it was all crazy. The child was crying and Lea’s companion was walking him up and down and he needed to be fed. [. . .] It was horrible for me. I hated her at that time and didn’t want her in the house. I felt like she was insanely jealous of me, that I had stolen Rob from her. (“Thoughts,” December 5, 2010)

The moves took only two weekends, but the sorting required to fit everything into the new space — Barrie and Ellie had only the ground floor — consumed most of the next two months. He told Smith in January that he had tossed out or sold “tons” of accumulated magazines and various books and become more organized than he had ever known himself to be. During part of this time he also was commuting with Steve McCaffery to London, Ontario, for rehearsals of his friend R. Murray Schafer’s musical/theatrical pageant Apocalypsis, for which he and McCaffery had advised and done small bits of writing, and in which they were now part of a cast of 500.

Again the new house and move were not things Barrie had desired. The move separated him from Rob, who moved with Sheron to King City, north of Toronto, where his sister Josie and her new husband Adam Crabtree were also now living. It may also have complicated his relationship with Lea. With each move the number of people sharing their house was becoming smaller, paralleling the shrinking of Therafields and collapse of its dreams of communal living. From the Admiral-Road-area house groups of the early 1970s most long-term Therafields members were now heading toward nuclear households.

Because of the various Therafields crises and changes, Barrie had been finding very little time this year for writing, except for drafting a few parodic dice-based board games — a Four Horseman board game, a TRG board game, and a “Time Times Time: the Eternity Boardgame” which he had begun in Victoria during his Feburary visit. He had also begun collecting board games. While working with me on an Open Letter project to collect Louis Dudek’s previously uncollected lectures and papers, he had encountered Dudek’s notes for a similarly parodic Monopoly-like “The Poetry Game.” Whether it was this encounter, or his general feeling that events in his life, particularly at Therafields, had become irrational, beyond any individual’s capability to influence or predict, dice-based board games had begun to dominate his thinking — to the extent that when his son was stillborn it was Mallarmé’s throw of the dice that he had recalled. It was an odd thought to find comforting, he had told the Barbours in that July letter, but it seemed reasonable to him. Then he had added that two or three weeks ago he had had a dream in which he was playing a board game, which seemed to be his own life, and there he was, dice in his hand, all ready to play again.

The one important work that Barrie would write in 1980 was “Hour 13” of his “Book of Hours.” He flew west in November with Ondaatje, taking a three-day break from unpacking and sorting his books, to give readings in Lethbridge and Camrose. Being away from Toronto and from Therafields business seems to have again released him to write. “Hour 13,” written while they were in Lethbridge, is the extraordinary “the heart does break” hour in which he ponders the meanings of his child’s stillbirth.2

He had also finally decided, somewhat before his trip to Lethbridge and Camrose, that he hadn’t really completed The Martyrology — that the new writing that he had thought was part of his new book, “A Counting,” had been actually an extension of Book 5. In a letter dated January 23, 1981, he explained this change of mind to Scobie, who had recently sent him the first chapter of the bpNichol book he was drafting, writing that he had now come to view “A Counting” as The Martyrology, Book 6. He had realized this, he told Scobie, only when he had finished “Imperfection: a Prophecy,” the first section or “book” of “A Counting,” and had noticed that all of the references that he had worked with there had come directly out of the Bran and Brendan material in The Martyrology, Book 5. Instead of having begun a new work — which, because of Barrie’s belief that he never worked on more than one work of discursive poetry at a time, would have meant that the Martyrology had ended (to his great “relief,” he joked), he had begun writing book sections “spawned” by the chains of Book 5. He predicted to Scobie that each of the 12 chains would give rise to a new Book 6 section, or “book,” and this Book 6 would be a “set of books.” He continued the letter by bemusedly reflecting on his repeated eagerness to have seen The Martyrology terminated, and by suggesting that it was more likely that its continuability was unlimited, that it could go on “forever,” so long as it “renews itself.” The letter, together with his now year-long puzzlement about whether his writing was extending The Martyrology or beginning a new project, showed the extent to which he had now separated the desires of Barrie Nichol from the assumed desires of his poem and its bpNichol writer. He was treating the poem much like Barrie Nichol would a therapy client — not directing its life but attempting to find out, and enable, what it “wanted” to do. The unrealistic optimism of “forever” aside, The Martyrology had become suddenly one of very few things in Barrie’s life apart from his marriage that he could realistically expect to continue. He was finally accepting it as a possibly “lifelong” companion.

The new work that had moved him toward this view, “Imperfection: A Prophecy,” was an example of the new kinds of writing he had hoped The Martyrology might contain. It began as playscript or masque, with the apostles addressed by Paul in Romans 16:7, Andronicus and Junias, fleeing Jerusalem while lamenting the personal imperfections that had caused them to do nothing to stop Christ’s slaying. In Britain the poem brings them together with the legendary and playfully promiscuous giant Buamundus as successful Christian missionaries, but who soon must flee westward into different and equally (im)possible story lines. The voice of this later part of the poem is the mischievously solemn bpNichol of Barrie’s “probable systems” texts of Zygal and Artfacts. In one “possible” storyline Buamundus becomes the “Sleeping Giant” of Port Arthur, and Andronicus and Junias the models for some Mayan carvings. In another Buamundus freezes in the Arctic while Andronicus and Junias disappear into the Pacific Ocean. The playful hypotheses continue the blending of deities and cultures — Horus, Brun, God, et cetera — that Barrie had begun in Book 5, Chain 3, and tip his theology sharply toward the multicultural and ’pataphysical.

what it all adds up to

. (the end)

Andronicus — apostle ?

Junias — apostle ?

Buamundus — giant ?

the known guessed at

thus conclusions

and/or theories

viz: science and history

myth and legend

some sense of

the components of

reality

(“Book I,” The Martyrology Book 6 Books)

Barrie’s concluding deconstruction of the word “religious” into “a region of the real / uncharted / (largely) // open to misconstruction / and fanaticism” offers a semantically rich rebuke to readers who have classified him as a “religious poet,” suggesting that he was a poet of an even larger metaphysical curiosity. Even the scholarly possibility that Junias — whose name was also recorded in early manuscripts as Junia — may have been a female apostle is left open here. Nowhere does the text assign either “her” or Andronicus a gendered pronoun.