Chapter 4

September 11

3: The days after the day after

Don Juan in Hull

Elena yawned lavishly and said to him, ‘It’s midnight.’

‘That’s true, El. It is now September 13.’

‘And I’m tired…Why does she call Larkin the poet from Hell?’

‘…It’s not in the sense of, I don’t know – the neighbour from hell. He was the poet from Hell, capital aitch. Hell was where he lived. Hull. A port city in Yorkshire, Pulc, where the constant mist reeks of fish.’ With his sound hand Martin got hold of the Scotch bottle and poured himself a big one. ‘He wasn’t from Hull yet, mind, not in 1948. He was still pulling his wire down in Leicester.’

‘How old was he then? Was he just a librarian?’

‘Mm, and he wasn’t a poet yet either, not mainly. He was Kingsley’s age, so twenty-six. But he was a red squirrel all right. He’d already published two novels.’

She said, ‘Like you.’

‘…Uh, yeah, now you mention it.’ He drank. ‘You know, at that stage it looked as though Larkin would be the novelist and Kingsley’d be the poet. If anything.’

‘Your wound’s seeping. Use the roll.’ She took up the pages. ‘PL as she now calls him got to Ainsham in time for Christmas Day. And he was still there when Kingsley crept back with his dirty laundry on New Year’s Eve. So there was an awkward but in the end “very jolly” Hogmanay. In quotes. I see. They all got pissed.’

‘Yeah, assuming they had the cash. They were very poor. I was a penniless baby.’

‘Kingsley said he knew at once that something had happened. He was frankly relieved because it sort of equalised the guilt. PL took his leave on Jan 2 and K and Hilly, after a cagey interlude, got back to normal. At which point they discovered Hilly was pregnant. With you, Martin. And Kingsley hadn’t laid a finger on her since November.

‘They agreed that they’d never say anything to PL. Who would’ve been horrified, don’t you think? Being a child-hater?…And life went on.

‘Anyway, such was Kingsley’s account. And of course he swore me to absolute secrecy. Well, that vow I considered void the moment I saw his obituary. For six years I’ve been wondering when it would be best to tell you and so free myself of this awful burden. Oh, sure…I feel better already. Yeah, I bet you do.

‘New paragraph. I heard him out and I told him quite firmly, “I’ve always thought of you as Martin’s father, so the taboo is still there and I can’t pretend it isn’t. Sorry to disappoint, but there we are.” He was a perfect gent about it, as I said. Then we watched the news and he played some jazz, you rang, and I went to bed (I was already ailing from the Parfait Amour).

‘We’re coming to the last bit. God, this – this calligraphy’s positively gruesome. So bad luck, mate. Rather confusing, no? Still – not the milkman! exclamation mark. Not the milkman. Just the wanker from Hell. Yours, Phoebe Phelps. PS. It broke my heart to hear about poor dear Myfanwy. You must feel so horribly guilty…

‘Dot dot dot. The end.’

They sat for a time in silence.

‘Elena, which one is lying? Was he lying? Or is she lying?’

‘…Most likely they’re both lying. He lied to get her into bed. Which he no doubt did anyway, without lying, without exerting himself in any way. She lied about that. And now she’s lying about this.’

He waved his bandaged hand in the air. ‘Wait. Give me a moment to…’ Just then the dishwasher churned into life. ‘You know, some of this is plausible – the stuff about 1948. Okay, circumstantially plausible. But psychologically plausible too.’

Elena was sceptically considering him. He went on,

‘See, Mum always admired and respected Philip. I’ve been looking at the Letters. Kingsley’s. She’d dress up – she needed some persuasion but she’d dress up in sort of babydoll outfits, and Kingsley took photos and sent them to Hell. Hull. No. Leicester. Oh yeah. And Mum woke up once saying she dreamt Philip was kissing her. I don’t know. The jolly Hogmanay rings true. Kingsley wouldn’t have minded that much. If at all.’

‘Because he was drunk.’

‘No – because he was queer. Kingsley was a bit gay for Larkin. And you know how that works. Like Hitch approving of me sleeping with any girl he’d slept with.’

‘…Why does Phoebe have it in for you?’

‘Hull hath no fury…There’re others like that,’ he vacantly continued. ‘Hull is other people. Don Juan in Hull. The road to Hull is paved with good intentions.’

‘Did you ever scorn her?’

‘Phoebe? Turn her down, you mean? No.’ Certainly not. Are you kidding? But then of course he remembered – the stairwell, the bathroom, the swollen breasts. ‘Yes I did. Once. Very late on. After it was over.’

‘Well there’s that. And there was Lily. You’re not seeing the obvious with Lily. You confine Phoebe for a night alone with your father, while you go off to Durham to rescue an ex. Jesus. And don’t tell me she didn’t reward you. No need to ask. In general, though, your conscience is clear.’

‘More or less. Over the five years. But I did end it – to get married to someone else.’

‘Was there any overlap?’

‘No. There would’ve been if I hadn’t turned her down. That one time.’

‘All right.’ Elena gave a shiver of dismissal. ‘What this shows, at most, is the lengths your father would go to for the chance of a fuck. Now you get this straight.’ And her glass came down on the tabletop, like a gavel. ‘I’m serious, Mart. This girl knows you and thinks she can toy with your head. Like you’re a lab rat. Don’t let her.’

He raised his palms and said, ‘I’ll try.’

‘You’ll try? Listen. Ask your mother! Ring her tomorrow and ask her.’

‘I can’t ask her over the phone.’ Or in person, he thought. ‘Nah. Mum didn’t have a go at adultery for another ten years. And it never sat well with her. She was a country girl. She was twenty. No. The idea of her being uh, consoled by Larkin with Nicolas sniffling in his cot. No, I don’t believe that part for a moment.’

‘Promise? Do you realise that not once’ve you…You always call him Dad. But you haven’t done that once tonight. You’ve called him Kingsley.’

‘Is that so?’ He shifted in his chair. ‘And what about his father, Larkin’s, that filthy old fascist Sydney? I’m giving myself cold sweats just imagining the horror of being a Larkin male. You’d have to look quite like him too. Imagine that.’

‘There you are then. You’re the spit of your father. Identico.’ Those were her words. But now she was frowning and gazing at him – with her aesthetic eye, her genealogical eye, feature by feature (and Elena, in speaking of cousins and old family friends, had been heard to say such things as She’s got her grandmother’s lower lip or He has his great-uncle’s earlobes). ‘No. It’s her you look like. Your mother.’

The hidden work of uneventful days

I felt its concussive magnitude: September 11 looked set to be the most consequential event of my lifetime. But what did it mean? What was it for?

‘The main items of evidence’, said Christopher on the phone from DC, ‘are the fatwas issued by Bin Laden in ’96 and ’98. And both are blue streaks of religious parrotshit, with a few more or less intelligible grievances listed here and there.’

I said, ‘From now on Osama should let the intellectuals state his case. What the fuck is going on with the American left?’

‘Yes I know. What does it like about a doctrine that’s – let’s think – racist, misogynist, homophobic, totalitarian, inquisitional, imperialist, and genocidal?’

‘Maybe the Marxists like its hard line on usury. Christ, let’s have some light relief. Tell me about Vidal and Chomsky. I know Gore, but you know them both.’

‘Mm, well, Gore’s got this side to him. Remember that guff about FDR being in on Pearl Harbor? If a conspiracy theory traduces America, then Gore’ll subscribe to it. With Gore it’s just a fatuous posture. With Noam, I’m sorry to say, it’s heartfelt. He just doesn’t like America. As he sees it, it’s been a sordid disaster starting with Columbus. He thinks America’s just a bad idea.’

‘A bad idea? We can argue about the practice, but it’s a good idea.’

‘Agreed. If Gore’s addicted to conspiracies, Noam’s addicted to moral equivalence. Or not even. He thinks if anything Osama’s slightly more moral than we are. As proof, he reminds us that we bombed that aspirin factory in Khartoum. Killing one nightwatchman. I had to point out to him that we didn’t bomb crowded office blocks with jets full of passengers.’

‘…Well keep it up, Hitch. You’re the only lefty who’s shown any mettle. It’s your armed-forces blood – the blood of the Royal Navy. And you love America.’

‘Thank you, Little Keith. I do, and I’m proud that I do.’

‘You know, what I can’t get over is the dissonance. Between means and ends. The intricate practicality of the attack – in the service of something so…’

‘Benthamite realism in the service of the utterly unreal. A global caliphate? The extermination of all infidels?’

‘The whole thing’s like a head injury. Last question – I’m being called to dinner. Will there be more?’

‘Maybe that’s it for now. But it’s probably just the beginning. We’ll see.’

What we saw the next day was the delivery of the first of the anthrax letters. And at that point the occult glamour of Osama reached its apogee. It was as if his whisperers and nightrunners were everywhere, and you could almost hear the timed signals of his hyenas and screech-owls, and rumours were skittering about like a cavernful of bats.*1

There would be a war – no one doubted that.

…‘The silent work of uneventful days’: this prose pentameter is from Saul Bellow’s autobiographical short story ‘Something to Remember Me By’. He means the times when your quotidian life seems ordinary, but your netherworld, your innermost space, is confusedly dealing with a wound (for Saul – he was fifteen – the wound was the imminent death of his mother), and has much silent work to get through…The populations of the West were for now otherwise occupied, with the coming intervention in Afghanistan; they were busy; and the silent work it very much needed to do would have to wait for uneventful days.

An act of terrorism fills the mind as thoroughly as a triggered airbag smothers a driver. But the mind can’t live like that for long, and you soon sense the return of the familiar mental chatter – other concerns and anxieties,*2 other affiliations and affections.

Like everyone else I processed a great many reactions to September 11, but none proved harder to grasp than the reaction of Saul Bellow. Somehow I just couldn’t take it in.

There was no difficulty in understanding Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell (those Chaucerian racketeers of the Bible Belt), who said that September 11 was due punishment for America’s sins (especially its failure to criminalise homosexuality and abortion). It was rather harder to tell what Norman Mailer was going on about when he said that the attack would prove salutary, because only ceaseless warfare could maintain the virility of the US male…And more routinely I attended to all the appeasers, self-flagellators, defeatists, and relativists on the left, as well as all the pugnacious windbags on the right; and I could see their meaning. Even Inez’s struggles I could faintly make out.*3 But not Saul’s.

‘He can’t absorb it.’

‘What?’ I was on the line to Mrs Bellow in Boston. ‘Can’t absorb it?’

Rosamund was confining her deep voice to a throaty whisper, so I knew Saul must be somewhere in the house – the house on Crowninshield Road. She said,

‘He keeps asking me, Did something happen in New York? And I tell him, in full. And then he asks me again. Did something happen in New York? He just can’t take it in.’

And I couldn’t take it in either – the news about Saul.

Two years earlier Saul had personally fathered a child (setting some kind of record) and his somatic health seemed imposingly sound (Rosamund still described him as ‘gorgeous’); but the fact remained that Bellow was born in 1915.

For some while there had been an uneasiness having to do with his short-term memory; and in March 2001 Saul was tentatively diagnosed with ‘inchoate’ dementia (whose progress would be gradual and stop-start). I went to Boston that spring and was present on the morning of an important test or scan; the three of us then had lunch in a Thai restaurant near the medical centre, and for the first time I heard mention of Alzheimer’s.

She disguised it but Rosamund, I thought, was (rightly and prophetically) alarmed. Saul was reticent but seemingly untroubled; it was as if he’d made a resolution not to be cowed. He would be eighty-six on June 10…A little later, in July, the Bellows came to stay with us on Long Island. I convinced myself that ‘all marbles’ (to quote the title of a novel he would never finish) were ‘still accounted for’ – until I watched our home movie of that visit, which was full of portents.

My habitual response to disastrous diagnoses of close friends, as we’ll see, was one of studied insouciance: fatal diseases, in this world view, were hollow threats, scarecrows, paper tigers…

All the same, back in London after Labor Day, I made an effort to discover what all the fuss was about: I got hold of a couple of books and tried to settle down to them. But I found myself immediately unnerved: Alzheimer’s clearly meant what it said; Alzheimer’s followed through. And I, I, who cruised through whole libraries devoted to famine, terror-famine, plagues, and pandemics, to biological and chemical weaponry, to the leprous aftermaths of great floods and earthquakes, was quite unable to contemplate dementia – in its many variants, vascular, cortical, frontotemporal, and all the rest.

Why? Well, call it the universal cult of personality, call it the charismatic authority of the self – the divine right of the first person. And this particular numero uno wasn’t going to wake up one morning in the Ukraine of 1933 or in the London of 1666; but anybody can wake up with Alzheimer’s, including the present writer, including the present reader (and most definitely including about a third of those who live beyond sixty-five). As ever, I was Saul’s junior by three and a half decades. Even so and even then, reading about Alzheimer’s brought me close to the onset of clinical panic…The death of the mind: dissolution most foul, internal treachery most foul – as in the best it is, but this most foul, strange, and terrifying.*4

Iris

Now it happens that life (normally so slothful, indifferent, and plain disobliging) had gone out of its way, in this very peculiar situation, to provide me with a ‘control’, a steady point of comparison: if I wanted to know what Alzheimer’s could do to a brilliant, prolific, erudite, lavishly inspired, and excitingly other-worldly novelist, then I needed to look no further than the example of Iris Murdoch.

Iris was a very old friend of Kingsley’s. As undergraduates they were both card-carrying Young Communists – they marched and agitated and recruited, heeding the diktats of Moscow. And in later life they continued to fraternise as they crossed the floor (more or less in step) from Left to Right…

So Iris had been an intermittent presence since my childhood. The last time I saw her was at a party or function in 1995 or 1996. It was being put about in the press, around then, that she was suffering from nothing more serious than writer’s block; I had no reason to doubt this polite fiction, and I said,

‘How awful for you, Iris.’

‘It is awful. Being unable to write is very boring. And lonely. I feel I’m somewhere very boring and lonely.’

‘Writer’s block – I get that.’ Yes, but only ever for a day or two. ‘You can’t do anything but wait it out.’

She said hauntedly, ‘And I already have a waiting feeling.’

We talked on. Present as always throughout was Iris’s one and only husband, the distinguished literary critic John Bayley (who was crooked forward in gentle commiseration). As I was leaving I laid a hand on her wrist and said,

‘Now Iris. Don’t let yourself think it’s permanent. It isn’t. It will lift.’

‘Mm. But here I am somewhere dark and silent,’ she said, and kissed me on the lips.

That at least hadn’t changed. With Iris (who was Irish), if she liked you she loved you. It was the way she was – until February 8, 1999, when she ceased to be.

Not satisfied with giving me a control experiment in the example of Iris, life, in September 2001, was suddenly giving me a detailed crash course on the further decline of Iris: earlier in the summer Tina Brown (then editor of Talk magazine) had asked me to write a piece about Iris, and to this end I read John Bayley’s two memoirs (Iris and Iris and the Friends) and arranged to go to a preview of Richard Eyre’s biopic, Iris. So I was in no position to echo Harvey Keitel’s line in Taxi Driver: ‘I don’t know nobody name Iris.’ In principle, I knew a fair amount about Iris, and about Alzheimer’s, or so you might suppose.

…Towards the end of the morning of Friday, September 14, I went to the screening room off Golden Square. In the thoroughfares the pedestrians, the comers and goers, still gave off an impression of tiptoe or sleepwalk, a flicker of contingency, as they moved past the boutiques and bistros of aromatic Soho…John Bayley was standing at the door; with a dozen others we took our seats as the lights were going down.

Kate Winslet plays the younger Iris – all hope and promise and radiance. Judi Dench plays the older, incrementally stricken Iris: her growing apprehension, and then the shadowing and clouding over as her mind starts to die. And before very long you are the witness of an extraordinary spectacle: Britain’s ‘finest novelist’ (John Updike), or ‘the most intelligent woman in England’ (John Bayley), sits crouched on an armchair with an expression of superstitious awe on her face as she watches…as she watches an episode of the preschooler TV series, Teletubbies.

This is now Iris on a good day: Iris, the author of twenty-six novels and five works of philosophy, including Metaphysics as a Guide to Morals. And you thought, Oh, the tragicomedy of brain death, the abysmal bathos of dementia…‘It will lift,’ I had told her in 1995 or 1996. ‘It will win,’ says the young doctor in Iris. And he was right.

After the lights came back up I established that the only dry eyes in the house belonged to Professor Bayley. Perhaps he was seeing the film for the second time – or let’s say the third time, in a certain sense. We only had to watch it, but John, in addition, had had to live it.

It won’t be like that with Saul, I kept saying to myself, almost dismissively, throughout the autumn. He couldn’t ‘take in’ September 11. Well who could?

It won’t be like that with Saul.

The first crow

‘Hitch, when did all this get going? Islamism. When did Muslims stop saying Islam is the problem and start saying Islam is the solution?’

‘In the 1920s. Atatürk dissolved the Caliphate in ’24, banned sharia, and separated church and state. The Muslim Brotherhood was founded four years later. Islam is the solution was the first clause in its charter.’

Then I asked him: when did jihadi attention turn from the near enemy to the far enemy? When did it turn from the Middle East to the West?

‘I suppose 1979 is the date. Khomeini versus the Great Satan. Or 1989. First, the Ayatollah provokes an epic war with Iraq. And with that out of the way he –’

‘And how many dead? I’ve read that Iran lost a million. Can that be true?’

‘Nobody’s really sure. But prodigious. And while the citizens of Persia are digesting that, the loss of an entire generation for no gain, Khomeini looks for a means to “re-energise the Revolution”. I.e., to regather some legitimacy. He needs a cause. And he alights on…The Satanic Verses. And our friend.’

‘Mm. Khomeini said Salman was paid a million dollars by world Jewry to write it…What did Salman call the fatwa?’

‘Looking back, he called it the first crow flying across the sky.’

A day or two later Christopher said, ‘Tell me about the feeling over there.’

‘Well I did an event the other night. And for once you could mention America without the room freezing over. Instead you got a wave of sympathy and fellow feeling. I think it’s like that all over Europe. Even in France.’

‘It’s worldwide. There were candlelit vigils in Karachi and Tehran. Both Shia of course. The Shias having always been slightly cooler than the Sunnis.’

I said, ‘Quite a bit cooler…America’s in Britain’s good books for now. But of course the softening of mood doesn’t extend to Israel.’

‘Mm. Are they saying that all the Jews who worked in the Twin Towers called in sick on September 11?’

‘No. That’s conspiracy stuff, that is. In England, as you know, anti-Semitism is just another chore of snobbery. Though it does lend spice to their anti-Zionism.’

‘It’s the same here. I seem to be surrounded by people who think…They think that Osama would take off his trunks the minute there’s a country called Palestine. Or the minute we lift the sanctions on Iraq. Et cetera. They don’t understand. I think Osama probably does lose sleep about those GI “devils” polluting Mecca and Medina. But inasmuch as it’s secular, his casus belli is about the end of the Islamic ascendancy. What bothers him is that the Muslim host was defeated at the gates of Vienna. The year was 1683 and the date was September 11.’

Later in the week he said,

‘Mart, what do you hate about America? I don’t mean its wars. I mean internally.’

‘Oh, there’s no end of things to hate. America is more like a world than a country – attributed to Henry James. And it’s the best starting point. You can’t say you love a world…Generally, what do I hate?’ And I started out on the usual roster. Racism, guns, extreme inequality, for-profit healthcare…Oh yeah, and the Puritan heritage. I can’t bear the way they love to say “zero tolerance”. It means zero thought.’

‘So all that. But what Osama hates about America isn’t what we hate about it. It’s what we love about it. Freedom, democracy, secular government, emancipated chicks driving around in cars, if you please.’

‘And plenty of sex.*5 I was reading…in Islam, apparently, Satan, Shaytan, is first and foremost a tempter. Whispering to the hearts of men. They’re tempted by America. Because a side of them fucking loves it.’

‘Yeah, that’s certainly in the mix. How dare America have the arrogance to tantalise good Muslims? Osama didn’t include that in his list of wrongs.’

‘With Osama I sometimes think fuck it, it’s all to do with birth order. I mean, seventeenth out of fifty-three – that’s a notoriously difficult spot.’

‘And living proof that his dad, the illiterate billionaire, wasn’t at all opposed to fornication. In Islam there’s no free love till you’re dead. With the virgins.’

‘With the virgins. And on that cool white wine that makes you drunk without any impairment or hangover.’

‘Mm, I sure could use a little of that. Yes, rightly did Khomeini call life, actual life as we know it, the scum of existence. Ah, Christ. This is a fight about religion, Mart. Don’t let anyone tell you any different. And those fights never really end.’

Equinoctial

It was September 26, and he was vainly pleading with his wife. Elena had not weakened in her determination to go to Manhattan (and to Ground Zero).

‘Don’t do it yet awhile, El. Any day now they’re going to start fucking up Afghanistan. And then we’ll have another Walpurgis Night in New York. I hate it when you fly anyway. Don’t do it yet awhile.’

She said, ‘What’ll they do there after they kill Osama?’

‘Uh, kill Mullah Omar, the one-eyed cleric, and so get going on the Taliban.’

Elena and her husband, for their part, were walking at dusk along Regent’s Park Road, heading for Camden Town and Pizza Express. Eliza and Inez would be waiting for them (minded by their faithful nanny, Catarina)…He looked around and sniffed the air. There was an instability in the weather, moist, brisk, rich, with a seam of something unsettling and arousing, like a welcome but careless embrace; the taste of it was familiar, too, though for now he couldn’t tell why or how. It would come to him. Elena said,

‘Well I’m off the day after tomorrow. Sorry, mate, but there it is. I have to.’

After a couple of moments he made it clear that he would accept this without much further complaint. At the same time he dimly consoled himself with the thought of a night or two of snooker and poker (and perhaps a night of darts with Robinson).

She said, ‘Uh, how did it work itself out with Phoebe? You know. After you got back from your quid pro quo with Lily. Up north.’

‘Oh.’ They turned into Parkway and there across the road were the outdoor tables and the milk-bar lights of Pizza Express. ‘Oh, we got past it somehow.’

But now they were within (and he could see the back legs of Inez’s highchair just round the corner). There were greetings and hugs and kisses, and it was almost the same – almost the same as before.

‘Four Seasons, me,’ he said. ‘And you?’

‘American Hot,’ said Elena.

As he drifted in and out of the small talk, doing more gazing than listening, his thoughts gingerly and discontinuously returned, not to the night of shame with Phoebe but to what followed it: i.e., the month of shame with Phoebe. During that time he very closely resembled Humbert Humbert in Part Two of Lolita.*6 As you get older you can of course remember what you went and did when you were younger; you can remember what you did. What you can’t remember is the temperature of the volition – of the I want. You can remember why you wanted what you wanted. But you can’t remember why you wanted it so much.

Their pizzas came, and while they ate Martin joined the conversation (a notably unstructured exchange about the dangers faced by somnambulists, especially those somnambulists who lived on aeroplanes, as Eliza planned one day to do). But it was not yet seven o’clock and he wasn’t hungry enough, so he made what progress he could with the house red before slipping outside for a smoke…

It had never bothered him, morally – what he thought of as the transactional phase or blip in his time with Phoebe. All the haggling and counterbidding was conducted in a febrile, giggly, not to say mildly hysterical spirit; it was comic relief from the gravity of a wrecked childhood, and somehow allowing them to move sideways – into their earthly paradise…Martin ground out his cigarette under his shoe and went back to watch the girls primly wallowing in their ice creams.

‘I need to see the ruin,’ Elena said outside. The others had gone on a few yards ahead (Eliza shouldering her way through the wind). ‘I want to see what’s left.’

‘They say it stinks…There’s a couplet of Auden’s daubed all over the city. The unmentionable odour of death / Offends the September night. And it does smell of death, apparently. And of liquefied computers. Hitch says he took all his clothes straight to the cleaner’s.’

‘I want to feel the weight of what came down…’

He took her arm. ‘Are you going to write about it?’

‘Maybe.’ When Elena emphasised maybe on the first syllable, as here, she usually meant yes. ‘Come on,’ she said. ‘Walk me to the Zoo and back. Come on.’

At the gate to the front garden they peeled off from their daughters and made their way in shared silence to the northern rim of Regent’s Park. The taste of the air: it wasn’t local, he realised, or even hemispherical, or even terrestrial. Yes, the equinox, when day and night went halves on the twenty-four hours; it happened twice a year (the third week in March, the third week in September), as the sun crossed ‘the celestial equator’. So for an interlude you were subject not only to the home biosphere but also to the solar system and its larger arrangements. Did this explain the accompanying arrow shower of physical memories? You felt yourself as a multi-annual being; and instead of making you feel old, as you’d expect it to do, it made you feel young, precariously connecting you to earlier incarnations, to your forties, your thirties, your twenties, your teens and beyond, all the way from experience to innocence…The Child is Father of the man. True, O poet of the lakes; and twice a year, in March, in September, the man is father of the child.

…Standing at the railings near the Zoo’s entranceway, they listened hopefully, and lingered long enough to pick up the odd neigh, whinny, roar, and trumpet.

They started back and after a few paces Elena said, ‘For how long did she give you a hard time about Lily? Phoebe.’

He readjusted. Then he said, ‘She didn’t. She barely mentioned it. Maybe she was still nuts on Parfait Amour. Weird, because Phoebe wasn’t one to forgive and forget. But she seemed to let it go. I wonder why.’

Elena tightened her grip on his arm and brought him to a halt. She turned full face, full face, and pale in the light of the conscious moon.

‘Well now you know. That settles it, fool. She’d already got her own back – with your father.’ Elena shook her head. ‘You’re as blind as a kitten sometimes.’

The manhole

On October 7 the first American cruise missiles struck Afghanistan, and on October 11 Elena flew safely back to London; and on October 31 I myself crossed the Atlantic. To spend a few days in Manhattan and then take the shuttle to Boston. I had hoped of course to see Christopher, but he was in the city of Peshawar on the Pakistani–Afghan border, at the head of the Khyber Pass…

‘Some of them are really fired up about it – none more so than Norman.’ Them, in this sentence, meant New York novelists, and Norman was of course Norman Mailer. ‘He wanted to start writing a long novel about 9/11 on 9/12.’

The speaker was a young publisher friend, Jonas. We were drinking beer in an empty dive on 52nd Street.

I said, ‘The urge soon passed, I bet. Norman’s too wise about the ways of fiction. Have you read The Spooky Art? He’ll wait. Something like this takes years to sink in.’

‘I’m told that Bret’ – Bret Easton Ellis, the rather blithely unsqueamish author of American Psycho – ‘is struck dumb. For now.’ ‘Well. Everyone’s responding in their, at their own…’

Jonas said, ‘We have a lady in Publicity who does the press ads? She reads the book, she reads all the reviews, and she assembles and arranges the quotes. She’s the best there is at that, and she’s eighty-three. Totally on the ball. And you know something? She can’t take it in. She was here – she saw what happened. But she doesn’t get what happened. “I can’t take it in,” she says. “It’s too big.” ’

‘…It’s too big.’

Three times I went downtown to what they were now calling the Pile.

My wife, in her piece,*7 wrote that Ground Zero made her think of a steaming manhole. A fourteen-acre manhole. When she was there, in late September, the double high-rise of the WTC had become a medium-rise – a rusted steel and rubbish heap stretching to twenty storeys (down from 110). Now, in early November, the medium-rise had become a low-rise, chewed at its periphery by excavators and various other mechanical dredgers and burrowers…

‘The unmentionable odour of death’ had lifted and dispersed. Later in Auden’s poem we read:

Into this neutral air

Where blind skyscrapers use

Their full height to proclaim

The strength of Collective Man…

Down at the Pile the air was no longer neutral (it was redolent of doused flames, scorched electrics, and the dusty undertaste of a lost battle); but the strength of collective man was never more palpable. Here the colossal squid of American can-do, American will-do, was fully engaged, with ironworkers, structural engineers, plumbers, pipefitters, boilermakers, cement masons, with cognoscenti of asbestos, of insulation, of sheet metal, riggers, truckers, teamsters…Like millions of others, worldwide, I had seen the Towers collapse in real time; and before me now the hundreds of hardhats were testifying to the weight of what came down.

…West 11th Street (I was staying there at my in-laws’, in the house where my wife was raised): on the corner of Sixth Avenue stood Ray’s Pizza, on the corner of Seventh stood St Vincent’s Hospital. When Elena was here both buildings were plastered with images of missing people: she read several hundred legends typed or scrawled beneath a candid face…Please call day or night if you have ANY information of ANY kind!!!!’ Elena wrote on:

The posters give us many details: this daughter has a mole beneath her left buttock, this husband has a KO tattoo on his left arm, as if they are wandering around in a daze somewhere and don’t know who they are. But they’re not. It is we who are wandering around in a daze.

And the lost will not be found. In total, three police officers, six firefighters, and eleven civilians were safely extracted from under the fused mass of the Pile, which contained approximately 2,700 dead bodies.

Chinatown

How was your trusted ex-girlfriend? asked Phoebe, drily, on the day of his return from Durham. She was well, he quietly answered. Lily was well in 1977 and she was well in 2001. They met for lunch on a Saturday in Chinatown.

Like Elena (and like Julia), Lily was an American who had spent much of her life in England. He had known her for forty years. So they talked about the past, and their marriages, and especially their children, and not just about September 11.

He had no reason to invoke that very congenial episode, up north. But he kept thinking of it while they ate. After the public event, the dinner, and the nightcaps in the hotel lounge, they went to her room and followed the dictates of muscle memory. Being faithful won’t do a damn thing for me (he’d briefly reasoned): I’ll be punished anyway…

Now they were talking about certain of their exes, and he said,

‘Remember Phoebe? I never grilled you, but what was your impression?’

‘Well I hated her at first of course because of her figure and the way she eats. But after that I took to her. She made me laugh.’

‘Really? I’m glad, because she didn’t get on that well with other women. And you’re usually wary of those men-only types.’

‘She made me laugh about your lunch with Roman Polanski. In Paris that time – when was that?’

‘It was later on. I think it was ’79. You know, Roman was born in Paris?’

‘Was he? And you found him so charming.’ Lily looked furtive and amused. ‘Did you hear what happened there?…Well, when you went to the bathroom, he slid his hand between her thighs and said, Get rid of him.’

‘…The dirty little bastard. What’d she say?’

‘She said, or she said she said, How can I get rid of him? He’s writing a huge piece about you and we’ve only been here five minutes. Then he gave her his phone number on a napkin and made her swear that she’d call him the next day.’

‘And did she?’

Lily shook her head. ‘That’s what I asked her. And I remember exactly. She said, Certainly not. He’d just jumped bail for drugging and buggering a thirteen-year-old. Perhaps I’m very old-fashioned, but I think that’s un peu trop, don’t you?’

He said, ‘You know, Polanski insisted that everyone wants to fuck young girls. The lawyers, the cops, the judge, the jury – they all want to fuck young girls. Everyone. I don’t want to fuck young girls. Any more than I want to fuck a pet rabbit or a puppy.’

‘But they do have a following, thirteen-year-olds.’

‘I suppose. No, clearly they do. Ooh, that dirty little bastard. He waits till I go to the bathroom, then he…’

Now it was Lily’s turn to go to the bathroom, and as Martin asked for the bill he thought about that breakfast in bed, at the Durham Imperial, and about the journey back by train: many hours to consider Phoebe’s past warnings and threats (Woe betide you), which never materialised. Now he paid.

‘What’s she up to these days, Phoebe?’ said Lily as they were heading out.

‘I happened to see her niece the other day. Who told me Phoebe was rich. She gave up her business for a big cheque.’

‘What was her business?’

‘I was never really clear about that. Business business. Brokering. She took early retirement. With bonuses. Business.’

‘She put the wind up me once. It was very soon after you saved my life in Durham. Phoebe gave me such a look. Like Lucrezia Borgia wondering how to flay me alive. Then she threw her head back and laughed and said, Oh never mind.’

Lily went south, and Martin walked north-west, through Chinatown and into Little Italy. The scents of a dozen different cuisines, as Elena had noted, and the sound of a dozen different languages: You can’t help thinking that the whole Taliban Council would go unnoticed walking down Canal Street…Across Houston, past NYU, up Broadway as far as the Strand Bookstore, then left to Sixth Avenue. Ray’s Pizza, no longer a would-be clearing house (no longer a kiosk thatched with photos and messages), but the locus of a neglected roadside shrine, keepsakes, scrawled farewells, and a little midden of petals, leaves, and stems.*8

Roman Polanski, like Father Gabriel – men so stirred by violation that only children would do. Now that Martin had young daughters of his own all his thoughts and feelings about Phoebe were changed, recombined utterly. He used to imagine that he had weighed it and assessed its mass: the weight of the early betrayal, the weight of what came down. But now he knew he’d had no idea.

Long shadows

The mood of all New Yorkers just now, as Elena put it, is of a huge self-help group – cooperative, communitarian, even socialistic. But on November 7, in the paper, there was an informal interview with a civic-minded activist who every morning for eight weeks had stood on a corner nearby (with a score of others) bearing a sign that said SANITATION ROCKS.

‘We were there to cheer the sanitation trucks as they passed by,’ he told the reporter. ‘But yesterday the truck passed by and when we cheered the driver gave us the finger. So I guess everything’s slowly getting back to normal.’

And normal New York was still tumultuous. A true-blue Monday afternoon, and I stood on Sixth Avenue looking for a cab to take me to LaGuardia; under a lowered sun the long-shadowed moneymen and moneywomen of Manhattan streamed by, getting and spending in a spirit of sharp-elbowed devotion to gain. This was the Village, I knew, and not the South Bronx, but still: no fighting, no biting, and never mind the great gamut of castes and colours and alphabets. All the passions and hatreds of the multitude – all the bitter furies of complexity – were delegated to the metal beasts of the road: barbarously impatient, subhumanly short-fused, squirming and jostling to find their place in the Gold Rush.

Saul won’t be like Iris, I was telling myself. Iris was slightly nuts in the first place (as was John Bayley).*9 Saul wouldn’t be reduced to saying ‘Where is?’ and ‘Must do go’. But why couldn’t Saul absorb September 11? ‘The history of the world’, he used to say, not solemnly but not unseriously, ‘is the history of anti-Semitism.’ And there was plenty of anti-Semitism intertwined with September 11.*10 It was just ‘too big’: it was the size of the event that made it unwieldy, when Saul tried to contain it. That was what I kept telling myself.

I stared at the red traffic light to my left on 11th Street. It looked to me like a Time magazine illustration of some newsworthy virus or bacterium, faceted like an insect’s eye, black-studded, and slightly hairy at the edges…

Repeatedly turning my head south, towards downtown (where the cabs were meant to be coming from), I saw that insistent void where the Twin Towers used to be. You wanted to avert your eyes from the helpless nudity of the air. Skyscrapers would never look the same, and planes would never look the same, and even the oceanic Manhattan blue, so intensely charged, would never look the same.

In the end I was driven to the airport, at appalling speed, by a certain Boris Vronski. Fitfully I read, but kept looking up and out…

What exactly did ‘political Islam’ have in mind? World hegemony and a planet-wide caliphate. Attained how? Necessarily by defeating all the infidel armies, the British, the French, the Indian, the Japanese, the Chinese, the North Korean, the Russian, and the American – the infidel armies, with their aircraft carriers and their trillion-dollar budgets. The restored Caliphate: God willing. Yes, God would need to be willing. And able. That which political Islam had in mind made no sense at all without the weaponry of God.

I was coming to the end of my book, Norman Cohn’s Warrant for Genocide (1967), a study of the Tsarist concoction The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (in the Middle East an evergreen bestseller, along with Mein Kampf). Now I turned to the foreword (added in 1995) and read:

There exists a subterranean world where pathological fantasies disguised as ideas are churned out by crooks and half-educated fanatics [notably the lower clergy] for the benefit of the ignorant and the superstitious. There are times when this underworld emerges from the depths and suddenly fascinates, captures, and dominates multitudes of usually sane and responsible people, who thereupon take leave of sanity and responsibility. And it occasionally happens that this underworld becomes a political power and changes the course of history.*11

At Delta Shuttle I climbed out, confirmed that the Trump Shuttle was no more, and bought a ticket for the forty-minute flight to Logan.

*1 Christopher told me there was a WMD scare in Washington: it got around that a rogue nuclear weapon was poised to vaporise the capital. Some friends were urging the Hitchenses to leave town – urging in vain.

*2 For instance, I was secretly spending a lot of time with Philip Larkin: the Collected Poems, the Selected Letters, and Andrew Motion’s authorised Life. Although I knew these books well (I had written about them at great length in 1993), two main themes came at me with all the force of discovery…First, Philip’s father. Not many pages ago I called Sydney Larkin a fascist. That word was often used loosely in my time (parking wardens were called fascists), so it might help to be more specific. Sydney wasn’t a fascist, or only secondarily. He was something much more advanced. What he was was a Nazi. This remains a startling – and startlingly underexamined – truth: Philip had been raised and mentored by an adherent of Adolf Hitler…But what I kept thinking about, what I kept returning to, was the destitution – the irreducible church-mouse penury – of Philip’s lovelife.

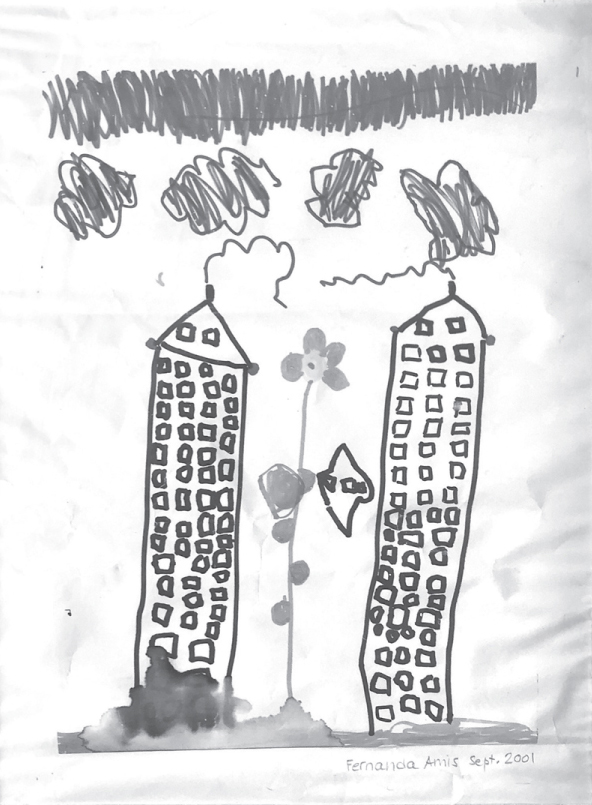

*3 Inez was two; so in her infinite book of secrecy only a little could I read. Maybe she seemed vague in distinguishing the falling towers from the US Open (or maybe she thought ‘tennis’ meant ‘television’), but she certainly registered the new atmosphere, the sudden congealing of mood in everyone around her…Eliza, almost five, was more

transparent (see above): the plane, hauntingly, looks more like a Stealth Bomber (or a flying saucer) than a 767; and notice how the black smoke is leniently attributed to the WTC’s chimneys. That flower is all her own (with perhaps a nod to ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’)…When they spoke of the event, Bobbie, Nat, and Gus, all three of them respectful students of history, lowered their voices and their gazes, no doubt already aware that the political consequences would dominate much of their early lives. The Amises were all doing what they could with September 11. Elena, protective and also pugnacious in the name and the spirit of New York City, where she was born and raised, wanted to ‘go home soon’ (and soon did).

*4 The rebel angel Belial, consigned to Pandemonium (‘place of all demons’), puts it simply enough (Paradise Lost, Bk II): ‘For who would lose, / Though full of pain, this intellectual being, / Those thoughts that wander through eternity…?’ Alzheimer’s, like populism, is decidedly philistine; it hates the intellectual being.

*5 Bin Laden would have points of agreement with Noam Chomsky and Gore Vidal. His true soulmate, though, would be Jerry Falwell: ‘the pagans, the abortionists and the gays and the lesbians…all of them have tried to secularise America. I point the finger in their face and say, “You helped this happen” ’…This line of reasoning always makes me think of two lines from ‘Leda and the Swan’. Yeats’s sonnet begins with an act of bestiality and rape: Zeus in animal disguise ravishes and impregnates the nymph Leda; and that child will be Helen of Troy. ‘A shudder in the loins engenders there / The broken wall, the burning roof and tower…’

*6 This comes in the seventh chapter – the one that begins: ‘I am now faced with the distasteful task of recording a definite drop in Lolita’s morals.’ Humbert is instituting a regime of sexual bribes. Nabokov continues: ‘O Reader! Laugh not, as you imagine me, on the very rack of joy noisily emitting dimes and quarters, and great big silver dollars like some sonorous, jingly and wholly demented machine…’ Lolita is described as ‘a cruel negotiator’. Phoebe was not a squeezer or a gouger; she was more like a cheerful auctioneer. And there were other differences. I wasn’t a stepfather, I wasn’t in loco parentis. And Phoebe was thirty-six, not thirteen.

*7 Which ran in the Guardian on October 11. An expanded version appeared soon afterwards in the American Scholar.

*8 Flowers, somehow, are universally felt to propitiate death. Even Eliza, not quite five, understood this…On another autumn afternoon, in 2015, I stood outside the Bataclan in Paris: candles, letters (‘Cher Hugo’), unopened bottles of wine, empty bottles of beer, and bushels of flowers, sheathed in sweating cellophane.

*9 They were the kind of people who like getting ill and like getting old. They preferred winter to summer and autumn to spring (yearning, as John wrote, for ‘grey days without sun’). In company the Bayleys were both high-spirited and dreamy; their love of grey days was aesthetic, not neurotic…On the other hand, Iris and John were also truly incredible slobs. ‘Single shoes [and single socks] lie about the house as if deposited by a flash flood…Dried-out capless pens crunch underfoot.’ As for the housework: in the past ‘nothing seemed to need to be done’, and now ‘nothing can be done’. At the Bayleys’, the bath, so seldom used, has become ‘unusable’, and even the soap is begrimed…Saul was a Jew and not entirely non-observant (there were occasional prayers and rituals and I would don a beenie); and he was strict about cleanliness…No, I thought, Saul won’t be like Iris. He wouldn’t be out prospecting for pebbles and pennies in the gutters; he wouldn’t be watching Teletubbies; he wouldn’t be saying to his spouse, ‘Don’t hit me.’

*10 The right answer to the question ‘How many Jews were in the WTC on September 11?’ is ‘Why do you want to know?’ Among the wrong answers is ‘None’. This was widely believed or at least touted by Judaeophobes, conspiracists, and huge pluralities in the Middle East. There were many Jews in the WTC and many died there. The numbers given seem to me surprisingly various (perhaps reflecting decent disquiet at the thought of any ‘Jew Count’), but the median figure is 325.

*11 In the fifteen years following 2001, about 750 Americans were killed by lightning strikes; in the same period, 123 Americans were killed by Islamists (accounting for one-third of 1 per cent of national murders: 240,000). Another database finds that ‘over 80 per cent of all suicide attacks in history’ have taken place since September 11; and the victims are very predominantly Muslim (estimates range ‘between 82 and 97 per cent’). In 2015 there were 11,774 terrorist attacks worldwide, with 28,328 victims; that year in the US, Islamist terrorism killed nineteen people, two fewer than those killed by toddlers who got their hands on household guns…It would seem to follow that any generalised fear of Muslims – and all talk of a Third World War or even ‘a clash of civilisations’ – is caused either by delusion or by political opportunism. A terrorist WMD will remain a possibility, but September 11 is already unrepeatable (in other words, the culmination came first, and out of a clear blue sky). Islamism has indeed changed the course of history, by scarring it with additional wars. For the West the lesson is this: the real danger of terrorism lies not in what it inflicts but in what it provokes.