Chapter 5

And say why it never worked for me

‘Now you can’t ever ask her,’ Elena had said one morning out of the blue, in 2010.

It was a few days after Hilly’s death, so Martin could easily fill in the spaces: Now you can’t ever ask your mother if by any chance Philip Larkin knocked her up in December 1948.

‘That’s right,’ he said. And he was glad. It was the only solace he would ever get from his orphanhood. ‘Now I can’t ever ask her.’

The book in your hands calls itself a novel – and it is a novel, I maintain.

So I want to assure the reader that everything that follows in this chapter is verifiably non-fiction.

The doll on the mantelpiece

1. ‘Germany will win this war like a dose of salts, and if that gets me into gaol, a bloody good job too.’ Philip Larkin, December 1940 (aged nineteen).

2. ‘If there is any new life in the world today, it is in Germany. True, it’s a vicious and blood-brutal kind of affair – the new shoots are rather like bayonets…Germany has revolted back too far, into the other extremes. But I think they have many valuable new habits. Otherwise how could D.H.L.*1 be called Fascist?’ July 1942.

3. ‘Externally, I believe we must “win the war”. I dislike Germans and I dislike Nazis, at least what I’ve heard of them. But I don’t think it will do any good.’ January 1943 (aged twenty-one).

These sentences, notable for their moral defeatism (disguised in the first quote as gruff immunity to illusion), their ignorance, and their incuriosity, come from the early pages of the Selected Letters of Philip Larkin (1991). So here we confront a youth turning twenty who ‘dislikes’ Nazis (or at least what he’s heard of them). By January 1943 he might have heard of what we now call the Holocaust (‘probably the greatest mass slaughter in history’, as the New York Times reported in June 1942). Did he hear of it later on? Neither in his correspondence nor in his public writings is there a single reference to the Holocaust – not one, in his entire life.*2

Philip’s father, Sydney Larkin, OBE, who somehow acquired a reputation for intellectual rigour, was a self-styled ‘Conservative Anarchist’; he was also a zealous Germanophile. He went on being pro-German even after September 1939 – and even after November 1940, and even after VE Day in May 1945…In November 1940 more than 400 German bombers descended on Sydney’s hometown of Coventry, destroying the city centre, where he worked (as a senior municipal accountant), the fifteenth-century cathedral, nine aircraft factories, and much else; the raid wounded 865 and killed 380. The Luftwaffe raids began in August 1940 and continued until August 1942 (with a final death toll of over 1,200). And Sydney went on being pro-German.

Before the war, in 1936 and again in 1937, Sydney took his only son along with him on one of his regular pilgrimages to the Reich: consecutive summer holidays, the first in Königswinter and Wernigerode, the second in Kreuznach (so both trips saw a rare omission for Syd: no Nuremberg Rally, with its 140,000 kindred souls). As Philip wrote, much later (in 1980), when the facts of Sydney’s affiliation were about to be drawn attention to in a PL Festschrift:

On the question of my father and so on, I do think it would be better to say ‘He was an admirer of contemporary Germany, not excluding its politics.’ In fact he was a lover of Germany, really batty about the place.

Nowhere is it written that Sydney was an anti-Semite.*3 But how could it have been otherwise, for an admirer of the politics of Nazi Germany?

One wonders what else he liked about the place. A serious and compulsive reader (with a particular affection for Thomas Hardy, on whom he once gave a public lecture), Sydney was not in any ordinary sense a philistine; and he would have felt the weight and glamour of German literature and German thought.

But the Third Reich immediately presented itself as a regime of book-burners. Old Syd lamely admired Germany’s ‘efficiency’ and its ‘office methods’ (in fact the Nazi administration was always drowning in chaos). Did these supposed pluses outweigh the Reichstag Fire terror, the Jewish boycott, the gangsterish purge of the Brownshirts, the Nuremberg Laws, the state-led pogrom known as Kristallnacht, the rapes of Czechoslovakia and Poland, and the Second World War?

Although the discriminatory legislation was already in place, the summer of 1936 – when père et fils paid their maiden visit – saw a brief intermission for Germany’s Jews. It was the year of the Berlin Olympics; and so the country Potemkinised itself for the occasion. Formerly there had been printed or painted signs, in hotels and restaurants and suchlike (NO JEWS OR DOGS) but also on the approach roads of various towns and villages, saying JEWS NOT WELCOME HERE. These were tastefully removed for the Games (the first ever to be televised). Afterwards, of course, the signs were re-emplaced.

It is said that Sydney had on his Coventry mantelpiece a moustachioed figurine which, at the touch of a button, gave the familiar salute. There was evidently nothing in the fascist spirit that Sydney didn’t warm to: the menacing pageantry, the sweaty togetherness (he

‘liked the jolly singing in the beer cellars’), the puerile kitsch of the doll in the living room.

A sense of danger, a queer, bristling feeling of uncanny danger

In a diary entry for October 1934 Thomas Mann praised the ‘admirably insightful letter by Lawrence, about Germany and its return to barbarism – [written] when Hitler was hardly even heard of…’ D. H. Lawrence’s ‘Letter from Germany’ was published, posthumously, in the New Statesman; but it was written six years earlier, in 1928, when the author was forty-two (and already dying).

Now Lawrence harboured many deplorable opinions and prejudices, including a cheaply unexamined strain of anti-Semitism: ‘I hate Jews,’ he wrote in a business letter; and even in the fiction Jewry is his automatic figure for cupidity and sharp practice. Indeed, the critic John Carey, in his essay ‘D. H. Lawrence’s Doctrine’, concludes: ‘the final paradox of Lawrence’s thought is that, separated from his…wonderfully articulate being, it becomes the philosophy of any thug or moron.’

But that articulacy, that penetration, could sometimes approach the miraculous. Lawrence spoke German and was married to a German (Frieda von Richthofen); and he had a real grasp of the central divide in German modernity: the divide between the tug to the west and the tug to the east, between ‘civilisation’ and ‘culture’, between progressivism and reaction, between democracy and dictatorship (for a retrospective, see Michael Burleigh’s Germany Turns Eastwards). Sydney went there in the late 1930s and had no sense that anything was wrong – at a time when most visitors found its militarised somnambulism ‘terrifying’. Lawrence went there in 1928 and showed us what the human antennae are capable of:

It is as if the life had retreated eastward. As if the German life were slowly ebbing away from contact with western Europe, ebbing to the deserts of the east…The moment you are in Germany, you know. It feels empty, and, somehow menacing…

[Germany] is very different from what it was two and a half years ago [1926], when I was here. Then it was still open to Europe. Then it still looked to Europe, for a sort of reconciliation. Now that is over. The inevitable, mysterious barrier, and the great leaning of the German spirit is once more eastward, towards Tartary.

…Returning yet again to the destructive East, that produced Atilla…But at night you feel strange things stirring in the darkness, strange feelings stirring out of their still-unconquered Black Forest. You stiffen your backbone and listen to the night. There is a sense of danger…Out of the very air comes a sense of danger, a queer, bristling feeling of uncanny danger.

1928, not 1933. Not 1939, and not 1940 – by which time the exiled historian Sebastian Haffner was writing Germany: Jekyll and Hyde, where he came to the following conclusion:

This point must be grasped because otherwise nothing can be understood. And all partial acquaintance is worthless and misleading unless it is thoroughly digested and absorbed. It is this: Nazism is no ideology but a magic formula which attracts a definite type of men. It is a form of ‘characterology’ not ideology. To be a Nazi means to be a type of human being.

And the National Socialist Weltanschauung ‘has no other aim than to collect and rear this species’: ‘Those who, without pretext, can torture and beat, hunt and murder, are expected to gather together and be bound by the iron chain of common crime…’

And this is the ethos Sydney Larkin ‘admired’ or was ‘really batty about’; this is the ethos his son cautiously ‘disliked’.

And yet Philip Larkin, despite the crash in his reputation when the Letters and the Life came out (‘racism’, ‘misogyny’), would deservedly – and inevitably – emerge as ‘Britain’s best-loved poet since the war’. It was a war, by the way, in which he played no part. In December 1941 PL was summoned to his medical. According to Andrew Motion, he ‘made no secret of his hopes that he would fail’. And he did fail. Eyesight.

The PL of this period – a flashy dresser and a charismatic talent who for a while felt socially bold – was trying to sound insouciant; but he was at all other times a sincere patriot, and so he felt humbled and unmanned and above all confused. Floundering and posturing to the last, showing every attribute of youth except physical courage (and now seeking safety in numbers), PL wrote, ‘I was fundamentally – like the rest of my friends – uninterested in the war.’

Eva, Philip, Sydney, Kitty

Like the rest of his friends? Did he mean the ones who were in the army? Kingsley, for instance, who passed through France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany (in 1944–5), was interested in the war. For one thing he was interested in surviving it; and as a Communist as well as a Britisher, he would have been ideologically and emotionally interested in winning it. (Kingsley was trained as an infantryman, but he was destined for the Signals and he never fired a shot.) In his version of Machtpolitik, KA hoped for the shoring up of Stalin. Now reread the three quotes with which this section began, and then try to evade the likelihood that PL hoped for the shoring up of Hitler.

Q: What could have steered the tremulous undergraduate into this morbid and forsaken cul-de-sac? A: Having a father like Sydney (and being very young).

When it was all so obvious. Even the most reactionary writer in the English canon, Evelyn Waugh, saw the elementary simplicity of September 1939. As Guy Crouchback, the hero of the WW2 trilogy Sword of Honour, puts it:

He expected his country to go to war in a panic, for the wrong reasons or for no reason at all, with the wrong allies, in pitiful weakness. But now, splendidly, everything had become clear. The enemy at last was plain in view, huge and hateful, all disguise cast off…Whatever the outcome there was a place for him in that battle.

This much had long been clear to everybody: Naziism meant war (and for its enemies a just war par excellence). And, when war came, what type of young man would scorn a place in it – any place whatever?

Tyrants of mood don’t hug and kiss

Sydney Larkin was ‘unrepentant’ about many things, including his views on women. ‘Women are often dull, sometimes dangerous and always dishonourable’ was a personal aphorism he cherrypicked for his diary. And this was another set of attitudes that his son, as a tyro adult, found himself dutifully echoing: ‘All women are stupid beings’; they ‘repel me inconceivably. They are shits.’

Larkin Sr made his daughter’s ‘life a misery’, and over the years reduced his wife, Eva, to a martyred drizzle of anxiety and timorousness. ‘My mother’, PL wrote, ‘is nervy, cowardly, obsessional, boring, grumbling, irritating, self pitying.’ Sydney’s life was short; Eva’s was long. ‘My mother,’ PL resumed, decades later, ‘not content with being motionless, deaf and speechless, is now going blind. That’s what you get for not dying, you see.’ Nevertheless, PL was thoroughgoingly filial, as we’ll see.

In his office Sydney was always keen for a ‘cuddle’ with female subordinates, ‘not missing an opportunity to put an arm round a secretary’, as an assistant reminisced.*4 He was in addition the kind of patriarch, dourly typical of mid-century England, who set the emotional barometer for those around him – for all those within range.

As a child I had several friends with this kind of father. They were the mood tyrants. Brooding, frustrated, rancorous, intransigent, their will to power reduced to the mere furtherance of domestic unease. And these household gods all held sway over the same kind of household – the prized but intimidated sons, the warily self-effacing daughters, the mutely tiptoeing spouses, the cringeing, flinching pets…

Aged thirteen, after a weekend spent in the rain-lashed bungalow of just such a mood tyrant (the father of my best friend Robin), I cycled home to Madingley Road, Cambridge, parked my bike in one of the two outbuildings that housed our Alsatian, Nancy, and her recent litter, and our donkey, Debbie, then entered by the back door, stepping over one of our eldest cats, Minnie. Going in, I felt – I now suppose – like PL going out:

When I try to tune into my childhood, the dominant emotions I pick up are, overwhelmingly, fear and boredom…I never left the house without the sense of walking into a cooler, cleaner, saner and pleasanter atmosphere.

But a happy child is no better than a gerbil or a goldfish when it comes to counting its blessings, and as I sauntered into the convivial kitchen I experienced no rush of gratitude towards my warmly humorous and high-spirited parents. I was home: that was all. I was in the place where – while it lasted – I was unthinkingly happy.

‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad.’ This is the most famous line in Larkin’s corpus – partly, no doubt, because it was a near-universal tenet of the time (and seemed to be the starting point of all psychiatry). In principle Philip agreed that ‘blaming one’s parents’ led nowhere, or rather led everywhere (‘If one starts blaming one’s parents, well, one never stops!’); but he went on:

[Samuel] Butler said that anyone who was still worrying about his parents at 35 was a fool, but he certainly didn’t forget them himself, and I think the influence they exert is enormous…What one doesn’t learn from one’s parents one never learns, or learns awkwardly, like a mining MP taking lessons in table manners or the middle aged Arnold Bennett learning to dance…I never remember my parents making a single spontaneous gesture of affection towards each other…

With PL, in any event, fondness failed to flow. ‘I never got the hang of sex anyway,’ he gauntly clarified in another letter to Monica Jones. ‘If it were announced that all sex wd cease as from midnight on 31 December, my way of life wouldn’t change at all.’ That was written on December 15, 1954. ‘Sexual intercourse began / In nineteen sixty-three,’ runs Larkin’s most famous couplet; but for him and Monica it was already withering away – in their early thirties. And yet they trundled on until 1985, when Philip died, aged sixty-three: his final hommage to Sydney.

PL never saw his parents hug and kiss. I and my siblings often saw our parents hug and kiss (and we responded with a mid-century version of what my younger daughters now say when they see their parents hug and kiss: ‘Get a room’). But as I tittered, and blushed (blushed hotly and richly), a necessary transfusion was somehow taking place; I was seeing my mother and father as autonomous individuals, going through the rituals of their own affinity – their own affair. A child axiomatically needs to be the recipient of love; and a child also needs to witness it.

‘I read your Larkin piece. Twice,’ I said on the phone (New York–Washington, in the spring of 2011).*5 ‘Full of good things.’ And I listed some of them. ‘God, though, he’s an impenetrable case, don’t you find?’

‘Oh, yeah. The poems, they’re as clear as day, they’re…pellucid, but humanly he’s a labyrinth. You get lost in him.’

‘That famous aside of his, you quote it – deprivation is for me what daffodils were to Wordsworth. So he liked deprivation because it stirred his muse.’

‘Yes, and sometimes making you wonder whether he went looking for it.’

‘But he means romantic deprivation. And how d’you go looking for that?’

‘Especially when you’ve already got it. No one’s that dedicated. And anyway, in this instance I’d say deprivation came from within.’

‘You quote that other line he…Here it is. Sex is always disappointing and often repulsive, like asking someone else to blow your own nose for you. Blow your nose?’

‘Blow your nose? Now there he shows real prowess of perversity.’

‘You know, I get surer and surer that that’s a big part of the Larkin fascination. The purity of the poems. And then the mystery story, the whodunnit of his – of his murk.’

‘It’s all Sydney, don’t you think? That Komodo dragon in the living room.’

‘Mm…Brother, we’ll talk. Now. When are you getting here?’

‘I’m aiming for Friday afternoon. Around drinks time.’

‘What could be more agreeable?’

‘Oh, tell me something. You miss the old country, I know. I don’t expect to miss England but I’m sure I’ll miss the English. It’s that tone, that tone of humorous sympathy. Americans are nice too, individually, but you couldn’t call them droll.’

‘No. Tocqueville said that humour would be bred out of them by sheer diversity. Anything witty was bound to offend someone. He thought they’d reach the point where nobody’d dare say anything at all.’

…This could wait for the weekend, but the Hitch was in fact under a serious misapprehension about Philip’s father. He was right about the dragon in the living room: that was Sydney, a reliably unnerving man. What he got dead wrong was how Philip felt about him.

Every man is an island

During his time at Oxford (1940–3) Larkin briefly kept a dream journal, whose contents are summed up by Motion:

Dreams in which he is in bed with men (friends in St John’s [his college], a ‘negro’) outnumber dreams in which he is trying to seduce a woman, but the world in which these encounters occur is uniformly drab and disagreeable. Nazis, black dogs, excrement and underground rooms appear time and time again, and so do the figures of parents, aloof but omnipresent.

Excrement, black dogs – and Nazis…But as it happens Larkin’s sexuality, seen from a safe distance, managed a reasonable imitation of normality. After a slow start, and many snubs and hurts, there was always a proven partner nearby, and we know a fair bit about what he got up to and with whom. All the same, the eros in him is still mysterious and very hard to infiltrate. It is indeed a maze, or a marshland with a few slippery handholds. And yet, as we wade through it all, we gratefully bear in mind that this – somehow or other – was Larkin’s path to the poems.

To repeat: as a young man Larkin was intrigued, or better say fatally mesmerised, by the Yeatsian line about choosing between ‘perfection of the life’ and perfection ‘of the work’. But that was a line in a poem (‘The Choice’), not in a manifesto; no one was supposed to act on it (and Yeats certainly didn’t). Larkin seized on the either/or notion, I think, as a highminded clearance for simply not bothering with the life, and settling instead for an unalloyed devotion to solitude and self. As he put it in ‘Love’ (1966): ‘My life is for me. / As well ignore gravity.’ Most crucially, the quest for artistic perfection coincided with his transcendent worldly goal – that of staying single.

‘Sex is too good to share with anyone else,’ Larkin half-joked, early on. Yet he found that the DIY approach to romance was always overcome by a prosaic need for female affection and support. And so there were lovers, five of them: Ruth, Monica, Patsy, Maeve, and Betty.*6 Larkin’s affairs were not evenly spaced out over the thirty-odd years of his ‘active life’. They came in two clusters: Monica overlapped with Ruth and Patsy, in the early 1950s, and she overlapped with Maeve and Betty, in the mid-1970s. This pair of triads represented the twin peaks of Larkin’s libido, which was otherwise conveniently docile (‘I am not a highly sexed person,’ as he kept having to remind Monica).

Ruth was sixteen when he met her in 1945, ‘a prim little small town girl’, as she phrased it; two years later they became lovers and were briefly engaged. Monica, the mainstay, was an English don at Leicester (and we’ll be spending an evening with her later on). Patsy was the only red squirrel in this clutch of grey Middle-Englanders; a highly educated poet and rather too thoroughgoing free spirit, Patsy died when she was forty-nine (‘literally dead drunk’, as PL noted). Maeve, a quasi-virgin of a certain age, a faux naïf, and a true Believer (who, post mortem, tried to enlist PL’s godless spectre for the Catholic Church), was on the clerical staff at Hull. As was Betty, who, until Larkin made his sudden move, had been his wholly unpropositioned and unharassed secretary for the previous seventeen years.

Of the five, Betty had the considerable virtue of being ‘always cheerful and tolerant’: i.e., she was a good sport. Ruth, Patsy, Maeve, and overarchingly Monica were not good sports. According to my mother (and nothing in the ancillary literature contradicts her), these women were alike curiously unrelaxed and unrelaxing, oppressed – most likely – by class anxieties and inhibitions that we would now find merely arcane. In addition they all gave off a pulse of entitled yet obscurely injured merit, of vague and tetchy superiority – a superiority quite unconfirmed by achievement; Monica, a noisily opinionated academic all her adult life (but also a close reader, and now and then a trusted editor of Larkin’s verse), never published a word…

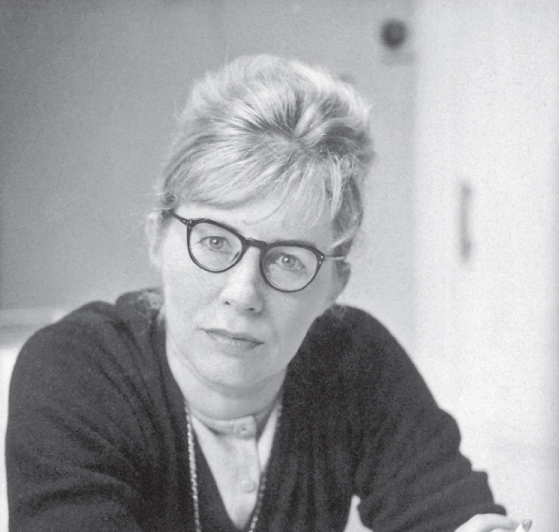

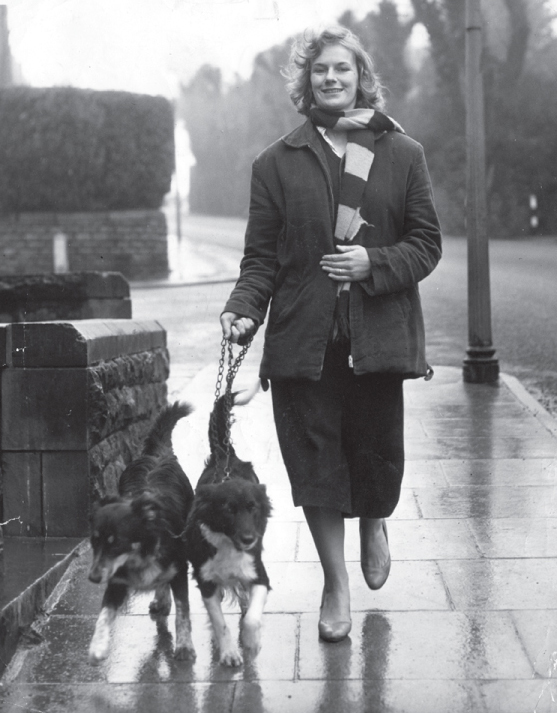

Ruth Bowman

Monica Jones

Patsy Strang

Maeve Brennan

Betty Mackereth

Hilly Bardwell

As well as being rich and worldly (she studied at the Sorbonne) Patsy was artistic, and her prickliness took more highbrow form (Kingsley said she was ‘the most uninterestingly unstable woman’ he had ever met). Philip’s liaison with her was manageable and brief (and he was touchingly grateful to have had it). But she scared the life out of him a decade later, drunkenly materialising in Hull – muzzy, weepy, utterly disorganised (wanting to stay the night and accusing him of ‘not being continental’)…As PL admitted, his women inclined towards the ‘neurotic’ and the ‘difficult’, and also the ‘unattractive’. He summed them up himself, in four lines of wearily illusionless verse (quoted below).

Ruth, Patsy, Maeve, Betty – and Monica. His triangulations involved dramas, tears, scenes, twenty-page letters, and decathlons of guilt and reproach – more than enough grief, you’d have thought, to fuel a typical marriage. When Monica was told about Maeve she was physically sick, and soon lapsed into near-clinical depression. The best proof of how much his girlfriends meant to Larkin was his willingness to shoulder – or at least outwait – their episodes of suffering while he had his way.

All this was interspersed with a great deal of yearning, brooding, coveting, fuming, and dreaming, not to mention a great deal of ‘wanking in digs’ (as he put it to a ladyfriend). Larkin had an extra-strong passion for pornography and kept a cache of it in his office (‘to wank to, or with, or at’, as he put it to another ladyfriend). But he was far less blithe or brazen when he went foraging for the blue stuff in red-light London, no doubt because in Soho he was pursuing more specialised tastes (schoolgirls, flagellation). Often the size of the trespass overcrowed him; he would ‘funk it’, and just shuffle away.

The loss of nerve, the withdrawal: it gives us the flavour of the Larkin frustration and the Larkin thwartedness. With lowered head he slips out of the dark sex shop (the bachelors’ bazaar) and into the rain, leaving that copy of Swish unmolested on its shelf as he creeps away, hugging to himself the familiar failure…

Invidia

In July 1959 Kingsley returned from an extended teaching job in America, and wrote to PL about his hyperactive success with the women of Princeton, New Jersey. A few months later Philip completed ‘Letter to a Friend About Girls’ (which he never published). The ‘friend’ of the title is only approximately Kingsley, just as the narrator of the poem is only approximately Philip; but approximation can come very close. The poem begins:

After comparing lives with you for years

I see how I’ve been losing: all the while

I’ve met a different gauge of girl from yours.

Grant that, and all the rest makes sense as well:

My mortification at your pushovers,

Your mystification at my fecklessness –

Everything proves we play in separate leagues.

More than once Kingsley said to Philip: it wasn’t that they met different grades of girl; it was that they met all girls differently. They both had charm, but Kingsley’s was the charm of confidence, and Philip’s the charm of uncertainty; and it remains a maddening truth that both sexual success and sexual failure are steeply self-perpetuating. Philip knew all this, but in the poem the ‘I’ feigns ingenuousness, and evades the really embittering recognition: it wasn’t a case of ‘a different gauge of girl’; as Larkin acknowledged to Anthony Thwaite, it was a case of a different gauge of man. Still, the wretchedness he backs away from is quietly evoked.

Having listed some of the addressee’s ‘staggering skirmishes’ with wives, students, and (it seems) passers-by, Philip goes on: ‘And all the rest who beckon from that world…where to want / Is straightway to be wanted…A world where all nonsense is annulled, // And beauty is accepted slang for yes.’ In honing that last line Larkin must have wondered what it was in himself that qualified as accepted slang for no.

There was another reason why Philip kept ‘Letter to a Friend’ in his bottom drawer. As he very reasonably wrote (again to Thwaite), ‘it would hurt too many feelings’; ‘If it were simply a marvellous poem, perhaps I might be callous, but it’s not sufficiently good to be worth causing pain.’ So it was only in 1988, with the publication of the rather overamplified – and of course posthumous – Collected Poems, that Ruth, Monica, Maeve, and Betty came to read the following (note the resignedly slow rhythms of lines two to five), as the poet summons his women:

But equally, haven’t you noticed mine?

They have their world, not much compared with yours,

Where they work, and age, and put off men

By being unattractive, or too shy,

Or having morals – anyhow, none give in:

Some of them go quite rigid with disgust

At anything but marriage…

you mine away

For months, both of you, till the collapse comes

Into remorse, tears, and wondering why

You ever start such boring barren games…

We can see why Philip was reduced to thinking that sex was too good to share with anyone else. Autoeroticism, for Larkin, wasn’t just a stopgap, an improvised faute de mieux. It answered something fundamental not only in his life but also in the workings of his art. ‘I don’t want to take a girl out, and spend circa £5 when I can toss off in five minutes, free, and have the rest of the evening to myself.’ And, as he wrote to his parents as early as 1947 (when Sydney was still alive), ‘tonight I shall stay in and write. How beautiful life becomes when one’s left alone!’

Something that might be described as ‘positive’ happened to Kingsley a year before he left for America. In response to it Philip wrote (to Patsy):

[It] has had the obvious effect on me. I am a corpse eaten out with envy, impotence, failure, envy, boredom, sloth, snobbery, envy, incompetence, inefficiency, laziness, lechery, envy, fear, baldness, bad circulation, bitterness, bittiness, envy…

And what was this supposed coup of KA’s? His ‘appearance on Network 3 on jazz’ – ‘the first of six programmes’, as Philip moodily adds.

If he felt that way about Network 3 (a radio subchannel devoted to hobbies), how would he feel about this? Just back from Princeton and his lucrative professorship in creative writing (July 1959), Kingsley writes to Philip and apologises for his year-long silence:

…I can plead that I wrote no more than four personal letters the whole time I was away…[and] that for the first half of my time there I was boozing and working harder than I have ever done since the Army, and that for the second half I was boozing and fucking harder than at any time at all. On the second count I found myself at it practically full-time.

By December of that year Philip had completed ‘Letter to a Friend About Girls’.

‘Empathy’ is not as slimy a word as ‘closure’, but it still comes mincingly off the tongue. Even so, Kingsley, here, shows lack of empathy to an almost vicious degree; erotic success is a kind of wealth, after all, and here he is, fanning his wad at a pauper…As we turn to Philip we may say that envy is an offshoot of empathy: from L. invidia, from invidere, from in- ‘into’ and videre ‘to see’. See into. Envy is negative empathy, it is empathy in the wrong place at the wrong time. Satisfyingly, too, ‘envy’ also derives from invidere, ‘regard maliciously’. It is not surprising that PL, much of the time, hated KA.

By all means empathise with the less fortunate, and do so with every consideration. But be careful. Don’t feel your way into the lives of the luckier. If you’re Philip, don’t ‘see into’ Lucky Jim.

We began with three snippets about politics; let’s start winding up with three snippets about sex. The first comes from a letter to Monica, the second from a letter to Kingsley. To which of the two is the third letter addressed, would you say?

-

I think – though of course I am all for free love, advanced schools, & so on – someone might do a little research on some of the inherent qualities of sex – its cruelty, its bullyingness, for instance. It seems to me that bending someone else to your will is the very stuff of sex…And what’s more, both sides would sooner have it that way than not at all. I wouldn’t. And I suspect that means not that I can enjoy sex in my own quiet way but that I can’t enjoy it at all. It’s like rugby football: either you like kicking & being kicked, or your soul cringes away from the whole affair. There’s no way of quietly enjoying rugby football. (1951)

-

Where’s all this porn they talk about?…[In Hull] it’s all been stamped out by the police with nothing better to do. It’s like this permissive society they talk about: never permitted me anything as far as I recall. I mean like WATCHING SCHOOLGIRLS SUCK EACH OTHER OFF WHILE YOU WHIP THEM, or You know the trouble with old Phil is that he’s never really grown up – just goes along the same old lines. Bit of a bore really. (1979)

-

It seems to me that what we have is a kind of homosexual relationship, disguised. Don’t you think yourself there’s something fishy about it? (1958)

In the first quote PL declares himself a sexual pacifist or vegan, and seems rather proud of his hypersensitivity (well ‘I wouldn’t’). In the second quote he gives a middleaged (and clearly very drunken) airing to his fantasy about caning schoolgirls, which dates back to his youth. The third quote appears in a letter to Monica. I’ve tried often, but I still don’t understand it. What can it mean? That he, PL, wasn’t very masculine and that she, MJ, wasn’t very feminine? And that they were in-betweeners of the same gender?

Anyway, peculiar, eccentric, innovatory, without any known analogues – you might even call it sui generis.

In a late letter PL observed of the poetry critic Clive James, ‘Just now and again he says something really penetrating: “originality is not an ingredient of poetry, it is poetry” – I’ve been feeling that for years.’

When poets go into their studies, they seek – or more exactly hope to receive – the original. Be original in your study. But not in your bedroom. It is like sanity: your hope, in these two departments, is to be derivative. You don’t want to be out there all on your own.

Violence a long way back

In only one (very late) poem did Philip attempt an explanation of what we may call his erotic misalignment. It comes in the alarmingly gloves-off ‘Love Again’ (1979), which begins as a lyric of violent sexual jealousy – not sexual envy, sexual jealousy:

Love again, wanking at ten past three

(Surely he’s taken her home by now?),

The bedroom hot as a bakery…

Someone else feeling her breasts…

But then just over halfway through this eighteen-liner the poet turns pointedly inward. ‘Isolate rather this element’, he soliloquises,

That spreads through other lives like a tree

And sways them on in a sort of sense

And say why it never worked for me.

Something to do with violence

A long way back, and wrong rewards,

And arrogant eternity.

The last three lines at first feel unyieldingly condensed. ‘Arrogant eternity’, we suppose, refers to the demands of art and to the brevity of the human span; ‘wrong rewards’, we suppose, refers to the haphazard allocation of luck, talent, sex, happiness, and (perhaps) literary recognition. But ‘violence / A long way back’? Motion persuasively argues that PL is not referring to actual abuse but to the ‘smothering nullity’ of his parents’ marriage: ‘they showed him a universe of frustration [and] suppressed fury…which threatened him all his life, and which was indispensable to his genius.’ All true; but I think we can go a little further than that.

In La Tomate off Dupont Circle I said (April 2011), ‘You refer to Syd as Larkin’s “detested father”. Would it were so, O Hitch. That would’ve made for a much simpler story. But Philip loved him.’

‘…Mart, you stagger me. That old cunt?’

‘He loved and honoured that old cunt. It’s all very fresh in my mind I’m afraid.’

‘Mm, I suppose you know more about it than you want to know. Thanks to Phoebe.’

I sighed and said, ‘I was having to think of Syd as my…’

‘Christ, I do see…But there’s nothing about Syd in Letters to Monica.’

‘Just this – “O frigid inarticulate man!” So don’t reproach yourself. It’s all in the Selected Letters and the Life – twenty years ago. Get this. When Syd died Larkin was so cut up he turned to the Church. Quote. “I am being instructed in the technique of religion”! And he describes his sessions with a twinkly old party called Leon.’

‘When was this? How old was he?’

‘Twenty-five. Quote, from Motion. He had always looked up to his father, and they grew steadily closer. To lose him, Larkin thought, would be to lose part of himself.’

‘Christ. Well it was the part of himself he should’ve stomped into the gutter. Couldn’t he see, couldn’t he tell?’

‘The day after the funeral he wrote, I felt very proud of him. Proud. And he started to write a fucking elegy for the old cunt.’

‘Oh, where are they now, the great men of yore? Where the riding whip, where the jackboot?…Well all I can say is, It’s amazing that the poems got out alive.’

The food came, and for the next hour we tried, with only partial success, to recite ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ (eighty lines); we did a little better with ‘An Arundel Tomb’ (forty-two).

‘Something to do with violence / A long way back’. I think what we are seeing here is PL’s unconscious mind (very tardily) beginning at least to register what he could never absorb. People can be violent non-kinetically; and Larkin Senior was an intensely violent man. Sebastian Haffner in 1940 identified the essence of National Socialism: it was a rallying cry for sadists. And Sydney heard that call.

How lastingly extraordinary it is. Larkin’s fastidious soul was shaken by the Patsy visitation: ‘it seemed a glimpse’, he informed Monica, ‘of another, more horrible world.’ That world was bohemia, whose (sloppy but pacifistic) ethos repelled him all his life. As for the ethos of Bavaria and the Brown House and the Beer Hall Putsch – Larkin never seemed to mind that his father was a votary of the most organised and mechanised cult of violence the world has yet known…

‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad, / They may not mean to, but they do.’ Well, whether or not this dad meant to, here is a clear case of Mission Accomplished. As Philip’s sister Kitty said after the cremation, ‘We’re nobody now. He did it all.’

Goodbye to the patriarchs, the little overlords, the goosers and gropers, the disseminators of disquiet, the wife crushers and daughter torturers, the fathers that everyone fears, the enemies of ease, the domestic totalitarians of the mid-twentieth century.

*1 D. H. Lawrence. What if anything does PL mean by this sentence? He means, I suppose, that if Lawrence (‘so good I daren’t really read him’) can be called a fascist, then fascism must have its points. Was Lawrence a fascist? See below.

*2 There is a lone mention of Stalinism. It was forced out of him when that ‘old bore’ Robert Conquest sent him his ‘whacking great book on Stalin’s purges’ (this is an allusion to its size). Conquest’s book was the seminal, consciousness-shifting study, The Great Terror (1968). In his thankyou letter for the free copy, PL managed the following (this is an allusion to the Kremlin leadership): ‘Grim crowd they sound…’ And that was all – ever.

*3 Or not until recently – with the publication in 2018 of Larkin’s Letters Home, edited and introduced at illuminating length by James Booth. Here we learn that Sydney was indeed ‘crudely anti-Semitic’. During the post-war revelations he never ‘acknowledged Nazi barbarism’, turning his guns, rather, on the Nuremberg Trials.

*4 His workplace in City Hall was adorned with Nazi regalia – until the town clerk ordered him to get rid of it. We can just about imagine the scene: Sydney’s bottom-pinching and nipple-twisting against a backdrop of swastikas and lightning bolts.

*5 Christopher’s essay on Letters to Monica had duly appeared in the Atlantic that May…This would be my last trip to the US as a visitor; thereafter I would be a resident. My friend was re-established at the Wyoming, and girding himself for the after-effects of his month in the synchrotron.

*6 Or six, if you’re inclined, as I was for a while, to believe Phoebe Phelps (whose candidate, my mother, would have come between Ruth and Monica). Phoebe can be doubted on optical grounds: if what she said was true, it would be as if Diana Dors had come bustling in on a singletons’ knitting circle in somewhere like Nailsea. Anyway, the Hilly possibility is hereby dismissed.