The Essayist

December 2011

In ‘that sullen hall’ which Owen calls ‘Hell’, the dead soldier from England listens as his ‘strange friend’ – the dead soldier from Germany – explores certain memories and regrets (‘For by my glee might many men have laughed, / And of my weeping something had been left, / Which must die now’), and speaks of war and ‘the pity of war’. Finally ‘that other’ gently confronts the poet with a grievous revelation:

‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried, but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now…’*

Sleep – death’s brother…Wilfred Owen was killed in action soon after dawn on November 4. He was twenty-five, like Keats, and already, like Keats, a poet of Shakespearean pith. His mother Susan – who was Wilfred’s one essential intimate – received the telegram while all the bells of Salisbury were wagging and tumbling in celebration of Armistice Day – November 11, 1918.

At noon on December 15, 2011, as I walked out into the enclosed forecourt of Bush Intercontinental (its low roof dripping with the tepid sweat of cars), Michael Z was as usual waiting for me. He had a book spread flat against the steering wheel, and he started like a guilty thing when I tapped lightly on the glass.

I got aboard and as usual we embraced. Then he straightened up.

‘…This is a dreadful thing to have to tell you, Martin,’ he said. ‘But basically it’s all over.’

Come here about me, you my Myrmidons…I had a sensation of nakedness, including a sensation of cold. That lasted for three or four seconds. Then I managed to lose myself in a finical linguistic question prompted by Salman’s email a day or two ago, addressed to Elena, in which he asked her, ‘Is it true that Christopher has died?’ Not ‘is dead’, I noticed, but the slightly softer ‘has died’. Slightly softer? Actually very much softer; there seems to be an inherent metrical stress on the word dead, imparting something decisive: not a process but a fact…Elena wrote back, saying it wasn’t true, he hadn’t died. But that was a day or two ago.

The car moved through the Houston suburbs (Christopher, now, was sleeping, deeply, and wasn’t expected to reawake) and as we drove the slowly melting igloo I’d been living in – the one with its name, Hope (or Denial), on a little plaque just above the entry tube – turned to slush. Come here about me was a summons: to my myrmidons, my praetorian guard of hormones and chemicals. That was my strategy, it turned out – blind negation, followed by clinical shock.

‘I was up there this morning,’ said Michael. Now we were in the different forecourt, under the shadow of the high-rise. ‘So I won’t…I think I’ll just go home.’

After a moment I said, ‘Yes, go home and be with Nina. How is Nina?’

‘The truth is we’re both very numb.’

Numb was something I understood. It seemed I was almost legless with internal sedatives and painkillers, but I was awake, I was above all alive, and I got out of the car and I walked into MD Anderson.

Christopher was lying on his back with his head at an angle, his face averted, his eyes closed. I went straight to him and kissed his cheek and said in his ear, ‘Hitch, it’s Mart, and I’m at your side.’ His lashes, his eyelids, didn’t flicker…When after a minute I turned, I saw that there were seven others in the room. I registered them one by one: Blue, Blue’s father Edwin, Blue’s cousin Keith, Blue’s daughter Antonia, Christopher’s other children, Alexander and Sophia, and Blue’s very old friend Steve Wasserman. No doctors, no nurses: help from that quarter was at an end. The death-adoring flies, too, had sizzled off elsewhere; their work done, they had moved on elsewhere, they had moved on to another bed in another room.

And so had Christopher – because this wasn’t the familiar wardlet on the eighth floor. His possessions were there, half stowed or half packed, but this wasn’t the billet of an active being, no books or papers, no keyboard on the meal tray, no work in progress. A halfway house, a waiting room.

I quite soon realised what it was we were there to do. So I went round quietly greeting everyone, took a chair, folded my arms, and joined the death watch.

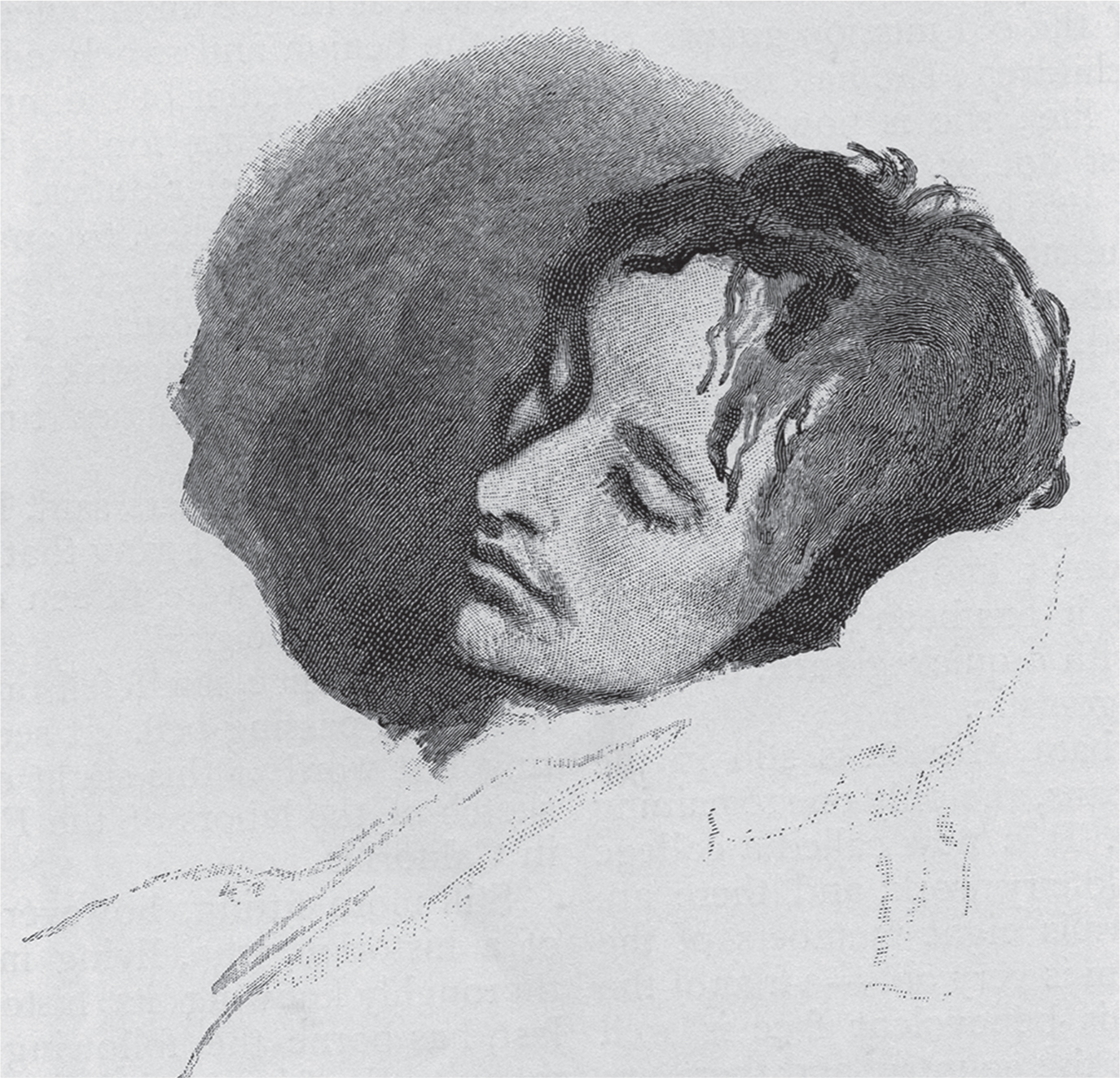

How young and handsome he was. How calmingly young and handsome. He looked like a thinker, a hard thinker, taking a brief rest, his neck bent back – to ease the strain of prolonged and testing meditations…Now reason slept, now the sleep of reason; he looked like Keats on his white bedding in Rome; he looked twenty-five.

From what Michael Z had said (and what Blue had let slip), I was beginning to understand. The disease that Christopher’s death would cure was not the emperor of all maladies, cancer; it was instead ‘the old man’s friend’–that old tramp, pneumonia. Yes, yet another hospital infection (his fourth, his fifth?), and for this particular bout he had waived all remedy.

Entirely typically, it had always been Christopher’s intention ‘to “do” death in the active and not the passive sense, and to be there and look it in the eye’ (‘wishing to be spared nothing that properly belongs to a life span’). Had it worked? Had he, in some sense, already done the dying?

Well, he was insensible now, he was oblivious now. Which, I supposed, was a necessary condition for any death watch. How could it be effected otherwise? You could watch death come, but you couldn’t watch your own death watch. Not even Christopher would contemplate something so terrible…

Indeed, his eyes were closed and his face averted, as if to make doubly sure he wouldn’t see us all gathered there – all those faces that would soon conclusively disappear.

‘[H]e gradually sank into death,’ wrote Joseph Severn, the portraitist, ‘so quiet, that I still thought he slept.’

There he lay…

Two hours had churned by, and we sat in place like art students in class, sizing up a model.

…Not long before I was born my teenage mother used to ‘sit’ at the Ruskin in Oxford. She told me that she passed the hours by ‘pretending to be dead’ – not that she felt at all embarrassed or uncomfortable (she regularly posed nude); no, she relayed the information just to equip me with a trick, or a spell, to make time go fast.

There were muted comments and whispered asides – but nothing that resembled conversation; every now and then one or other of us stealthily and briefly slipped away, to go to the bathroom, to make a phone call, to stretch the legs, to taste some variation in the air…

Around seven I had a smoke with Blue, out in the dusty shrubbery. She struck me as someone quite different from the woman I knew, decidedly reserved or even bashful, but neutrally and unaffectedly so, as if that was her real nature, and all the forthright liveliness I was used to merely belonged to an absent twin.

Days earlier, she told me, Christopher was as usual being prodded and tested and shifted and hoisted, and he said (in a very forceful tone), ‘That’s enough. No more treatment now. Now I want to die.’ He had run out of dry land, and recognised that the time had properly come to make the crossing. These weren’t his last words, not in any formal sense; his last words were a day or two away…

In Houston, even in the winter months, the diurnal temperature seldom drops below sixty-five. Before us, before Blue and me, stretched a fine December evening, and one that looked set to last till midnight…We hurried back up and took our places, as in a gallery or a playhouse, to gaze at a portrait or a motionless mime.

Blue had spoken about Christopher’s coming end dispassionately, almost dismissively. She was getting through it by pretending to be cold.

There was another presence at the death watch, inorganic and at first unregarded, but by now wholly dominant – the point at which all our stares converged.

It was the tall contraption glowering over the far right-hand corner of the bed, and it looked like the innards of an elderly robot, a Bakelite and metal organ tree (stickled together, it seemed, at Crazy Eddie’s discount store): lit-up computer screens, mobile phones, clock radios, pocket calculators, walkie-talkies – each of them heaped one on top of the other, and then studiously titivated, here at MDA, with sacs and vials of nutrients and medicaments. Blood-red, sharp-shouldered digits flashed out their readings.

At eight the blood pressure said 120/80. At nine it said 105/65. It kept on going down.

…Nineteen months ago, when all this began, I used to think, with fearful anticipation, of Auden’s Icarus: ‘the splash, the forsaken cry…Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky’. But now the moment had come I thought of Eliot’s Christ-figure (in ‘Preludes’): ‘I am moved by fancies that are curled / Around these images, and cling: / The notion of some infinitely gentle / Infinitely suffering thing.’

The chest continued to rise and fall, but shallowly now.

The breathing weakened smoothly – visibly but not audibly. No wheezing, no gasping and gulping, no choking: no struggle, no tremor – nothing sudden.

The continuously undulating line at the base of the heart monitor, like a childish representation of a wavy sea, now stretched itself out into a dead calm.

The widow, after a silence, briskly began to assemble her things, and she rose to her feet, saying,

‘Come on. There’s nothing there now. That,’ she whispered to me, meaning the body, ‘there’s nothing in it any more. It’s just – rubbish.’ As we headed into the corridor she turned and saw something among his belongings that for just a moment made her stride falter. With a sharp intake of breath she gasped out,

‘His…shoes!’

Mortality, which appeared in early 2012, lies on my desk in Brooklyn, here in 2018, and I can say with certainty that it is a valiant and noble addition to the literature of dying.

Christopher’s last words were formulaic (though also in my view characterologically superb). But why are Last Words in general so predominantly second-rate? And I mean the last words of our greatest poets, thinkers, scientists, leaders, visionaries, our supermen and our wonderwomen: why can’t the ne plus ultra of articulate humanity, faced with this defining moment, do a little better?

Henry James (1843–1916) came up with ‘So it has come at last, the distinguished thing.’ This is rhetorically very splendid – last words in the high style. He claimed that his valedictory flourish was spontaneous (his ‘first thought’ as his leg gave way and he embarked on a fall). But the high style, by definition, is never spontaneous – and what’s ‘distinguished’ about falling over? I’d say that James had been working on his last words since about 1870.

The best last words known to me belong to Jane Austen (b. 1775), who was dying (of lymphoma) in unalleviable pain at the age of forty-one. Asked what she needed, she said, ‘Nothing but death.’ This sounds impulsive, unbidden, perhaps even serendipitious; it also sounds both weary and resolute, both impatient and stoical. Not content with that, Austen’s crystallised poeticism – even the ‘but’ plays its part – dramatises a fell reality, because ‘nothing’ and ‘death’, here and elsewhere, are synonyms. ‘Nothing but nothing’ was her meaning.

Otherwise, last words are dross, like the defunct human body. And the words that precede death could hardly be as feeble as they are unless something about death rendered them so. Being impenetrable, death defeats the expressive powers, and our best and our brightest can do nothing with it. Well, ne plus ultra – ‘the most perfect or most extreme example’ – derives from the mythological KEEP OUT sign inscribed on the Pillars of Hercules: ‘not further beyond’.

We got back from MDA round about midnight and sat untalkatively in the kitchen and on the patio of the guest house (untalkatively joined by Michael Z). Although my mental state was obscure to me, my body, after its saturnalia of chemicals (now reinforced by Chardonnay), felt familiar: the comedown would soon be followed by the hangover, and a hangover of the spiritual category, strongly featuring remorse and regret. Christopher wrote that regret was for things you did and remorse was for things you didn’t do – sins of commission as against sins of omission…Everyone stayed up, trying to de-coagulate. And around noon the next day most of us went in groups to the airport, and defeatedly boarded flights to San Francisco, Washington DC, New York, and perhaps other cities.

…Christopher’s last words, unlike James’s (and unlike Larkin’s), were unrehearsed. Also inadvertent, because he lost consciousness in mid-thought: his last words – there were only two of them – were simply the words he said last. They were rhetorically primitive, barely more than a slogan or a chant. Yet anyone who knew him is sure to find them full of meaning and affective force. It was Alexander who described the scene to me, over a paper cupful of coffee a few hours before the death; and we both smiled and closed our eyes and nodded.

Yesterday Christopher was lying there alive but unstirring, with his mind in that region between deep sleep and light coma, and he softly articulated something. Alexander (and Steve Wasserman, also in attendance) drew closer and urged him to repeat it. He did so: ‘Capitalism.’ When Alexander asked him if he had anything to add, he said faintly, ‘…Downfall.’ That was the Hitch, comprehensively unconverted – except when it came to socialism, and utopia, and the earthly paradise. Crossing the floor to death: and yet he never changed.

‘Alexander, your father’s not dying at sixty-two. He’s about seventy-five, I’d say – because he never, ever went to sleep.’ We sat there with our paper cups. ‘Christ, it’s so radical of him to die,’ I said. ‘It’s so left wing of him to die.’

…There it lurks before me, under the angle lamp, Mortality – droll, steadfast, and desperately and startlingly short. Usually I pick it up and put it down with the greatest care, to avoid seeing the photo that fills the back cover; but sometimes, as now, I make myself flip it over and I stare. We never talked about death, he and I, we never talked about the probably imminent death of the Hitch. But one glance at this portrait convinces me that he exhaustively discussed it – with himself. Those are the eyes of a man in hourly communion with the distinguished thing; they hold a great concentration of grief and waste, but they are clear, the pupils blue, the whites white. Christopher, long before the fact, mounted his own death watch. Prepared for the Worst was the title of his earliest collection of essays (1988), and it was his lifelong stance and slogan. He felt the compulsion to go looking for the most difficult position, and here he is, in the most difficult position of all – the most difficult position for him, and for everyone else on earth.

On the day D. H. Lawrence stopped living (at the age of forty-four) he said three interesting things. His antepenultimate sentence was ‘Don’t cry’ (addressed to Frieda); his penultimate sentence was ‘Look at him in the bed there!’; his ultimate sentence was ‘I feel better now’ (the last words of many a waning murmurer). Lawrence got the order wrong: he should’ve signed off with Don’t cry…

Don’t cry. They weren’t Christopher’s last words – but they were his legacy, and in the strangest way. He himself was very open to emotion, he was quickly and strongly moved by poetry (literary and political), and he was unalarmed by the sentimental and even the spiritual; but he wouldn’t have anything whatever to do with the supernatural. And so I now say to his ghost,

‘After you died, Hitch, something very surprising happened…It wasn’t supernatural, obviously. Nothing ever is. It only felt supernatural.’

‘How supernatural?’

‘Mildly supernatural. Only a bit supernatural.’

‘And are you suggesting that I brought this about from beyond the grave? Or from beyond the incinerator, because as you know my grave is in the sky.’

‘True – the mass grave of so many of your blood brothers and your blood sisters. No I’m not saying that. It was all your own work – but the work was done when you were alive.’

‘Explain.’

‘I will explain, and I’ll try to make you understand.’

* ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’ has strong claims to being the greatest line of war poetry ever written. And incidentally it could have been ‘I am the enemy you killed, my love’. See ‘Shadwell Stair’, which opens, ‘I am the ghost of Shadwell Stair’, and closes, ‘I walk till the stars of London wane / And dawn creeps up the Shadwell Stair. / But when the crowing sirens blare / I with another ghost am lain.’