5

Regret Reveals Opportunity

My new rule: whenever things go wrong, wait and see what better thing is coming.

SCOTT CAIRNS, Short Trip to the Edge

Early in my career I was a busy executive working to make my mark in the publishing industry. Books were my world, and I loved my work. I was hungry and eager to advance. But work was only part of my life. My wife, Gail, and I started having children a few years after we got married. We had five daughters in less than ten years. As you can imagine, life was crazy.

Given the size of my family, I felt a lot of financial pressure. That, coupled with my natural ambition, was a powerful cocktail. I worked long hours, hoping I could get another promotion and the raise that came with it. For most of those years I also managed extra work on the side to meet our needs and gain financial ground.

Long story short, I often felt overwhelmed with all I had to do. I felt guilty for not spending more time at home, and I was teetering on the edge of burnout. The stakes at work were too high. But the stakes at home were higher still. Somehow I kept it all going, even through a few serious business crises. But eventually I found out that I was in danger of losing my connection with my daughters, and Gail sometimes felt like she was a single mom, widowed by all my work.

Honestly, things were touch-and-go at times. As I became aware of the cost my absorption with work inflicted on my family, it was like a giant regret bomb went off in my lap. Chances are good you can identify to one degree or another.

There’s No Autocorrect for Tattoo Needles

When I was young, the only people with tattoos were bikers, convicts, and sailors. Over the last couple of decades, that’s changed in a big way. Where I live, just outside Nashville, Tennessee, it’s impossible to miss elaborate, colorful designs on full display or peeking out of shirt collars, sleeves, and trousers. And that’s true all over. According to a recent Harris Poll, nearly a third of American adults have a tattoo these days.1 The percentage is higher at home. Three of my daughters have tattoos.

So far my girls love theirs. That’s true for most, but regrets are normal. About one in four laments the decision. Why? Tattoos can last far longer than the desire to get one. Beyond that, not everyone with an ink gun is Michelangelo, and tattoo needles don’t come with autocorrect. Here are a few that miss the mark:

- “Never Forget God isint Finished with me Yet”

- “Everything happends for a reason”

- “Life Is a Gambee So Take the Chance”

- “No Dream Is To Big”

- “Regret Nohing”

According to the Harris Poll, poor execution is one of the main reasons people regret tattoos. A website I checked had well over nine hundred examples of bungled designs, including the ones above.2 No wonder tattoo removal is now the fastest-growing cosmetic procedure in the world.3 And no wonder unflattering tattoos are such well-fitting symbols for regret. But that’s only part of the picture.

When Brené Brown was researching the topic of regrets for her book Rising Strong, a friend sent her a similar example—the parents’-worst-nightmare boyfriend from the Jennifer Aniston movie We’re the Millers, who proudly shows off his “No Ragrets” tattoo. “It’s such a perfect metaphor for what I’ve learned,” Brown said. “If you have no regrets, or you intentionally set out to live without regrets, I think you’re missing the very value of regret.”4

The value? One challenge most of us face in completing the past is the nagging feeling that we failed somehow. This isn’t tattoos. This is existential. If you’re still breathing, you’re probably aware of at least one way you haven’t measured up. After a little “backward thinking” with help from the last chapter, that number can easily balloon to dozens, even hundreds. It can be a downer.

But this is no tragedy. Some people are a little stunned to think regret has any value at all. Our culture tends to miss it. I don’t mean to minimize the pain of regret. The pain can be real and intense. The problem is how quickly we distance ourselves from it. We’d rather not live with the feeling long enough to gain the benefit. That’s a big mistake. When it comes to experiencing your best year ever, we can leverage our regrets to reveal opportunities we would otherwise miss. Look at it the right way, and regret is a gift of God. To quote University of Michigan psychologist Janet Landman in her book on the topic, “It all depends on what you do with it.”5

The Uses of Regret

Before we look at the benefits, let’s examine one common but unhelpful use of regret: self-condemnation. “The delta between I am a screwup and I screwed up may look small,” says Brown, “but in fact it’s huge.”6 When we focus on ourselves instead of our performance, we make it harder to address improving next time around for the simple reason that improvement isn’t the focus.

Let’s say you lost your cool with one of your children or a friend. Or let’s say you flubbed a report that cost your business a lucrative new client. You could go on about how bad you are as a person. That would be small comfort to your friend or coworkers and wouldn’t accomplish anything as far as future behavior. Or you can identify the bad performance. Having done that, you’re in a position not only to repair the present breach but also to prevent it from occurring again.

Worse, self-directed regrets sit on the evidence table in the criminal court of our minds as an ever-expanding mound of exhibits, proving all our worst limiting beliefs about ourselves. Never mind the built-in confirmation bias. We’re all fallible, so if you believe you are a failure, you’ll never run out of proof. Every new instance further cements the story. And since we tend to experience what we expect, as we’ve seen, you’re likely to just get more of the same. If, on the other hand, you believe you fail, you can begin evaluating what’s missing in your performance and seek corrective action. You’re not a failure, so the failure you do experience creates dissonance that requires your attention to resolve. That’s what happened to me when I realized my approach to work was alienating my family. My wife and daughters mattered to me—more than my work—but my actions said otherwise. That dissonance drove me to change my approach and rebuild those relationships.

Landman identifies several benefits of regret. Three are worth mentioning here. First, there’s instruction, which relates back to Stage 3 of the After-Action Review process. Regret is a form of information, and reflecting on our missteps is critical to avoiding those missteps in the future. Next there’s the motivation to change. As Landman says, “Regret may not only tell us that something is wrong, but it can also move us to do something about it.” I sure felt that with Gail and my daughters. Finally, there’s integrity. Regret can work in us like a moral compass, signaling us when we’ve veered off the path.7

These three reasons alone should be enough to rethink our instant dismissal of regret. When the regret bomb blew up in my life, I was able to reevaluate and reorient my priorities. Restoring my most important relationships was hard work, but without regret it would have been impossible. I would have been oblivious to the need or resentful that others weren’t pulling their weight. Regret forced me to own my part in the failure and correct it, and the relationship with my daughters has never been better than it is today. But there’s even more going on here.

The Opportunity Principle

Several years ago a pair of researchers from the University of Illinois ranked people’s biggest regrets in life. Neal J. Roese and Amy Summerville combined the results of multiple studies and subjected them to fresh analysis, along with conducting additional studies of their own. Family, finances, and health all made the list, but the six biggest regrets people expressed were about education, career, romance, parenting, self-improvement, and leisure. Notice how these high-regret areas correlate closely to the ten life domains I outlined at the start of the book. If your LifeScore was low in any particular domain, welcome to the human drama. You’re not alone.

Roese and Summerville mapped a three-stage process of action, outcome, and recall. In the first, we take steps toward a goal. In the second, we experience the result of our effort. If unsuccessful, we often trigger regret. Where it gets interesting is stage 3, recall. The researchers found that “feelings of dissatisfaction and disappointment are strongest where the chances for corrective reaction are clearest.”8 Regrets, in other words, don’t just flow backward like a blocked sewer pipe, oozing bad past experiences. They also point forward to new and hopeful possibilities. They called their finding the Opportunity Principle, and it’s almost 180 degrees from our typical assumptions.

Regrets not only goad us toward corrective behavior, studies show we also tend to feel regret the strongest when the opportunity for improvement is at its greatest. No one does well under a crushing burden of regret. Thankfully, our minds have natural processes like reframing to take the weight off, especially when there’s little chance to fix the situation. We’ve recognized that since forever. It’s where we get folk wisdom like “time heals all wounds.”

What we haven’t always recognized is that regret sometimes dogs our heels precisely because it is signaling a chance to improve our situation, whether that’s going back to college, changing careers, or repairing relationships. Say Roese and Summerville, “Regret persists in precisely those situations in which opportunity for positive action remains high.” This points to at least one reason Landman subtitled her book The Persistence of the Possible. Regret is a powerful indicator of future opportunity.

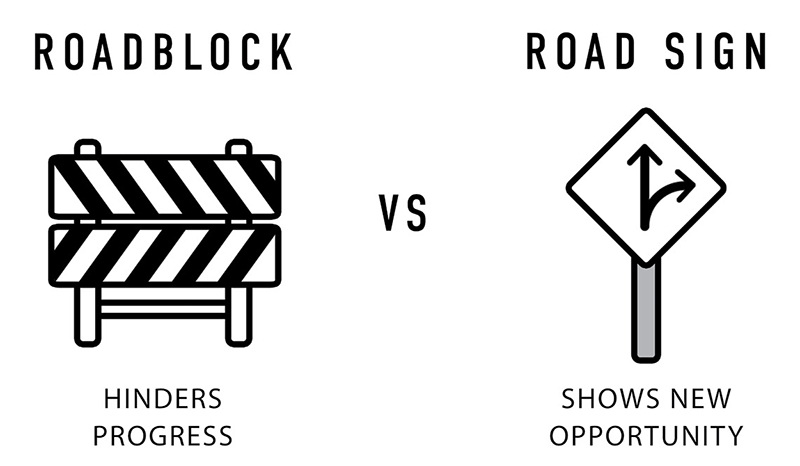

A Road Sign, Not a Roadblock

The Opportunity Principle is a game changer. Think about your LifeScore. (If you haven’t taken the assessment yet, I recommend you do so now at BestYearEver.me/lifescore.) In which domains did you score the lowest? Maybe it’s your social life, avocational interests, and spiritual development. Or maybe it’s your career path or financial health. Whatever those domains are, it’s time to rethink regret. Instead of a roadblock to progress, think of it as a road sign pointing the way forward.

These positive features of regret are baked right into our neurobiology. Brain scans locate the experience of regret above our eyes in the medial orbitofrontal cortex. When that portion of the brain has been damaged, patients not only lack feelings of regret, they are unable to correct behavior that would trigger regret in a healthy person.9 In other words, the fact we feel regret at all is evidence we have what it takes to make positive change in our situations, no matter how dire they might seem. The only people with no hope are those with no regrets.

We can treat regret like a roadblock to our progress—or a road sign that points the way to a better future.

What if your greatest frustrations from the previous year were actually pointing you to some of your biggest wins in the next? What if regret isn’t reminding us of what’s impossible, but rather pointing us toward what is possible? Instead of seeing our regrets as working against the chance to grow and improve, we can see them as actually pointing the way toward that growth and improvement we most desire. Talk about trading a limiting belief for a liberating truth!

As we take the next step in our journey toward your best year ever, I want to encourage you to stay in a frame of possibility. And I have one more suggestion on how to do it.