13

One Journey Is Many Steps

The great doesn’t happen through impulse alone, and is a succession of little things that are brought together.

VINCENT VAN GOGH, from a letter to his brother Theo

At the start of the Civil War, few military careers looked as bright as General George B. McClellan’s. A string of early victories not only earned him the nickname “Napoleon of the American Republic,” they also catapulted him to the attention of leaders in Washington. Lincoln soon promoted him to commander of the Army of the Potomac and, later, first general-in-chief of the Union Army.

The North was excited to have McClellan at the helm. “The troops . . . under McClellan will be invincible,” said the Philadelphia Inquirer at the news of his promotion.1 But the enthusiasm didn’t last. The new commander leapt to training his men but hesitated when it came time to attack the enemy. McClellan was constantly organizing and preparing. According to him, the army was never quite ready. McClellan exercised “obsessive caution,” as his biographer and historian Stephen Sears put it, even when he had the clear advantage over his enemies. All his planning and preparing meant too little action, too late to do any good.

McClellan’s failure to stop General Robert E. Lee at Antietam was the direct fault of his reluctance. “Against an enemy he outnumbered better than two to one, George McClellan devoted himself to not losing rather than winning,” said Sears. “Nor would he dare to renew the battle the next day.”2 McClellan dug in when he should have moved on. At one point, Lincoln famously wrote McClellan, “If you don’t want to use the army, I should like to borrow it for a while.”

Part of McClellan’s problem was that he regularly overestimated the size of the enemy. The more daunting the enemy grew in his mind, the less confidence he showed in the field. Ultimately, he lost Lincoln’s confidence, squandered his opportunity, prolonged the war, and cost the lives of tens of thousands of soldiers on both sides of the conflict. McClellan demonstrates a key truth when it comes to experiencing our best year ever: Setting the goal is only half the job. The other half is taking definitive action.

The Art of the Start

I meet people all the time who get bogged down in planning and preparation. They’d like to launch a new product, find another job, write their first book—but they just can’t seem to pull the trigger. Like McClellan, they feel unsure and unready. So they spend their time dreaming, researching, and planning. Don’t get me wrong. Detailed action plans are terrific—if you’re building a nuclear submarine. For most of the goals you and I will set, however, detailed planning easily becomes a fancy way to procrastinate. It’s a lot easier to plan than take action.

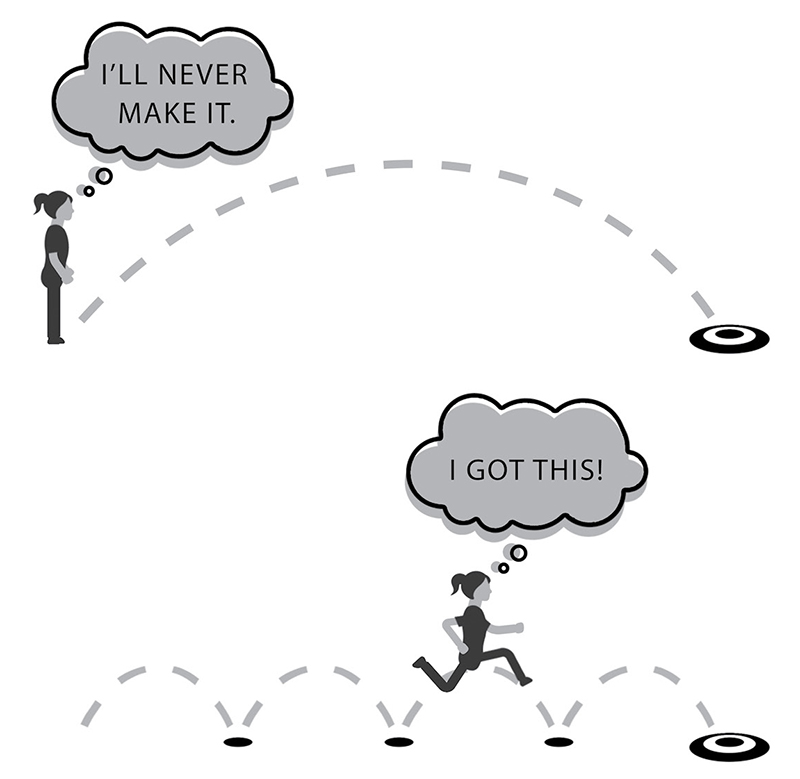

At this stage of the game, the most important aspect of making it happen is practicing the art of the start. You don’t have to see the end from the beginning. In fact, you can’t if your goal is big enough. And the good news is that you don’t need to. All you have to see is the next step. Any goal is manageable one action at a time. But, like McClellan, when we let the task grow and become daunting in our minds, it can leave us feeling indecisive, discouraged, and even paralyzed with panic.

What’s the alternative?

Do the Easiest Task First

Years ago I heard a motivational speaker encourage his audience to “eat that frog.” The line has a long history.3 And it makes sense in its own way: Stop procrastinating and just do the thing you fear. Once you do that, everything else is easy. While that may be helpful in overcoming procrastination, it’s exactly backward for big goals and projects. Instead, you should tackle your easiest task first.

I’ve written several books now, and the way I do it is almost always the same. I start with the easiest task first. I write the title page, the dedication, and the table of contents. Then I think through the chapters, pick the easiest chapter, and tackle it first. A book feels daunting. But one chapter is doable, especially if it’s the easiest one. When I launch a new product, create a new course, or undertake any major goal, I operate the same way.

While we should set goals in the Discomfort Zone, the way to tackle a goal is to start with a task in the Comfort Zone. There are at least three reasons to front-load your task list with easy items, starting with motion. The first step on any project is usually the toughest. But when you start with the easy steps, you lower the threshold for taking action. This is how you trick your brain into starting.

Second, emotion. Getting some quick wins boosts your mood. According to researchers Francesca Gino and Bradley Staats, “Finishing immediate, mundane tasks actually improves your ability to tackle tougher, important things. Your brain releases dopamine when you achieve goals. And since dopamine improves attention, memory, and motivation, even achieving a small goal can result in a positive feedback loop that makes you more motivated to work harder going forward.”4 That’s exactly what happens for me. My excitement level goes up as I work, and it’s the same for my confidence.

Third, momentum. Getting started and feeling good about your progress means it’s easy to build momentum—just like I did with my manuscript. Gino and Staats say checking items off your list frees up mental and emotional energy to focus on other projects. You might also find the tough items get easier as you go. The opposite is also true. When you start with the hardest projects first, you can drain your mental and emotional energy. Now you’re lagging—and still looking at a handful of small jobs on your to-do list. Suddenly the easy looks hard. It’s a momentum killer. You risk getting discouraged and chucking the whole goal out the window. That’s like me walking into the gym, and my trainer says let’s go over to the bench press and press 150 pounds without warming up. That would be stupid. You need to warm up first. That’s what a next step in your Comfort Zone is all about.

Big goals are inherently daunting. If you’re not careful, you can let it discourage you. The solution? Set goals in your Discomfort Zone but break them into a series of smaller steps in your Comfort Zone.

Take the example of fitness. Let’s say you set a goal to run a half marathon this year. That goal is in your Discomfort Zone. You’re not exactly sure how to accomplish it. Maybe you’ve already tried a physical challenge like that and failed. Don’t let the size of the dream be its own demise. Instead of worrying how you’re going to succeed, just commit to an easy next action—like calling a coach.

You’re looking for one discrete task. You basically want to put the bar so low, you can fall over it. Then once that task is done, you can set the next. I don’t care how big the goal is—it can be accomplished if you take it one step at a time. The sample goal templates in the back have space to break down your big goals into next steps.

What if your next step feels uncertain? Don’t sweat it. Just try something and don’t worry if it’s wrong. The goal may be risky, but the next action isn’t. You’re stepping out, but not far. If it doesn’t work out, you just take another step. Stick with the running example. Let’s say you call around and can’t locate a coach. Oh, well. Now try posting on Facebook and seeing if any friends have a recommendation. Maybe there is a local running club you can join and train with. Whatever the situation, try something, and if you get stuck, try something else. Sometimes you have to try several different things before one works.

Seek Outside Help

Sometimes we just can’t land on a next step because we’re not aware of our options or we don’t know what it takes to make the progress we want. The good news is, for almost every goal we want to accomplish, someone else knows how to get there—or at least has a better hunch than you. It may be a friend, an accountability partner, or a professional. You don’t have to start from scratch.

A few years ago I was really struggling with strength training. I’d been running for years, but working with weights can be tough on your own. I’d done strength training in another season of life, but this time I couldn’t make any progress. I just couldn’t gin up enough motivation to get started. “I’m stuck,” I told a friend. “I’ve had this on my goal list for the last couple of years and haven’t made much progress.” He said, “Dude, you need to bring in an outside resource. Call a trainer.” I wanted to slap my forehead because it was so obvious, but I hadn’t thought of it. I should have known better. After all, when I decided to learn photography, I found a course. When I wanted to learn to play the guitar, I hired a guitar teacher. When I decided to learn fly-fishing, I found a guide. There was no difference here. So after the conversation with my friend, I hired a fitness trainer and started working out with him three times a week. Suddenly I got momentum and began experiencing positive results.

Outside resources are almost always helpful in finding the right next step and accelerating your achievement. And outside help can appear in a variety of guises. It doesn’t have to be a professional coach. It could be a book, an article, or a podcast. It could be a friend or somebody at church. Whatever your resources, I bet you can find the help you need to get you off the dime and into motion.

If you’re not sure how to move the needle in your marriage, launch your new business, write your book, restore your relationship with your teenage child, or whatever else you’ve decided to do, I’ve got good news. Someone out there has already been to the mountain. Even if your peak is different than theirs, they can help. There’s a person who knows what to do, even if you don’t. Your next action could be as easy as Googling to find out who.

Commit to Act

Whether you determine your next step yourself or resort to outside help, you next need to schedule it and commit to act. If it doesn’t get on your calendar or task list, it’s probably not going to happen. You’re never going to find time in the leftover hours of the day to accomplish your goals. You have to make time for it. You have to make it a priority and keep it like an appointment, just like you would keep with anyone else.

There’s a huge difference between saying “I’m going to try to make something happen” and “I’m going to make something happen.” The first one is almost like saying, “I’m going to give it a go. If it works, great. But until I see the end result, I’m not going to fully commit.”

The problem is it won’t happen until you fully commit. In fact, researchers have found that when we create backup plans, we can reduce our chances of achieving our original goal. The mere existence of Plan B can undermine Plan A. How? We might divide our energies or settle for second best too soon.5

Scottish mountain climber W. H. Murray put it this way: “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness. Concerning all acts of initiative and creativity, there is one elementary truth . . . that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way.”6

The Other Half of the Job

General McClellan felt certain that his goal was important. “God has placed a great work in my hands,” he said when he took charge of the Army of the Potomac. “My previous life seems to have been unwittingly directed to this great end.”7 But then he stalled out.

Another US general had the same sense of destiny, George S. Patton. He imagined great things for himself as a military commander, starting as a young man. He was born into a military family and excelled at horsemanship and other athletic endeavors, including fencing. Like McClellan, he rocketed to stardom early in his career. He started World War I as a captain and ended as a lieutenant colonel. A pioneer in tank warfare, he was famous for walking in front of his brigade or even riding on top of his tanks into battle to inspire his men. “George will take a unit through hell and high water,” his commander, General George C. Marshall, noted.8

In 1942 Marshall picked Patton to lead Operation Torch, the invasion of Axis-controlled North Africa. Patton faced all the limitations McClellan did. Right after taking the position, Patton found out his troops and supplies were insufficient. Instead of using that as an excuse for inaction, Patton took command and made his undersized army the most effective group of fighters he could manage. And he changed the course of history. “It seems that my whole life has been pointed to this moment,” Patton wrote just before landing in North Africa. “If I do my full duty, the rest will take care of itself.”9

And he did. His strategy: “We shall attack and attack until we are exhausted, and then we shall attack again,” he told his men.10 That determination to act made all the difference. Patton achieved victories in North Africa and then in Sicily. After the Normandy invasion, Patton led his men six hundred miles across Europe, liberating Germany from Nazi control in 1945.

A big goal is only half the equation. If you expect to experience your best year ever, you must take action. And, as we’ll see in the next chapter, you can trigger that action with the right kind of planning.