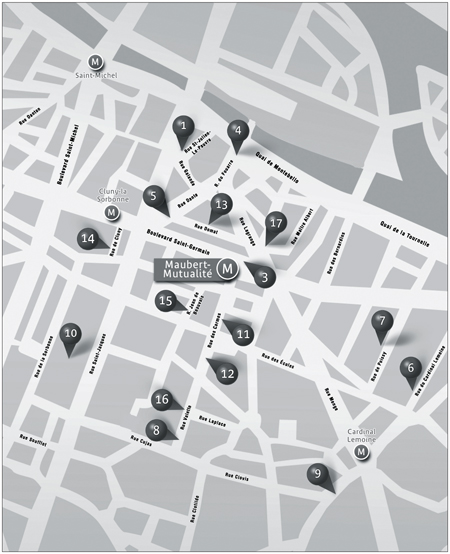

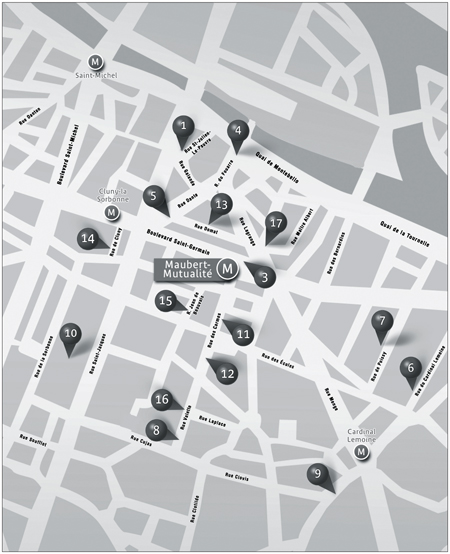

1. At 79 Rue Galande, a small twelfth-century church dedicated to Saint Julian the Poor, an example of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic art. 3. The Place Maubert. 4. The Rue du Fouarre. 5. The Rue Dante. 6. The oldest college (Cardinal Lemoine). 7. And the most beautiful college (Bernardins). 8. At 21 Rue Valette, a vestige of the Collège de Fortet. 9. At 65 Rue Cardinal-Lemoine, a vestige of the Collège des Écossai. 10. The Sorbonne. 11. At 14 Rue des Carmes, a vestige of the Collège des Presles. 12. At 17 Rue des Carmes, the remains of the chapel of the Collège des Lombards. 13. The Collège de Cornouailles is hidden away in an alley that leads from the Rue Galende to number 12a Rue Domat. 14. At 7 Rue de Cluny, a vestige of the thirteenth-century convent of Mathurins, installed in the annex of the Saint-Benoît-le-Bétourné church. 15. At 9a Rue Jean-de-Beauvais, a seventeenth-century chapel surrounded by modern buildings, a remnant of the Collège de Dormans. 16. At 4 Rue Valette, the Collège Saint-Barbe. 17. At 29 Place Maubert, a plaque with Gothic letters shows the water level during a disastrous 1711 flood.

Thirteenth Century

Maubert-Mutualité

The University Takes Off

White letters set against a blue background: the Maubert-Mutualité Métro stop has the classic Parisian subway look. Were it not for the bright orange and very eighties-looking seats.

When you come up out of the subway you can either head toward the Palais de la Mutualité, whose subtle Art Deco façade masks contentious meetings of all kinds, or you can go in the other direction, toward Place Maubert, with its market and its streets teeming with history.

Before all the transformation wrought by Baron Haussmann during the Second Empire, this square was somewhat less grand than it appears today; it was more elongated, enclosed, and hard to access. The modest median strip with the fountain recalls this earlier shape, which was triangular and went north from Rue des Carmes until it hit the Rue Lagrange.

It was in this square that the University of Paris started—right out in the open—for on the Place Maubert, as well as on the Rue du Fouarre, students came to listen to words of the teachers.

Master Albert may have been a Dominican friar but he avoided teaching the lessons required by the Church. He kept his distance in both the literal and figurative sense. He left Notre-Dame to go and teach in the Dominican convent on Rue Saint-Jacques, whose walls he soon found too confining, given the crowds of escholiers, or scholars, who squeezed into them. So he went off to teach in the mud on the Left Bank. Teaching out in the open required both faith and robust health; you were outside in sunshine or rain, or huddled during freezing weather in a simple wooden shack, while eager students sat on the bales of hay. Today students protest for better facilities, and they’re right to do so. At the time, when a bad cold could kill you, their historical comrades ran the risk of picking up nasty illnesses—the flux, for example—simply by following their passion for learning.

Rue du Fouarre, Place Maubert: What is the source of these names?

The word fouarre is from Old French and signifies fourrage, or “fodder.” The reason is that young people with intellectual curiosity would sit here on the bales of hay just off-loaded from the boats that navigated on the Seine.

And why “Maubert”? This is a contraction of Magister Maubus, the Latin name of Albert von Bollstädt, a German Dominican monk who was made a Master of Theology at the University of Paris in 1245. Hence why nearby one can also find Rue Maître-Albert, a dogleg alley that existed in the eleventh century under the name Rue Perdue, or “lost street.” Actually this street was not at all lost; it had been there for a thousand years and cut across all the construction sites and all the urban planning.

Many came to Paris, attracted by the intellectual ferment. A young Florentine man with a thin face, for example, could soon be found sitting on the bales. This was Dante Alighieri, not yet the writer of The Divine Comedy. Hence why a few steps from the spot, the Rue Dante runs today. The poet knew the Rue du Fouarre when it was open-air and frequented by students night and day. Later, in 1358, all that changed. In order to prevent the scholars from coming and going with their drinking and prostitutes, authorities closed off the street by means of two wooden gates as soon as night fell.

* * *

The Place Maubert lay on an important axis of communication—the road connecting Paris, Lyon, and Rome via the Rue Galande and the Rue de la Montagne-Sainte-Geneviève, as well as the road that led to Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle. In the twelfth century, a church dedicated to Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, the patron saint of pilgrims and travelers, was built; small though it is, it remains a handsome example of the transition from Romanesque to Gothic styles. The current façade dates from the seventeenth century, but on the outside you can still see vestiges of the twelfth century, such as on the capitals and columns. On the inside the two bays in the nave are also twelfth century. When Paris as a place of instruction was recognized and restructured, its rector was based here, leaving the streets and squares to the colleges and schools that grew in such profusion on the Left Bank that the whole collection of them was simply called l’Université.

Once deprived of its students, Place Maubert became a dark and fearsome corner of Paris. Old engravings show it bristling with gallows and the “ladders of justice,” with shackles in which blasphemers, bigamists, and perjurers were put on display, bearing the marks of their infamy. The square became a place of hangings and suffering. Moreover, given that the banks of the Seine were not very high and poorly buttressed, the square was often flooded. At number 29 Place Maubert, a plaque with Gothic letters, partly defaced, shows the water level during a disastrous flood in 1711.

* * *

In the twelfth century, knowledge and teaching were still firmly in the hands of the Church. Not just instruction in theology but also in science, grammar, rhetoric, and dialectics took place only within the monasteries. Students had to adhere to the episcopal school, and to submit to strict canon law as laid down by the authorities at Notre-Dame on Île de la Cité. Faced with such rigidly prescriptive interdictions, dissidents inevitably emerged. These were not dangerous rebels, nor even rogue humanists; they were simply clerics who dreamed of a little independence. To maintain some autonomy from the pope and the episcopal school—which alone was permitted to issue diplomas—they set up shop on the Left Bank, where the communities of masters and students gained greater stature by literally moving up the slopes of Mount Sainte-Geneviève.

All this was done in some confusion, with each master assuming that he could teach and each pupil believing that he could choose his professor. The bishop of Paris protested vehemently against these infringements on his authority.

In 1200, Philippe Auguste decided that he needed to restore some order. He regularized the relative freedom of the schools and conferred upon them letters of patent. Henceforth they would be collectively called Universitas parisiensis magistrorum et scholarum. Again the word universitas was being defined in its strictly Latin sense, which means “society,” or “company.” The term designated a collection of people engaged in the same activity. In any case, the king created a frame in which teaching could take place independent of the ecclesiastical yoke. The thirteenth century would be the century of the university.

The most illustrious teachers opened their courses on Mount Sainte-Geneviève and the students followed them in droves. These teachers sought to distance themselves from orthodoxy, meaning from juste opinion, or right-minded thinking, as imposed by the Church. They wanted to teach such things as medicine, a difficult task given that Pope Honorius III forbade instruction in it to the monks in 1219, fearing that instruction in such scientific nonsense would distract these servants of God from true scholarship. The works of Hippocrates and Galen were therefore studied more or less clandestinely—or in any case at the margins of the Church—and taught by independent-minded professors of various religious orders.

* * *

Soon enough, the Left Bank was teeming with colleges and schools that attracted not only students from the realm but from across Europe.

In his book Western History, Bishop Jacques de Vitry gives us a somewhat frightening picture of the Latin Quarter that was taking shape. He was of course a loyal cleric, and therefore horrified by what was happening there, as much on the intellectual plane as on the personal. Still, his account offers a view of medieval Paris.

For Jacques de Vitry, the city was “a scruffy goat” and the good bishop was shocked to find that prostitutes were everywhere. He described houses on the Left Bank in which there might be a school on the first floor and a bordello on the ground floor. Students could therefore pass seamlessly from the joys of learning to those of the flesh. And in this little world were gathered Frenchmen, Normans, Bretons, Burgundians, Germans, as well as Flemish, Sicilian, and Romans, all fighting each other under the smallest pretext, while the teachers, who seemed more preoccupied with coins than with pure science, tried to break up the fights. And in the meanwhile they were all engaging in useless and vain arguments, which, in the eyes of the good bishop, were simply wrongheaded, and based on considerations other than those of the well-being of the mortal soul and the inevitability of divine omnipotence.

To Jacques de Vitry’s great displeasure, schools were proliferating on the Left Bank. Wealthy aristocrats, as well as a number of religious orders such as the Dominicans and the Franciscans, were financing operations in which students were fed and lodged and given instruction. Between Place Maubert and Mount Sainte-Geneviève, colleges were sprouting up everywhere. Some served only a small handful of students, and there were so many that they were constantly joining operations or getting swallowed up by one another. Hence for example the Collège des Irlandais—the college of the Irish—took over the Collège des Lombards, and the Collège du Danemark was sold to the Carmelite convent; the Collège de Presles became part of the Collège de Dormans-Beauvais, and the famous Collège de Coqueret was eclipsed by the Collège Sainte-Barbe. Forty-two thousand students, between the ages of fifteen and fifty, followed courses in some seventy-five institutions of higher learning. In the other European capitals schools were rare and few. Paris had unquestionably become the intellectual center of the world.

* * *

In 1229, six years after the death of Philippe Auguste and three years after the death of Louis VIII, and while France was living under the regency of Blanche de Castille—who was to remain regent until Louis IX reached his majority—the university rebelled. The students had a terrible reputation by this point; these young people, who were supposed to represent the country’s elite, so frightened the bourgeoisie of Paris that at night the streets were deserted. Sometimes with reason, the students were accused of stealing to survive, of kidnapping women from across town and having their way with them, and even, occasionally, of murder. To impose order, Guillaume de Seignelay, the bishop of Paris, threatened to excommunicate anyone who walked around armed. The students sneered at this threat and carried on as before. The bishop became angry and ordered the arrest of the more violent among them and banished others. Let them go hang themselves elsewhere, ran his thinking.

Where have all the colleges gone?

One of the oldest schools carried the name of its founder, Cardinal Lemoine. This college was to have been completely razed at the end of the seventeenth century, or so the history books tell us. Here again my insatiable appetite for going after lost stones came to the fore. Historians of Paris such as Jacques Hillairet quite often mention Le Paradis Latin, a large amusement hall constructed on the remains of the college and which features a mysterious private passageway that is not open to the public. However, if you barge your way into Le Paradis Latin, you will find an entire section of an old structure and large blocks of stones that without question predate the seventeenth century: this is a part of the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine. If you bend down to these stones, near the former entrance toward the stairs, you can just make out grooves that were cut out by the hands of the escholiers: “3C.” This indicates that a student lived on stairway 3C.

The most beautiful of all the colleges still visible today is that of the Bernardines, founded in 1224. Enlarged in the fourteenth century, it offers impressive testimony to the secular medieval architecture of Paris, with its Gothic windows and stonework. At number 24 Rue de Poissy, the vaults in the basement—an ancient cellar—can still be seen and the ground floor as well, where the convent’s refectory was located. The last entirely original structure still standing contains the largest Gothic room in all of Paris—more than 115 feet in length. After five years of restoration, this immense space dedicated to research and study is now open to the public.

At 14 Rue des Carmes, you can find the remains of the College de Presles, founded in 1314. Behind the long ornamented windows, people still live in what once was a sixteenth-century chapel.

At number 17 on this street are the remains of the chapel of the Collège des Lombards, founded in 1334. The main entry dates from 1760 and the other parts of the chapel look somewhat strange, having being washed and eroded by the waters of a fountain that used to be there

The Collège de Cornouailles, founded in 1321, is hidden away in a small alley that leads from the Rue Galende to number 12a Rue Domat. After you reach the first inner courtyard, turn around and you will see before you the entry building of the school, nearly seven centuries old.

The Collège des Écossais—the Scottish School—was located at 65 Rue du Cardinal-Lemoine. Transformed into a prison during the Revolution, it was made into an Anglican church in 1806. There one can find a stairway and a cour d’honneur, or main courtyard. The façade bears the inscription COLLÈGE D’ÉCOSSE, and an escutcheon with “FCE,” which means “Fief du Collège d’Écosse,” a sure sign that you are in the heart of a university that wanted to be truly international.

At 9a Rue Jean-de-Beauvais is a chapel dating from the seventeenth century. Entirely surrounded by modern buildings today, it is a remnant of the Collège de Dormans, created in 1365.

At 21 Rue Valette you will find a stairway, yet another vestige. It leads us into the courtyard of the former Collège de Fortet, founded in 1394. Here is a silent and luminous window into history, a place open to the skies and yet right in the heart of Paris. The sight of the stars spreading endlessly out before you may make you want to escape the world. That’s exactly what the student John Calvin did when he was being hounded for heresy. The school’s most famous student took to the roofs and made his way to Geneva, where he advanced his reforming theory. There is a lovely historic irony to this, for the college was the birthplace of the Counter-Reformation movement: here the Catholic Holy League of the Duc de Guise was created in 1572. As we will see the duke was the instigator of a terrible massacre of Protestants.

Arrayed against such radicalism, the Collège Saint-Barbe, known for its open-minded spirit, taught a discipline that today has mostly been neglected: logic. This college can be found on the Rue Vallette, and absorbed what was formerly the Collège de Coqueret, famous for having educated the Renaissance poets Joachim du Bellay and Pierre de Ronsard.

In February of 1229, after the carnival on Lundi Gras—Fat Monday—a group of students went to drink at an establishment in the neighborhood of Saint-Marcel. At the end of the evening, suitably tipsy, they got caught up in a lively discussion about the cost of the wine they had drunk; it cost more than they had in their purses. Soon enough words got heated and blows followed. The café owner yelled so loudly that a few stalwart locals from the neighborhood ran to help. The fight between the students and the Parisians went all night, until finally the naughty students were somewhat rudely expelled from the premises.

The next day, humiliated by this defeat, the students came back and surrounded the tavern. Armed with heavy wooden bars, they started to wreck the place and then went from street to street, damaging other shops. Along the way they attacked whomever they happened to come across, wounding and killing at random in their rage.

Outrage spread across Paris, and came to the attention of the regent herself. She declared her support of the citizens against the students and ordered law enforcers to “punish the students of the University.”

It is very hard to tell one student from another and the gendarmes didn’t make much of an effort to distinguish between them. They simply mounted the ramparts and went after any student they happened to come across, killing several, wounding others, and robbing everyone.

Now it was the university’s turn to feel itself wronged—its privileges trampled upon, its independence contested, and its students under threat. No one seemed to know what to do. To exert pressure on the authorities, masters and students made use of a new method: they went on strike. As soon as the teaching came to a stop, the schools cleared out. The word grève—“strike”—would not appear for another six centuries, but all the elements of uncompromising conflict were in place. Students and teachers left Paris to go teach or study elsewhere. The towns of Angers, Orléans, Toulouse, and Poitiers were only too happy to reap to their profit the splendid reputation of the Parisian university. Even England’s king, Henry III, welcomed several who were out of favor in the French capital to Oxford.

Neither side would budge. The differences seemed unresolvable. The university fought for its privileges and its independence. The royal authority wanted to establish its right to maintain order. Months went by. The university remained an empty shell.

“One must know when to end a strike,” Maurice Thorez, the French Communist leader, would say one day. The problem was no different in the Middle Ages. Happily, Pope Gregory IX found a way to end the stalemate. He wanted Paris to remain a place of higher learning, and particularly religious training. He pushed hard for negotiation, and finally insisted that it take place. For his part, young Louis IX, all of sixteen, sided with his mother.

Finally, however, Blanche de Castille softened her stance and agreed to compensate the students who had been the victims of the gendarmes, restoring to the university its rights and privileges; she also persuaded the city’s landlords to offer affordable housing for the students. For their part, the bishop of Paris and the abbots of Sainte-Geneviève and Saint-Germain-des-Prés, along with the canons of Saint-Marcel, spoke in their sermons about the need to respect the teachers and students. This struggle between public authority and academic autonomy endures to our own day.

Pope Gregory IX agreed to recognize the diplomas obtained by the students who had taken refuge in Angers and Orléans, on the condition that they return immediately to Paris. Moreover, the Holy Father confirmed that the students had the right to make their own statutes, and were even authorized the right to use “stoppage”—meaning a strike—in the event that a student was killed and his killer went unpunished. Better still, in the papal bull entitled Parens scientiarum universitas, dated April 13, 1231, the pontiff recognized in perpetuity the jurisdictional and intellectual independence of the University of Paris.

The students and their masters returned to Paris. Two years had passed since the strike began. Courses started up again and the city’s inhabitants were happy to see the Latin Quarter once again hopping with activity.

* * *

Under the reign of Louis IX, better known as Saint Louis, the university expanded yet further. Its seat would depart from Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, which had become too constraining, and move to the Sorbonne, where it remains to this day. This Sorbonne, on which by now all the faculties of greater Paris depended, started as simply one of the neighborhood’s colleges, founded in 1257 by the king’s confessor, Robert de Sorbon.

What remains of the Sorbonne of yesteryear?

The Sorbonne’s renown spread quickly across all of Europe. Nonetheless, in the fifteenth century, the Sorbonne fell back into the hands of the Church, which finally had recognized the university, principally to gain control of it. With the birth of humanism, new dissident colleges were founded. The Sorbonne lost its influence, becoming as opposed to the new ideas as the old Notre-Dame school had once been.

One event that marked both the extent of its fame and the beginning of its decline was the creation in 1470 of the first printing press in France, which was put within its walls. The Sorbonne was effectively turned into an arm of royal and papal power.

In the seventeenth century, Cardinal Richelieu, though loyal to the pope, tried to rescue the Sorbonne by means of his own private funds. He invested large sums to burnish the old school’s coat of arms. The buildings that can still be seen today date not from its beginnings but from Richelieu’s efforts (as well as others in the nineteenth century). Inside the chapel one can admire Richelieu’s tomb, sculpted by Girardon. Around the chapel whose dome Richelieu had had constructed, with its archetypically neoclassical cupola and its three levels, one finds only modern buildings. Nothing remains of the medieval structures. On the uneven pavement of the main courtyard are white dots that indicate the placement of the first buildings. The rest of the original Sorbonne was buried. Large neo-Renaissance chimneys, intended to recall the medieval originals, were built in the nineteenth century. At the time, “restoration” did not mean the same thing as “reconstruction.”

The Sorbonne become so dominant because its founder was a true pedagogue. Other teachers opened colleges to house poor students, mainly with the goal of recruiting some among them to become priests and clerics, or at least to make them indebted to the order or to those who had taken them in. Robert de Sorbon, on the other hand, was not interesting in training servants. He was determined to inculcate in his pupils a sense of discipline, a sense of how to study, and a taste for demanding intellectual challenges.

At the moment when the other colleges were at war over theological and philosophical matters, the Sorbonnards were being armed with arguments and facts. Even today, when you say “Sorbonne” you mean “university.” That is how one college among all the others, but not like all the others, eclipsed its rivals.

Saint Louis had no choice but to guarantee the independence of the university. He had acquired for quite a large sum a piece of the true cross from Baudouin II, the emperor of Constantinople, who was in bad need of money, as well as the sacred vinegar-soaked sponge that His Roman executioners had given to Christ and the lance that had pierced His side. Along with the crown of thorns, Moses’ staff, the blood of Christ, and milk from the Virgin, the collection of relics in the king’s possession was truly impressive. The little Saint-Nicolas chapel in the Cité palace seemed insufficient for housing it. Something better, bigger, more beautiful, and more opulent was called for.

Pierre de Montreuil, the architect to undertake this, transformed the modest chapel into a masterpiece of the Gothic style. It was solemnly consecrated on April 26, 1248, two months before Saint Louis left for the Crusades. Today, these relics, which were dispersed or destroyed during the Revolution, are to be found in the vaults of Notre-Dame. The chapel, now called Sainte-Chapelle, remains nearly intact, even if now oddly surrounded by the Palais de Justice.

For five years, Louis IX battled it out under the citadel of Cairo, and reestablished the walls of Cesare and Jaffa, and then finally returned to his realm when he learned of the death of his mother, the former regent, Blanche de Castille.

On his return, the king became concerned about how the city was run. Paris now boasted one hundred sixty thousand inhabitants and there were recurring problems of safety. Citizens were being robbed and murdered with disconcerting ease. The municipal authorities were weakened, because the city’s statutes were a little vague. Unlike other cities in the kingdom, Paris had no bailiff, as the sovereign did not want to be represented in his own capital. People worried about what would happen when His Highness went off to do battle at the ends of the earth.

Saint Louis urged the bourgeoisie to organize themselves and asked the merchants to choose from among them a “provost” who would assume governance of the city’s business. Exercising his authority from the parloir aux bourgeois, a sort of city court, the provost took charge of commercial activity and river traffic.

Moreover, the king named a provost of Paris who would be installed in the Grand Châtelet fortress, from whence he would dispense justice, establish taxes, direct the royal gendarmes, and guarantee the university’s privileges. Starting in 1261, Étienne Boileau assumed this important position. A talented organizer, this just and honorable man succeeded in bringing peace to the streets of Paris.

In 1270, Louis left on his second crusade with peace of mind. He had given his city the organization that it still bears to this day. The provost of merchants is the mayor; the provost of Paris is the chief of police.