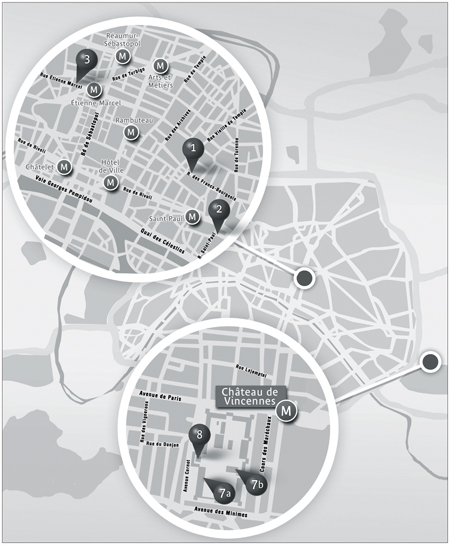

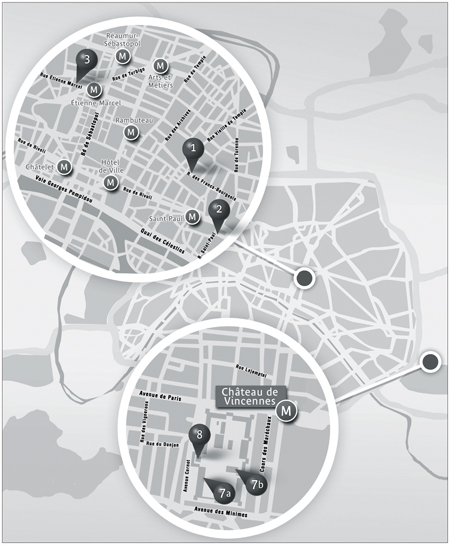

1. 38 Rue des Francs-Bourgeois, where the Duke of Orléans was murdered. 2. On Rue Saint-Paul, the Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis Church, whose clock dates from 1627. 3. At 20 Rue Étienne-Marcel, the tower that Jean the Fearless built to protect his residence. 7a-7b. Château de Vincennes. 8. The Château de Vincennes keep.

Fifteenth Century

Château de Vincennes

Paris at Risk

Now we shall permit ourselves to take a new little excursion outside Paris to have a look at the luminous stones of the Château de Vincennes, a place that as we will see is dominated by its dungeon keep, the home and safe house of kings.

Traumatized by the assassination—in his presence—of his two marshals by Étienne Marcel, King Charles V refused to spend any more time in the Cité palace, where this terrible event had taken place. Instead he focused on finding a place where his power would be safe and with that in mind started building Saint-Pol, located on what is today the Quai des Célestins. This vast assembly of buildings surrounded by beautiful parks—which no longer exist today—afforded greater security than anything within the confines of Paris. Charles V also turned his gaze to the Louvre and had his library, constructed of precious woods, installed in one of the towers; his collection of books was the foundation of what would eventually become the Bibliothèque Nationale.

Lastly, he built the château at Vincennes. The dungeon keep and its wall were completed in 1371; in 1380, he finished the surrounding wall. When he began these construction works, Charles V wanted not to construct yet more new utility buildings, which already existed, but to increase his living space. The design of Vincennes revealed the royal will to change the very nature of construction, and to do more than build still another fortress at the gates to Paris.

This architectural ensemble, which is remarkably well preserved, bears exceptional historical interest. More than anything—more than written texts and archival accounts—it evokes in its very stones the birth of the modern state. In effect Charles V’s project was not only to distance himself from Paris, which seemed to be turning into a trap for royal power, but to adopt a new way for authority to function. The king’s entourage—advisers, officers, scribes, and secretaries—were assuming a growing importance and starting to form a close and effective team. This new form of “governance” marked a turning point for the monarchy, one which presaged the modern state.

Moreover, there was a need for centralized power: the fifteenth century promised to represent an inexorable plunge into the depths of war, famine, and death. The people trembled because the kings and princes had redesigned the landscape to extend their privileges and holdings. Even religion, the ultimate recourse for a downtrodden population, offered few givens: the Great Schism that divided the West meant that there were two pontiffs on the throne of Saint Peter—one in Rome and the other in Avignon. The disunity of the soldiers of Christ encouraged the conquering ambitions of Islam; the sultan of Turkey hid no longer his eagerness to take Constantinople, the dying flame of the Byzantine Empire. In Europe, King Henry IV of England was facing revolts from the Scots and the Irish, but these did not keep him from continuing to lay claim to Brittany, Normandy, and Flanders.

In France, Charles VI, who ascended to the throne in 1380, seemed to have lost his wits. Staring into space, he wandered around the corridors of his palace at Saint-Pol, poking at the flesh of his thighs with a little iron lancet and crawling on the floor to lap at his bowl like a dog. Then the lunacy seemed to dissipate and the king once again took hold of his mind and the reins of government—at least until the next attack. Successive regents, responsible for the proper functioning of the state during the king’s “absences,” took advantage of them to pillage the royal treasury. Charles V’s achievements, political and geographical, started to melt away like snow in sunshine. Paris was in misery and during the winter nights wolves made their way into the city to devour whatever poor souls they found dragging around the deserted streets.

* * *

On November 23, 1407, the war without end with England took a new turn. That evening, Louis, the Duc d’Orléans, the brother of King Charles VI, dined at the Barbette residence with his sister-in-law, Queen Isabeau of Bavaria. The latter had not long before given birth to a weak baby boy who had not lasted more than a few days. Louis had many reasons to find himself at Isabeau’s side. It was quite possible that he was the father of the child, whose rapid and silent disappearance was perhaps a good thing, given that it put an end to speculation.

But what if the child had not died, after all? And what if it hadn’t been a boy but a girl named Jeanne? Joan of Arc as the fruit of the love between the queen and the brother of the king—this is a seductive and persuasive thesis promoted by a number of historians.

Far from Saint-Pol, where Charles VI was locked up during one of his episodes, the queen had built this private residence at Barbette, a small and discreet little jewel located on Rue Vieille-du-Temple—of which, alas, nothing remains. And it is there that Isabeau, a woman of thirty-six, tried to reignite the dying embers of her ardor. She was still beautiful, with her long, fine face and graceful body, which hardly carried the marks of the eleven children that she had already borne the king. The queen threw herself into a passionate affair with Louis, the “handsome stud ready to whinny before all the ladies,” as the rumor had it.

These two loved each other with a passion in which the sweet thrill of the forbidden mixed with political ambition. In effect, understandings, allusions, and diplomatic interests were never absent from their embraces. Each needed the other, or believed that they did.

The king’s mental condition had made Isabeau the realm’s regent. She presided over the Royal Council without also being able to lead it. Jean the Fearless, the Duke of Burgundy, was seeking to extend his influence, but he was thwarted by Louis d’Orléans. Beyond this struggle between individuals, there was still the war with England, which was at the heart of the central debate: should the truce be renewed, as the Duke of Burgundy wanted, or should the fight against the English continue, as the Duke of Orléans believed?

At Barbette, the evening turned out to be a pleasant one, and in the laughter and carefree atmosphere the death of the child was for the moment forgotten. Then, suddenly, one of the king’s valets presented himself to the duke.

“Monseigneur, the king commands that you come to him without delay. He is anxious to speak with you about a matter that concerns you both greatly.”

By this point Louis was used to his brother’s whims, and to being summoned in the middle of the night to share some delusion with him. Deluded or not, however, the king was still the king. He took his leave of Isabeau.

In the Parisian night, perched on his mule which advanced with small steps, Louis sang gaily along while five or six porters carrying torches lit the way through the dark streets. While Louis was passing by a tavern with a sign that bore the image of Notre-Dame, twenty or so men came hurtling at him.

“What is this? I am the Duke of Orléans!” he protested, believing that he had fallen into the clutches of thieves.

He was not given the time to speak another word. He was toppled from his mount and fell to his knees. Trying to rise he was struck and killed with blows from hatchets, swords, and clubs.

“Murder! Murder!” a cobbler’s wife screamed out. She had heard the fracas in the streets and from her window tried to alert people.

“Silence, evil woman!” one of the assailants shouted at her.

Where was the Duke of Orléans murdered?

While nothing remains of the Barbette, as I said, the small street that once led to its back entrance is still there. It is in the dead-end street of Des Arbalétriers, at about number 38 Rue des Francs-Bourgeois, that the crime was committed.

With news of the assassination, the Sire of Tignonville, Paris’s provost, had the gates to the city closed and ordered his archers to restore order to the streets. It was feared that the victim’s allies would seek their revenge.

Two days later, a spectacular procession went from the Blancs-Manteaux Church, where the body of the prince lay in state, to the Célestins Church, where he was to be buried. The king of Sicily, the Duc de Berry, the Duke of Bourbon, and the Duke of Burgundy himself—in short, the greatest figures of the realm—carried the coffin, which was covered with blue velvet embossed with the fleur-de-lys.

The provost’s investigation tended first toward suspicion that this was a matter of a jealous husband—in other words, the king—but the truth soon became clear. Jean the Fearless, the Duke of Burgundy, had ordered the crime.

Evidence of his guilt made plain, Jean gave up his show of grief and pronounced his pride at having accomplished this act of homicide. He had done it, he maintained, for the good of the realm and the greater glory of France. Who could mourn a man who simply emptied the royal treasury to build himself castles and pay for his numerous mistresses?

The situation soon became untenable. On the one side was Jean the Fearless, who benefited from the support of Parisians because of his promises to lower taxes and control the excesses of the monarchy. On the other was Charles d’Orléans, son of the murdered duke, who clamored for revenge and enjoyed the support of the other noble lords. At thirteen, however, he was a boy rather than a warrior. The next year he was married off to Bonne, the daughter of Count Bernard d’Armagnac, and in his new father-in-law he found his champion. Henceforth the Burgundians and the Armagnacs engaged in a war that would tear the country apart.

* * *

Conscious of what would be involved in the fight to take Paris, Jean the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, decided to transform his private residence on the Rue Mauconseil into a fortress. The setting of the building was ideal for this, for it abutted two solid stretches of the wall that Philippe Auguste had built, a rampart that had been surpassed once the city had outgrown its thirteenth-century limits; twenty-five years earlier, these older walls had been replaced by an even larger wall. The dilapidated fortifications did more than reinforce the duke’s residence. Its abandoned towers had become refuges for the homeless, and in the moats emptied of their waters huddled bands of roving mendicants. Meanwhile the round paths were transformed into promenades where the Parisians played at boules.

What remains of the Duke of Burgundy’s fortress home?

In the sixteenth century, the duke’s home was completely reconfigured, and became an auditorium where one was initiated into the mysteries of the religious vocation. In 1634, under Louis XIII, a royal troupe took residence there. It was here that the main works of Pierre Corneille were created, then nearly all of the tragedies of Jean Racine.

In fact it was in this theater Racine discovered Champmeslé, the young actress who played the role of Hermione in his Andromaque. The young woman displayed such tempestuous passion and overwhelming emotion that after the performance the playwright ran backstage, his eyes burning, and fell at her feet, thanking her for giving him such intense happiness. From that point on, Racine never left Champmeslé, and swore to her his undying love. This lasted for a good six years. The Marquise de Sévigné wrote, “When La Champmeslé entered the stage, a wave of admiration swept from one end of the theater to the other, and the entire hall was under her spell, for her to bring to tears whenever she felt like it.”

The building remained a theater until 1783, the year in which the actors invested in the new Comic Opera that had just been built. The old theater became a leather market and then was completely demolished in 1858, to allow Rue Étienne-Marcel to break through.

It was at number 20 Rue Étienne-Marcel where the tower that Jean the Fearless built to protect his residence stood. Here in the middle of Paris is a surprising example of Burgundo-Medieval architecture—and one you can visit. Inside one can find a guardroom on the street level, some apartments on the first floor, a handsome room on the second, the sleeping room of the horsemen on the third, and the wonderful room of the duke himself on the fourth.

From the top of the first spiral staircase are two fascinating reminders of the Duke of Burgundy. First there is the magnificent oak etched into the vaults. The oak has three types of leaves: those to recall the father of Jean the Fearless; those of the hawthorn in memory of his mother; and the leaves of the hops for himself (a leaf from the north, as his mother had been Flemish). Second are two windows, the first bearing the coat of arms of the duke and the second showing a carpenter’s plane. This was the response to the danger posed by Louis d’Orléans, who wanted to beat him with a club and was as a result “leveled” by Jean; he was laying claim to his crime.

To complete the defense of his house, Jean the Fearless had a solid tower constructed, one that rose proudly nearly ninety feet, and seemed to thumb its nose at the Louvre and the royal residence at Saint-Pol, the two seats of royal authority. Behind the high walls of his fortress, the duke had nothing to fear of the inconstancy of the king or the power of the mob.

While Jean the Fearless was having his tower constructed, the Count of Armagnac was raising an army of mercenaries in the south. These were tough working men who dreamed only of pillaging whatever regions they crossed. They came to Île-de-France and ravaged the farms and the fields, then moved progressively all the way to the moats that protected the suburb town of Saint-Marcel on the Left Bank. They entered Paris but on November 2, 1410, a treaty was signed that immediately arrested their military operations. According to the terms of this treaty, each prince must return to his own lands and not return to the capital except with the consent of King Charles VI.

The winter passed in relative calm. As soon as spring came, the war between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians was picked up in Beauvais and Picardy. But Paris was always the true prize. In the month of August, the Parliament—the city’s judicial court—sought to maintain the peace and to accomplish this called for the arrest of anyone found making speeches deemed dangerous to public safety. To make sure this new order was followed to the letter, the men of the Parliament nominated a governor of Paris, and the man chosen was Valéran de Luxembourg, the Count of Saint-Pol. The count was a loyal vassal of the king, like everyone, but had also formed an alliance with the Burgundians.

The count and his ally Jean the Fearless went after the Armagnacs. They created a militia consisting of butchers, slaughterers, peltmakers, and surgeons; in short, men who were handy with knives and used to the sight of blood. This fierce brigade, which took on the noble-sounding title of “royal militia,” had as their mission to arrest anyone in Paris known to be on favorable terms with the Armagnacs.

This inaugurated a season of bloody and blind vengeance. If someone wanted to get rid of a neighbor or a rival, all he had to do was call them an Armagnac. The militiamen would toss the guilty party into a ditch and then pillage his house; most often these supposed Armagnacs were simply drowned in the river. Even the king and his family were not entirely free from suspicion. They left Saint-Pol and moved into the Louvre, which their troops could more easily defend in case this band of butchers turned against the throne itself.

These practices pushed the most prominent Parisians, led by the provost of the merchants himself, to leave town, both to save their necks and so as not to be forced to bear silent witness to these horrors.

No one seemed capable of ending the chaos. A higher power was called for. Thus the canons of Sainte-Chapelle, the Benedictine monks, the Carmelite brothers, and the Mathurin monks gathered together their spiritual forces and processed in bare feet to Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois, followed in reverent silence by the counselors of the Parliament. It was not a matter of choosing between the Armagnacs and the Burgundians; they simply wanted to create universal accord by universal devotion. Through their prayers, chants, and hymns they asked for princes to make peace among themselves.

The procession, however, convinced no one. In any case, in the month of November 1411, Jean the Fearless entered Paris at the head of English troops. Three thousand Parisians rushed to his side. Henceforth, Paris and its surrounding villages belonged to the Burgundians; the Armagnacs were run out of the kingdom and their goods were confiscated. For its part, Parliament, which was suspected of leaning toward the Armagnacs, was fined a thousand livres, which would be used to pay the English troops for their help and getting them, temporarily at least, to remove themselves. Henry V, the king of England, sought to profit from the civil war in France and take back some of the lands that had been lost.

At the end of April 1413, the popular classes had seen their city and indeed the entire realm suffer enough. They rose up under the leadership of a swindler named Caboche. Caboche’s real name was Simon Lecoustellier, but given that his profession was smashing the skulls of cows in order to extract the brain (effectively putting the kibosh on these creatures) he was named Caboche—“head”—and those who followed him were “Cabochiens.”

Jean the Fearless thought supporting this rebellion might be a good strategy and lent his support to the Cabochiens, hoping that after they had done the dirty work he could claim the spoils. In the merry month of May, the Cabochiens turned Paris into a horrific scene of violence. They stormed the Bastille and killed the prisoners held within. Anyone who seemed as if he might be allied to the Armagnacs was murdered. The provost of Paris was beheaded. A new law consisting of 258 articles was imposed upon the Parliament to institute strict controls on public expenditure, a complete reorganization of judicial power, and new rules governing crossing fees—which was a no-go and abrogated almost immediately. In the meantime, the city’s new masters prowled the streets wearing their white hoods, which is how they identified themselves. Woe to whoever refused to wear it. Even the king was forced to adopt it.

All of this was too much for people of good sense, meaning most Parisians, who wanted only that the excesses of the Cabochiens come to an end. To do that, the Burgundians were in the worst position, since they had, after all, offered their help to this bloody rebellion. That left the Armagnacs. Their troops were stationed near Paris and simply waiting for their moment, and now it had arrived. They attacked and chased out the Burgundians.

Two months later, on August 4, the Cabochiens tried again to start an uprising. At the Place de Grève they gathered, and speakers urged the people to fight back against the Armagnacs. A voice boomed out from among the crowd: “He who desires peace, let him line up on the right!”

Instantly, everyone ran to the right side of the square. This was devastating to the Cabochiens, of course. The most enraged among them made their way to the Hôtel de Ville, and there prepared themselves to fight one last if futile battle. However, in the meantime, both Caboche and Jean the Fearless had already fled Paris and were nowhere to be found.

They would have their revenge at Agincourt on October 25, 1415, when the French army—or more exactly the Armagnac cavalry—was decimated by the English army. Precisely one year after this defeat, a kind of victory for the Burgundians, Jean the Fearless met secretly with Henry V, the English king, at Calais. The two men would share the world and their ambitions: the Burgundians would not oppose the conquest of Normandy by the English, and the English would leave Paris to the Burgundians.

* * *

On the night of May 29, 1418, at two in the morning, eight hundred Burgundian knights entered Paris by means of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés Gate and awoke the inhabitants.

“Get up, good people, and arm yourselves! Long live the king and the Duke of Burgundy!”

Jean the Fearless’s soldiers made their way into Saint-Pol, nabbed the poor mad king, decked him out, plunked him on a horse, and led him through the streets of the city like a marionette wearing a crown. Only half conscious, Charles VI smiled benevolently at the crowds, seemingly unaware of the terrible events that had shaken the capital. The jubilant crowd welcomed the Burgundians, now sure that they would liberate them of the king’s bad ministers, bring about a new prosperity, and push back forever the specter of misery. Hordes of people armed with rusted lances and clubs attacked and pillaged the opulent homes of their former masters with a single cry: “Kill them! Kill the traitorous Armagnac dogs!”

* * *

In all the commotion everyone had forgotten about the dauphin, Charles, a boy of fifteen and the sole male heir. In these hours of drama, only one man had kept a cool head and thought about preserving the dynasty: that was Tanguy du Châtel, the new provost of Paris. He rushed across Paris to the Saint-Pol palace, bursting into the room in which the dauphin was lying on his bed, terrified by the events that were taking place all around him. The provost threw a blanket over the shoulders of the prince and took him toward the Bastille, where a number of the evening’s survivors were gathering to protect themselves from the wrath of the Parisians. Several hours later, the dauphin emerged from the fortress by exiting through an unguarded side door. The future Charles VII, disguised as an ordinary citizen, wearing a poor, grimy cloak and a simple hat, surrounded by a small troop of loyal soldiers, went through the defenses at a full gallop, abandoning the city to its latest spasm of violence.

A prince without a crown and apparently without a future, Charles could not yet know that he would rebuild his kingdom, but be forced to do it elsewhere, or that he would need to fight for eighteen years before he could reassert his authority over Paris.

In Bourges, which he made into his capital, the dauphin declared himself the sole repository of power.

“Only son, heir to, and successor of his majesty the king and through that by reason and by natural right the rule of the kingdom falls to me.”

By letter, he made his stand against the illegal regime in Paris. “We forbid anyone from obeying letters from the rebels, who have murdered the king’s chancellor and seized the great royal seal, or any letters aside from our own, sealed with our private seal and signed by our hand.”

Charles called himself the “master of the realm,” but in Paris Jean the Fearless controlled the crazy king and in Normandy the English king assumed the title of king of France. The country was divided and torn, and no one could predict who would win this war between the princes.

In Paris, it was a free-for-all. Armagnacs or anyone who resembled them were immediately dispatched. The leaders and officers were locked up in the Bastille and there in a nightmare scenario dreamed up by the executioner, a man named Capeluche, the prisoners were called forth one by one by name. They had to exit their cell by means of a low door, forcing them to bend down to pass. With the swing of a well-aimed axe their heads were lopped off and rolled away. Count Bernard d’Armagnac was among those who perished, struck down by Capeluche’s axe blow. Down the winding streets of Saint-Antoine ran rivers of blood, which didn’t seem to bother the artisans very much. This would not be the last time they would witness this kind of thing.

Jean the Fearless, on the other hand, began to worry about all the blood. He knew from experience that the patience of the Parisians was not inexhaustible. To show his good faith he ordered Capeluche’s arrest and had him beheaded, hoping thereby to put a stop to this frenzy on the part of the Burgundian partisans.

* * *

The next July 14 was a holiday in Paris. Jean the Fearless and Queen Isabeau of Bavaria entered the city and were greeted by a populace certain that now it would see an unbroken period of peace and security.

Jean the Fearless would not enjoy his victory for very long. A year later, on September 10, 1419, a meeting was organized in Monterau, in Île-de-France, between the dauphin and the Duke of Burgundy. The tension between them was palpable and the rancor unyielding; voices rose quickly and Tanguy du Châtel, the counselor to the young Charles, drew his sword and plunged it into the stomach of Jean the Fearless.

Premeditated murder? An act of spontaneous passion? A well-organized ambush? This would be discussed for a very long time, but the successive executions of the Count of Armagnac and the Duke of Burgundy canceled each other out. For the moment, it was the king of England who emerged the winner.

By the Treaty of Troyes in 1420, Charles VI agreed to rule with his son the dauphin and offered his daughter, as well as the kingdom of France after his death, to King Henry V.

A little more than a year later, Henry V and Charles VI rode through Paris side by side. One can only imagine the surprise and incomprehension of its citizens. Which one was actually the king of France? It was a viable question, for Charles was only a shadow, barely a symbol, and Henry was his successor, king of France and England, the most powerful monarch of the West. But the dreams of humans are subject to their mortality. In the month of August 1422, Henry, thirty-six years old, was struck down by dysentery. Weakened and suffering indescribable pain, he took to a bed in the keep of the Château de Vincennes; a hermit told him to prepare for the end. He commended his soul to the Lord and passed the governance of France to his brother John, the Duke of Bedford. Having accomplished this, he died. There was some debate as to how to get rid of the body. To return it to Westminster, an embalmer was sought, but no practitioner of this delicate art could be located. So the body was boiled and he made his final trip across the Channel in the form of a disarticulated skeleton, carefully arranged in little packages of whitened bone.

Seven weeks after that, in October, Charles VI died as well, carried off by a mysterious illness. Learning of the death of his father, the dauphin immediately pronounced himself king of France under the name Charles VII. On All Saints’ Eve, he entered Saint-Étienne Cathedral in Bourges, dressed in royal robes, made of vermeil and gold-encrusted ermine, and wearing lace-up boots stamped with fleurs-de-lys.

For the followers of the young king, the realm’s true capital remained Bourges, at least so long as the English occupied the banks of the Seine and a good part of their territory. And indeed the list of the territories now controlled by the Duke of Bedford was quite impressive: more than half the kingdom, including Bordeaux, Normandy, Champagne, Picardy, Île-de-France, and Paris. And he kept under his influence the territories of Philippe the Good, son of Jean the Fearless: Burgundy, Artois, and Flanders.

Each of the two enemies, the Duke of Bedford and Charles VII, headquartered in their respective territories, plotted to conquer the entire nation, inaugurating a series of battles, sieges, captured towns, the occupation of forts, all of which submerged the countryside in endless fighting, sowing death and causing famine and disease.

* * *

Finally, the boyish and frail Charles VII wisely took advantage of the bravura and tenacity of Joan of Arc—who after all might have been his half sister—who had been transformed from a shepherdess to a warrior inspired by God to accomplish the reconquest of throne and territory.

From Avranchin to Picardy, the provinces rose up against the English occupation. On April 13, 1436, in Paris, alarm bells called the population to revolt and the streets were barricaded. Barrels filled with dirt and overturned carts became barricades and traps, isolating the English troops. Through the neighborhoods bands of enemy archers moved aimlessly, leaderless and looking only to save their own skins.

At the same moment, the soldiers of the king surrounded Paris and liberated Saint-Denis. By carefully orchestrated rumor, the French made it seem as if their army was prepared to attack from the north. The English rushed in that direction while the main body of the French troops made a sweeping movement and entered the city by the Saint-Jacques Gate, in the south.

The city’s population enthusiastically welcomed the French soldiers. At last, they thought, the hour of their liberation had arrived. In a dramatic reversal of direction, the English mobilized their last troops around the Bastille, hoping that the thick walls and imposing appearance of this fortress would give them a chance to regroup and counterattack. This was a desperate maneuver as well as a futile one: the proud citadel quickly surrendered.

The officers of the king went to Notre-Dame to hear a Te Deum, while as a sign of a return of abundance, a procession of a hundred carts filled with wheat entered the city. Soon afterward, heralds went through the streets to announce that the peace the king desired was at hand.

“If any among you have been unfaithful to His Majesty the King, all is forgiven. This applies to those absent as well as present.”

The forgiving king threw a veil of forgetfulness over all the years that had passed, and those who collaborated with the occupier—those who called themselves “the repudiated French”—were categorically given amnesty. Charles VII rebuilt his kingdom on clemency.

His generosity had limits, however. During all these events, he had not left Bourges, though he consented to receive a Parisian delegation that had come to importune him to come back as quickly as possible to Paris, traditional capital of French kings. The king listened without responding. In fact he had no desire whatever to return to a city of which he had so many terrible memories and that in earlier years he had fled, a city that deep down he believed had been definitively disloyal to the crown.

Still, Paris was Paris. After hesitating for a year and a half, Charles VII finally made his solemn entrance into Paris, on November 12, 1437. To celebrate this reunion so devoutly wished for by the Parisians, and to glorify the union of the sovereign with his historic capital, the church bells rang at full throttle, flowers were strewn in the street, banners hung in the windows, and joyous throngs packed themselves along the passage of the brightly colored parade.

What became of the Château de Vincennes?

At the beginning of the year 1661, Cardinal Mazarin, prime minister to the young Louis XIV, was nearing the end. His legs caused him agonizing pain and he coughed frequently. After having purged their patient quite extensively, his doctors determined that the air of Paris was harming him. He was taken to the Château de Vincennes, where it was said that he breathed better. The man nonetheless breathed his last breath in the month of March. At the same moment, the court settled itself there on a temporary basis, the Louvre having burned in part and the roofs over some of the galleries having collapsed.

Louis XIV redid the pavilion that Louis XI had built there, but his heart was in Versailles, and this took him away from Vincennes. During the Revolution, the château was turned into an arsenal. In 1948, the records division of the French military settled there.

In 1958, just after he had been elected president of France, General de Gaulle resisted moving into the Élysée, which he found small and an unworthy place to welcome foreign heads of state. He therefore considered very seriously putting the heart of French political power in the Château de Vincennes. Eventually he gave up on the notion.

The buildings entered a period of obsolescence. The keep seemed on the verge of collapse and was closed down in 1995. A dozen years later, the château was completely restored; twenty thousand blocks of stone were replaced. It reopened to the public as an example of Parisian medieval architecture.

To the sound of trumpets, eight hundred archers and crossbowmen entered the city, announcing the arrival of Charles VII, who appeared wearing a long gold-and-azure cape thrown over his armor, seated on a white steed that was covered with a blue velvet blanket covered with fleurs-de-lys. He acknowledged the jubilant crowd with a timid wave of the hand.

The king did not remain long. Three weeks later, he left Paris and returned to Bourges, from whence he continued to organize the war against the English.

* * *

Charles VII’s successor, Louis XI, also kept his distance from Paris, though he was well aware of the city’s strategic importance. Château de Vincennes offered him a place from which the city could be monitored. After Henry V’s death in its keep, the tower was deserted, perhaps because it recalled too well the English occupation and the Plantagenet claim over France. Henceforth the keep would serve as a prison. Despite his tough, businesslike manner, Louis XI preferred comforts that were of a somewhat less austere nature. In 1470, he had a charming little pavilion constructed on the southwest corner of the wall. He also restarted work on the château’s chapel, which is a truly sublime example of late fifteenth-century architecture—le gothique flamboyant—featuring a nave of dizzying proportions. The architecture of defense was no longer the thing. The Hundred Years War had concluded twenty years before and the English holdings in France had been taken back; all that remained in English control was the port of Calais. What remained was the war against Charles the Reckless, the Duke of Burgundy, who lacked powerful allies to back him up and therefore fought a losing battle. In 1477, Burgundy was reattached to the country without a fight.

Moreover, customs now so little involved war that when he was doing a tour of Vincennes, reviewing the gentlemen of his court, Louis XI became aware that not one of them was wearing fighting gear. He determined to give each of them a writing case.

“Since you are no longer in a state to serve me with arms, serve me with your pen,” the king told them.

Was this a rebuke or a premonition of the growing importance of communication and hagiography?

Nonetheless, while Louis XI did make war he made even greater use of treaties, alliances, and inheritances. But by the end of his realm France was more or less unified. His son, Charles VIII, would look outside his realm toward Italy, where there were territories to be conquered. Indeed he wanted to take the kingdom of Naples and soon enough would cross the Alps in pursuit of that goal.