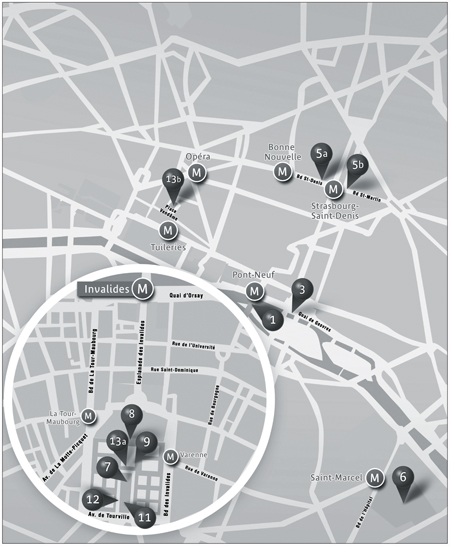

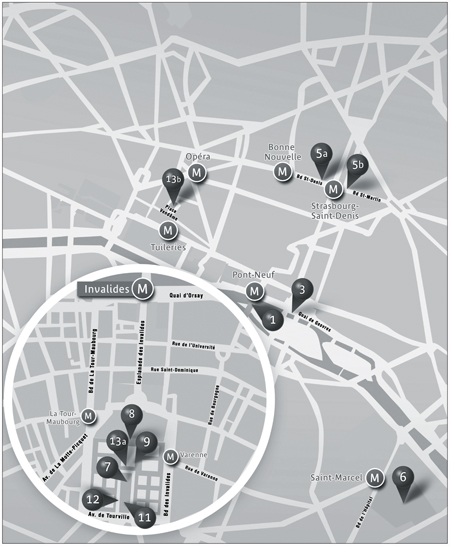

1. The Pont-Neuf. 3. The Quais of the Seine. 5a. The magnificent Saint-Denis Gate. 5b. And the modest Saint-Martin Gate. 7. The church of Les Invalides. 8. A bas-relief sculpture of Louis XIV on horseback, at the northern entrance to Les Invalides. 9. The Marquis de Louvois’s mark on Les Invalides. 11. Napoleon’s tomb. 12. And Napoleon’s original stone tomb, outside Les Invalides. 13a–13b. Napoleon’s statues.

Seventeenth Century

Invalides

The Price of the Great Century

The Invalides Métro stop is pretty gloomy. Though it leads us into the magnificence of the Grand Siècle, it does so by means of dim and somber corridors. Little matter. Once you reach the surface you discover the grandeur that Louis XIV sought for Paris.

In this part of the Left Bank, somewhat off-center from the city’s heart, there was once nothing but mud and swamps that belonged to the Saint-Germain-des-Prés Abbey. The name of the Grenelle field and the subway stop Varenne, which isn’t far, designate pretty much the same thing: as we’ve seen from the days of the Gauls, it was a rabbit warren, a field deemed unfit for farming, which explains why this vast space remained fallow for so long.

Louis XIV himself dismissed putting the Hôtel des Invalides on this spot as the “King’s big idea.” And when it came to grandeur the Sun King knew a thing or two about big ideas. He understood that a religion that centered on him was a religion for France, and he himself was the most energetic instigator of monuments built to his glory.

In 1669, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the superintendent of royal buildings, sketched out a few ideas for Paris: “Plans to continue everywhere—Arc de Triomphe, for the earthly conquests—Observatory for the skies—Grandeur et magnificence.”

The municipality of Paris financed the two arcs de triomphe dedicated to the king, raised up in the place of two gates that were sacrificed to a general program of beautification for the city. The arch over the Saint-Denis Gate was built to honor the victories in Flanders; and the more modest one over Saint-Martin Gate was built in commemoration of the conquest of the Franche-Comté—the former “Free County” of Burgundy.

It would be unfair to see these triumphal arches—whether initiated by the city or by the king—merely as monuments to the grandeur of the monarchy. A true effort was under way to make the city more secure and at the same time a better place in which to live.

In the Paris of the seventeenth century, the most beautiful private homes, ornaments of art and architecture, could sometimes be found on dilapidated streets and muddy lanes, places characterized by misery, crime, and disease. Many Parisian streets were a jungle of haphazard construction of levered wood and precarious chimneys. In their darkened corners gangs of thieves were ready to pounce upon respectable people who had lost their way. They all had their tags. The Rouget Band had their red coats; the Grisons wore gray; the Plumets sported large plumed felt hats. All of them inspired fear among ordinary people.

Paris was a swarm of activity, its ways and byways crammed with hawkers and traffic—water carriers, fowl merchants and their wicker baskets, heavy tipcarts filled with grain. To get anywhere you had to thread your way through all the confusion of wagons, carts, and herds of cattle heading toward slaughter. It was not an easy place to be a pedestrian. An artist named Guérard did an engraving of the streets of Paris and rendered in them the anxieties of the pedestrian.

TO WALK THE STREETS OF PARIS, KEEP YOUR EYES PEELED

LISTEN FOR EVERY SOUND, LET EVERY NERVE BE STEELED

TO AVOID BEING HIT, RUN OVER, OR CRUSHED,

BECAUSE IF YOU CAN’T MAKE OUT IN THE FRAY:

“WATCH IT! WATCH IT! OUT OF THE WAY!”

FROM ON HIGH AND UP FROM BELOW, YOU WILL BE MUSHED.

Construction along the riverbanks had been part of the Parisian landscape since time immemorial: the river quays were an endless work-in-progress. The centuries had brought with them some improvements, and Henri IV and Louis XIII had in their respective times tamed the banks, particularly along the Louvre and on the Place de la Grève, thanks to stone walkways large enough to permit pedestrian traffic and more particularly strong enough to contain the waters in the event of flooding.

On the Right Bank, stretched between the Quai de la Grève and the Quai de la Mégisserie a long stretch of ground became a field of mud in even the lightest rain: the carts that went down to the river there regularly get stuck. To have done with this hazard, the king demanded of the Marquis de Gesvres in 1664 that he build a wharf between the Notre-Dame Bridge and the Pont-au-Change. It carries the name of its builder and the subway stop on the 7 Line, at the Châtelet station, was built using the arches that support it. If you look from here toward Mairie d’Ivry-Villejuif, you will note that the vaults are slightly lower. These are the seventeenth-century foundations.

Eleven years after its construction, the work was completed with another quay, between the Notre-Dame Bridge and the Place de l’Hôtel-de-Ville, which would be given the name Le Pelletier when he was the provost of the merchants (the two wharfs would be joined in 1868 under the single name of Gesvres). On the Left Bank, similar work would be undertaken, as represented in particular by the construction of the Quai de Conti.

* * *

As befitted a sovereign, Louis XIV initiated and tracked these projects, though frankly without great enthusiasm. At heart the king didn’t much like Paris, and he never had much faith in Parisians. This was one reason that he finally moved away from the capital to set up his court and government at Versailles. He remembered too well how humiliated he had been in Paris as a child. The Fronde—the name given to the civil war that took place in France during the Franco-Spanish War—had nearly toppled the monarchy; no one had believed that a boy of eleven would one day rule the land and members of the nobility took advantage of the uncertainty. His mother, Anne of Austria, the realm’s regent, decided to flee Paris.

The night of January 5, 1649, was Epiphany. The streets of Paris were empty, though windows were lit up and everywhere there were celebrations. In the Palais-Royal, the feast went on until late in the evening. The queen had her piece of galette des rois—the traditional Epiphany cake—and found the bean, and hence she was given a cardboard crown. Everyone was amused.

Shortly after midnight, the queen retired to her quarters and prepared for bed. A minute after she had lain down she got up, woke up her two sons, Louis and Philippe, and using a back stairway went out into the gardens through a secret door. There were waiting three carriages, ready to take them all far away from Paris.

News of her sudden departure spread quickly through the court and created consternation, for everyone was commanded to follow the queen. Several hours later that same night, long processions of carriages filled with hastily attired men, disheveled women, and sleeping children took them deep into the countryside.

Waiting for them at the end of this exhausting late-night trip was the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which to sleepy eyes looked like a dark ship with crenellated towers emerging from a frozen sea. Nothing was readied for the royal guests; the rooms had been emptied for winter and were freezing cold. Only the king, his brother, their mother, and Cardinal Mazarin found modest camp beds. Everyone else was forced to make do with rough pallets set on the floor.

In the crowded corridors of the château people milled, including a good many of the kingdom’s nobles; everyone was in a foul mood. Worried-looking courtiers, dressed in clothes that were less than fresh, mourned the loss of their comfortable Parisian homes and exchanged the latest gossip from the capital. The royal flight had created stupefaction. Despite his young age, His Majesty was looked upon as the father of his subjects and the protector of his nation, the sovereign with divine right whose mere presence was reassuring and comforting. With him gone, fear filled the vacuum—fear of the unknown, fear of future calamities. For its part the Parliament endlessly debated about how to react. Finally, it was decided to send a delegation to Saint-Germain to beg the regent to return the king to Paris. But when these men arrived at the château the queen curtly refused to receive them, without even attempting to keep up appearances and spare anyone’s feelings.

* * *

During this time the Hôtel de Ville had become a place where prominent citizens and rebellious nobles came to rub elbows. Feasts and dances took place in the salons, as befitted a society more keen on pleasure than on fighting. But the Parisians also revealed their aggressive nature, in this case by pointing cannons at the walls of the Bastille prison and firing six shells. This was mostly symbolic; the shells did little damage to the thick walls. Having done this, they took over the fortress without further incident. This was deemed a great victory, and in order to celebrate it, the elegantly dressed women and grand-looking men then emptied the prison wine cellar.

The queen’s pout lasted for seven months. She then returned to the Palais-Royal.

* * *

Two years later, Paris was humiliated yet again. On the night of February 9, 1651, the rebellious princes of the Fronde, appalled by the idea that Anne of Austria and her son the king might once again leave Paris, closed the city gates and mobilized a militia. That night no one would either enter or leave the city. But were the king and his mother even within the city’s walls? Might they have already escaped? To reassure everyone, Gaston d’Orléans, young Louis’s uncle, sent the captain of the Swiss Guards to the Palais-Royal with the mission of locating the king.

Is “boulevard” a typical Parisian word?

In 1670, Louis XIV ordered the demolition of Charles V’s ramparts, which were by now doubly useless—both because of the evolution of military technique and because of the urbanization of the neighborhoods outside the walls.

On the Right Bank, the ramparts were replaced by a wide avenue that went from the Bastille to the Madeleine on which people could walk.

The French word boulevard belongs to this period and was intended to describe this novelty. It is therefore very typically Parisian. It has a double origin: it comes first from the Dutch bolewerk, which means “bastion” (from bol, for mortar, and woerk, “work”). The term therefore designated ramparts. Later, when the fortress wall was torn down, it gave place to open space filled with trees. The Parisians called these boules—from bol—verts, to acknowledge their greenery. Hence boulevards were places to relax, stroll, and daydream.

Their suspicions were well placed. The queen had indeed determined to leave Paris again, fearing the return of civil war and a popular revolt among the masses. The arrival of the Swiss Guard had prevented her from executing her plan. The child-king, who was already dressed, was to have gone to bed and pretend to be in a deep sleep, the sheets drawn up to his chin to hide his clothes. At that moment in came the Swiss captain. He looked into the royal chamber and to his profound relief found the young monarch asleep there. By this point a crowd had gathered before the palace and demanded to see their young king in person. They were allowed entry. Silently and respectfully, a line of workers, washerwomen, and porters, their faces animated by concern, filed past the royal bed to observe the sleeping child. Several women made the sign of the cross over the blond curls of the king and murmured prayers on his behalf, before heading back out into the street, reassured.

Louis never forgot the humiliation of all this, and one can understand a little better why he wanted to make Paris seem like less of a prison. This was partly to improve it and partly to weaken it. Ample courtyards and generous boulevards would replace fortifications and impasses. The city would be opened up.

Louis XIV reserved his architectural whims and artistic enthusiasms for Versailles. However, he made one exception in Paris, one that he hoped would benefit the many soldiers wounded or mutilated in the cause of France’s military glory. The king did not want to forget those to whom he owed his victories: the rank and file who were mobilized for his costly campaigns. Today you can see the golden dome of his gratitude rising up nearly 350 feet over the vast space, a Gallo-Roman battlefield to which has been restored some sense of serenity: the Invalides.

* * *

The Invalides served a practical purpose as well. When Louis XIV, comfortably settled in his carriage, crossed Paris he used the Pont-Neuf, which was crowded with poets, vagabonds, journal salesmen, and bear baiters. And veterans of the wars as well, many of them reduced to begging. The king may have felt his heartstrings pulled by the sight of sleeves without arms, legless cripples, blind or mutilated men—all the poor bastards who had had their bodies broken on the field of honor and now lived a life of misery.

Morally, the king may have been only slightly moved by the sight of these men; politically, he was aware of the danger that they posed. They represented the flip side of the military decoration, and were a little too conspicuous. He who so adored going to war wanted to preserve its image as a grand adventure, and to cover over the fact that it also could lead to misery. His idea was therefore to take these invalids—these shadows on his sunny reign—away from the center of Paris and find a place to hide them from public view.

Eventually, the recommendation was to build the structure on the Grenelle plain. The fact that the plain was so isolated from the rest of Paris suited the king. This way these poor souls would be less visible. A dazzling golden dome would deflect the suffering of those beneath it.

* * *

In 1674, Louis XIV formally announced the purpose of the buildings that he had had constructed. They were to be a “royal residence of grandeur and space, capable of receiving and housing all the wounded officers and soldiers, whether elderly or young, and to assure sufficient funds to feed and care for them.”

The king had good reason to worry about the wounded, for there was always a war going on in one part of the land or another, producing a seemingly endless crop of them. On August 11 of that year, for example, forty-five thousand men led by the Prince de Condé battled sixty thousand Dutch and Spanish soldiers under William of Orange. Seven thousand Frenchmen were killed in this battle, which lasted for a day and a night and took place near Mons, roughly twenty-five miles from Brussels. Once again, it wasn’t the bodies left on the field of battle that concerned the king; it was the thousands of survivors who came home without legs, or eyes, or arms.

Of the eight monumental architectural plans that were proposed, the king selected the one by Libéral Bruant, the architect who had already designed and built the hospital at Salpêtrière. The construction of the Invalides corresponds to the same period as the hospital, which housed some forty thousand indigents, beggars, and sick who, at least according to the king, represented a threat to public health and security. This reflected a way of thinking that might send chills down the spine of anyone who lived in mid-twentieth-century Europe. Still, here was Louis XIV’s principal legacy for Paris: freed of its beggars, its wounded safely shipped off to the outskirts.

* * *

The plan for the Invalides was simple and magisterial: on these twenty-five acres would be built a grand court surrounded by smaller ones, with rectilinear buildings and in the center a church dedicated both to the king and to the wounded.

In October of 1674, the first men entered their new abode. In a militarylike ceremony, the veterans were welcomed by the king himself, accompanied by François de Louvois, minister of war. The veterans were not bitter; they applauded His Majesty, doubtless relieved to know that henceforth their housing and food would be covered.

Room and board, yes, but not, as it turned out, much freedom. Discipline was strictly enforced at the Invalides. Military exercises were de rigueur, wine and tobacco were forbidden, and religious observance was required. These poor handicapped men were forced to submit even in their retirement to military regulation.

The soldiers were housed four or five to a bare room, while the officers shared a room with one or two others and at least had a fireplace. Designed to house fifteen hundred pensioners, the building was soon home to six thousand, despite a rigorous admissions process and strict regulations.

Today, after passing through the cour d’honneur you are immediately plunged into the middle of these men destroyed by war, as the interior has on the whole been remarkably well preserved: the staircase, beams, and corridors remain as they were at the end of the seventeenth century. On the ground floor were the refectories for the wounded soldiers, as well as their dormitories. Today the refectories house the Museum of the Army, but one can still make out in its vast proportions a sense of the original purpose, while admiring the frescoes glorifying Louis XIV’s military victories.

Going up to the first floor takes you into the rooms that faced the central gallery. The stairs guiding you there are very gradual, a reminder that they were designed for those who could barely walk. Once you reach the first floor you can see names and drawings engraved onto the walls, as well as the results of the small occupations that were designed to keep the men from being bored. Thus if you head to the northwest toward the Quesnoy corridor, behind the statue of the Grenadier, you will see, drawn over the right parapet, a shoe whose flat heel seems to mock the fashion for red heels reserved for the nobility under Louis XIV. It’s a piece of graffiti from the Grand Siècle. There’s another one next to it, over the parapet to the right as you take the western corridor.

The main entrance is located in the northern pavilion, along with the administrative offices and the governor’s apartments. And in front of this entrance stands the wooden horse, a feared form of punishment for the inmates of Les Invalides. For the slightest infraction, the smallest fault, one was put in it for several hours and subjected to humiliation by fellow soldiers and visitors. For yes, there were visitors. Les Invalides became a favorite destination for excursions and Parisians came here both to be reacquainted with the misery of others and to listen to the old soldiers tell their war stories. At bottom what one found at Les Invalides was an open book of history, ready to be flipped through. The young women who visited sang the latest mournful song:

Tell us pretty lady

Where your husband be.

He’s gone away to Holland

The Dutch took him from me …

And so the old veterans told their rapt listeners about the war in Holland, where they went to die in the polders of the Low Country or to get shot up by the English while fighting alongside the Dutch (coalitions were always forming and re-forming).

What of Louvois remains in Les Invalides?

Louis XIV, astride his horse, occupies center stage—at the northern entrance to Les Invalides—and though his face was chiseled off during the Revolution it was repaired to perfection under the Restoration.

But the Marquis de Louvois ingeniously found a way to insert himself into the cour d’honneur. If you look at the pediments under the roofs you will see that they are comprised of coats of arms dedicated to military glory. On the eastern façade, the one on the right if you turn your back to the statue of Napoleon and move over six pediments, starting with the emperor, you will see an oeil-de-boeuf that represents a wolf observing the courtyard with a fixed stare. That’s it: the wolf looks—or, in French, le loup voit, hence “Louvois.” And that is how the marquis left his mark on the work to which he had dedicated such a large part of his life.

“More than eighty ships and sixteen Dutch firebomb boats bearing a hold filled with powder were involved in the battle,” recalled one crippled sailor. “The cannon mouths were moved to the hatches, and the sailors on the fireboats approached the ships, setting fire to the hulls and then scampering off in little dinghies, having set fire to their own ships. It was a sea of fire! And in this furnace the vessels were rammed, their mouths spitting fire and their masts cracking. Good God! Cannonballs filled the air, and the flames were everywhere, and grapple hooks dug deep into the ship rails, and my ears were filled with the cries of the wounded!”

* * *

But if Les Invalides were operational, meaning functioning as hospice, hospital, and—the men needed an occupation—uniform manufacturer, one last building completed the ensemble and that was the Church of Saint-Louis. Libéral Bruant, the architect, hesitated and procrastinated over that design; he was never satisfied with the plans and kept coming back to a construction that he always felt was imperfect. Minister of War Louvois was irritated by the delays but waited for two years. Finally he sent the indecisive Bruant packing and replaced him with one of his students, a young man of thirty named Jules Hardouin-Mansart.

Why does Napoleon lie at Les Invalides?

Transformed into a Temple of Victory during the Revolution, the church still preserves today the sanctuarylike role it played for the army, its men, and its history.

Napoleon had military respect for Les Invalides, which he visited regularly, calling upon the wounded, and organizing within its walls the first award ceremonies of the Legion of Honor; he also allocated to it a significant amount of money.

In December of 1840, brought back from Saint Helena, the remains of the emperor were quite naturally placed in the church in Les Invalides. King Louis Philippe hesitated, however, as to the final placement of the famous tomb. After two years of waffling, His Majesty ordered the architect Louis Visconti (creator of the fountain of Saint-Sulpice Church) to build a monument. A deep pit was dug under the dome. The emperor, wearing the green uniform of the Huntsmen Guard, was not placed there until April 1861, however, under the reign of his nephew Napoleon III.

The tomb, carved from blocks of purple porphyry, the stone of emperors, was placed atop a large green-granite base from the Vosges region and decorated with laurel crowns and inscriptions of the emperor’s victories. Around him in the crypt are the tombs of members of his family, including the Aiglon—the Eaglet—Napoleon’s oldest legitimate child, as well as those of other military men who have served France, including the generals Vauban, Turenne, Foch, Juin, and Leclerc.

On the outside of the church, on the western side, you might perhaps see under a tree a modest and neglected stone tomb, which is the original stone tomb in which the emperor was brought back from Saint Helena.

A bronze statue of Napoleon also stands on the first floor of the building, easily visible from the cour d’honneur. Commissioned by Louis Philippe in 1833, the sculptor Charles-Émile Seurre designed it to sit atop the Vendôme column. The statue was taken down in 1863 by Napoleon III and replaced by what he felt was a more regal image—that of the emperor wearing a Roman toga. The statue of Napoleon in his two-pointed hat, his hand stuck into his vest, was first exhibited in the Courbevoie traffic circle. After the fall of the Second Empire, this bronze Napoleon was thrown into the Seine, thus escaping the Prussians in 1870 and the Commune in 1871. It was fished out of the water in 1876 and forgotten about for thirty-five years. Finally, in 1911, it was given its place in Les Invalides.

In fact, it was not only on the aesthetic front that Bruant faltered but also on the issue of prerogative and precedence. How was he to design a religious space with both royal and popular functions? How could it accommodate both the Sun King himself and his most humble servants? Hardouin-Mansart found a solution. In his design, the structure doubled, and in an architecturally coherent way. The nave would be dedicated to the religious needs of the common soldier; under the cupola would be housed the royal chapel.

Louvois took matters in hand, allocating more and more funds to the work, and monitoring its progress. Nearly every day he arrived at the worksite and despaired at how slowly it was all proceeding. Every detail had to be seen to—a new element added to the frescoes, a skylight realigned, a correction made to the coats of arms engraved into the stone, a heraldic symbol added.

“You will have to hurry if you want me to see the dome completed,” said the minister to the architect.

Alas, he died in 1691, long before the building was finished.

The construction of the church took more than thirty years. After Louvois’s death, the king himself took charge of it. He would sometimes visit it incognito; having his carriage stop some distance off and accompanied by only a few courtiers, he would walk the rest of the way on foot. Guided by Hardouin-Mansart, His Majesty came to inspect some effect of the statuary or the deployment of an architectural rib.

Finally, the tallest dome in Paris was finished in 1706, when the Sun King was no more than a toothless old man whose face was the color of yellowed ivory.

But the wish expressed so long before had endured. Les Invalides remained a hospital for soldiers, though the number of pensioners had risen from six thousand to one hundred thousand. The place that the Sun King had wanted as a visible sign of military glory still concealed under its golden dome the sordid and sinister side to war, the misery and the agony of men sacrificed at the altar of the nation’s grandeur.