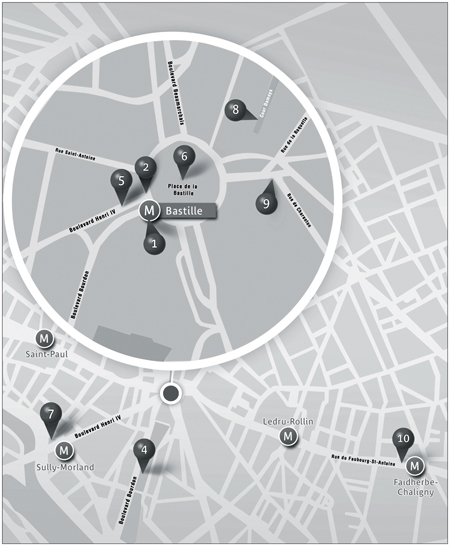

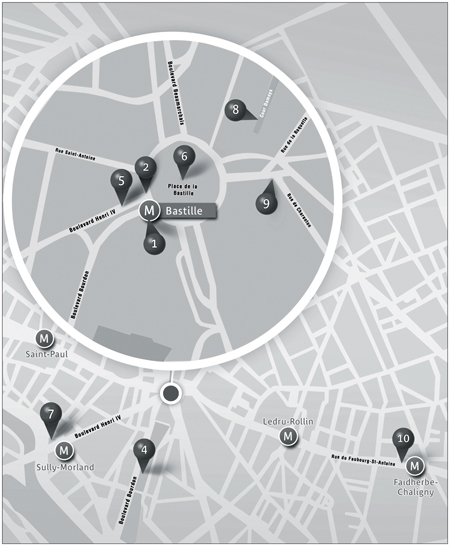

1. The Bastille Métro stop. 2. The corner of Boulevard Henri IV and Rue Saint-Antoine: a brown paving stone indicates the precise position of the old fortress. 4. The Arsenal Gate was built on the site of the Bastille; some of its stones are remains of the military fortress. 5. The last of the Bastille’s dungeons. 6. The Golden Génie. 7. One of the eight towers of the Bastille, discovered during construction of the Métro and rebuilt in Henri-Galli Square. 8. The artisans of the Saint-Antoine faubourg. 9. The house on the corner of Rue de Charenton and Place de la Bastille, where an enormous barricade was set up during the Revolution of 1848. 10. At 184 Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine, a small fountain dating from the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The Eighteenth Century

Bastille

The Fury of the Faubourg

The Bastille Métro stop does a meritorious effort of evoking the Revolution, attempting to inspire revolutionary nostalgia among Parisians on an outing: a brightly colored fresco retraces the great moments and period images evoke the fortress as it looked in former days. Most particularly, on the platform for Line 5, one can see some yellowing stones. These were part of the foundations of a wall from the Bastille, discovered in 1905 when the subway tunnel was being dug. Outside the subway entrance, at the corner of Boulevard Bourdon, you can see another segment of the old fortress wall.

We’re lucky that even these modest remains survived, because nothing of the Revolutionary Bastille is left. Today when you say “Bastille” you generally mean the opera house. This heavy glass-and-stone bunker, which has aged prematurely, looms over the square with its inert mass. Built to commemorate the bicentennial of the fall of the Bastille, the opera house has already started to crumble and would not require a revolution to be demolished.

To find what remains of the past, it is useless to look on the opera side of the square or at the Génie of the Bastille, a golden symbol of liberty stuck atop its green column. A better bet is to go to the corner of Boulevard Henri IV and the Rue Saint-Antoine and look down: a brown paving stone indicates the precise position of the old fortress. On the façade of the building at number 3 on the square a map indicates its massive form. Toward the Seine, the Arsenal Gate evokes the moat around the walls and some of the older stones are the remains of the military edifice. Finally, at the end of Boulevard Henri IV, also in the direction of the Seine, the base of the Tower of Liberty—one of the eight towers of the Bastille—was discovered during construction of the Métro and rebuilt in Henri-Galli Square.

* * *

Let us go back to the Bastille, which was a catalyst for popular hatred well before 1789. Long before that it had been a symbol of opposition to royal absolutism and of princely ambition. As we saw, Parisians had risen up and taken it in 1413.

In 1652, when rebellious princes tried to strip power from the young Louis XIV, the Bastille loomed up in importance for a second time. On July 2, the Prince de Condé, the leader of the princely revolt, marched on Paris at the head of his army. During the early morning hours a savage fight broke out at the Saint-Antoine Gate. Condé troops confronted the firepower of the royal infantry; the result was bodies everywhere. Musket shots rang out and houses were burned. Very quickly the royalist troops, the soldiers of the Fronde rebellion, and the city’s inhabitants were caught in a confused melee. Marie-Louise d’Orléans, known as the Grande Mademoiselle and a cousin to the king, appeared before the Bastille; its doors opened to her and she was received with honors. She climbed the stairway that led to one of the towers and by means of a telescope observed the scene.

In the distance, toward Bagnolet, she saw the red and blue uniforms of the Royal Army. At her orders the Bastille’s heavy cannons were turned toward these troops and fired. The retort was so violent that it shook the walls; the crenellations of the high towers vanished in a cloud of acrid smoke. The shells whistled and landed with devastating effect among the royal divisions, mowing down an entire row of knights. The Bastille bombardment upon the king’s men had its effect: in disarray, the marshals loyal to Louis XIV temporarily called a halt to the assault. For a moment Paris was in the hands of the rebellious princes.

* * *

Well before July 14, the Bastille had therefore become a symbol—a place either to occupy or to tear down. No one knew exactly what went on inside it, but everyone was quite sure that it represented arbitrary authority and was therefore to be feared and hated.

Generally prisoners held there—never more than forty, sometimes fewer—were treated with respect. These prisoners were often young nobles who had broken certain rules but who had the right to a kind and gentle form of incarceration. To be more at home, they brought in their furniture, gave dinner parties, and occasionally were accorded permission to leave for the day, so long as they returned to sleep in the prison.

Voltaire, the author of a pamphlet that had displeased the authorities, was kept there for eleven months in 1717. Upon his release, he received a pension of a thousand ecus from the regent, Philippe of Orléans.

“I thank your Royal Highness for what you have seen fit to pay for my food, but I pray that you no longer concern yourself with my housing,” he responded.

Nonetheless, such largesse was not available to everyone. The archives reveal some pretty awful crimes. “I am sending you this man named F. He is a very bad subject. You will keep him for eight days, after which you can do what you will,” wrote Antoine de Sartine, lieutenant general of police around 1760, to the governor of the Bastille, Bernard de Launay. “Have the man named F brought in,” Launey wrote on the note, “and after the prearranged time ask M. Sartine under what name he would like himself buried.”

What horrors went on in there were only guessed at by the population of the Saint-Antoine faubourg. In the neighborhood streets over which loomed the shadow of the gray walls of the prison lived a group of artisans, and they were always quick to express discontent.

The fortress has long since disappeared but one can still walk about the faubourg and find a few back courtyards in which handmade craftsmanship lingers on. You can breathe in the odor of varnish and polished wood, as per the traditions. In the Damoye Court, at number 2 Place de la Bastille, you will find a representative passageway. The house on the corner of Rue de Charenton also offers a handsome vestige of this busy place: here is where an enormous barricade was set up during the Revolution of 1848, sealing off Saint-Antoine.

Everything changes quickly; the old furniture workshops have become popular bars and clubs, for this quartier has become one of the trendier spots in Paris. No longer do workers come home to their exposed-beam lodgings, filled with slightly twisted old furniture, but instead young professionals who have turned city living into a lifestyle.

* * *

In the eighteenth century the Saint-Antoine faubourg wasn’t quite like the other faubourgs. The term faubourg is of course completely Parisian. It dates from the late fifteenth century, derived from the Old French forsbourc, which means “outskirts” or “suburbs”—fors from the Latin foris for “outside.” But folk etymology has defined it as “faux bourg”—a fake town—to connote its status as a kind of “inner suburb.” Since the days of Louis XIV, Saint-Antoine had been the privileged place of poor artisans who had the right to work independently, free of professional organizations or guilds. Cabinetmakers, furniture makers, upholsterers, locksmiths, hatmakers: they all worked side by side and the stores, which often doubled as workshops, followed the shape of the winding streets that eventually emerged into Rue de la Roquette, Rue de Charonne, and Rue de Charenton.

All day long the neighborhood was crisscrossed by wagons and donkeys driven and ridden by farmers from outlying areas who came to sell eggs, vegetables, or fruit; by women who cooked in the open air near the wharves; by swarms of hawkers known for their aggressive vulgarity. The citizens who inhabited Saint-Antoine came from the outside and were always quick to spontaneously express their anger. One epidemic too many, a bad harvest, or an additional tax could lead them down the dangerous path from protest to rebellion.

And so it was that on April 27, 1789, the faubourg was in full boil. The source of it was the prosecution being brought against one Jean-Baptiste Réveillon, owner of a large painted-paper factory on Rue de Montreuil. Several days earlier, Réveillon, who was actually quite generous with the 350 workers in his employ, had made a series of propositions to the city of Paris to combat poverty. This businessman and amateur social entrepreneur thought that he had grasped the interconnections between the fates of nations and the lives of the poorest, and had devised a program to change society for the good. More dreamy than wise, more visionary than enlightened, he had proposed doing away with the tax on goods brought into the city, which could therefore be sold at a lower cost. That was fine, except that he also suggested lowering salaries, because the cost of living would now be less. Under the Réveillon Plan, workers who were earning twenty sous a day would have to content themselves with fifteen.

It was in the Saint-Marcel faubourg, located on the Left Bank, that a reaction to “Réveillion the Starver” first took place.

“Death to the rich!” shouted the crowd as it made its way to the Place de Grève (of course).

Before the Hôtel de Ville, an effigy of Réveillion was set on fire, and then a procession headed toward Saint-Antoine. Three hundred and fifty guards managed to maintain order during the night, but in the early hours of the morning the tanners of Saint-Marcel and the artisans of Saint-Antoine streamed out onto Rue de Montreuil. Réveillon and his family had long since fled, but his factory was systematically plundered, taken apart piece by piece, and his wine cellar emptied of its bottles.

Finally, after several hours, the police guards, joined by reinforcements, were able to push the crowd back. Stones were thrown from roofs and shots rang out. Soon twelve policemen and hundreds of protesting workers were killed, the bodies of the latter paraded around the faubourg and greeted with popular rage. No one yet knew it, but the world was going to be profoundly shaken. The Revolution had now started, and it had just known its most murderous day, despite the horrific violence that was yet to come.

Before number 184 Rue du Faubourg-Saint-Antoine you can still see a small fountain, dating from the beginning of the seventeenth century. More or less situated at the location of the Réveillon factory, it was the center of this émotion—to use the language of the Ancien Régime. This first “emotion” had claimed more than a hundred lives.

* * *

In the weeks that followed, from the sixth floor of the tower of the Bastille in which he was incarcerated, the Marquis de Sade called the people to rise up. Imprisoned by what was called a lettre de cachet—or “hidden letter”—written by his mother-in-law to the authorities and outlining his dissolute habits, the marquis wrote his One Hundred and Twenty Days of Sodom, a work in which he detailed every possible turpitude of his troubled soul. And when he had had enough of letting the pen run along the paper, he took hold of a long white metal pipe equipped with a little funnel which, when the urge arose, he attached to his bottom—a portable toilet in which he could more conveniently dispatch his excretions down below into the moat. With said instrument Sade formed a kind of bullhorn that he used to harangue the people of the faubourg.

“Good people! They are slitting the throats of the prisoners in the Bastille! Come immediately to our rescue!”

These cries for help were taken seriously by passersby, appalled at the thought of what must be happening behind those thick walls. Actually, however, the marquis was living large in prison, quite comfortably situated in two rooms in which he had placed his furniture and his personal library; he was eating so well that he had grown a little potbelly.

What was the Bastille?

To the east of the city, in order to protect the Saint-Antoine Gate, a bastille—or “bastion”—was constructed starting in 1370. This fortification offered a place of refuge for Charles V, who generally stayed in his nearby Saint-Pol residence. This “bastille Saint-Antoine” featured eight towers connected by walls that were nearly ten feet thick. The whole thing was surrounded by a moat that was more than eighty feet wide and more than twenty-five feet deep.

By the seventeenth century the Bastille’s military function was no longer relevant and Cardinal Richelieu had turned it into a prison in which to put his enemies. There was no need of a judge or jury to be thrown in the Bastille. A king’s order or a lettre de cachet was more than enough.

In 1788, the Chevalier du Puget, the king’s lieutenant at the Bastille, had already planned for the closing of the fortress and estimated that doing so would save forty thousand livres that could be added to the royal treasury, given that the king paid considerable sums to run the place: the salary of the governor, officers, soldiers, doctor, and priest. It was a large staff for a prison population that diminished year by year: nineteen in 1774, nine at the beginning of 1789, and only seven a few months later.

On the fourteenth of July, 1789, early in the morning, the storming of the Bastille took place—except that it happened at Les Invalides. For the nearly three months following the attack on the Réveillon factory, popular rage had continued to seethe, and the smell of powder still seemed to float over Saint-Antoine. Rumors true and false were rife. It was said that a plot was being hatched, but a plot by whom and against whom exactly? Against what? It was said that troops were being formed outside Paris to reestablish order. It was said that the harvest had been bad and that there would be severe food shortages.

On the previous evening several bakeries had been broken into and a militia had been formed, and alarms had sounded all night long. The population intended to defend itself against the mercenaries that were threatening to occupy Paris; some workers forged pikes, but it would take more than that; they needed guns. Guns were plentiful at Les Invalides. So that’s where people went. The doors were ripped open and the crowd seized thirty-two thousand rifles and several old cannons. Now they needed gunpowder.

“There’s gunpowder in the Bastille!” someone shouted.

“To the Bastille! To the Bastille!

In a swarm, the Parisians left Les Invalides and headed to the Right Bank, crossing the bridges and marching toward the old fortress. The idea wasn’t to take it—no one thought of that—but simply to raid it for its gunpowder and bullets.

When the Marquis de Launay, the governor of the Bastille, saw this human wave heading toward him he kept his cool. He was determined not to give way and simply open up his arsenal to a howling mob. A delegation sent by the Hôtel de Ville came to him and demanded that he give this citizen militia the ammunition they required. The delegation, consisting of the city’s highest officials, was received with great courtesy by the marquis, who even invited them to dine (probably as a way of gaining time until royal reinforcements could arrive). It was a pleasant enough meeting but it didn’t lead to anything. Launay refused to budge even if he did not also intend to fire upon the crowd, not so long as no one tried to break into the fortress. A second delegation was dispatched several minutes later, and then a third. They met with no greater success.

At one-thirty in the afternoon, the crowd around the Bastille became restless and threatening. The governor knew well that he could not sustain a siege; the proud old place was defended by only ninety-two veterans, most of them with war wounds, and commanded by about thirty Swiss Guards.

Nonetheless it was important that the rule of law be enforced and Launay, a rigid man with a deeply lined face, a poor pawn placed by destiny in a spot that exceeded his capacities, had his men fire on the crowd of enraged protesters who had seized hold of the chains on the drawbridge. A hundred attackers collapsed onto the paved stone.

In the afternoon, two detachments of the Swiss Guard, whose responsibility was to ensure the security of the city, changed sides and joined with the mob. These war-toughened soldiers had five cannons taken from Les Invalides that same day and fired them at the Bastille’s doors. A fire broke out, big enough to make the old veterans guarding the fort panic. They forced Launay to raise a white flag. The drawbridge was lowered and the crowd poured into the Bastille. In its joy, it liberated the prisoners, surprised that there were only seven in all, and, on top of that, that they little resembled the heroes of liberty who had been expected; rather they were small-time crooks and forgers. Still, the symbolism was what counted. They were carried out in triumph.

The poor Marquis de Launay was dragged through the streets before being decapitated with a knife by a junior cook. His head was fixed onto a pike and carried around the faubourg in triumph. This macabre ritual marked the population’s fury and resentment and in their way these were now implacable. There would be no going back.

In Versailles, Louis XVI was woken in the night by the Duc de La Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, and they proceeded to engage in a short scene with dialogue that could easily have been written by actor and playwright Sacha Guitry.

“Sire, the Bastille has been taken, the governor was murdered and his severed head was carried about on the head of a pike.”

“Ah, so this is some kind of rebellion, is it?”

“No, sire. It is a revolution.”

* * *

Two days later the demolition of the Bastille was begun. Eight hundred workers were involved—at twenty-five sous a day—to tear down what still seemed like the “bastion of tyranny.” The stones from it would be used to build the Pont de la Concorde—the bridge leading from the Place de la Concorde to the Left Bank—and several others. Some became souvenirs. One resourceful artisan named Palloy even made miniature fortresses out of them and sold them across France.

A year to the day after the storming of the Bastille, to commemorate the anniversary and to bring patriots together in a cause, a Festival of the Federation was organized on the Champs-de-Mars by La Fayette, commander of Paris’s National Guard. Sixty thousand delegates came from the country’s eighty-three départements to celebrate the unity of all France and King Louis XVI, who was placed atop what was called the Autel de la Patrie—the “altar of the country”—from which he swore allegiance to the nation before all the Parisians crowded on the embankment around it.

The last of the Bastille’s cells

Everyone now agrees that with the exception of several foundation stones, which are still visible in the Métro stop, nothing of the Bastille remains. Well, that’s a mistake. One cell does in fact remain, one of the cachots—sordid and lightless holes—that were to be found deep down in the fortress, where royal authority imprisoned the stubborn and the recalcitrant.

One day when I happened to be near the Place de la Bastille, I was talking with a friend who ran a bistro in the neighborhood, and who shared my passion for Paris. He took me down to the cellar of his establishment, which was called La Tour de la Bastille, and which in fact featured one of the Bastille’s cells, miraculously saved from revolutionary fervor. Later I verified what my friend had told me. He had been quite right; the stones and the shape of the wall confirmed it. I was deeply moved by the experience of entering this place. Standing amid all the bottles I felt as if I could hear the cries of prisoners and the boom of the July 14 cannons.

Today the bistro has been replaced by a restaurant called the Tête-à-Tête—and that may be gone as well—but the basement still contains the mystery and secrets of number 47 Boulevard Henry-IV.

In 1880, when it was necessary to choose a date to commemorate this festival, it was July 14, 1790, that was chosen, not July 14, 1789; in other words it was the date of reconciliation rather than that of civil war and terrible violence.

* * *

After the demolition of the Bastille, the history of the square on which it had once sat was one of failed meetings and missed opportunities, at least from the architectural point of view. On June 16, 1792, the legislative Assembly decreed that the spot where the prison had once stood should become a square with a column atop which would be a statue of Liberty. A month later the first stone was set. Then the project came to a halt due to aesthetic differences. The following year, a fountain that was supposed to represent nature’s charms was put in the place of the abandoned column.

What lies beneath the column?

History sometimes takes strange turns. To the 540 martyrs of the 1830 Revolution buried under the column were added several Egyptian mummies two or three millennia old.

Napoleon had brought the mummies back from the Egyptian campaign and they had been buried in a garden near the National Library on Rue de Richelieu, on the same spot where, after the Glory Days of July, the bodies of the killed were buried. When it was decided to bury these revolutionary heroes under the column, no one thought about sorting them and the bodies were simply dumped there. And thus it was that several pharaohs also lie under Bastille near the Saint-Martin Canal, which runs beneath it. Did the bark of Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead, take this watery path that connects the Seine to the Ourcq River to bear these princes and workers into the Realm of the Dead?

In 1810, Napoleon wanted to put up another fountain, a gigantic bronze one made from metal from the cannons taken during the Spanish insurrection. Somewhat oddly, this monument was to represent a giant elephant 260 feet high with water spurting out of his trunk.

The foundation was laid and a life-sized plaster model was made in 1813. After the fall of the empire, this imposing animal—one of the most incongruous constructions Paris had ever known—remained in its plaster form for years. The plaster began to crumble bit by bit, though an elderly guard continued to live inside one of the feet. In Les Misérables, Victor Hugo makes it the home of Gavroche, the kid who helps man the barricades.

Happily the plaster carcass was destroyed in 1846, and from the ruins of the pachyderm emerged an enormous pack of rats which terrorized the Saint-Antoine faubourg for a number of years.

In 1833, King Louis Philippe decreed that a column be constructed in the middle of the square, in honor of the fallen heroes of the Three Glories, meaning July 27, 28, and 29, 1830, during which Charles X was thrown off the throne in favor of a constitutional monarchy. The monument, over 175 feet high, was unveiled on April 28, 1840. At the top of the green column the aforementioned golden Génie, or “genius,” was to represent something that the Assembly’s deputies had wanted in 1792: it would stand for “Liberty that broke its chains and flew, and brought with it light.”

With cannons firing from the top of Montmartre, the Commune of 1871 tried to destroy the column, which for the radical Republicans represented a symbol of an alliance between a monarch and his people. The column withstood, as did the Republic.