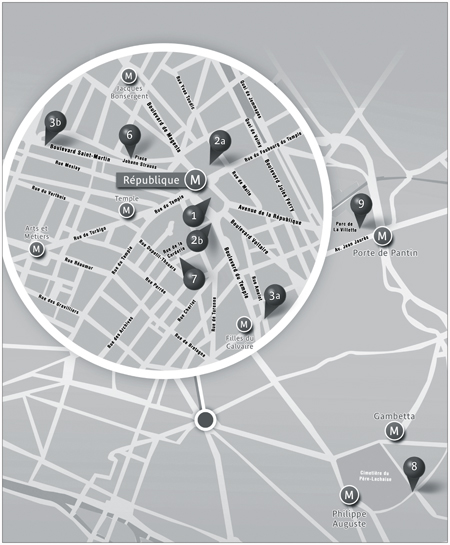

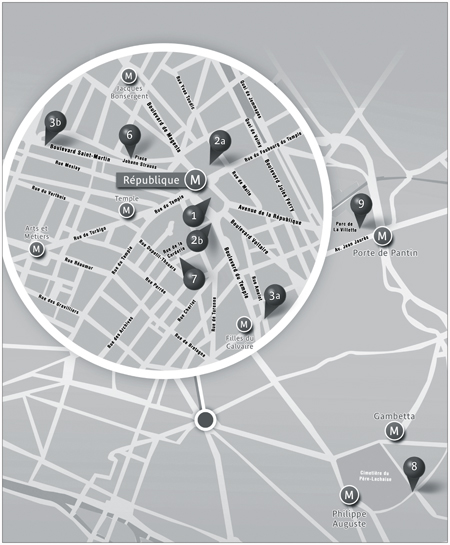

1. Madame la République. 2a. Boulevard of Crime. 2b. At 51 Boulevard du Temple, the Théâtre Déjazet. 3a. The Cirque d’Hiver. 3b. The Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin. 6. The Ambigu theater was spared, then destroyed in 1966 and replaced by a bank (1 Place Johann-Strauss). 7. 14 Rue de la Corderie, where the International Workers Association ordered the uprising of February 16, 1871. 8. Père-Lachaise cemetery, where Communard rebels were lined up and shot on May 28, 1871. 9. The Nubian Lion Fountain.

Nineteenth Century

République

In Five Acts and Dramatic Moments

When you come out of the Métro at République you find yourself standing at the foot of the weighty figure of Madame la République. In her revolutionary headgear—the so-called Phrygian hat—holding an olive branch, the Declaration of the Rights of Man at her side, her bronze gaze watches over popular protests for which she has been the guiding spirit for more than a century. Covered in black-and-white flags atop which are inspiring banners, she remains the mother figure for the Enfants de la Patrie. At her feet, on the stone pedestal, are the Three Virtues, symbols of the Republic: Liberté, symbolized by a flame; Egalité, as symbolized by the tricolor flag; and Fraternité, as represented by a cornucopia.

This monument, which is now an indispensable part of the Parisian political landscape, was placed here on July 14, 1884, and this secular form of the divine became the apotheosis of the then-new Third Republic, which seemed to have been victorious but which was still somewhat tremulous about what it had survived. The Commune had occurred a little more than a decade earlier, and the memory of what happened at number 14 Rue de la Corderie was very much alive. It was there that the International Workers Association ordered the uprising of February 16, 1871.

* * *

Once upon a time the Place de la République had been called the Place du Château-d’Eau, a large intersection at the end of Boulevard du Temple. After the Revolution, Paris’s two great fairs—that of Saint-Laurent on the Right Bank and the Saint-Germain on the Left—had declined. Boulevard du Temple then became the place for gatherings and festivals, particularly after the creation of theaters was no longer subject to the whims of official power. New playhouses opened in profusion along the enormous arc of the boulevard, and it became the center for entertainments for all segments of the population, aristocrats as well as proletariats.

The epicenter of the boul’ (as the boulevards were called) was to be found in the tight perimeter between the triumphal arches at Saint-Denis and Saint-Martin, and the former Rue d’Angoulême, which is today Rue Jean-Pierre-Timbaud; it went all the way to the Cirque d’Hiver, or “winter circus.”

This epicenter formed a true border of east and west. The rest of the boul’—toward Bastille on the one side, and toward the Madeleine on the other—was less festive. The aristocrats and the bourgeoisie feared venturing too far east into that side of town; and workers were hesitant about entering the western parts of town, which had been the stomping grounds of the Ancien Régime. One could easily sense this separation between worlds, so much so that the poet Alfred de Musset would look at the eastern ends of the boulevards from the west and say, “There are the Great Indies.”

The Château-d’Eau intersection was surrounded by enormous buildings and home to the fountain that was designed by Pierre-Simon Girard, from which the square and the street derived their name (“water castle”). It was on the Boulevard du Temple—intersection of all pleasures—that the first line of omnibuses, drawn by horses, was established in 1828, leading from Bastille to the Madeleine.

The fountain became too small for the new configuration of the square; it was dismantled and taken to La Villette in 1867, where it served as a watering trough for beasts being led to the slaughterhouse. Partly transformed, it can still be found in the park in La Villette, under the name Nubian Lion Fountain.

* * *

In the 1830s, the Parisian theatrical world was alive with activity and ferment. The heart of this universe of creative illusion was the Boulevard du Temple, which the local population jokingly called the “Boulevard of Crime,” because every evening in the various theaters and playhouses any number of actors were involved in stabbing, poisoning, and strangling one another, to the enormous pleasure of the paying public. Among the fifteen or so theaters on the boulevard, a few were so enormous that they could seat more than three thousand spectators. These included the Ambigu, the Porte Saint-Martin, the Théâtre Historique, and the Cirque Olympique; others were more modest in size, only seating around five hundred, such as the Funambules or the Délassements Comiques.

During the day street hawkers shouted out what was on the program that evening, offering a few tantalizing details; when night began to fall, under the trees along the boulevard—which offered a little cover—the ticket lines started to form. Soon it was dark and the cafés lit up, filled with those waiting for the performance to begin. Along the whole line of theaters were shops selling waffles, nuts, spiced bread, apple turnovers, or ices at two sous apiece. The brightly colored lanterns of the merchants threw flickering light on the pavement, and the frenetic sounds of their bells sometimes drowned out the voices of the barkers. And then suddenly the boulevard emptied out and the theaters filled. Not until the intermission would the Boulevard of Crime take life again.

In the playhouses the curtain rose. Audiences were generally noisy and prone to whistle whenever a scene didn’t please them, or to let an actor have it.

The uncontested star of the boulevard was Frédérique Lemaître, who triumphed at the Ambigu-Comique starting in 1823 in The Inn of the Adrets, a melodrama accompanied by music and ballet that he could turn to his advantage with his gift for improvisation and irony. The play had been a flop when it first opened but Lemaître, a giant of a man with a booming voice, turned his character, the bandit Robert Macaire, into a sort of comic murderer with a heart of gold.

“Killing snitches and police doesn’t mean I don’t have feelings,” he would declaim, to the applause of a delirious audience.

In 1841, Frédérique Lemaître had no male rival on the Boulevard of Crime. As for a female star, her name was Clarisse Miroy; the two of them were destined to meet. Clarisse triumphed in The Grace of God, a schlocky vaudeville warhorse which spectators at the Théâtre de la Gaîté had come to love. Each evening the same theatergoer sat in the same seat in the first row of the orchestra. And each evening he waited until Mademoiselle Clarisse had made her entrance before noisily dropping his cane. Invariably the appalled audience would turn toward the clumsy idiot and see Frédérique Lemaître, impassive-looking, his lips pursed under his little black moustache. One night, the cane didn’t drop. Clarisse and Frédérique began an affair that lasted for thirteen years.

Their love finally ended in a scene worthy of melodrama. After having left her famous lover, Clarisse wanted to return to him and was rejected in turn. Heartsick and jealous, she put a large dose of laudanum, a popular poison at the time, in his water glass. He managed to survive drinking it, though this act of attempted murder did little to revive his feelings for Clarisse. Frédérique forgave her but would never see her again.

* * *

In 1848, the carefree world of the boulevard, like the rest of Paris, was afire with revolutionary fervor. Louis Philippe had ruled the French for nearly eighteen years. The monarchy had gradually lost its grip, mired in economic problems and scandals. Everything seemed to be in league against the king—the harvest had been poor and the price of bread rose sixty percent, and a disease from Ireland had destroyed the potato crop. Paris feared famine.

Properties fell into disarray, industries were ruined by a stock market crash; intellectuals with dreams of the republic and nostalgic Bonapartists all focused their anger on an elective system that gave only a small minority the right to representation. Isolated and inflexible, Louis Philippe refused to consider any kind of reform agenda.

Public meetings of more than twenty persons were forbidden. That was easily gotten around. Instead of having meetings, people held banquets. The government couldn’t forbid that kind of gathering. After a rather frugal dinner came heated revolutionary rhetoric.

The biggest of these banquets was planned to take place on February 22 in Paris. A procession mixing students, workers, and artists was to march from the Place de la Concorde all the way up the Champs-Élysées, where a dinner would be held and after that the usual speeches. East and west were to meet. Starting in the morning, several processions started to make their way through Paris; the police and the army held their collective breaths.

The day passed in relative calm, but the next evening, singing “The Marseillaise,” a large group headed toward the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which was then located on Boulevard des Capucines. The crowd approached the soldiers who were guarding the building and surrounded them. One of the crowd’s leaders, a bearded man of some stature, tried to strike an officer with the torch he was carrying. A rifle shot rang out, and the torch shook, then fell to the pavement. Panic ensued. The soldiers started firing in every direction, and in the end sixteen lay dead. Their bodies were piled onto a wagon and paraded around. A menacing crowd followed behind this macabre procession.

“Vengeance! To arms!”

From that moment the throne was doomed. On February 24, while an icy rain fell on the city, barricades were formed on all the city’s boulevards; people huddled around braziers, attempting in vain to ward off the cold of a freezing fog that seeped into clothing. The leaden skies were the somber décor of a revolution in progress.

Having taken refuge in his palace in the Tuileries, Louis Philippe sought comfort from his generals, whom he asked whether the city could still be defended.

When no one replied, the king understood. He wearily went to his desk to sign his act of abdication.

The republic was formed. The temporary government asked the theaters to reopen, hoping to have things return to normal as quickly as possible.

But drama was not just taking place on the stages. The fashion now was to form clubs—which were pronounced cli-oobs—where people could express their agitation, and they could be found in every quartier of the city—home to anarchists, socialists, and neo-Jacobins, who gathered to rub elbows and listen to fiery, antibourgeois speeches.

One evening, in one of the biggest of the clubs and also the most extremist—it met in the great hall of the Conservatoire on Rue Bergère and was presided over by the fearsome professional agitator Auguste Blanqui—those gathered showed in great detail how the bourgeoisie were the only ones to benefit from the sweat of the people. It was all a form of theater, and thus somehow fitting that Eugène Labiche, a young writer of vaudeville plays, rose to speak. Standing on the raised platform covered with a green rug, at which also sat the severe-looking members of the club’s officers beneath the tricolor flag and its motto, “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité,” he harangued the workers in the audience.

“Citizens, by simple accident of birth, of which I am innocent, I happen to belong to this shameful caste of society that I cannot sufficiently curse. I nonetheless think it an exaggeration to believe that it drinks the sweat of our proletarian brethren. Allow me to cite a personal example that I hope may change your opinion, for if you love justice, O fellow citizens, you should not love truth any the less. I live in an apartment on the fifth floor and lately I had some wood brought in. The virtuous citizen who, for an agreed fee, ventured to climb my stairway to bring said wood to my apartment got so heated in the act of doing so that sweat poured off his features with their manly determination. To put it bluntly he was swimming in perspiration. Well, I happened to taste a little of that sweat and I can tell you that it tasted awful.”

A disapproving murmur accompanied the final words of this theatrical declaration. When Labiche, his head held high, slowly descended the steps from the stage, a few were so outraged that they rushed up to him, intending to use their fists to make him understand that they found this kind of humor inappropriate. Luckily the writer Maxime du Camp happened to be in the room, and somehow was able to get his colleague out of there more or less in one piece.

* * *

Several months later, in December 1848, the election of Prince Louis Napoleon to the presidency of the new republic cooled tempers. Once he had moved into the Élysée palace, the new chief executive didn’t disappoint those who longed for a return to peace. He banned the clubs and leaned on the army to prevent any potential insurrection.

The mandate the prince was given was for a four-year, nonrenewable term. However, by means of a coup d’état he held on to power. On the morning of December 2, 1851, people awoke to find that posters had been put up all over Paris, carrying an appeal and signed Louis Napoleon. “If you believe in me, give me the means to finish the great mission that I have started on your behalf…”

The prince’s methods were already apparent: the army occupied the city, the Assembly was dissolved, and a number of deputies had been arrested. The speed with which this had happened precluded immediate reaction.

Only the next day did the city shake off its torpor. More than seventy barricades were constructed. The army replied with terror. On the boulevards, drunken soldiers, panicked by the threatening crowd, opened fire. Ten minutes of continuous shooting cut down innocent passersby, children, and old people. Bodies were everywhere, with the wounded trying to crawl away. The crowd howled its reaction. Two hundred and fifteen were killed. The horrified crowd was cowed into submission.

What could you find along the Boulevard of Crime?

There is first of all Marcel Carné’s 1945 film, Les Enfants du Paradis, one of the great film masterpieces of all time, which realistically re-creates all the poetry of the Boulevard of Crime, with its actors and audience and pimps.

There are also more tangible traces. Located at number 51 Boulevard du Temple, the Théâtre Déjazet, built in 1851, escaped demolition by Baron Haussmann. Called in succession the Folies-Mayer, Folies-Concertantes, and Folies-Nouvelles, the playhouse was bought in 1859 by Virginie Déjazet, one of the most celebrated actresses of her time. Closed in 1939, it was turned into a movie house, then in 1976 it would have become a supermarket had the arts community and concerned citizens not mobilized to save it.

To the east, the Cirque d’Hiver on Rue Amelot was another survivor. Built in 1852, it was located at the far end of the Boulevard of Crime. Also turned into a movie theater right at the beginning of the development of the septième art, or “seventh art,” it became a circus in 1923 and was used by all the great names of the time—Bouglione, Fratellini, Zavatta.

To the west, the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin was also one of the rare survivors of the Boulevard of Crime. First an opera built by Marie-Antoinette, it became a battleground during the Commune. The theater as it looks today was rebuilt in 1873.

A year passed. Now calling himself Napoleon III, the former president of the republic decided it was time to redesign Paris. His idea was to turn the city into a modern city—open, hygienic—as well as to eradicate the poorer quarters where the ragged people lived and clean up the rough neighborhoods that could so easily turn into revolutionary hotspots. Baron Eugène Haussmann, the prefect of the Seine, aided the cause, creating wide boulevards that made it both more difficult for barricades to be constructed and easier for troops to be brought in should there be a rebellion.

Given the spirit of order and discipline he was trying to instill, the emperor was concerned about the Boulevard of Crime and wanted to have done with the trouble that was always brewing there. The boulevard would be torn up. In 1854, Napoleon III had the Prince-Eugène military barracks constructed nearby. Today they are called the Vérines Barracks of the Republican Guards, named in honor of a lieutenant colonel shot in Germany during the Second World War.

The architectural battering ram used by Baron Haussmann turned the city into an enormous worksite. What emerged from it was a city with large avenues. A decree pushed the boundaries of the city all the way to the old fortifications: Auteuil, Passy, Montmartre, and Belleville were integrated into it, bringing the number of arrondissements to twenty. The Place du Château d’Eau, now called Place de la République, was enlarged in 1862. Most of the playhouses on the Boulevard of Crime disappeared.

The biggest theaters refused to die and simply moved elsewhere. The Théâtre Historique became the Châtelet; the Cirque Olympique became the Théâtre de la Ville, also located in the Place du Châtelet; the Gaîté left the Rue Papin and became the Gaîté-Lyrique. The Folies-Dramatiques moved to Rue René-Boulanger, and later housed a movie theater during the 1930s. The Ambigu was spared, then destroyed in 1966 and replaced by a bank. The demolition order was signed by André Malraux.

During its eighteen-year existence, the Second Empire made Paris into a bourgeois playground. Wars took place somewhere else—in the Crimean or in Mexico; the stock market was in full expansion and rewarded bold investors; fortunes were made and industries developed; people went dancing in the Saint-German faubourg, which had become the central artery of the luxurious lifestyle.

The greatest moment of this era in France was without doubt the Exposition Universelle of 1867. A palace built of iron, glass, and brick was constructed, covering the entirety of the Champ de Mars. A colossal example of ephemera, with its audacious modern design, the construction was the heart of the new Paris. On April 1, a glorious day, the fair was opened by the emperor, while rays of sun played off the glass. Beginning in the early hours of the morning an immense crowd of people had massed around the entrances. Brought together under one gigantic roof were all the arts and technical achievements of every civilization on earth. There were the latest-model locomotives, Indian teepees, astounding demonstrations of electrical power, and Japanese houses made entirely of paper. Forty-two thousand exhibitors came to show off their creations and inventions. Each country wanted to display its power: the English exhibit took the form of a large golden pyramid, representing the volume of gold extracted from Australian deposits. More worrisome was the Prussian exhibit, which featured an enormous Krupp cannon. In the joyous atmosphere of the exposition, however, no one wanted to acknowledge this menacing note.

The city’s dark corners and sordid dead ends were subjected to demolition crews. Now Paris was run through with wide avenues, and glorious streets were bordered with impressive buildings whose stone façades were crowned with slate cupolas. At night, gaslights illuminated Paris and turned it into a perpetual playground. The center of the new nightlife were the great boulevards, charming open spaces that began at the Madeleine and stretched all the way to Château d’Eau, passing through the magnificent neighborhood of the opera house, the ultimate symbol of Haussmannian ambition. Here was a promenade dotted with cafés in which, with their comfortable and upholstered sitting places, one could find both celebrities and true elegance.

With Second Empire Paris in the grip of pure gaiety, balls and feasts were held, each one trying to outdo the other in grandiosity. There was no time to sleep, as was observed with amusement by the worldly chronicler Henri de Pène: “Dinner was set for 7:30, the play at 9 o’clock, and the balls began at midnight, then supper at 3 or 4 in the morning. Then a little sleep after that if it could be had and if there was time for it.”

Emperors, kings, princes, and industrial tycoons gathered in this boisterous and fun-loving capital. One was no longer sure to whom to give way when the Russian czar crossed paths with the sultan of the Turks, the queen of Holland met with the king of Italy, and the king of Prussia rubbed elbows with the khedive of Egypt. It seemed in all this euphoria as if mankind was heading toward universal peace.

* * *

Three years later, in 1870, the carefree Second Empire was destroyed by the Franco-Prussian war, the product of the Bismarckean dream of a greater Germany. In the month of July, Paris prepared for war with great enthusiasm. The soldiers were wildly cheered as they marched along the boulevards. Women created a pantheon to the heroes of tomorrow; patriotic cafés and inns poured out their cheap wine to the men in uniform.

What lay ahead might have been predicted. The poorly trained French armies were surrounded by the Germans and the emperor himself taken prisoner in Sedan. On Sunday, September 4, the hot sun of late summer made Paris radiate under a deep blue sky. Learning of the military debacle, a huge crowd massed at the Place de la Concorde and seized control of the Second Empire’s symbols.

The empress was forced to flee with her last group of loyal followers, the ambassadors from Austria and Italy. This small group crossed the Diana Gallery all the way to the Flore Pavilion and went into the Louvre, immediately engulfed by the museum’s enormous Great Hall. Soon she found herself facing Géricault’s enormous canvas, The Wreck of the Medusa, with its writhing bodies.

“How strange it all is,” she murmured, tears rolling down her cheeks.

She exited by the small door onto the Place Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois. A carriage waited there, and the fallen empress got in and was taken away from the city at a slow trot. For a while Eugénie took refuge with her American dentist, who lived near the Bois de Boulogne. Eventually she went into exile in England.

* * *

The republic had proclaimed the end of the war but had not succeeded in stopping it. The capital was bombarded, burying entire families in the remains of their houses. The roofs of Les Invalides and the Sorbonne collapsed. Confusion reigned. The Prussians tightened the vise and soon the city was cut off. The siege had started. Paris being Paris, people still went out to eat in restaurants in which, stuffed and cooked, its tail sticking straight up and a sprig of parsley arrayed about the muzzle, rat was served.

In February, the Prussians arrived and marched down a deserted Champs-Élysées. Paris had put on its cloak of mourning; black crepe floated in the breeze on the balconies of city halls in every neighborhood. The victorious troops did a little tour of the capital and then departed.

Paris was enraged. Starting in the month of March, the Commune rebellion had reached nearly every neighborhood. Red flags were raised up against the gray skies. Exhausted, disoriented, and demoralized soldiers raised their rifles into the air and broke ranks. Soldiers and civilians joined forces as if at a joyous country fair.

However, some French troops remained loyal to governmental authority and they indulged in a debauch of killing. In Montmartre, the Luxembourg Gardens, and elsewhere, people were bludgeoned with rifles and shot; sometimes an entire line of Communard prisoners were simply lined up and machine-gunned. The bodies of the dead piled up in front of the Panthéon. On May 28, the last of the rebels were taken to Père-Lachaise Cemetery, lined up against the back wall, and shot. By the end of May, order was definitively restored, at the cost of twenty thousand dead. Survivors were deported by train.

As Adolphe Thiers put it, “Either the Republic will be preserved or it will not.” And thus it was on January 30, 1875, under the presidency of Marshal de Mac-Mahon, that the laws of the Third Republic were adopted by the Assembly—by a single-vote majority: 353 to 352.

* * *

Theater in Paris managed to survive the Boulevard of Crime’s demise. At the Saint-Martin Gate, the fashion was for grand spectacle. In 1875, Around the World in Eighty Days, based on the novel by Jules Verne and adapted for the stage by Verne and Adolphe d’Ennery, enjoyed huge success. People flocked to see the live elephants, boa constrictors, a locomotive made of cardboard spewing out clouds of smoke, a ship on the high seas, an attack against redskins, a Hindu religious ceremony, Javanese dances, and the multitude of figures used in exotic tableaux vivants.

Other neighborhoods attracted a new audience. In Montmartre, on Rue Victor-Massé, the Chat Noir cabaret started a shadow theater in 1886 and it became famous throughout Paris.

The Éléphant remained the Chat Noir’s most famous and celebrated show: a white screen was illuminated and a cartoonish-looking black man approached, pulling a rope; he pulled and pulled and then disappeared, and the rope seemed to stretch out indefinitely; then came a knot, another rope, and finally an elephant deposited what the barker called an “odiferous pearl.” From this “pearl” grew a flower that opened right before the eyes of the spectators. Curtain!

From the unexpected success of this theater in miniature arose a new kind of art; an entire room was reserved for it. Henri Rivière, the inventor of the world of silhouettes, was constantly coming up with new ways to animate his shadows. An evening at the Chat Noir became the thing. Balkan kings, British noblemen, and provincial factory owners all religiously attended. Sometimes some illustrious visitor would ask to be allowed behind the scenes after the show. This always upset Rivière, who had provided his crew with a way of responding to the request. They duly informed said illustrious visitor that any false move would release a large cloud of dust that could easily ruin his elegant clothes. A piece of the décor skillfully manipulated would knock his expensive hat off and send it flying. Most often at that point the curious guest pushed matters no further and beat a hasty retreat.

* * *

While the Boulevard of Crime was sacrificed to progress and modernity, another kind of crime—a far more real kind—grew up in the vicinity of the future Place de la République. Starting at the end of the nineteenth century, the dance halls on this side of town lined the joyous road to perdition. One could dance at République, forgetting about sorrows in the quadrille of rouge-cheeked young girls. A mixed world of interlopers got caught up in music that was intoxicating. On any given Sunday or holiday, a wide cross section of bourgeoisie, day laborers, working girls, and country hicks all caught sight of bare legs.

Prostitution thrived here. Decked out in vulgar rags, rouge-smeared, exhausted by the endless activity on their bit of pavement, they sold themselves for a few francs. Looks could be deceiving. You could never be sure that beneath the frippery was more than pliant flesh. If she took her client’s wallet and he looked like he might protest, she was more than capable of sticking a knife between his ribs.

These tough women, and the thieves, pickpockets, and pimps around them were all called “apaches.” With their hats worn at an angle, their tattooed biceps, a cigarette stuck in the corner of their mouths, they terrorized the bourgeoisie and fought each other viciously over the smallest point of honor. These bands were completely hierarchical; daring and defiant, they guarded their turf jealously.

“We in Paris have the advantage of having a tribe of Apaches for whom the Ménilmontant or Belleville heights are the Rocky Mountains,” wrote a journalist in 1900. The analogy was clear. The young thugs were like the American Indians at the time in that they refused to be turned into good little workers of the Industrial Revolution, to sacrifice themselves in the name of progress.

The city’s poorer neighborhoods were located in the east, which is where Ménilmontant or Belleville were located; the Place de la République was the natural meeting place with the west.

If these poor people sometimes refused to go along with the new social order, it was perhaps because they knew they would be mere pawns—exploited, used up, and spit out by the lords of the Nouveau Régime.

The world of the apaches had its heroes and its heroines. In 1902, the newspapers devoted nearly all of their columns to a story that fascinated Parisians. The central figure was a prostitute with almond-shaped eyes and a round face crowned with large curls of dirty-blond hair, which explained her nickname, Casque d’Or (“Goldilocks” wouldn’t be a bad translation).

And what happened to Casque d’Or?

Amélie Hélie posed for amateur photographers, shacked up with a few millionaire lovers, and worked as a lion tamer in a circus before finally ending up selling women’s stockings in Bagnolet. She married a worker whom she no doubt kept entertained with stories of her youth. She died, poor and forgotten, in 1933, at the age of fifty-three.

Neither Manda nor Leca returned from French Guyana, to which they had been sent. Manda died in the penal colony; as for Leca, after paying his debt to society, he worked until his death as a mason in Cayenne.

Casque d’Or took the apaches into legend. A melodrama called Casque d’Or or Les Apaches de l’Amour had a highly successful run in the playhouses on the boulevard. And in 1952 Jacques Becker produced his immortal film Casque d’Or, starring Simone Signoret and Serge Reggiani.

Amélie Hélie—for that was Casque d’Or’s real name—was twenty-two in 1900. One night, while dancing the Java in a music hall near the République, she met a young worker named Marius Pleigneur. It was love at first sight—a bond formed by lost children. Marius proved jealous and possessive. To keep Casque d’Or for himself he joined her world. Marius gave up his low-wage jobs and became Manda, the terror of the boulevards, head of a gang known as the Orteaux, named after the street of that name. The unfaithful Casque d’Or drove him to despair. She threw herself into the arms of a Corsican named Dominique Leca, leader of the Popincourt, a rival gang. War broke out along the outer boulevards. As in a classical tragedy, everything unraveled with astonishing speed. On January 9, 1902, Leca was hit with two bullets. The doctors managed to save his life. Several days later, leaning on the arm of Casque d’Or, he emerged from the Tenon Hospital in the Twentieth Arrondissement. Manda was waiting for his rival and went after him with a knife, wounding him. The Corsican managed to utter the name of his attacker. Both Leca and Manda were arrested and sent off to a penal colony.

The apaches disappeared in the bloodbath that was the First World War, along with the workers and farmers who made up most of the soldiers.

Casque d’Or, Manda, and Leca lived and loved in the neighborhood around the Place de la République, for that was now its name. In 1879, the year in which the republicans triumphed once and for all over the royalists and the Bonapartists in municipal and senatorial elections, the name of Place du Château d’Eau was changed. It became the home of the imposing-looking statue that still presides over it.

The République had been shaken but had not fallen. Soon it would shape the nature of Paris’s institutions.