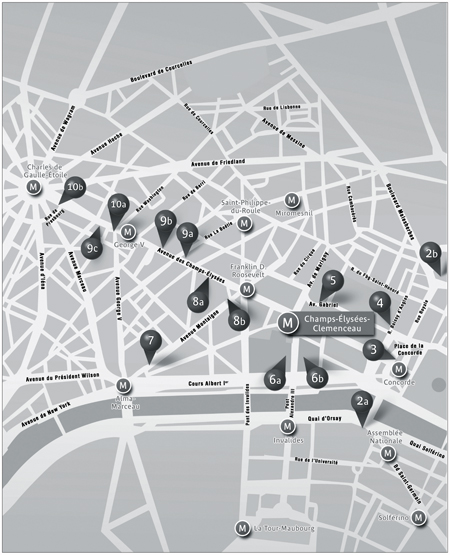

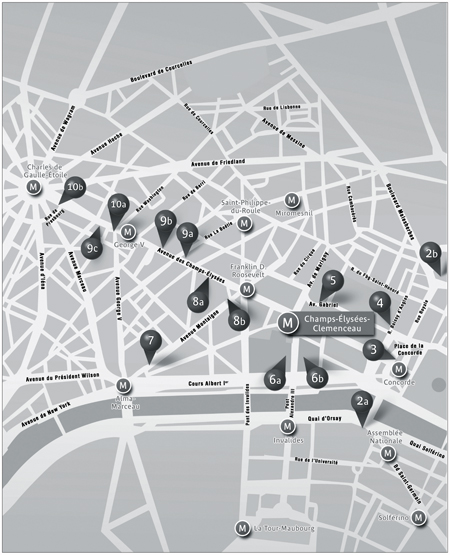

2a. Across the river from the Place de la Concorde, the Palais-Bourbon, now the home of the National Assembly; its twelve Corinthian columns were intended to reflect those of the Church of the Madeleine (2b), as if in a distant mirror. 3. The Place de la Concorde. 4. The Place Louis XVI. 5. The entrance to the gardens of the Élysée palace. 6a. The Grand and Petit Palais. 6b. Statues of General de Gaulle, Winston Churchill, and Georges Clemenceau. 7. At 15 Avenue Montaigne, the art deco façade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. 8a. At 25 Avenue des Champs-Élysées, the former home of the Marquise de Païva. 8b. The hotel Marcel-Dassault, home to the Artcurial, is another example of twentieth-century luxury and distinction. For examples of twentieth-century architecture, see: 9a. The art deco building (formerly the Virgin Megastore) at 56–60 Champs-Élysées; 9b. The art nouveau façade of the Claridge (74–76, Avenue des Champs-Élysées); 9c. The former Élysée palace, which became a bank, at number 103. 10a. The Louis Vuitton store at 101, Avenue des Champs-Élysées. 10b. The Publicis drugstore at number 133.

Twentieth Century

Champs-Élysées-Clemenceau

The Ways of Power

The Champs-Élysées-Clemenceau stop on the Métro could easily have been called “Champs-Élysées-Clemenceau-De Gaulle-Churchill,” since statues of these two great figures of the Second World War are joined here with that of the Tigre—“the Tiger”—as Georges Clemenceau was called, transforming the former president of France into a quasi-allegorical character. This stop lies beneath the intersection at the foot of Champs-Élysées, a place that has been the scene of some of the bloodiest conflicts in French history. It should have had a different history, one of harmonious and mutual understanding. The Grand and the Petit Palais, located here, serve as examples, for they were constructed during the Exposition Universelle of 1900, symbols of exchange and cooperation between peoples.

At the top of the avenue, and leaving aside the Arc de Triomphe, which was built to glorify Napoleon, the Champs-Élysées entered into history through the Great War, World War I. In 1920, when the idea of building a tomb for the body of an unknown soldier who had died on the fields of glory first came up, the Chambre des Députés proposed placing the tomb in the Panthéon. The government and the president of the republic, Alexandre Millerand, had another plan, which was to celebrate Armistice Day (November 11) by taking the heart of Léon Gambetta, the architect of national defense following the fall of the Second Empire, and putting it in the Panthéon. This offered a way of commemorating the second anniversary of the Armistice and the fiftieth of the republic, which was formed in 1870, at the same time.

These two projects, one put forward by the chief executive and one by the Chambre, resulted in a political schism: the Left wanted to glorify Gambetta; the Right wanted to venerate the common French foot soldier, the poilu. To avoid open confrontation, President Millerand offered a compromise: the heart of Gambetta would go to the Panthéon and the Unknown Soldier to the Arc de Triomphe in the Place de l’Étoile. This would happen on the same day. No one was really satisfied with the arrangement. The hard-core Left refused to take part in what it deemed a “military festival,” and the reactionary wing on the Right howled against the idea of paying homage to the “layman” Gambetta.

Nonetheless, on the morning of November 11, 1920, a solemn procession composed of war-wounded; widows, a mother and an orphan, all of them victims of the conflict, accompanied the coffin of the Unknown Soldier, which was placed on a gun carriage. The procession made a symbolic stop at the Panthéon, where, at that very same moment, Gambetta’s heart was being transferred. Then it made its way to the Arc de Triomphe.

Real and symbolic at the same time, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier permitted the French to express collective grief, allowing families to weep openly over the loss of a father, a son, or a brother, lost somewhere in that great idiocy that was the Great War, a victim of the trenches, or gas, or bombardment. Politics had turned the Arc de Triomphe into a tomb, but also into a powerful symbol: the Tomb of the Unknown Solider closed off the arch. No longer could soldiers march through it. It was a fitting close to the war to end all wars. In September 1940, German troops, marching down the Champs-Élysées, proved that assertion an illusion.

On August 26, 1944, General de Gaulle walked down the same stretch of the Champs-Élysées to the Place de la Concorde.

“Ah, the sea,” he apparently murmured when he saw the size of the crowd that was on hand to watch this victory parade.

From windows, balconies, rooftops, hanging from ladders and clinging to lampposts, Parisians wanted to take part in this historic moment, as the wind gently fluttered the tricouleur. The cannon salute that erupted in the Place de la Concorde, an echo of the final battle, created a brief wave of panic. People regained their composure and headed toward Notre-Dame Cathedral, where a final gun salute was fired.

In 1970, added to the Place de l’Étoile was the name Charles de Gaulle, who had just died, and in so doing the government mingled together the memory of the Unknown Soldier of the First World War and the founder of Free France. Today, now that the last of the Great War veterans has passed from the scene, all victims of all wars are paid homage to by the relighting of the perpetual flame, so that memory never becomes extinguished.

On July 14, for the length of the Champs-Élysées, the republic gathers together to do honor to its soldiers and to the country they fought for. It is perhaps for that reason that some of France’s most significant achievements have been commemorated here. An endless sea of humanity for de Gaulle and the liberation of Paris in 1944; another to express attachment to the Général on May 30, 1968, when his government was in trouble; and another to celebrate the soccer player Zidane and the victory of the French national team in the World Cup of 1998. The occasions may change but not the setting.

But the Champs-Élysées, whose commemoration of war is framed by the Étoile and the roundabout, has plenty of other associations, and is now a place where politics and luxury goods merge. Sacha Guitry, the actor and playwright I mentioned earlier, made a film about walking up the Champs-Élysées. Let’s follow him.

* * *

Across the river from the Place de la Concorde is the Palais-Bourbon, now the home of the National Assembly; its twelve Corinthian columns were intended to reflect those of the Church of the Madeleine, as if in a distant mirror.

The palace was built in 1722 for Louise de Bourbon, the legitimate daughter of Louis XIV and the Marquise de Montespan. Nearly a half century later, the Prince de Condé enlarged the palace and gave it an appearance that was inspired by the Grand Trianon at Versailles.

In 1795, the Revolution took control of the palace, which, with its new semicircle approach, was henceforth home to the Council of the Five Hundred, as the new legislative assembly was called. The perchoir, meaning the stage on which the president of the Assembly sits, is a survivor of the revolutionary period, after which the Palais-Bourbon underwent a number of changes and modifications before becoming the home of the current deputies, who number 570 in total.

The northern neoclassical façade dates from Napoleon. Under the emperor, the newly established revolutionary institutions were subject to autocratic power. Reigning from the Tuileries Palace, whose gardens opened out to the Place de la Concorde, Napoleon refashioned Paris. To exalt the victories of the Grande Armée, he started construction on the Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, and to render homage to his soldiers he ordered built the Madeleine. Finally, to balance everything out, the Palais-Bourbon on the Left Bank was remodeled.

History often presents us with oddities. The building, which embodies the country’s republican institutions, carries the most royalist of all names. But it seems appropriate that before it was a symbol of the republic it was the favorite target of protests against monarchic power, in a time when democratic processes were subject to the will of a few.

* * *

In February 1934, on the Place de la Concorde, across from the Chambre des Députés, some thirty thousand people gathered together and threatened to launch an assault on the Palais-Bourbon; their goal was to bring down a government. “Against the thieves of this abject administration,” extreme right-wing militants—royalists, nationalists, and fascists—had mobilized themselves. Calling themselves variously the Action Française, the King’s Camelots, the Patriot Youth, and French Solidarity, they were open about their ambition to overturn la gueuse, meaning “the beggar,” which is what they called the republic and its left-wing leadership. The Croix de Feu, which was without doubt the largest of these organizations and mainly made up of World War I veterans, was angry at the government but had also no direct political affiliation. Under the orders of a lieutenant colonel named François de La Roque, they gave their speeches and then vacated Concorde, leaving room for the more violent right-wing elements to take over.

As night fell, thousands of protesters tried to march on the Palais-Bourbon, half as expression of public protest and half as attempted coup d’état. Very quickly the police were overwhelmed and fired on the crowd. Clashes continued throughout the night. Sixteen protesters and one policeman were killed; a thousand were wounded.

From his position as tribune of the Chambre, Maurice Thorez, general secretary of the Communist Party, galvanized his forces.

“I call upon all proletarians and upon all our brothers the Socialist workers to come out into the streets and to hunt down these fascist thugs!”

Three days later, on February 9, in the Place de la République, a Communist counterdemonstration took place and they too had lethal run-ins with the police. The result was six dead and sixty wounded.

Leaving behind the Place de la Concorde and moving up the Champs-Élysées, you will see on the right, slightly pushed back, an iron gate on which sits a golden rooster. This is the entrance to the gardens of the Élysée palace. Since the election of Prince Louis Napoleon to the presidency of the Second Republic in 1848, this former home of the Marquise de Pompadour, the pretty mistress of Louis XV, has been the French president’s official residence.

As noted earlier, Charles de Gaulle hated the place, which he thought too precious for a soldier like himself. Moreover, it was poorly designed; the food arrived cold into the dining room because the kitchen was too far away. And the idea of walking around the former palace of a royal mistress in slippers appalled the austere general.

How to get from the Revolution to the Concorde

In 1934, Concorde was sardonically referred to as “Place de la Discorde,” but it has had other names. In 1789, it was called Place de la Révolution, and the sinister silhouette of the guillotine rose up here. Here are the figures: 1,119 heads were severed in this spot, including those of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette. The statue of Louis XV, placed in the square in the mid-eighteenth century, was replaced by a plaster model of Liberté wearing her Phrygian hat. In 1795, after the Reign of Terror had ended, the government, keen to maintain civil order, mandated that it be called “Place de la Concorde.”

In 1800 the statue of Liberté was removed. A quarter of a century after that, Louis XVIII wanted to raise a monument to the memory of his brother, the guillotined king. As soon as the first stone was set in place, the square changed its name again and became Place Louis XVI. The work was interrupted by the Revolution of 1830. The square was then called Place de la Concorde once again, this time for good.

Still, if you look at the corner of the square where sits the Hôtel de Crillon, facing the embassy of the United States, you will see a plaque, dating from Louis XVIII, and on it you can still read “Place Louis XVI.” The king was beheaded several steps away, between the obelisk and the statue of the city of Brest.

In 1836, Louis Philippe had the obelisk, a gift to France by the viceroy of Egypt, Mehemet Ali, placed in the middle of the square.

Not all of de Gaulle’s successors have shared his opinion. Georges Pompidou, who was deeply interested in modern art, had the private rooms decorated with the luminous and changing colors of the Israeli artist Agam. But his wife, Claude, hated living in this cold place, which she called an “unhappy house” after the death of the president. She never went back there again, even to visit those who took up residence after she had left.

Valéry Giscard d’Estaing lived alone in the Élysée. His wife, Anne-Aymone, thought the private residence too small and poorly designed for her four children. This left the president with an open field. On October 2, 1974, when he was returning in the company of a pretty young actress, he rammed his Ferrari into the back of a milk truck. This of course caused great hilarity among journalists at the time.

For François Mitterrand, Élysée was a place of work. Torn between his “official” life on Rue de Bièvre with his wife, Danielle, and his other life with the mother of his illegitimate daughter, Mazarine, born six years before his election to the presidency, he never had much of a chance to live in the palace.

Jacques Chirac probably appreciated the place more than anyone else. In any case he made the residence quite sumptuous. “Chirac always lived where he worked and worked where he lived,” as one of his former associates put it. This was as true when he was the mayor of Paris as when he was president. Bernadette Chirac never attempted to hide her nostalgia for earlier times when she rearranged the palace’s flower garden.

Nicolas Sarkozy seemed to appreciate the splendor of the palace enough to marry Carla Bruni there on February 2, 2008. It was an intimate ceremony that took place in the presence of a few dozen people—close family and a handful of friends.

Sarkozy’s marriage was actually not the first to take place in the Élysée. On June 1, 1931, President Gaston Doumergue, who had remained a bachelor during his term, got married there as well, twelve days before his last day in office.

* * *

Continuing our way up this avenue, which is after all one of the world’s most beautiful, we should make a little side trip along the Avenue Montaigne to the Art Deco façade of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

In 1920, under the guidance of Jacques Hébertot, this playhouse represented the avant-garde: operas, ballet, plays, and concerts all took place there. The Swedish Ballet entranced Paris here, with music by Ravel, Debussy, Milhaud, and Satie. Here was where the twentieth century exploded onto the art scene.

Pablo Picasso designed sets. The Spanish-born painter had married Olga the Russian ballerina he had met in Rome and they had moved into a reassuringly bourgeois apartment at 23 Rue La Boétie, not far from the Champs-Élysées.

In 1905, fifteen years earlier, Picasso had decided to settle in Paris indefinitely, and could only afford a place in Montmartre—a ramshackle and off-kilter hovel dubbed the Bateau-Lavoir—the “washtub boat,” literally. For fifteen francs a month, he lived in a studio on the third floor on the courtyard.

One stormy night, a young woman hurried home, her clothes soaking wet. She had only just moved to La Butte—as Montmartre was called—and was starting a career as a painter and a model, posing for the most celebrated academic artists of the day. Fernande Olivier was her name, and she had noticed Picasso, a timid-seeming and broad-shouldered young Spaniard with burning eyes and jet-black hair that he was constantly brushing away from his forehead. They often crossed paths at the common sink near the entry, their buckets in their hands, sometimes exchanging a few polite words.

That night, Picasso ran into the soaking Fernande in the building’s narrow hallway. He was twenty-four, she a few months older. Full-bodied, even voluptuous, she looked charming in her trimmed hat out of which tumbled her blond hair; she was a little taller than he was. Picasso might have felt intimidated by this seductive woman were it not for his dark, devouring gaze. He stood in her way and, laughing, scooped up and offered her a little cat that was always hanging around. Fernande tried to get by him, somewhat coyly, but soon enough had accepted an invitation to visit his studio.

When Fernande entered into Picasso’s world for the first time, she was stunned by the agony that the paintings expressed. Happy bird that she was, living in the Butte, she couldn’t comprehend their despair and thought these unfinished works morbid. But what most struck her was the chaos of canvases, tubes of paint, and abandoned brushes scattered on the floor. To her horror, a tame white mouse lived in the table drawer.

Fernande gazed at all this strange artistic bric-a-brac and her laughing eyes and luminous face seemed to light up this sad den. Picasso fell in love. Before long pink tints, the color of happiness and hope, would find their way to his canvases.

In the spring of 1906, the Louvre organized a show of Iberian bronze sculptures from the fourth and fifth centuries that had been found in Andalusia. Picasso became obsessed with analyzing the forms and taking in the powerful expression of these statues. Several months later Picasso would make another seminal discovery. One evening in November, he had been invited to dinner at the home of Henri Matisse, the Fauvist painter, on the Quai Saint-Michel. Of course they talked about art. Matisse took a small statue that was sitting on some furniture and handed it to Picasso. It was a wooden figure of a black man, the first that the Spaniard had seen of the kind. He said nothing, but he wouldn’t let go of the statuette all evening long, his dark eyes analyzing the dark wood and his fingers gliding over the smooth surface. He felt what he had felt when he first saw those bronze figures in the Louvre.

The next morning, the floor of his studio in the Bateau-Lavoir was littered with pieces of paper, each one featuring a charcoal drawing of a woman’s face, sketched furiously and from various perspectives. Each face had one eye and a long nose that ended in a mouth.

Picasso fought with this painting for more than six months, producing innumerable sketches and drawings. The black statuette, the Iberian bronzes, the memory of Cézanne—they all seemed to be taking shape in a work that would be completely and utterly revolutionary.

In 1907, his friends gathered in the Bateau-Lavoir to view the outsized canvas that Picasso was calling The Demoiselles d’Avignon. The spectators looked at its twisted curves, its deformed aesthetic, its pink tints emerging from the darkness, and simply shook their heads. No one yet understood that the painting had brought art into the twentieth century. For now, the beginnings of the revolution were limited to the heights of Montmartre. Then it spread to the Théâtre Champs-Élysées, and from there out into the world.

Let’s return to the Champs-Élysées. Once through the Concorde traffic circle, the avenue shoots straight toward the Arc de Triomphe. On the left-hand side at number 25 is the former home of the Marquise de Païva, the Russian courtesan. Here is one of the rare vestiges of the Second Empire, a fashionable neighborhood in which the restaurants and leafy walks attracted an elegant crowd. At the turn of the twentieth century, descending the Champs—on horseback, in carriages, in hackney cabs, and then in the first automobiles—was deemed the height of luxury and distinction.

Whatever happened to the Bateau-Lavoir?

On May 12, 1970, at about two-thirty in the afternoon, the central Montmartre firehouse was besieged by phone calls. A fire had broken out in the Bateau-Lavoir.

By the time the smoke had cleared, the place was little more than a smoky ruin among which were calcified remains. The painter André Patureau, one of the residents, was stunned by how quickly it had all happened.

“It was horrible. I have lost everything. My paintings, my work, my whole life. I was working on a canvas in my studio on the ground floor when a thick black cloud of smoke poured into the room.”

Five years after the fire, the Bateau-Lavoir was reconstructed. The façade was left intact, as it had not been destroyed. Twenty-five working studios and elegant apartments replaced the old heap. Rue Ravignan, a door that is always locked, and an intercom system—these are what greet the visitor making his melancholy quest into the history of a place that once had been open to the four winds.

It is perhaps appropriate that this magnificent palace, completed in 1865, would today be devoted to the world of finance. Going farther up the Champs, someone out for a stroll would be assaulted by a confusion of signs and brands, same sporting feudal coats of arms. The statesmen and the artists have been replaced by businessmen. Today power resides neither in the Élysée nor in the Palais-Bourbon but in this line of storefronts, owned by the great conglomerates of luxury goods and those who pull the strings in the stock market. Seeking architectural souvenirs of the twentieth century we would choose the Art Nouveau façade of the Claridge, at numbers 74–76; that of the former Élysée palace, which became a bank, at number 103; or the Art Deco building, which, until just recently, housed the Virgin Megastore, at numbers 56–60.

Still, the construction of the RER, which has had a station under Étoile since 1970, has somewhat changed the Champs. For forty years, getting from the suburbs to here has been no big deal. The result is the avenue has lost something of its distinguished allure by giving in to chain clothing stores and fast food.

Yet they are still there—Lancel, Lacoste, Hugo Boss, Omega, Cartier, Guerlain, Montblanc. All of them light the sky on the Champs-Élysée, the triumphant procession of the new potentates.

In 2006, Louis Vuitton opened on the avenue, at number 101, and the reconfigured space became subject to all kinds of criticism, mostly because of the kooky window treatments. Yet whatever else you might say about these windows, on display were the original suitcases and bags, the most imitated in the world. And what is there to say about the new building for the drugstore called Publicis at number 133, a veritable institution now for more than half a century? Its transparent and curved design is typical of architecture of the end of the twentieth century and the new millennium. If nothing else, it leaves us perplexed.

Of all these new powers that be, the most obviously visible is the shocking new Versailles with its court, rising up in the distance ahead of you in La Défense, whose Grande Arche has become the Arc de Triomphe of modern times, a literal and figurative distant echo of Napoleonic glory.