The Statue of La Défense.

Twenty-first Century

La Defénse

Back to the Start

Going down into the terminus of Line 1 in the station at La Défense, you get a clear view of the Grande Arche, framed by the sidereal emptiness that its pretentious form imposes upon the eye. The twentieth century has not been kind to Paris, architecturally speaking: the Montparnasse Tower, the Forum des Halles, the Riverside Expressway (voies sur berges), the Centre Pompidou, the Bastille Opera, the François Mitterrand Library. The eyesores inflicted upon the capital are numerous and rather breathtaking. The Grande Arche came into being in 1989 and achieved the culmination of bad taste by being set within the sight lines of the Arc de Triomphe.

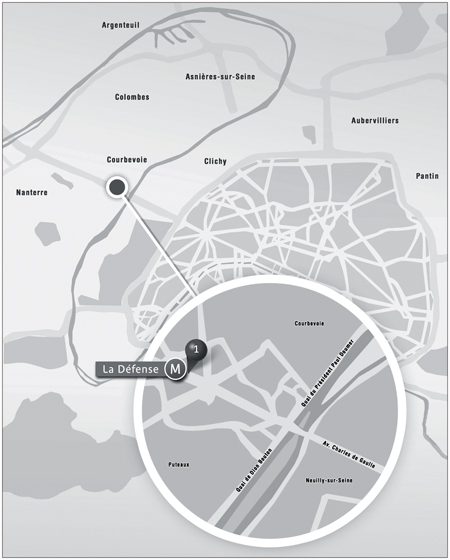

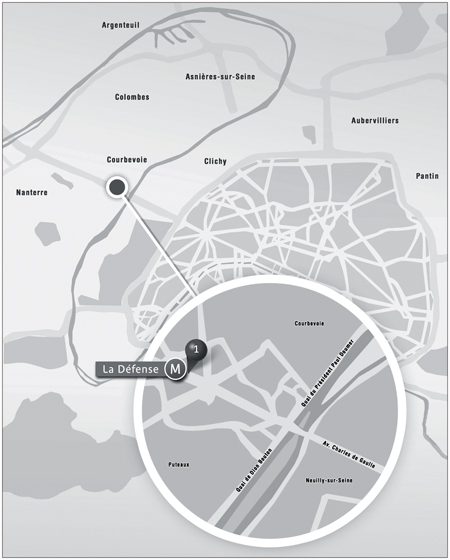

I’m being tough, I realize this. Who knows? Perhaps in a hundred years pilgrims will come to La Défense to pay homage to its elegance and power, just as Art Nouveau or Art Deco designs became revered architectural symbols for those living in the second half of the twentieth century. Perhaps they will gather here before this Arc de Triomphe of finance. The neighborhood of La Défense is barely fifty years old, after all. It was General de Gaulle who decided to start construction here in 1958, in the towns of Puteaux, Courbevoie, and Nanterre. He wished to create the economic and financial poles of the France of the Thirty Glories, as the years between 1945 and 1975 have been called. Looking toward the Arc de Triomphe, you will see at the far end of the square, a little lost in all the new construction, the statue of La Défense, erected in 1883 in honor of those who defended Paris against the Prussian invasion in 1870. It is to them that the quartier owes its name.

In my heart of hearts, rather than give in to a slightly absurd conservatism, I prefer to accept not the outrageous but the audacious architecture of my time. And then, as we know, time will do its work, history will judge—and better than I can, without question. Because in the end these are future remnants and vestiges, the remains of the century in which I live, and they are indispensable to Paris. Moreover, the magnificent museum on the Quai Branly designed by Jean Nouvel, near the Eiffel Tower, has already become a classic.

Now we can pose the following question: what heritage will the twenty-first century bequeath to future generations?

For the moment I believe these striking new superstructures, built with ephemeral and throwaway materials, will disappear fairly quickly. A number of archaeologists and architects worry openly about the short lives of modern buildings.

Whatever the case, the Paris of our century will be one of dizzying expansion. This will be the century of Greater Paris, a triumph of connective agglomeration that will overwhelm the périphérique and swallow up all or at least part of the suburbs and take along with it several districts in the process.

The axes that will need to be redrawn are already clearly visible: the Avenue Charles-de-Gaulle, which goes from Étoile to La Défense and runs through Neuilly like a freeway, will one day be refashioned. Projects are in the works. One day it will become a river of green whose current will end in the esplanade of La Défense, which by then will have lost its confused aspect, the product of haphazard or nonexistent planning.

And developing toward the west, Paris, the Greater Paris of tomorrow, will make this business district, with its thrusting office towers, a part of itself, a witness to its own past, a window open to its future. Then the capital will keep moving, extending farther west, and swallow up Nanterre, which is right behind La Défense.

Thus the city will slowly move back to where it began. As we might remember, the original Lutèce was located on the banks of the Seine in what is today Nanterre. The twenty-first century will perhaps see Paris return to this ancient home of the Gauls and discover again, more than two thousand years later, the bend in the river in whose nurturing confines it was born.