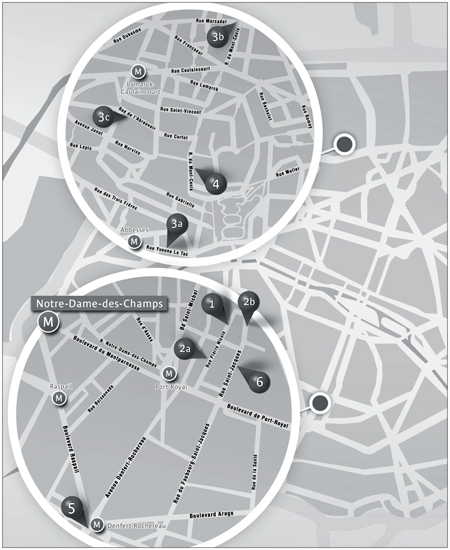

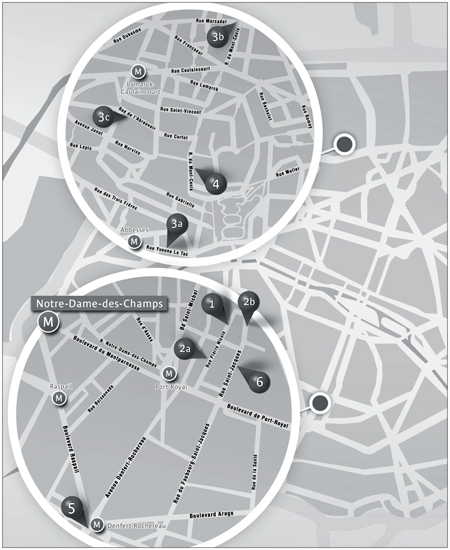

1. The Crypt of Saint Denis, the first cathedral in Paris. 2a–2b. The scattered remnants of Paris’s first cathedral. 3a–3c. The long walk of Saint Denis. 4. The church Saint-Pierre-de-Montmartre (2 Rue du Mont-Cenis). The four marble columns here are the last remnants of the Temple of Mercury. 5. The catacombs. 6. The catacombs were once officially called fief des tombes (“stronghold of graves”). An engraved inscription, FDT, on the stone wall at 163 bis Rue Saint-Jacques, serves as a reminder.

Third Century

Notre-Dame-des-Champs

The Martyrdom of Saint Denis

The escalator at the mouth of the Notre-Dame-des-Champs Métro stop disgorges subway voyagers right into the heart of Boulevard Raspail; pedestrians have no choice other than to disrupt the flow of traffic in an attempt to make it to the safety of the far sidewalk. I came here seeking a memory of ancient Lutetia, but nothing remains to evoke it. Straight in front of you, in a ramshackle little square, stands a statue of Captain Dreyfus, the Jewish military officer wrongly accused of espionage at the end of the nineteenth century. A little farther along, in Montparnasse, the church of Notre-Dame-des-Champs unfolds with its end-of-century rococo façade, a witness to the faith that animated the bourgeoisie of the Second Empire.

In these oddly shaped places away from the original center we enter into the domain of legend and mystique. Everything is hidden from those looking for obvious signs and dead certainties. To find what you seek you have to listen for the gentle breeze of credo and credulity.

By the middle of the third century, Lutetia had become an important center, important enough at least for Christians to dream of coming to convert the population. For this was a place of worship of Toutatis and Jupiter, Gallic gods and Roman gods sharing the same altars.

Meanwhile, in Italy, an energetic bishop named Dionysius burned with an inextinguishable fire for Christ and wanted to spread the True Faith, to extend the religion of the crucified God and to save those souls lost to paganism. He humbly placed himself at the feet of the bishop of Rome, the successor to Saint Peter, and implored of him a mission of catechization. The bishop had other things to preoccupy his thoughts, such as ensuring the survival of Christianity in the face of persecution. Spreading the Good Word was put off for better times. He thought he had gotten rid of this irritating neophyte by sending him on a mission to convert the Gauls, and good luck to him! It was well known that Gauls were resistant to all change and clung obstinately to their old idols. Their reputation did not deter Dionysius, who was happily willing to face any difficulties and if necessary to level mountaintops to help Christ the King triumph.

With two companions, the priest Rusticus and the deacon Eleutherius, Dionysius, now known as Denis, made his way to Lutetia in about A.D. 250. The three men made their way into the city by way of the cardo maximus and walked straight to the forum. They were appalled by what they found: a population given over to pleasures and to false idols. Everything disgusted the ascetic Christians: shops devoted to women’s vanity and sacrifices made to stone statues. Those who dreamed of a just and beneficent God whose benevolent gaze could overturn the despair of the human soul simply could not understand how one could worship these vulgar superstitions.

So they put some distance between themselves and the town and sought refuge in the surrounding vineyards that stretched into the distance, there to practice and to teach this new religion. Eventually, Denis’s devotion attracted small crowds who were willing to be converted. But danger was close behind; even here, Christians were persecuted. To protect themselves, they continued to evangelize but now in the secrecy of an abandoned quarry, or in an underground passageway from which the stone that went into the construction of Lutetia had been dug. The Christians held their ceremonies in secrecy, and the clandestine nature of it deepened fervency and suspicion.

What happened to Paris’s first cathedral?

Given that Saint Denis was the first bishop of Paris, the secret church in which he catechized was indeed the city’s first cathedral. To find the spot when you come out of the Métro, you have to walk up Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs, for the key to the enigma can be found at the end. After having crossed Boulevard Saint-Michel, you find yourself on Rue Pierre-Nicole, a small and straight path that seems somehow sleepily provincial. Pushed up against the brick walls of a high school is an enormous structure of wood and flagstones of the type that tended to flourish in modernist architecture of the 1960s.

Impassive, the building’s doorman refuses access to this wandering historian. This is private property, he explains. To gain access and to seek the trail of Denis will take persistence. Which paid off. Thanks to one of the building’s co-owners I was able to visit the basement.

An elevator, a parking garage in which cars are neatly tucked into evenly spaced spaces marked with white paint, and then suddenly there was a partially concealed door. Once through, we’ve entered the past, a dark stairway taking us down by degrees into the depths of an ancient quarry. Descending gives the impression of going deeper into time. The vaults were stabilized and restored in the nineteenth century, but you can still find more ancient vestiges. Beneath a tombstone sleeps Saint Reginald, who died in 1220. It is said that a vision of the Virgin launched him on his priestly career. The long nave reaches the altar, on which sits the statue of Saint Denis. The centuries of devotion have consecrated the place where he once preached.

Guides for tourists from a century ago still mention the crypt. Later it was swallowed up in the foundations of the building that rose up above it. All that remains of Paris’s first cathedral lies buried under this parking garage, partly integrated into the management company that maintains it but which also reserves it only for a select few. It is an absurd situation: the only vestige of the first Christian Parisians has survived because of the good faith of a few private citizens. And yet the history of this place is so rich.

The secret cathedral was replaced by an oratory in the seventh century, and by a church a hundred years following that, and then by a priory that was built in the twelfth century. Finally, at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the Carmelites of Notre-Dame-des-Champs took over the place. The Revolution ravaged the convent—as it did so many places of worship—but the tomb of Saint-Denis, hidden in the depths, escaped destruction. In 1802, when the sisters rebought the parcel of land above the tomb and built a more conventional space. These buildings were demolished when the convent closed definitively in 1908.

From this long stretch of history, a few scattered remnants are still visible today:

• The stone frame of one of the convent’s entrances that was conserved but integrated into a store that was built on the ground floor of the modern building at 284 Rue Saint-Jacques.

• A small oratory enclosed in the private gardens of 37 Rue Pierre-Nicole.

• And of course, the tomb located beneath the parking garage of 14a Rue Pierre-Nicole, along with several fragments of the convent walls brought up during the new construction.

The first furtive mass they held was sung in one of their hidden sanctuaries, and the name given it by tradition was “Notre-Dame-des-Champs”—Our Lady of the Fields—though actually rather than “fields,” it should have been called “depths”—Notre-Dame-des-Profondeurs. Here in this improbable location the first believers affirmed their faith. Out of the darkness of this cave, which eventually became a cathedral, grew Paris’s Christian future.

Trembling as they huddled around Denis were Gallic and Roman families determined to be baptized, whatever the risks. Enveloped in a darkness broken only by the flickering flames of the small oil lamps, Denis spoke. Wearing his white robes, his eyes flashing in the dim light, he spoke movingly about Jerusalem and Golgotha. And the great cross of dark wood barely visible in the shadows lent dramatic and tangible authority to what he was telling them.

To locate the spirit of Paris’s first Christians, a better option is to visit the catacombs, whose entrance can be found on Place Denfert-Rochereau. Here you can enter into a vast necropolis, the largest in all of Paris, just as Saint Denis once did.

During his time, the necropolis was located beneath the cardo maximus, in spaces hollowed out by the ancient quarries. This was one of those lost places, ideal for Saint Denis and the other Christians for whom death was but a passage into the Kingdom of God before the Resurrection. The flesh inhabited the realm of shadows: “catacomb” comes from the Latin cumbere, “to rest.” This place, which was called “fiefdom of the tombs,” has left an enduring memory: we are reminded of it by the inscription FDT (fief des tombes) at 163a Rue Saint-Jacques.

The Denfert-Rochereau necropolis that one can now visit was created as late as 1785, and for sanitary reasons. It was located on the city’s outskirts and designed to receive bones from the city’s churches. The remains of six million people were transported there, including those of Fouquet, Robespierre, Mansart, Marat, Rabelais, Lully, Perrault, Danton, Pascal, Montesquieu, and so many others of note.

But we need to go back. The path that led us to the entrance of the ossuary is that of the foundation of an ancient Roman aqueduct that carried water from Arcueil. Following this path takes us back to the Roman period and to Saint Denis, praying in secrecy and in darkness.

One day in the year 257, Roman legionaries made their way into his underground church. They had come to arrest Denis, Rusticus, and Eleutherius. To the Romans these were troublemakers all. Having repeated the claim that the stone idols were not the true powers in the universe, these rebels had shaken the spirits of even the strongest souls. Were they allowed to continue to preach, the entire social order was at risk. The three men were forthwith led before the prefect Sisinnius Fesceninus, the Emperor Valerian’s representative in Lutetia. Like his superior in Rome, the prefect could not abide the disorder that the Christians represented.

In the time of paganism, the emperor was the object of veneration and those who did not adhere to this imperial faith were persecuted, including but not limited to the Christians. For Christians, it was a matter of rendering unto Caesar what was Caesar’s and unto God what was God’s. They were not much concerned by the temporal; it was the heavenly that preoccupied them. In any case, Christians were not good subjects of the emperor and their loyalty was always in doubt, which was even more dangerous to the social order; they rejected the official religion and recognized only Jesus as the son of God.

Where did Saint Denis’s long walk lead him?

The hill on which Saint Denis was beheaded took the name Mont-des-Martyrs—Hill of Martyrs—which eventually became shortened to “Montmartre.” The hill had already been sacred for quite some time. A temple dedicated to Mercury was almost certainly built there by the Romans. In 1133, Louis VI acquired the hill and founded a Benedictine abbey there. The abbey was ransacked during the Revolution and the last mother superior, elderly, deaf, and blind, was accused of having plotted “deafly and blindly against the Republic.”

Today the white pastry dome of Sacré-Coeur recalls Montmartre’s religious past. The building’s foundation stone was set in place in 1875 and it is said that the dome was built to “expiate the crimes of the Commune” (about which more later in the chronology). That’s actually not the case. The decision to restore Montmartre to its religious past had already been made a few years earlier, during the reign of Napoleon III.

As for Saint Denis, headless, he would have left the hilltop of Montmartre by means of Rue du Mont-Cenis. He would then have doubled back along Rue de l’Abreuvoir to wash his head in the fountain in Place de Girardon, where a statue commemorates the occasion. Then he would have gotten back on Rue Mont-Cenis along which if you walk you can see at number 63, at the corner of Rue Maradet, the turret of a house that dates from the fifteenth century, the oldest construction in Montmartre. The turret offers a modicum more authenticity than Place du Tertre, which looks like it came out of Disneyland.

Saint Denis thus walked about ten miles holding his head in his hands. The place where he was buried is today Saint-Denis Basilica.

Around his tomb, which visitors can still admire in the cathedral’s crypt, a mausoleum was built. In the seventh century, King Dagobert decided to found a monastery and to make the martyr’s mausoleum into a final resting place for himself and his family. Thus Saint-Denis became the necropolis for the kings of France.

Prefect Fesceninus was ready to make an example of these men, but equally prepared to be magnanimous in the event of repentance. He therefore offered the prisoners a choice: submission to the emperor or death.

“No man can force me to submit to the emperor, for it is Christ who rules,” replied Denis.

He was speaking in a language with which Fesceninus was unfamiliar. The best that the prefect could do was to stop the man’s ravings. To teach him to think in a more righteous manner the prefect ordered Denis’s head to be separated from his body.

In their prison, awaiting the execution of their sentence, Denis and his two codisciples continued, despite the circumstances, to preach the great mystery of the Redemption of Humanity and together celebrated one final mass.

Soon the three men were taken from their cell and dragged to the top of the highest hill in Lutetia, from which their fate could be observed by one and all. A cross was raised on which Denis was tied and his head cut off. Then, a miracle! The lifeless body was transfigured by the apparition of the Savior. Headless, it came to life, undid the bonds that held it, and started to walk. Denis picked up his own head and carried it over to a fountain, where he washed it off, and then made his way back down the hill. He walked for about ten miles until, finally, he confided his severed head to a good Roman woman named Catulla. He then collapsed in a heap. Catulla respectfully buried the pious man in the very spot where he had expired. And on this spot instantly grew a single blade of white wheat, a final miracle.

What remains of Denis the martyr in Lutetia? The miracle was probably not even noticed. Heads were being removed at so rapid a clip at the time that no one paid much attention.

The Lutetians had other troubles. The city had enjoyed peace and prosperity for more than a century and now was about to lose them.

Nothing in Imperial Rome was working any longer. This had been happening for some time. One emperor was replaced by another and their followers tore at each other’s throats; authority passed to whoever survived. It was an age of backroom deals, plots, and treason. Valerian fought in Mesopotamia but was defeated and taken prisoner by the Persians. No one mourned his loss. Romans didn’t want this disgraced emperor to return and hence didn’t engage in negotiations. The captive rotted in his Persian dungeon and when he finally died in captivity it was to the great relief of one and all. This worked out nicely for his son and coemperor, Gallienus, who became the sole legitimate emperor.

In short, Rome was Rome no more. The emperor was no longer a man far above other men, feared and worshipped both. He had become a subject for plots, enmeshed in corruption and petty dealing. The degradation of political tradition and leadership proved a disaster for the enormous empire, which required stability in order to survive. Into this void came chaos. The empire was unraveling and the barbarians were at the gates. They could sense what was happening: the Romans were weak; the time had come to overwhelm them. The German tribes crossed the Rhine and invaded Gaul, turning it into a site of savagery and rape. The enemies pillaged the countryside and took back with them all of its richest spoils.

Marcus Cassianus Latinius Postumus was a brilliant Roman general of Gallic ancestry. Sometime around the year 260, when the German tribes attacked Roman Gaul, Emperor Gallienus and Postumus prepared to repel them. Each one wanted to go after a different enemy. The emperor was determined to chase the Alamans back to the east, and the general to push the Franks back north.

Postumus fought so valiantly that his stature among his troops skyrocketed: the legionaries were prepared to proclaim their general the next emperor. But emperor of what, exactly? Of Rome? Of Gaul? Gallienus, who sensed that his dynasty was in trouble, gave his son Saloninus the title of Augustus: he, and no one else, would succeed his father. Thus they hoped to moderate the ambitions of the Gallic general.

But these were hard times for the son of an emperor. Postumus could not abide the thought that one day Roman authority would be assumed by this dullard Saloninus and attacked Cologne, capturing Augustus Saloninus and promptly executing him. All that remained for him to do was assume the imperial symbols. His soldiers pronounced him emperor of Gaul. His image became familiar to one and all—his handsome visage, full beard, and golden crown were set on the coins minted to regulate the economy of his new domain.

As far as Rome was concerned, Postumus was nothing but a usurper, of course, but one whose ambitions, happily, seemed rather limited. He apparently did not have in mind toppling the Roman emperor, nor crossing the Rubicon, nor trying to make himself legitimate in the eyes of the Senate, and did not seem to call into question his “Romanness.”

He did finally want to rule, even though he avoided assuming the supreme title and preferred to refer to himself more modestly as “Restorer of the Gauls.” Still, by unifying the Gauls under his power he was effectively separating them from the Romans. For the first time in a long while, Gaul and Rome were separate political entities, no longer responding to the same authority.

As for Gallienus, while such insubordination galled him, the Alamans were just then giving him all that he could handle; the German tribe was attempting to cross the borders, which needed constant supervision. So a kind of tacit agreement rose up between the emperor of Rome and the Restorer of the Gauls, one from which each gained something: Postumus was in charge of defending the Rhine and in exchange was given control of Brittany, Spain, and a major part of Gaul.

Things eventually ended badly for Postumus. Having overcome so many obstacles on his rise to power he ended up being killed by his own soldiers. In 268, when the town of Mogontiacum revolted against his authority, Postumus tried to bring the seditious town under control and put the leaders of the mutiny to death. This justice, though expedited, was not enough for the Gallic troops, who wanted to pillage the city. What was the point of going to war, after all, if you couldn’t gain something from doing so.

Postumus refused to let them. He was not willing to see a town in his empire pillaged, particularly a town as valuable as Mogontiacum, which was critical to the defense of the Rhine. The boorish soldiers would have none of this line of reasoning; they wanted to enrich themselves and nothing else would satisfy them. The Restorer of the Gauls stood in their way; he would simply have to be brought down. Postumus and his son and his personal guards were all massacred. Thus, Postumus passed from this life. He had reigned over the Gauls for ten years, succeeded in pushing back the invaders, and brought to the region financial prosperity.

These events, which had repercussions from Brittany all the way down to Spain, shook Lutetia profoundly. Tension was palpable on the banks of the Seine. Hordes of German barbarians wearing helmets and carrying hatchets were roaming the countryside, destroying the harvest and pillaging. Out of caution these tribes left Lutetia alone. On the other hand, the part of Lutetia that extended onto the Left Bank was beyond the city gates; it was wealthy, vulnerable, and ripe for the taking. Hordes suddenly descended upon it and then disappeared just as quickly.

When the Germanic tribes had moved off, they left the field to bagaudes, armed brigands (from the Celtic term bagad, meaning “band”). These bands, comprised of thieves, deserters from various armies, and dispossessed peasants, avoided attacking the Roman legions and let the cities be, but they spread terror throughout the countryside.

The hills were no longer merely home to wild beasts and spirits. A ragtag army lived in the crevices. Surviving on the remains of the empire, these bandits ravaged villages and rural dwellings, massacring and raping, carrying off anything of value. Thus sometimes could be seen on these distant paths cohorts comprised of bloodthirsty men, loaded down with golden cups and various weapons, carrying jars filled with the finest wines, pushing before them fattened sheep and cattle and dragging behind them terrified women with bound hands who stifled their tears so as not to awaken the cruelty of their new masters.

Between the double threat of barbarians and bagaudes, the Roman aristocracy abandoned Lutetia sometime around 270. The elegant and prosperous city that had stretched along the Left Bank was deserted. The cardo maximus on which beautiful Roman women had paraded became rutted and potholed, the houses that lined the road were abandoned and fell into ruin. A bit lower down, the forum—in which only shortly before the flames of sacrifices made to the gods had burned, the forum where merchants sold rich jewels and sweet-smelling ointments—was nothing but an empty shell.

* * *

Against every expectation, the empire of Gaul did not collapse with the death of its “restorer.” A successor rose up, replaced the slain leader, and assured continuity: Tetricus, a Roman senator born to a Romanized Gallic aristocratic family, seized the reins of power. Unlike his predecessor he was not a military man but a “politician.” Tetricus knew that Gaul would one day soon again fall under the sole authority of Rome. The empire of Gaul was condemned to rejoin the Roman escutcheon. His job was essentially limited to that of preserving Gaul at a moment when it was being attacked along several fronts, and while the regime on the Tiber River was showing real signs of weakness.

And indeed, in 273, the emperor Aurelian undertook the reconquering of lost provinces. Near Châlons-en-Champagne, Tetricus and his troops capitulated without great resistance. Aurelian celebrated his triumph with great pomp. At last the empire was reunited. Meat was roasted and prisoners from all the barbarian nations were paraded in the streets. Tetricus was led through the streets of Rome. The Gaul was the silent living symbol of the all-powerful Aurelian, the emperor who had turned into the “restorer of the Roman world.”

After his unrivaled triumph, the victorious emperor quickly pardoned Tetricus, and the former chief of Gaul was not only not treated as a defeated enemy but named governor of Lucania in the south of Italy, and given back his place in the senate.

* * *

Meanwhile the barbarians continued to threaten Lutetia, which was reduced once again to the Île de la Cité. It was decided that the city, already protected by the river, would be safer still were it surrounded by a fortified wall. All the materials necessary to construct it were at hand. Houses, monuments, and even tombs were despoiled of their ornaments and stones, which were integrated into the ramparts that encircled the island, absorbed the port, and swallowed up the riverbanks.

Henceforth, posted at the extremities of the Cité, guards watched the river. At the slightest suspicious movement the alert was sounded. Lutetia was prepared to defend itself. It seemed impregnable. With access to the water, the woods, and the fields, it would be able to gather together everything necessary to survive a long siege. An army was formed to inhabit the city, and a flotilla sat ready in the river harbor. Lutetia had become an integral part of the defense system of northern Gaul.

By reason of its own precariousness and location, the settlement became a stronghold. However, now deprived of its Left Bank expanses, it no longer had the resources to match the greatness of other places in the empire. Its population was reduced to a bare minimum; its most beautiful edifices were gone. Compared to Poitiers, for example, it paled.

Lutetia, once a great Gallo-Roman city, had become the Gallic city that henceforth would be called Paris, from the name of the Civitas Parisiorum that alone survived within its fortified walls. Paris did not, alas, possess the architectural elegance of Lutetia. It was but a small town hunkered down defensively on an island in the middle of a river, trembling in expectation of fresh attacks from the German tribes massing in the north and in the east.