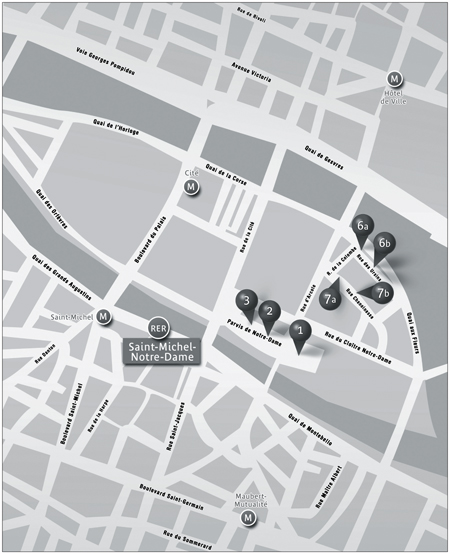

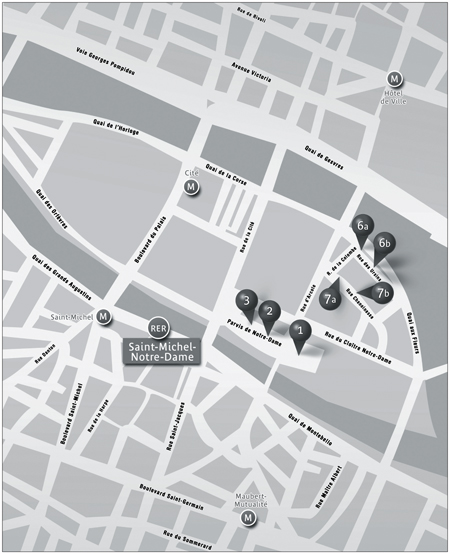

1. Notre-Dame—the secret of Biscornet. 2. Notre-Dame—ground zero of all the roads of France. 3. One can find traces of the original square in front of Notre-Dame (six times smaller than it is today), before Haussmann expanded it in 1865. 6a–6b. The best way of imagining the Île de la Cité as it once was is to stand on Rue de la Colombe, kitty-corner from Rue des Ursins. At number 19 Rue des Ursins is the Saint-Aignan chapel, which is the last of the twenty-three churches that once surrounded Notre-Dame. 7a. 18 and 20 Rue Chanoinesse, the barber and the pastry chef. 7b. At 22 and 24 Rue Chanoinesse, beautiful houses dating from the sixteenth century.

Sixth Century

Saint-Michel-Notre-Dame

The Merovingians, Elder Sons of the Church

Notre-Dame—the cathedral, the novel by Victor Hugo, and also, since 1988, the utterly charmless train station through whose passages people hurry to find fresh air—opens out into the wide expanse of the cathedral square.

That square today is six times larger than it was in the past. To get a sense of how it has changed, look at the markings on the ground: they reveal the winding trail of the old streets that surrounded the cathedral before 1865, when Baron Haussmann gave it the appearance that we know today.

Notre-Dame square is the ground zero of all of the roads of France. This is partly because it was the site of an ancient wooden post known as the bishop of Paris’s Ladder of Justice. At the foot of this ladder the accused were brought to make amends before the sentence upon them was carried out. They approached in their shifts, a rope around their neck, a candle in their hand, bearing on their chest and back a sandwich board detailing their crime; they kneeled before the Ladder of Justice and publicly admitted to their crime and pleaded for forgiveness for their sins.

Walking in the neighborhood around Notre-Dame, one can find a number of rather moving vestiges of what was there before. The best way of imagining the Île de la Cité as it once was is to stand on Rue de la Colombe, kitty-corner from Rue des Ursins. At number 19 Rue des Ursins is the Saint-Aignan chapel, which remains the last of the some twenty-three churches that once surrounded Notre-Dame. Then, moving in the direction of Rue Chanoinesse, at numbers 18 and 20 once stood two houses, one occupied by a barber and the other by a pastry chef. The barber cut the throats of students living in the dormitories of Notre-Dame and delivered their bodies to the pastry chef, who made pâté out of them, which in turn was then delivered to feed those living in the dormitories. These two accomplices were burned alive in 1387. In the garage of the motorcycle policemen who live in these locations today you will find another part of the Gallo-Roman rampart, dating from the fourth century: an odd projection of stone that has survived the centuries under the name Butcher’s Stone, for it was there that the pastry chef received his sinister ingredients. At numbers 22 and 24 the quite beautiful houses that were once students’ living quarters, dating from the sixteenth century, are still visible. If you make your way into number 26 you will see tombstones, which for several centuries have served as flagstones to keep feet dry in the event of floods. But this older Paris is more and more hidden, and the digital codes guarding the doors make it less and less accessible.

What Notre-Dame’s square inspired

At the beginning of the 1970s, having in mind the construction of a National Center for Art and Culture on the Right Bank, President Georges Pompidou wanted the center to open onto an esplanade that would evoke the one in front of Notre-Dame Cathedral. By so doing he was emphasizing the sacred nature of art, and his multidisciplinary home for it—the Centre Pompidou—would become a cathedral open to all forms of devotion.

To find the heart of Frankish Paris, you have to go back through the centuries, back to the death of Clovis in 511.

When this Christian king died, the country was divided up between his four sons: Thierry inherited the eastern part; Clodomir, the region of the Loire; Clotaire, the northern part; and lastly, Childebert, who got Picardy, Normandy, Brittany, and especially the Île-de-France, with Paris, already a populous city of twenty thousand citizens.

The chronology that followed was somewhat complicated and sometimes confused. The sons of Clovis spent their time strangling their nephews, out of fear that they might claim a part of the succession; making war to enlarge their inheritances; and attempting to make peace with one another, under the insistent pressure from the good-hearted Clotilda, the grieving widow of the Frank king.

Then, because someone needed to be king, they would bump off neighboring monarchies with the intention of enlarging their inherited kingdoms. Hence Childebert and his brother Clodomir declared war on Sigismond, the king of the Burgundians—or more exactly the Burgundies, as they were then called. They laid siege to Autun, but on the field of battle Clodomir was recognized because of his long hair and the Burgundians cut off his head and stuck it on the tip of a pike. This incensed the Franks and spurred them on to victory. The triumph was celebrated by an all-out massacre of the defeated soldiers. Sigismond, his wife, and his children received a very particular kind of justice: they were thrown into a well.

The death of Clodomir worried his brothers. They feared that the dead man’s sons would demand their part of the inheritance. Queen Clotilda wanted to avoid a family feud, and thought that she could prevent the worst by placing her three grandsons under her protection. Childebert brought his brother Clotaire to Paris and there dark plots were hatched in the palace of the Cité.

To ease people’s alarm, Childebert and Clotaire spoke in reassuring tones. This meeting was nothing more than two kings gathering to help Clodomir’s children inherit the throne of their father. Kindly Clotilda seemed relieved by this and leaned over her grandsons in a grandmotherly way and said, “I will no longer believe that I lost my son Clodomir if I can see you inherit his realm.”

This turned out to be a false hope, for assassins were watching them. The Cité palace became the site of almost incredible violence. Clotaire seized the oldest son and without hesitating stabbed the boy in the throat. Horrified, the next oldest son threw himself at the feet of Childebert and cried out, “Help me, O pious Uncle! Keep me from perishing like my brother!”

Where did Saint-Cloud get its name?

Clodoald, Clodomir’s third and youngest son, succeeded in avoiding his brothers’ fates thanks to help from a few officers who took pity on him. The child had seen close up the horror of power and decided to cut off his long hair, a mark of his royalty, renounce the world, and devote himself to the adoration of God. He moved to a fishing village on the banks of the Seine, where he built a monastery. Clodoald today is better known by the name Saint Cloud, and the village that took him in perpetuates his name.

Childebert hesitated. Was it really necessary to eliminate the entire household of the dead Clodomir? He turned to Clotaire.

“Please, sweet brother, show your generosity and spare the life of this boy.”

This was strange. Spare the life of a child who could one day turn against his family? This was unthinkable. The entire race of Clodomir had to be wiped out.

“Give up!” roared Clotaire. “If you don’t, you’ll die in his place!”

Childebert was stunned by his brother’s rage, and let the boy go. Clotaire immediately plunged his dagger into the boy and then finished his young victim off by slowly strangling him.

After the murder of Clodomir’s two sons, Théodebert, Thierry’s son, convinced now that his uncles were plotting his assassination, allied himself with Childebert to vanquish Clotaire. Alliances shifted. The two armed families were in full force, but the elderly Clotilda was still hanging around in an attempt to reconcile her descendants and to prevent future homicidal acts. She prayed so hard that a terrible storm broke over the field of battle. The combatants were impressed by the fury of the skies whose purpose was clearly intended to keep them apart. Perhaps they didn’t really want to tear each other apart in the muck. The brothers and the nephews ceased hostilities and fell into each other’s arms.

Still, the troops were so well armed and so ready to fight that it would have been a shame to waste them. They decided to march on Spain, where the Visigoths lived. Surely there would be a village or two to seize.

After occupying Pamplona, Childebert and Clotaire, the reconciled brothers, headed off to Saragossa, but the village resisted and the Frankish army was decimated. For Childebert, the moment had come to break camp and head back for Paris.

But, in this year of 542, the king did not return to his capital with his tail between his legs. From this militarily fruitless expedition he brought back two precious relics: a golden cross and a tunic that had once belonged to Saint Vincent, a Spanish martyr from the third century who has tortured to death during anti-Christian persecutions under the emperor Diocletian. Though a barbarian king and cruel by nature, Childebert nonetheless evinced a great respect for religion and vowed eternal friendship with the good abbot Germain, his counselor and protector of the poor.

Childebert never forgot the active role that the Church and Rome played in the growth and development of the Frankish realm. With the dissolution of the empire, the Church and its bishops had come to form Gaul’s administrative and social infrastructure. The Franks relied upon its workings. Turning themselves into Christians was no big deal. Paris was worth saying a mass for.

Moreover, the order and organization of the Church had immediately appealed to the extremely disciplined Frankish tribes, who were less exalted than the other invaders, and who had been taken over by Arianism, an Eastern and heretical form of Christianity closer than not to the Platonic philosophy, against which Rome strongly fought.

In short, by general agreement, Rome was put in the hands of the Franks and Frankish Gaul became the elder daughter of the Church, benefiting from its influence over its people. This new Gaul was built upon religious fervor.

* * *

“Childebert, you must build an abbey in which to house the relics you have brought back from Saragossa,” declared Abbot Germain.

Naturally, the abbey would be run by Germain himself, the first rung up the ladder that would transform this humble cleric first into a powerful bishop and later into a venerated saint. Slowly, the abbey-reliquary rose up outside the walls of Paris.

At the same time, the king interceded with the pope to get Germain ordained bishop of Paris. The good abbot, a modest and contrite man, tried to dissuade the king and pope from this. His life of contemplation and his love of the poor and the unqualified wisdom he could give to the mighty and powerful were enough to confer earthly happiness. But then the Holy Spirit visited him in a dream and revealed to him that the holy powers demanded of him—demanded!—that he accept the office. So he did, and was promoted to the head of the Parisian Church.

The Merovingian king, who still regarded himself as the secular arm of the Church, wanted his new prelate to have a cathedral worthy of the capital. To prove his devotion and submission, Childebert took charge of building a splendid edifice inspired by Saint Peter’s in Rome.

* * *

On the easternmost point of Île de la Cité in Roman days stood a monument to Jupiter, the vestiges of which are kept today in the Musée de Cluny. Given the triumph of Christianity, it was right and good that the dilapidated old temple be replaced by the most beautiful of sanctuaries. Christian peace had replaced the Pax Romana, and thus the new structure would be, appropriately, built upon the ancient Roman ramparts. This new use for old walls would be the visible and tangible symbol of how Roman military might had been supplanted by an even more powerful spiritual power.

This was how the Saint-Étienne Basilica came into being. It was an impressive monument: five naves, 230 feet long and nearly 120 feet wide. It was the largest church in the realm. Those interested can find the drawings for it on informational signs in Notre-Dame’s square. The foundations of the southern wall, built upon the Roman walls, can be found in the archaeological crypt.

In those days a cathedral was not an isolated edifice. Quite the opposite: it was the center of it all. A cathedral represented the meeting point of a number places of worship. Hence a baptistery was attached to Saint-Étienne, situated, logically enough, beneath the shrine to Saint John the Baptist, as well as a church already called Notre-Dame. This impressive cluster of ecclesiastical structures constituted Bishop Germain’s new seat, his cathedra. If you believe the word of his followers, the prelate never stopped digging into the royal treasury to perform deeds of charity. He even took bread from the mouths of his monks and gave it to the poor. The brothers were furious but didn’t dare confront a saint who was, after all, capable of performing miracles; it was said that Germain healed the sick and infirm, exorcised demons, and even raised the dead.

How did it come to pass that Notre-Dame replaced Saint-Étienne?

In 1160, Maurice de Sully, the bishop of Paris, decided to build a cathedral, one which would be even grander than Saint-Étienne and the older Notre-Dame combined. Saint-Étienne was as we’ve seen 230 feet in length; the new structure would be almost 400.

This was a gigantic project and took 107 years to complete, hence the expression (in French at least) “waiting a hundred and seven years” (and the printed page on which this sentence appears in the French edition of this book was, well, 107. Nice coincidence, don’t you think?). It is said that a Parisian craftsman named Biscornet was put in charge of installing the panels on the iron doors as well as the locks. Faced with such a daunting task, he called upon the devil, and the Malevolent One gave him such effective assistance that it required holy water to make the keys work. But the metalwork was so particular that even today, it would seem, experts cannot explain how it could have been accomplished. Unfortunately, Biscornet died soon after completing his task and took his secrets with him to the grave.

Across the centuries, the cathedral was continuously worked on, and it’s only by sheer luck that it still stands today, given all the events that threatened its survival. Condemned to be torn down during Revolution, it managed to escape. A little later, Napoleon’s coronation took place in Notre-Dame, but it was necessary to hang tapestries in order to conceal the deplorable state of the walls.

In 1831, with his novel The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Victor Hugo awakened the conscience of the government and of public opinion. From that point on, the whole world was in agreement that the cathedral must be saved. The architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, who specialized in reconstruction, was put in charge of the restoration. The work would take nearly twenty years and, for good or for ill, would involve an attempt to restore the cathedral to the way it looked in the Middle Ages.

In particular it was necessary to rebuild the Gallery of the Kings, which extends along the façade beneath the three main doors. Originally this consisted of twenty-eight statues of the kings of Judah and Israel, representing the traditional ancestors of Christ. During the Revolution, they were believed to resemble the kings of France and hacked to bits with iron bars. Viollet-le-Duc put his own statues into the empty niches in order to give the wall its original appearance. In 1977 came some welcome news: a few pieces of the ancient figures had survived destruction and were found during construction along Rue de la Chausée-d’Antin. They are on display in the Musée de Cluny.

September 13, 558, stands as a great moment for Paris, its populace, and its clergy, for that was the day on which the church Saint-Vincent-Saint-Croix, located on the Left Bank, was completed, following more than ten years of construction. Everything was prepared for this monumental event, for which the elite of the Catholic hierarchy and the cream of the nobility would all gather. Childebert was expected and, indeed, this would be his hour of glory, during which, all at the same time, his military campaigns, his religious loyalty, and his successful governance of the realm would be celebrated. Germain was there as well, surrounded by six other bishops recruited for the occasion.

They awaited the arrival of the king. And they waited some more. No king. The king couldn’t come because, as it turned out, the king was dead. Suddenly and without warning, he had chosen the moment of his triumph in his city to give up the ghost. A sad fate, and yet also one conferring glory.

The question was, what to do? Germain was unsure, as were the prelates. Should they postpone the ceremony and throw themselves into grief? Germain revealed his gift for using symbols and his mastery of communications by deciding to proceed with the ceremony, and then, that very day, to conduct the royal funeral. He would do both.

With a red cape draped over his shoulders, surrounded by his priests and disciples, Germain daubed holy oil on the basilica’s twelve pillars, representing Christ’s twelve apostles, and then he poured the liquid onto the altar, the church’s sacred core, the meeting place between heaven and earth.

In a strong and steady voice, the bishop recalled the prophesy of Saint John:

“I saw the Holy City, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride beautifully dressed for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, ‘Look! God’s dwelling place is now among the people, and he will dwell with them. They will be his people, and God himself will be with be with them and be their God.’”

Gloria in excelsis Deo: glory to God in his heaven, incanted the assembled, and Germain blessed the water in which those present would be dipped soon afterward, bonding the faithful to the holy mysticism of this sacred place.

The ceremony finished, the remains of King Childebert were taken down to the crypt that awaited him, and which he himself had designed only a short time before.

* * *

Barely had Childebert been laid to rest than it became necessary to face the somewhat delicate issue of his succession. His widow had only given birth to girls. There was no law preventing a female from being crowned, but the issue didn’t even come up. No one thought even for an instant that it would be possible for a Frankish kingdom to be ruled over by a woman. What was required was a vigorous male, handy with the sword, ready to have at the enemy, a rough-and-tumble kind of guy who wasn’t afraid to slay a few Visigoths.

Of Clovis’s four sons only Clotaire, the nephew killer, was still alive, and thus it was to him that the mantle was passed. He succeeded in reuniting the four states of his deceased brothers. Now he was the sole inheritor of the immense legacy of his father, meaning all of Gaul, augmented by the region of Thüringen, located on the other side of the Rhine; Burgundy; and several provinces in the Midi, or southern France. And what was the first thing that this all-powerful king, whose realm now extended across a good part of Europe, did? He left his residence in Soissons—for he lived there as well—and headed for Paris. The master of such an empire could only govern it from the banks of the Seine. No strategic thinking went into the decision. He was following no rule and adhering to no tradition: it was simply that Paris, inevitably, had come to seem the capital of the great realm taking shape.

Clotaire, however, was no longer a young man. He was past sixty, and worn down by the numerous military campaigns as well as the six wives whom he married either successively or simultaneously—marriage not yet being considered a sacrament by the Church. Clotaire could quite happily do what he liked and polygamy was a well-established tradition among the royal families. Clotaire ruled only three years until his death in 561, when he was somewhat stupefied to learn that God had apparently refused immortality even to a monarch as considerable as he.

“Alas! Who is then this king of the Heavens who would allow one of the most powerful kings on Earth to die?” he asked before closing his eyes for the last time.

While the monarch’s body was being carried to Soissons, Chilperic, the youngest of his four sons, tried to seize control of the kingdom for himself. He took command of the paternal treasury and ran to the Cité palace to distribute gold coins to the ministers and administrators. Blinded by such largesse, the court immediately celebrated him as the legitimate king.

When one knows the twisted mind-set and unbridled ferocity of the Merovingians, one can easily imagine that the three other brothers were not simply going to stand by and let this gold-distributing usurper triumph. They marched on Paris with their soldiers and rapidly put this self-proclaimed sovereign in his place. After several debates and not a few shouting matches, the four brothers got things worked out. Guntram would take over Burgundy and Orléans; Sigebert would have Austrasia all the way to the Rhine; Chilperic would have Neustria with its capital of Soissons. And Charibert would inherit Paris and with it Western Gaul.

* * *

In Charibert Paris had a king who was peaceful and moderate, a friend of the arts, and a defender of justice. His personal habits tended toward the dissolute end of the spectrum, perhaps, but he was nonetheless respected by one and all. In this year of 561, the capital of the kingdom had not much changed over the course of two centuries. On the Left Bank, a network of interlacing streets led to the forum, to the thermal baths, and to the arena, which, no longer in use, had slowly disintegrated before yielding to fire and to neglect. In fact, what had really changed in Paris were the numerous churches, cathedrals, monasteries, oratories, and sanctuaries that had been raised on the Île de la Cité and on both sides of the river. They were everywhere. Some of these sacred spots had been built hurriedly, consisting merely of a few planks of wood, but most rose up to heaven with their proud stone towers. And the palace of the bishop, the seat of the Church’s authority, was still on the island, surrounded by Saint-Étienne. Paris was ostentatiously Christian.

The builders of these sacred places could construct them at their leisure: under the authority of Charibert, there were no military misadventures and fewer plots were hatched. It was a peaceful period. After all, how could a king find the time to go to war? He was distracting himself with any woman who came close. In the end, however, it was deemed better to live under a king who chased skirts than one who chased armies.

This kingly appetite for women of Paris was not, of course, to the clergy’s liking. The prelates got together and furiously reproached the king for his concubines, and particularly for having married the sister of one of his wives, which canon law regarded as incest. An epidemic that decimated the population of Paris demonstrated celestial wrath, and Germain, still the bishop of Paris, threatened the king with the ultimate punishment of excommunication. Charibert pacified his holy brethren by renouncing his wife’s sister. He then married a saintly lady who was widely admired. This marriage represented more than a mere moment of sobriety for the king. Charibert had fathered only daughters up to now and needed to sire a boy, a future king to rule over Paris.

He was disappointed in this. He rendered his soul unto God in the year 567 near Bordeaux, during the course of one of his periodic visits to his southern holdings.

* * *

And so it started all over again. His three brothers—Chilperic, Sigebert, and Guntram—fought each other like wolves over the inheritance until finally agreeing upon a more or less equitable division. That left the crucial question of what to do about Paris, which each brother felt he deserved. Ah, Paris, the true capital of the Frankish kingdom. Whoever possessed it would be more kingly than the others. None of the brothers wanted to give it up, and so instead they agreed upon a form of joint ownership: the revenue raised there would be divided into thirds, and none of the brothers could enter the city without the agreement of the two others. A triple and solemn sermon, preached over the relics of Saint Martin, Saint Hilary, and Polyeuctus confirmed this arrangement. Paris had three kings.

For seventeen years, no one knew exactly who ruled the city, but its inhabitants did well by this arrangement. All the fratricidal bloodletting was taking place elsewhere. Thus, when Sigebert was busy pushing the barbarians of the east, Chilperic took advantage by wresting Reims from his absent brother. Once he returned to his estates, Sigebert took back his city and, in revenge, wrested Soissons away. A new invasion by the barbarians took Sigebert beyond the Rhine but this time the king was taken prisoner, and only released after a substantial ransom had been paid. This process emboldened his perfidious brother Chilperic, who picked up the war against his brother. Surrounded in Tournai, Chilperic was defeated, and his only way out lay in a rout of the enemy troops. To pull this off, he would have to kill his brother Sigebert, which might instill panic in the ranks of his soldiers. In short, Chilperic hoped through trickery and crime to gain the victory denied him by means of arms.

In the month of December 575, two henchmen surprised Sigebert in Vitry-en-Artois and planted their scramsaxes—small swords whose right edge was soaked in poison, the weapon of choice of the Merovingians and their bodyguards—in Sigebert’s chest.

“Here is what the Lord said through the mouth of Solomon: he who digs a ditch in his brother will suffer the same fate,” pronounced Germain with a groan.

Indeed, nearly ten years later, Chilperic himself was assassinated, stabbed during a hunting party by an unknown assailant who managed to escape.

Guntram, the last of the brothers, became the sole king of the Franks in 584, and was a figure in keeping with the times: unctuous and violent, wily and brutal. He was fiercely religious, indeed as devout as one could have wished. The people attributed to him miraculous cures and the bishops called him Saint Guntram, which was the very height of toadying.

Still, Guntram did rule with intelligence. To avoid being disemboweled by his nephews, and to prevent his family from being liquidated, he convoked in Paris a Gathering of the Great. He managed to turn the family tendency for aggression toward a common enemy: the Visigoths. The war against this people who ruled over Languedoc in the south of France turned out to be fruitless, but it really didn’t matter, for it temporarily preserved the Merovingian dynasty from assassination plots.

Unlike so many others in his family, Guntram died peacefully in his bed in 593 at the age of sixty-eight. He left behind a daughter, who quickly became a nun, and thus the realm was divided between Sigebert’s son, Childebert II, the king of Austrasia in the east, and the son of Chilperic, Clotaire II, who was nine years old and the king of Neustria in the west.

In 613, murder and disease had reorganized the family ranks in such a way that Clotaire II was able to unify the Frankish kingdom under his sole authority, though it was a kingdom torn between Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy. Perhaps it was for that reason that he chose not to live in Paris but in his palace at Clichy, located northwest of the Île de la Cité.

In any case, it was in Paris that he convoked a grand council whose purpose was to revamp the kingdom’s clergy. In October of 614, seventy bishops and everyone whom the country deemed its officers and noblemen gathered around the tomb of Clovis in Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul. Clotaire II made a push to preserve his royal authority and the unity of his estates.

After a week of debate, an edict was announced. The council granted to the clergy the power to judge the righteousness of its decisions, which henceforth would have by royal proclamation the power of law. In exchange, the council promised the nobility certain reparations for the damages caused by the years of war and internecine struggle. Thus a kind of order was established over the kingdom. In fact, with impressive diplomatic skill, Clotaire II had established the groundwork for centralized monarchic power.