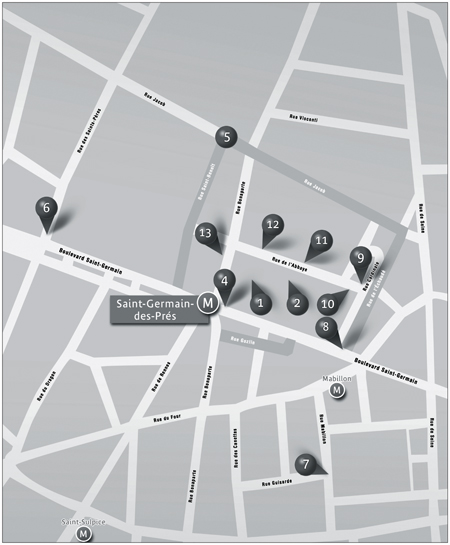

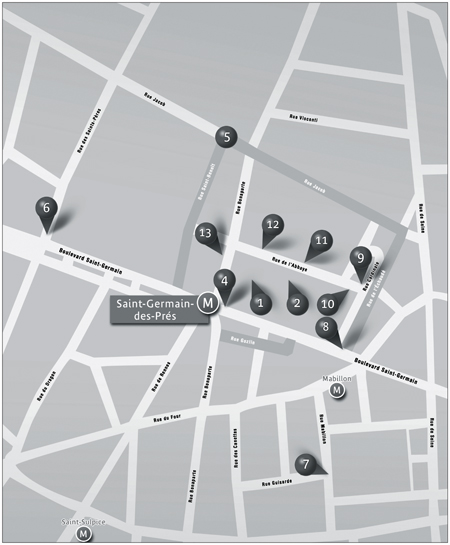

1. The Saint-Germain-des-Prés church. Its foundations, still visible in the Saint-Symphorian chapel, go back about 1,500 years. 2. The one remaining clock tower of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. 4. Walk along the right side of the church and follow along the Boulevard Saint-Germain, and you will notice the sharp edge of a wall jutting out into it. Baron Haussmann and his demolition crew cut straight through here to create Boulevard Saint-Germain. 5. The former boundaries of the Saint-Germain courtyard. 6. Remains of the Saint-Pierre church, located at what is today 51 Rue Saint-Pères. 7. Vestiges of the Saint-Germain Fair on Rue Mabillon. 8. Rue de L’Échaudé. 9. Home of the bailiff. 10. Home of the cardinal, at 3 and 5 Rue de l’Abbaye. 11. Chapel of the virgin, at 6, 8, and 10 Rue de l’Abbaye. 12. Remains of the monks’ dormitory, at 14–16 Rue de l’Abbaye. 13. Looking right from 16 Rue de l’Abbaye, an angel statue stands in front of a round tower (accessible by going into 15 Rue Saint-Benoît), the last vestige of the abbey’s defensive wall.

Seventh Century

Saint-Germain-des-Prés

From One Abbey Emerges Another

Arriving at the Saint-Germain-des-Prés Métro station, the first things that come to mind are Existentialism, jazz clubs, writers huddled for warmth at tables near the stovetops of the Deux Magots, and of course lovers embracing at the Café de Flore. These shadows have never entirely vanished from our minds. This is all an illusion, of course, for Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, just like Boris Vian, Jacques Prévert, and all the others are long gone. In his or her quest for them, the literary tourist will find only a somewhat pathetic sign stuck on a post at the edge of the sidewalk. PLACE SARTRE-BEAUVOIR, it proclaims. The city elders clearly believed it necessary to offer at least a small nod to touristic nostalgia and came up with this dual attribution, posted in a noisy and busy intersection facing the Rue de Rennes and right at the spot where it plunges into Boulevard Saint-German.

The stones of the Romanesque clock tower are more than a thousand years old, and the foundations, still visible in the Saint-Symphorian chapel, date from the same Merovingian period, meaning they go back about fifteen hundred years. The steeple rises up over the neighborhood, somewhat desultorily witness to the sad truth that high-fashion clothing stores have replaced the bookstores to which, not so long ago, students came seeking intellectual nourishment.

Walk along the right side of the church and follow along the boulevard. You will be stopped short by the sharp edge of the wall jutting out into it. It is as if some power could still cut straight through the jumble of buildings, a power that, once upon a time, must have been far greater than today. And indeed this stony interruption was formed by the remains of an ancient and powerful abbey. It juts into the street because during the Second Empire, Baron Haussmann and his demolition crew cut straight through here to create Boulevard Saint-Germain.

The construction nonetheless allowed the archaeologist Théodore Vacquer to undertake digs along the edges of the new construction sites, and to find one of the richest collections of Merovingian artifacts, which today are conserved in the Musée Carnavalet.

Farther along is a delightful Renaissance particularity: the southern door of the abbey, which was covered up at the end of the sixteenth century. Here one would have had a view of three ancient clock towers, of which only one survived the Revolution. The other two were so badly damaged that they had to be taken down. In fact, during the Revolution, the church was turned into a saltpeter storehouse, saltpeter being used in the manufacture of gunpowder for cannons, and this caused the ancient walls to blister. By introducing this destructive substance into this place of worship, the sans-culottes (as French revolutionaries were known) were intentionally rotting out this religious edifice from within. It is a miracle that the church of Saint-Germain-des-Prés managed to survive in one piece.

Everything here and in the adjoining streets evokes the history of the Saint-Germain-des-Prés abbey, so named to distinguish it from the Saint-Germain-l’Auxerrois and because it was surrounded by large fields (a pré is a meadow) of which it was the proprietor. Indeed, once upon a time, the church possessed the entirety of what are today the Sixth and Seventh Arrondissements.

The Benedictines were the masters of this prosperous terrain, with its orchards and vineyards, bringing in considerable revenue. This didn’t prevent them from also requiring payment for the right to fish in the branch of the Seine which they had formed by diverting the river in order to obtain an ample source of water. Until the seventeenth century, what are currently the Rues Gozlin and Bonaparte were submerged.

A township gradually developed up around the abbey, to the point that its inhabitants demanded to have their own parish: the Saint-Pierre church located in what is today Rue des Saint-Pères (a corruption of “Saint-Pierre”). By this point you could clearly see the outlines of a village that once was. It went from Boulevard Saint-Michel all the way to Rue des Saint-Pères, and from Rue Saint-Sulpice to the Seine.

The meditations of the monks of Saint-Germain-des-Prés began to be disrupted by the rowdy students from the Latin Quarter who liked to walk on their property. These students were particularly numerous during the Saint-Germain Fair, which took place at Easter around the abbey. Actually, the monks put up pretty well with these disruptions to their routine, for they benefited handsomely by collecting taxes from the merchants and their clientele. A place for shopping and strolling, the fair drew the rich and poor alike, the great and the modest, all of whom came to see actors, jugglers, and animals. Gaming took place here. Henri IV lost somewhere close to three thousand silver écus at the fair.

Quarrels, fights, and petty thievery were common fair occurrences, until the day, at the end of the eighth century, when the students started an outright riot. In order to preserve the peace Philippe IV—known as Philippe the Fair—took over management of the fair. This was a grievous loss to the abbey, given all the extra income that it had generated for the friars. The fair and its beneficiaries, meaning the Benedictines, eventually got it back two centuries later, at which point they again profited from it, an arrangement that lasted until 1762. One night in March of that year a fire destroyed the fairgrounds. Everything was reconstructed, but it wasn’t the same. Finally it was closed down completely during the Revolution.

The area was brought back into the jurisdiction of the City of Paris, which constructed the current Saint-Germain Market. At first glance, all that seems to remain of this place are the fairly common-looking buildings constructed at the end of the nineteenth century. But if you look more closely you can still find vestiges of earlier days: in the slope of the little streets, or the playgrounds of the Rue Mabillon, or the cobblestones of the ancient fair down below. A stone stairway still leads down to the ancient level of the street and treading upon this little paved irregularity can still bring back echoes from the past—the cries of the fair vendors and the roughhousing students.

* * *

One can also still do the tour of the Saint-Germain courtyard, which now extends across four streets but whose trace can yet be seen: the Rue de l’Échaudé to the east; Rue Gozlin to the south; rue Saint-Benoît to the west; and Rue Jacob to the north.

The first of these is quite curious. A medieval holdover, the Rue de l’Échaudé has a central channel right down the middle that once was used to wash away whatever the denizens of the street at the time threw into it from their windows. Better ways of taking away garbage have since been found, but the little street is still very quaint. Walking it you have that feeling that each section of it doesn’t belong to the same street, as if an imaginary wall separated one side of the street from the other, whose building styles are representative of different periods. Actually, there was once a wall there—that of the original abbey.

During the time of the Hundred Years War, a tight triangle was formed between the fortress wall later built by Philippe Auguste, a few dozen feet of the Rues de l’Odéon and Dauphine, and the inner court of the abbey. This constituted a no-construction zone, given that even the smallest structure would have enabled a potential assailant to get over the abbey wall. When this danger receded, this little zone of protection lost its purpose; buildings began timidly poking their nose into it, adapting to the tight angles that now were open to construction. The Rue de l’Échaudé has a pointed nose, and now you know why.

But what was “scalded” (échaudé)?

The “scalding” of the street’s nämes referred not to boiling water, but to a kind of pastry that was and is still a favorite in the Aveyron regions. The échaudé was a cone-shaped pastry that had been boiled. It was because of the triangular conical shape of the houses along the street, which used to be called the “path through the ditches of the abbey,” that the street took the name of this delicacy, whose recipe dates from the Middle Ages.

At the end of Rue de l’Échaudé, at the corner of the Rue de l’Abbaye, is a very old house dating back six hundred years and characteristic of buildings of the fifteenth century, meaning narrower at the ground level than on the floors above, to permit the passage of carriages. This building belonged to the bailiff, the officer who decided the fate of prisoners detained by the abbey. There was no recourse for them to appeal to the king or the Paris council: until Louis XIV, Saint-Germain-des-Prés was a separate state within the city and had its own administration for justice, its own court, and even its own prison. Today, to the right of the church on Boulevard Saint-Germain, a bronze statue of the enlightenment philosopher Denis Diderot, watches over the place where the jail once stood.

The abbey possessed a head abbot, a cardinal whose palace at the end of the sixteenth century, located at number 3 and number 5 Rue de l’Abbaye, was long considered one of the most beautiful residences in all of Paris. It remained a testament of Renaissance architecture and an example of religious opulence.

There are other vestiges at numbers 6, 8, and 10 along the same street, which were still in the heart of the former courtyard of Saint-Germain-des-Prés: the remains of the Chapel of the Virgin and its adjacent properties, and the buildings in which the monks lived their lives. Even if fragmented, disjointed, and ruined, the remains speak to the splendor of an age—the thirteenth century—when people came to Paris from distant regions to find intellectual stimulation and relief from petty cares, which they thought studying with the Benedictine monks would provide. The architect of Sainte-Chapelle, Pierre de Montreuil, designed the stone lacework of the Chapel of the Virgin. Several pieces of it can be seen in the small northern square of the church: the ornate curvature of delicate rosework that you would think came from Notre-Dame, or some tombstone, and the remains of wells. The great master builder has been buried here since 1264, contained within the fragments of his work whose foundation stones now comprise the interior walls of boutiques on the Rue de l’Abbaye. Incorporated into contemporary life, these vestiges nonetheless allow us to look back centuries. Even if they cannot speak, the stones convey sensation, color, and light to anyone willing to look and listen.

If you want to see them for yourself, go to 14–16 Rue de l’Abbaye. You won’t regret it. This modern building contains a section of the abbey’s past. Once the door has been closed behind you, in the silence and the kind of reception appropriate to such a place, you will discover to your right the remains of the monks’ dormitory. On the adjoining wall, separating the refectory of the house from the guesthouses of the abbey, the stone moldings remind you of windows. If you lift your head to admire them, your line of sight will take you to vestiges half enfolded into the wall. Imagine monks coming and going beneath the vaults whose majestic height was such that they remained untouched by the Revolution. Here you find a perfect example of the modern assimilation of medieval remains, because the combination of the chalky purity of the renovated stones, artfully illuminated by both natural lighting and spotlights, seems like the creation of some fantasist playing with time and styles.

From 16 Rue de l’Abbaye look over to the right. You will see an angel over the building facing the church. And behind it, a round tower, accessible by going into 15 Rue Saint-Benoît. This tower is the last vestige of the abbey’s defensive wall, constructed in the fourteenth century, shortly before the Hundred Years War.

In the seventh century, of course, this whole neighborhood hadn’t even started to form …

* * *

The centralized power imagined by Clotaire II was shaped by Paris, subject to the endless comings and goings of important figures from all the regions of the country. The king himself left less often, and sent only the occasional emissary out to his states, but he received at the Palace of the Cité the sons of the nobles and members of the clergy who came to solicit something or bring him news of their distant provinces. Little by little, the king abandoned his villa in Clichy and settled in Paris, the center for decision-making.

Beginning in this period one “climbed up” to Paris, as believers in the word of the Bible “climbed up” to Jerusalem. The Parisian population thought itself rather superior to all the other cities in the kingdom. Had not King Clotaire walked its muddy streets with his queen and his son, Prince Dagobert? This proximity to royal grandeur swelled the heads of the city’s inhabitants slightly, or so some would have us believe.

In any case, the other regions of the realm grew envious; they, too, wanted to have a king living among them. Hence Clotaire sent his son Dagobert to Austrasia. For a number of years, this young man of twenty-three had studied the affairs of state and proven an effective counselor to his father. But now all that was changed. He had to leave Paris and head to Metz, to administer the lands of the east. For seven years Dagobert played the role of assistant king, until his father died at the age of forty-five, in October of 629. As soon as his death was announced, Dagobert left Metz to attend the royal funeral in the Saint-Vincent-Sainte-Croix Basilica, which is also where both King Childebert, Clotaire’s great-grand-uncle, and Clotaire’s father, Chilperic, were interred.

In the choir of the church were numerous Gothic effigies of the kings of the seventh century. That of Childebert, which was discovered in excellent state and represents the oldest tomb effigy in France, was put in Saint-Denis.

* * *

Dagobert was never to return to Austrasia. He moved into the Cité Palace and quite naturally it was he who was given the Frankish crown—a crown slightly gnawed at around the edges, for Dagobert had a half brother named Charibert II, a slightly deranged lad, though such a handicap did not stop the Merovingian family from being once again divided in its succession. Brodulf, Charibert’s maternal uncle, and an ambitious and sly individual, demanded for his dear nephew half of his inheritance. Moreover, he claimed that this was what the deceased Clotaire had wanted. Everyone had some difficulty believing that the former king would have wanted to cede a part of his kingdom to the family simpleton, so Brodulf produced witnesses. Former counselors maintained that not long ago they had heard their master express edifying thoughts about Charibert II’s virtues. Interrogated harder, they started to waffle. Then they threw in the towel altogether. Actually, no, they knew nothing and had received no special confidence, and did not know the former king’s true intentions.

His ploy uncovered, Brodulf took flight to Burgundy and the banks of the Saône River, where his wife was mobilizing a few allies. Would the debate over the inheritance of Clotaire go on forever? As it turned out, it didn’t, because good King Dagobert had the evil Brodulf assassinated, putting an immediate end to all machinations.

Given that Charibert was, after all, of royal blood, it was necessary to offer him some kind of consolation prize. He was given the kingdom of Aquitaine, with its capital, Toulouse. His kingly title was a fiction, in fact, because the shy Charibert was entirely under the thumb of his half brother. After three years, he had the good sense to die, disappearing from the pages of history. But he left a son. And on it would go, for one day this child would demand his part of the kingdom. As the adage has it, governing means foreseeing. In the name of the unity of the Frankish kingdom, the infant was promptly suffocated in his crib. And that’s how the business was handled. Dagobert was not the sort to let himself be thwarted by a baby.

From that point on, Dagobert ruled as absolute master. The Cité palace became, more than ever before, the center of power. From Metz, Limoges, Rouen, Lyon, or Bordeaux the prominent and wellborn sent their children, both boys and girls, to take the air of the Parisian court. They came to Paris in the way that French kids today do internships in London or New York: to learn and to make useful connections. Where else could you network with young people from Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy? Where else could you meet young people who had come to learn good manners in the Frankish capital? Thus did King Edwin, the sovereign of North Umbria (in the northeast of England) have his two sons educated in Paris, convinced that they would find in King Dagobert the model for a powerful and respected monarch.

In Paris, the nobles from the provinces were initiated into all the necessary arts. A wellborn boy needed to learn how to use weapons, as well as rhetoric and law. Young noblemen were prepared to become both good soldiers and perfect administrators.

Paris was also the place for amorous adventures—whether passing fancies or promises exchanged for life, the pleasure of one night or a definitive engagement. The young discovered love on the Île de la Cité, and in the process brought about the union of families from different regions, regions that were sometimes in conflict, but which suddenly found the advantages of peaceful coexistence, particularly if one had royal ambition. People came to study, or to use a sword, or to marry if necessary, but intrigue and interests always lurked. The families watched over their offspring and counted on them to draw substantial benefit from their loyalty to the court. These benefits could take various forms—influence, territory, gold coins, or titles. For example, a certain Saigrius left Paris with the title of count; a Radulf was sent as a duke into the border regions of the north; a Desiderius made the contacts that later proved indispensable for getting himself named bishop of Cahors.

Conscious of status, Dagobert had his throne installed in the great hall of the palace, a seat fashioned by Eligius, his personal goldsmith, and a man in whom he placed so much confidence that Eligius would be appointed silversmith of the realm, and then a bishop, and even eventually be canonized, entering history under the name of Saint Éloi.

Why did Dagobert wear his underwear backward?

According to a French children’s verse, good saint Éloi once remarked to good king Dagobert that he was wearing his underwear backward. A bit of an anachronism, because said underwear is actually a culotte—puffy shorts that went down to the knees—which would be re-created by inspired fashion designers about a thousand years later. French Revolutionaries came up with this old rhyme to make fun of all the kings and all the saints. The radicals ridiculed royal pretension or, in one of the bawdier versions of the song, poked fun at the supposed love between King Dagobert and Saint Éloi. This was love in the wrong direction, exactly like the king’s culottes. Finally, as His Royal Majesty hurriedly “put them straight,” morality was preserved.

However, the future saint wasn’t yet the skilled artisan he would later become. The throne, with its rustic leather slats, was not all that comfortable. Still the frame shone with gold-ornamented bronze and was intended to make an impression, with its armrests thickening out to turn into the heads of lions with open jaws. Dagobert’s throne today is kept in the Medal Room of the Bibliothèque Nationale.

As a mark of his absolute power, Dagobert needed symbols such as this throne. But they weren’t enough; he also needed to inscribe his greatness into stone. Paris already had its abbey, and so he turned his eyes to the sancutary of Saint-Denis. Here he would construct the greatest of his monuments.

Profoundly religious and quite superstitious, Dagobert was persuaded that Saint Denis watched over him from on high. He could feel it, for once, long ago, when he had seen the sepulcher of the decapitated saint, Denis appeared to him in a dream in which the saint promised him protection, on the condition that once he had become king, Dagobert would build him the most sumptuous of all tombs.

Saint-Denis Church had been founded earlier by Saint Geneviève, of course, but in the century and a half that had passed since then, the place had become slightly dilapidated. In fact it was hardly more than a ramshackle little sanctuary located north of Paris; few pilgrims ventured in. About a dozen years before, a Benedictine monastery grew up adjacent to the holy place, and a small community had grown up around the monastery, consisting of a few farmers and artisans who made a modest living by serving the needs of the monks. But it was all a little sad and pathetic. Dagobert was determined to please his patron saint and to enlarge and beautify his resting place.

What Saint Denis required was a mausoleum as legendary as his story, and therefore a basilica would replace the rundown little church. Éloi was ordered to produce a reliquary appropriate to Saint Denis. Éloi fulfilled his mission, creating a first-class piece of work made of gold and precious stones with balustrades inlaid with gold, silver doors, and a marble roof. Denis’s disciples had to have been pleased: the remains of the miracle-working saint were finally housed in a sepulchre worthy of him. Éloi went further and exceeded the royal command: to receive the offerings from the faithful, he made a throne out of silver, and to exalt the faith of the believer, he created an enormous gold cross studded with garnets and other precious stones.

* * *

Dagobert was also thinking of the spiritual health of women. He founded a nunnery on the Île de la Cité, authority over which would lie outside the jurisdiction of the bishop of Paris. Aure, the first abbess, received the order directly from the hands of Éloi, and hence it was decided that it would be called Saint-Éloi. Before long, three hundred sisters were crowded within its walls. For their benefit two churches were constructed, one dedicated to Saint Martial, which is where the sisters would go to chant the service; the other was consecrated to Saint Paul, and into this church they retreated from the world. For those who enjoy looking through keyholes, we should note that these women, agitated by the military garrison that was given the responsibility of maintaining the security of the nearby royal palace, were so seduced by these handsome soldiers that eventually the community would be dissolved on orders from the pope. But that occurred five centuries later, enough time for several generations of good sisters to accommodate in their inimitable way both the sword and the holy-water sprinkler.

After that, Dagobert showered his favors upon the Saint-Vincent-Sainte-Croix Abbey. Naturally, the king’s pious generosity when it came to abbeys and convents was not without political subtext. The monarch was perfectly aware of the benefits he would gain by association with martyrs and saints. Religion was the guarantor of the realm’s unity; it could do what neither language, nor nationalism, nor tribalism could accomplish with a kingdom as spread out and diverse as Dagobert’s estates. Catholicism, with its procession of saints, its accumulation of relics, and its opulent churches and powerful abbeys, offered a means to unify in spiritual fervor the various parts of the Frankish kingdom.

Nonetheless, in order to confirm his authority, the king sometimes needed to collect money. To do this, he felt no compunction about turning to certain religious orders, whose riches were somewhat astounding. The palace constantly needed to fill its coffers to keep Paris, whose population was constantly growing, running, as well as to wage war against the Gascons and the Bretons, who were calling out for independence, or against the Slavs, who were threatening the borders. In order to pay for all this, Dagobert confiscated a number of lands that had belonged to the Church. The question was whether the monks would go along with this. As it turned out, they did, as the king played them off skillfully: he received the prelates and used his loyal follower Desiderius, the bishop of Cahors, to intercede on his behalf.

“When one has had the honor of working directly under the orders of Your Sublime Majesty,” pronounced the good bishop, “one knows that he is incapable of bullying the Church, and that only his sense of justice and his appreciation for what is necessary and right can lead for him to make such decisions.”

Following this episcopal declaration, the king made it known that this confiscating was not a matter of personal enrichment, but of maintaining security and unifying the realm. There was nothing to be said against this, and the bishops submitted to being stripped of riches without too much recrimination.

At the end of the year 638, Dagobert, though only thirty-five years of age, looked like an old man. His puffy trousers and the toga that he draped over himself couldn’t hide the fact that the king had lost a great deal of weight. His thick beard had gone gray and his beautiful hair now hung down limply. He suffered increasingly from inflammation of the intestines, and his hemorrhoids had become so bad that he was bleeding profusely. The doctors believed in bleeding patients, but this only succeeded in making him even weaker.

In the month of October, Dagobert asked to be taken to Saint-Denis. There was some question whether he would even survive the journey. To avoid being bumped around, he was conveyed in a wagon drawn by two oxen, which took small steps. Finally he reached his beloved abbey. After several prayers, Dagobert was taken to his villa in Épinay, where he had been born. Here he was not far from Saint-Denis and it was there that he had decided he would be buried. He had hesitated over this. Three years earlier he had asked to be buried in Paris, in Saint-Vincent-Sainte-Croix, next to his father. He modified his will, wishing to lie alongside the tomb of the holy martyr.

From Épinay, Dagobert ran the affairs of the realm, but when it was suggested that his son Clovis (the future Clovis II) be brought to him, a boy of only four, the king cried out, “The sight of a dying man is not fit for a child. I would prefer that he retain a better memory of his father.”

On January 19, 639, the king was found dead in his bed. The abbot of Saint-Denis planned an opulent funeral, but such was resisted, for it was pointed out that Dagobert’s private life had not been above reproach. He had had three wives—Gomentrude, Nanthilde, and Wulfegunde—as well as two known mistresses—Ragnetrude and Berthilde—and this didn’t include innumerable dalliances with servants, slaves, and the ladies of the palace. The abbot would brook no resistance, however. He could do no less than to have the man to whom the abbey owed its very existence buried with pomp.

What’s on Dagobert’s tomb?

In the thirteenth century, the monks of Saint-Denis wanted to pay homage to King Dagobert by building a unique tomb for his remains. But the king’s sulfurous reputation worried them greatly. They therefore came up with a somewhat ambiguous stone sculpture that looks something like a cartoon. The soul of the king, pictured as a naked child with a crown, is carried off to hell in the clutches of demons. Happily, Saint Denis, Saint Martin, and Saint Maurice succeed in delivering his soul, take him to heaven, and gain him admission into paradise. The message is clear: Dagobert deserved to go to hell and only the intercession of the saints miraculously prevented this. This rather peculiar tomb is still visible in Saint-Denis, near the main altar.

In Épinay, the king’s body was boiled in heavily salted water, a rudimentary method of embalming, and then his body was carried to his tomb in Saint-Denis. There were gathered all the great figures from all the regions of the kingdom. The palanquin bearing the king was brought in; he was dressed in the red coat of royalty, his hands joined together piously in prayer.

After Dagobert’s death, the Frankish kingdom was, once again, divided up, this time between two royal children: Sigebert III, who was but ten years old, and to whom was given Austrasia in the east; and Clovis II, a child of four, as we’ve seen, to whom was given Neustria in the north, as well as Burgundy. From this moment on and for quite some time, true power was held by the palace’s mayors, who acted as prime ministers and made all the decisions.

Clovis II would leave Paris and establish himself in Clichy. The Cité palace became an empty shell, which was occasionally reanimated, such as when an ambassador was being greeted or for grand convocations. Poor Clovis therefore took his place on the throne, his crown placed upon his long hair, like a true Merovingian. This poor pale-faced child, whose name was too much of a burden for him, simply watched events without saying a word, his great and innocent eyes opened wide.

The citizens of Paris were actually somewhat surprised when he came to town. He didn’t traverse the city on horse, as kings until then had generally done. Instead, he was carried in a wagon drawn by four oxen. The young king was perpetually ill and not strong enough to ride a horse; this was the most he could manage. The locals made fun of him for this, and soon enough had come up with what they deemed an appropriate nickname: the Lazy King. It stuck—both to him and to all of his descendants.

Nonetheless, on one occasion Clovis II displayed royal determination. When a famine was decimating Paris, he decided to take back a silver vessel that his father had given to the monks at Saint-Denis. He sold it and with the money bought wheat that he had delivered to the city. The abbot of Saint-Denis was outraged by this. Taking any of the abbey’s riches was a sin.

It would seem that the king looked with some disfavor on Saint-Denis and its riches. One day, deciding that he needed for his personal oratory in Clichy a holy relic powerful enough to ward off the devil, he went to Saint-Denis, and coolly ordered that the tomb of the saint be opened. Then, with a swipe of his sword he hacked off one of the martyr’s arms. After which, he left cheerfully, carrying the martyr’s arm under his.

Several months later, at the age of only twenty-two, Clovis II fell victim to a mysterious lethargy and the monks of Saint-Denis, who hoped to get their martyr’s arm back, made it known that the king had died young and in lunacy because he was being punished for his terrible sacrilege. The arm was returned to the crypt in the abbey and Clovis II was buried near his father.

From this second half of the seventh century, Saint-Denis saw its influence grow to the point of becoming an increasingly serious competitor to Saint-Germain-des-Prés, which, as we’ve seen, had been the necropolis of choice for the Merovingian kings.