n the medieval period, before the courts and the criminal law were in place with a full national system, and professional officers in the criminal justice system, punishment was manorial or ecclesiastic as well as implemented by the sovereign. Courts administered by the personnel of the lords of manors and by higher churchmen had capital punishment, and of course they had their own places of execution. A few miles from where I sit writing this there is a place called ‘gallows hill’. A study of any early ordnance survey map or of previous maps will soon locate several place-names with gallows in the wording.

n the medieval period, before the courts and the criminal law were in place with a full national system, and professional officers in the criminal justice system, punishment was manorial or ecclesiastic as well as implemented by the sovereign. Courts administered by the personnel of the lords of manors and by higher churchmen had capital punishment, and of course they had their own places of execution. A few miles from where I sit writing this there is a place called ‘gallows hill’. A study of any early ordnance survey map or of previous maps will soon locate several place-names with gallows in the wording.

A typical hanging cross memorial, at Hindhead. Author’s collection

The city of York, for instance, had several gallows, both within the city and in suburbs, with the church controlling most of these. In 1280 a certain John Elenstreng was sentenced to hang on the Ainsty gallows in York; he was a member of the Guild of the Hospital of St John of Jerusalem and, when he had been hanged, his brothers in that organisation took his body for Christian burial. But the story goes that he was still alive when taken to the chapel, and his recovery was seen as being brought about by St James. That was a rare case; in most instances, local gallows were busy throughout the centuries, and most of the hangmen are anonymous. The hangman would have been the person who held the whip when one observer in London in 1552 wrote, ‘The 13 January was whipped seven women at the cart’s arse, four at one and three at another, for vagabonds that would not labour, but play the unthrift.’ The hangman was a lowly figure indeed, reviled by most and pitied by few. When he was not hanging he was whipping someone; his only perks were the sale of the ropes and other mementos of the dead, and of course, money given to ensure a swift death.

St Leonard’s, York, close to the main execution site in the eighteenth century. The author

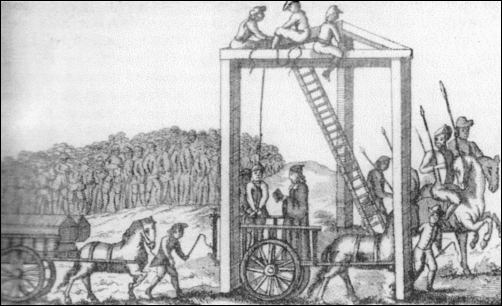

A hanging at Tyburn about 1680. From an old print

From the last years of the seventeenth century, after Monmouth’s rebellion and defeat at Sedgemoor (1685) and extensive witch trials, the death penalty was extended and what became known as the Bloody Code was established. By 1688 there was death waiting for perpetrators of fifty crimes; by the end of the eighteenth century the number of capital offences was 220. Obviously, the period of the French Revolutionary Wars and the wars with Napoleon (1790-1815) increased the level of paranoia in the British upper classes and the propertied new middle classes and so new capital crimes appeared on the statute books, such as the ‘administering of illegal oaths’ which appeared in the Luddite year of 1812.

When a change was considered, opinions such as this expressed by a writer to The Times (as recently as 1923) were usual: ‘I should like to register a protest against the view that there is a growing feeling in the country against capital punishment . . . Perverted sympathy for murderers and such mawkish journalism as “Move to save the Ilford Lovers” sap the very morals of a nation . . .’ Generally in those years of the French wars and after when there was the Chartist movement in England and regular riots, hanging was part of the fabric of life, something similar to a day at the races, and hangmen were popular with the press and the media, as in this rhyme written about William Calcraft in 1850:

My name it is Calcraft by everyone known

And a sad life is mine to you I now own,

For I hang people up and I cut people down,

Before all the rebels of great London town.

For my old friend Cheshire he learned me the trick

And I dine in the clouds tonight with Old Nick,

For the people on earth do use me so bad,

That with tears I could drown them for I feel now so sad . . .

In the period before the Bloody Code and the appearance of men like Calcraft, the hangings would be the responsibility of the County Sheriff, or of the Lord of the Manor, or of course, the abbot for church trials; the actual hanging seems to have been done by anyone who could be persuaded or threatened to do so, but the practice emerged of the hangman for a place being a criminal who took the job to save his skin. The practice was continued on the very simple principle expressed by George Savile, the first Marquis of Halifax, who said, ‘Men are not hanged for stealing horses, but that horses may not be stolen.’

The site of the original Tyburn today, near Marble Arch. The author

In the eighteenth century, the mediation of execution became more streamlined and the publishers took an interest. The ordinary of Newgate (the gaoler who sat with the condemned) became a criminal biographer and ‘last dying speeches’ became a popular genre. But also, the reporting of hangings steadily became more prominent and detailed. In earlier times, before prisons were equipped with execution facilities, many places would adopt the practice of hanging a felon near to where he committed his crime. A journalist writing in 1850 wrote about some instances of this:

It was formerly the usage, when a crime of remarkable atrocity had been committed, to execute the offender near to the scene of his guilt. The minds then exercised on these painful subjects judged that salutary horror would be inspired by the example so afforded . . . Those who were punished capitally for the riots of 1780 [The Gordon Riots] suffered in various parts of the town . . . The last deviation from the regular course was a sailor named Cashman who suffered death about the year 1817, in Skinner Street, opposite the house of a gunsmith whose shop he had been concerned in plundering . . .

There was always something especially ritualistic in the work of the hangman. At times they were even asked to publicly burn some offensive publication. Such symbolic actions suggest that the hangman was always the embodiment of that curious ambiguity: the Mosaic law of ‘an eye for an eye’ was at the basis of his work, but at the same time, everyone sensed that he was engaged in judicial murder. But before 1829, in a world in which there were no professional police, but only local constables and inefficient watchmen, there had to be a deterrence. Before the Victorian period, as historian A Roger Ekirch has reminded us in his history of nighttime, the dark brought with it horrible fears of violent crime: ‘In response to a midnight alarm in a Northamptonshire home, a small mob poured into the streets with forks, sticks and spears demanding the cause of the uproar.’ He also notes that in 1684, the whole village of Harleton ‘pledged their aid to Henry Preston, a yeoman who feared nocturnal attack by robbers . . .’

In 1701 an anonymous writer published a tract called Hanging, Not Punishment Enough. There had to be a horrendous fear extended to those who sought to break the law, and hanging, with the possibility of the body hanging in a gibbet or being sent to surgeons for dissection to follow, should have instilled terror. But the crimes went on, particularly those crimes brought on by sheer necessity, such as theft and poaching as families starved or simply carried on the traditional means of feeding children and surviving.

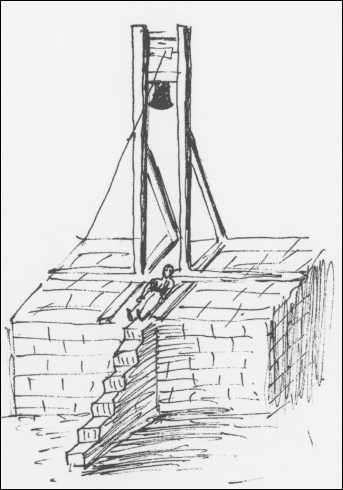

The Halifax gibbet. Author’s collection

Added to the attractions of hanging as a spectator sport, there was the other ritual of the confession. When writer Leman Rede wrote his collection of tales from York Castle in 1869, he ended every chapter with an account of any confession and remorse which took place. A voluntary confession by William Sheward in Norfolk in 1849 gives an example of what these confessions were, and what the interest was in the minds of the public eager for sensation:

On the 14th June, 1851, Mr Christie asked me to go to Yarmouth to pay 1,000 pounds to a captain of a vessel laden with salt.. On Sunday morning I was going on the above errand when my wife said, “You shall not go. I will go to Mr Christie and get the box of money for myself and bring it home.”

With that a slight altercation occurred. Then I ran the razor into her throat. She never spoke after. I then covered an apron over her head and went to Yarmouth

That kind of human drama is at the heart of the history of hanging and of the lives of the notorious hangmen; they were the men who terminated the narratives of the desperate, feckless or sometimes evil individuals who took lives, stole property, set fire to barns or counterfeited the coin of the realm. It was the hangman who closed the last scene, drew the final curtain, as it were, but of course, the players in the tragedy were not actors - they were mostly ordinary people, like the eager crowds at Tyburn, people who made mistakes, took too much drink, or allowed a passion to consume them against all reason. The hangman gave closure to all the issues, moral crises and storms of emotion in the execution tales.

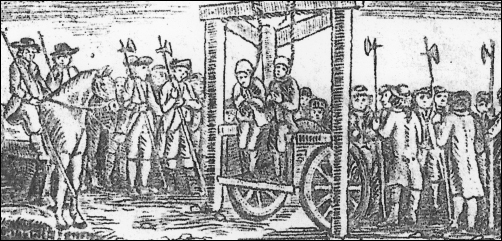

An old illustration to a very early hanging. Laura Carter

From the earliest phase of history in which the hangman became a professional, there was also the question of the relationship with the accused; the basic requirement was a quick death, and in cases of treason, when victims were hanged, drawn and quartered, clearly there was little hope of any deal being struck to lessen the agony and terror. But with such deaths as that of women for petty treason (which was the crime of murdering a husband until the 1790s) the normal death would have been burning at the stake, after being dragged on a sledge to the place of execution. It was common practice for the executioner to be given money to strangle the woman before she was anywhere near the pyre.

In some instances, usually with wealthy or notorious felons, there were special requests, as in the case of Captain Montgomery, who took his own life while waiting hanging at Newgate. He had previously requested to meet his hangman. But as the Spectator reported: ‘By another letter to Mr Wontner, it appears that he was desirous of seeing his executioner on the day before he was to die, a desire, of course, not complied with.’ But he avoided the noose. He was found dead in his cell, and the medical men found a quantity of prussic acid in his stomach on dissection.

It says a great deal about the character of the early hangmen when we reflect that, after the Gordon Riots in 1780, one of the condemned was the public hangman, Edward Dennis. After those riots, 135 people were tried; over half of these were transported, and twenty-one were hanged. Dennis achieved immortality because Charles Dickens, in his novel, Barnaby Rudge, notably in this passage:

“See the hangman when it comes home to him!” jeered one of his Fellow-prisoners.

“You don’t know what it is, “cried Dennis, actually writhing as he spoke.

“I do . . . that I should come to be worked off! I, I, that I should come!”

And, uttering another yell, he fell in a fit upon the ground.

‘The Last Dying Speech’. Courtesy of the Museum of London

In Scotland, the hangman was called the lockman. In Edinburgh, he was an important civic figure, typified by the life and work of John Ormiston, appointed in 1684. He came from a wealthy family with an estate in Dalkeith, but there had been debt problems, and John was clearly not a man of means, as he started his career in criminal justice as a servant to the master of a house of correction. But he then became hangman, and his executions took place in the Grassmarket. There was a gallows stone there, at the east end of the street. There were also hangings by the Market Cross. We know little about him, as is the case with most hangmen, and detective work needs to be done. Luckily for the historian, there was an account of Ormiston printed in 1834 in which he is not named but referred to as a gentleman ‘of reduced means’.

In keeping with most hangmen figuring in this book., it seems that Ormiston was profoundly affected by his unpleasant work. He almost certainly took his own life; the account of him in Chamber’s Journal describes this:

He would occasionally resume the garb of a gentleman, and mingle in the parties of citizens who played at golf on Bruntsfield Links. Being recognised, he was chased from the ground with shouts of loathing . . he retired to the solitude of the King’s park, and was next day found dead at the bottom of a precipice . . .

Pressing as well as hanging: Margaret Clitherow’s house in York. The author

It is obvious that the post of hangman was always a very stressful one. Virtually all hangmen on record developed problems with depres-sion, alcoholism or suicidal tendencies. In 1928, a lawyer called Charles Duff published a little book called A Handbook on Hanging, and in it he points out that hangmen were often in danger: ‘Towards the end of his career, our own Mr Ellis had personal risk . . . He was often threatened and sometimes had to have police protection, and even to carry a revolver for his own safety.’

In the course of development, there were no real refinements on hanging until William Marwood in the 1870s gave serious thought to making the death less drawn-out and agonising. At the London and York Tyburns it had been a case of using the ‘three-legged mare’ - a triangular frame made to handle several hangings at once, as happened with the Luddite hangings in 1812-15. The general practice had been to either stand the victim in a cart and then he would hang when the cart shifted, or to have a drop on a scaffold. Hence, with the latter practice, the space beneath the scaffold was available for friends and relatives of the felon to pull on his or her legs and quicken the end. The phrase ‘hangers-on’ derives from this.

But the noose itself was placed and made with no real thought other than being strong, and of good thickness. The best noose and rope were of silk, and a hangman would sell his silk rope after a hanging, to add to his perks. As to the thought of using a knot to speed the dying process, that was not a main element in matters; after all, a slow death was better entertainment for the crowd. People were in the habit of enjoying the hangings so much that they would book the best seats in nearby alehouses, in advance, to see the hanging. A clear example of this is at Lincoln. In 2007 the massive trees that were growing under the castle walls by Bailgate were cut down, and the visitor today may now clearly see what the view was like from one of the public houses to the hanging tower at Cobb Hall.

The York prison. The author

A picture of an execution at the York Tyburn c.1799. Author’s collection

In short, the social context to the following biographies of the practitioners of judicial death is one of gut-wrenching terror. The hanging days competed with the racing on the York Knavesmire where Dick Turpin met his end; the crowds lined Oxford Street to shout and jeer at condemned people heading from what is now Marble Arch where the Tyburn stood. Today., the historian has to work hard to imagine that terrible location. The gallows stood close to the junction of two roads just a few hundred yards down the road from the Arch itself. Today., tourists sit or stroll around that ground., many having no idea that they are walking on the killing grounds of Georgian England.

To appreciate the reality of what that dreadful and bloody history was., we have to look at the old prints., read the literature., and use the imagination in terms of sheer horrific empathy to even try to understand what it would be like to walk out onto a scaffold and feel the cap drop on the head and the hands tied. But we also have the museums and the heritage industry., from Madame Tussaud’s to the prisons. Maybe one of the most powerful statements from that disturbing criminal past is in an inscription written on a cell at Newgate where the infamous child-killer., Elizabeth Brownrigg., was locked up., waiting hanging. It read:

For one lone term, or e’er her trial came,

here Brownrigg lingered. Often have these cells

echoed her blasphemies, as with shrill voice

she screamed for fresh Geneva. Not to her

did the blithe fields of Tothill, or thy street

St Giles, its fair varieties expand,

till at the last, in slow-drawn cart she went

to execution . . .

Her skeleton was on display at the Old Bailey for many years. It is in this kind of gruesome history that the following accounts of the hangmen’s lives lie. It is impossible to imagine what it would have been like for a man to perform such killings. Most needed strong drink as well as a firm resolve, and many feared the crowd more than they feared the justice perhaps waiting for them in the life to come.