ohn Ellis was in office between 1901 and 1923, and in that period was responsible for the deaths of several of the most infamous criminals in the chronicles of British crime. Among his notorious clients are Herbert Armstrong, Dr Crippen, George Smith and Sir Roger Casement. He also had to hang women, notably Edith Thompson and Susan Newell. The latter was the first woman to hang in Scotland for more than half a century. Ellis eventually took his own life, and we have his autobiography, a work that includes his reflections on hanging women and also on the very famous clients he had during his career, a time in which he hanged 203 people.

ohn Ellis was in office between 1901 and 1923, and in that period was responsible for the deaths of several of the most infamous criminals in the chronicles of British crime. Among his notorious clients are Herbert Armstrong, Dr Crippen, George Smith and Sir Roger Casement. He also had to hang women, notably Edith Thompson and Susan Newell. The latter was the first woman to hang in Scotland for more than half a century. Ellis eventually took his own life, and we have his autobiography, a work that includes his reflections on hanging women and also on the very famous clients he had during his career, a time in which he hanged 203 people.

John Ellis. Laura Carter

As well as his own book, Diary of a Hangman, we have Jack Doughty’s detailed life of Ellis, The Rochdale Hangman, published in 1998. For present purposes, I will concentrate on the most notorious of his cases, and bring out the controversy surrounding them. His own memoirs were dictated, and then formed into a book with the help of other writers, mainly T J Leech. In those reflections, Ellis, a gaunt, solemn man with a bushy moustache, gives the reader a special insight into the process of becoming the public hangman in the Edwardian period. He started as assistant to William Billington, and he said that he applied after talking with his workmates about hanging one day and he said, ‘That’s the kind of job I’d like.’ He did not tell his wife that he had applied, so he had to explain the letter from the Home Office that dropped through the letterbox, inviting him to go to Newgate to learn the craft. His reasons for the application are not clear; he wrote:

Whatever the reason for it, it certainly wasn’t for any love of the gruesome. I’ve never been that sort of chap. I couldn’t kill a chicken, and once when I tried to drown a kitten I was so upset for the rest of the day that my mother said that I was never to be given a similar job again.

But off he went to London, and there Chief Warder Scott showed him the hangman’s room in the prison; he practised on a dummy person and learned about calculating drops and how to pinion someone. He reflected that the Newgate scaffold was taken to Pentonville after the prison was demolished in 1898. ‘I used it to execute Dr Crippen, Seddon, Casement and many others, he said, ‘It still remained one of the finest scaffolds in the country, and four men could be executed at one time on it . . .’

His career started when he was an assistant at the hanging of John Robert Miller who had killed a man in a fight. From William Billington he learned the right way on that occasion. It was a smooth job. William made it plain that studying the felons was the important part: ‘We went to look at the two men, for the condition of their necks and their general physique . . . Young Miller had been behaving in a truculent way . . .’ But on the day of the hanging, the deaths were swift, and the two hangmen took a brandy with the Governor after. It was the first hanging that he had seen, too.

Hanging Edith Thompson was something that deeply affected Ellis; he had hanged a woman before, Edith Swann, in Leeds. He wrote about them both in his memoirs. The Thompson case was the classic murdered husband in a love triangle template. The Thompsons lived a regular, hard-working life, and then she fell in love with Frederick Bywaters, a handsome young man who worked as a laundry steward with the P & O line. In October 1922, as the Thompsons were walking home from a West End show, Bywaters came out of the dark and stabbed Mr Thompson to death. Both Edith and Freddy were condemned to hang, and then the nation realised what a terrible thought that was – to hang a woman. Ellis was the man caught in the middle of that furore. He had a job to do.

Ellis recalled the hanging very clearly, and he wrote about Edith and Emily Swann and Sarah Newell. He said of the two working class women: ‘Both these women were coarse and rather vulgar, very different from Edith Thompson. Although that distinction shouldn’t tell in her favour, it undoubtedly did so with the millions of Britons, who without concerning themselves unduly with the executions of the first two women, held up their hands in horror when Mrs Thompson was sent to the scaffold.’

Hilldrop Crescent. Author’s collection

Ellis flew from Manchester airport to London for that job, and then was taken to Holloway where there was a massive crowd outside. He had to give a lot of thought to the intricacies of hanging a woman. He had extra help although he had never asked for it; his main recommendation was that the woman be given a large brandy, and he had a chair handy in case she had to be carried out and passed out before the rope was placed. When he first saw her she was ‘a pitiable sight’ and when she saw him, she behaved with dignity. Ellis realised to his horror that her cell was very near the execution shed, and that she would hear all the noisy preparations. But nothing could be done to change that. He calculated a drop of six feet ten inches, and then tried to relax and sleep.

In the end, it was extremely efficient; as Ellis said, ‘One flick of my wrist and Mrs Thompson disappeared from view. She died instantaneously and painlessly . . .’ Bywaters was hanged the same day at Pentonville. And he had written a statement declaring her innocent. Ellis was undoubtedly very distressed at what he had had to do. But there was another shock due to him when he got home, because he read that the aircraft he had flown to London in had crashed and three people had died.

The controversy about the Thompson and Bywaters case rages on, and the business has been the subject of fact and fiction in all kinds of contexts. The source of much of that is explained by Robin Odell, who has written: ‘Many of the letters which Edith had written to Bywaters were used in evidence at their trial at the Old Bailey in December 1922. Her suggestion that he might become jealous and do something desperate was offered as incitement to murder. The judge, Mr Justice Shearman, delivered a hostile summing-up, dismissing any romantic notions about Edith’s relationship with Bywaters. He said they were trying a ‘vulgar and common crime’.

The hanging of Dr Crippen is also wreathed in doubt and drama now, after new developments regarding his wife, whom he allegedly murdered in their home and buried under the floor in the cellar. Ellis said, ‘The only time I ever regretted being a hangman was during the Crippen case.’

The basic facts are that Crippen was hanged for the murder of his wife, singer Belle Elmore, at 39 Hilldrop Crescent, in London. He was having an affair with his secretary, Ethel Le Neve, and he had spread a tale around their circle of friends that Belle had gone home to America for a funeral. Crippen and Ethel (with her in disguise) boarded the SS Montrose when the hunt was on for them, trying to travel to the USA, but they were recognised by the captain, and he sent a wireless message – the first time this was done to clinch a murder hunt – and they were arrested. There was convincing forensic evidence, given by Sir Bernard Spilsbury, at the trial at the Old Bailey, and Crippen was sentenced to death. Ethel went to gaol but was later acquitted.

Inspector Dew, who made mistakes in the Crippen case. Laura Carter

Ellis reported that Crippen died with a smile. He wrote, talking about that massive case with huge media attention, ‘It got so bad that I dare hardly venture out of my own house . . . I was just too popular. After all, he was the man who was going to hang ‘that monster’. But on the day before his death, Crippen planned to take his own life, smashing his glasses to that he could cut his throat with a shard of glass. His attempt was discovered, as a vigilant warder saw that the glasses were not where they usually were. A search of the bed found them.

But Crippen was up early, ready to die. Ellis wrote that the man had a ‘set, calm expression’ and that the warders were more upset than he. The world waited for a confession from him; he had protested his innocence throughout. No confession was ever proved to have been made. When he walked to the scaf-fold, he was smiling. Ellis recalled:

As I stood on the scaffold I could see the procession coming into view . . . Behind the praying priest came the notorious Dr Crippen. If he had ever shown cowardice or collapse, he displayed none now.

Such was Crippen’s profile across the newspapers of the world that Ellis was offered the then massive sum of £1,000 to do a lecture tour of America, talking about hanging Crippen. Ellis refused. He had had a demanding November in 1910 – hanging four poisoners.

The first Ripper murder – Dew was involved in that investigation. Famous Crimes, 1900

The story of Sir Roger Casement is another tale that has spawned libraries of books and articles. He was an Irish nationalist from Dublin, who went into the British Foreign Service in 1892, and was knighted for his humanitarian work in 1911. He joined the Gaelic league and became an Irish Volunteer in 1913. Not only did he try to raise an Irish brigade in Germany, went to Ireland on a German submarine in 1916, and was then arrested. He was charged with high treason.

The great lawyer F E Smith led the prosecution against him, and Casement was sentenced to death. He had been charged with the kind of treason known as ‘adhering to the King’s enemies’ – a law going back to the thirteenth century. As Smith wrote later: ‘ . . . it was contended that this was an offence that could only be committed by a person present in this country. If this were true . . . than Casement had committed no offence. The defence were confronted by the fact that not only was there an unbroken line of legal opinion, from the sixteenth century onwards, dead in their teeth, but such decisions as there were, were necessarily few because such offenders took care to remain out of reach, were also against them.’ In other words, casement was in a ship, close to the land within the King’s domain, and was still obviously ‘physically present’ on British soil.

It was hard for the public at the time to gather any sympathy for Casement: this was made worse by the publication of extracts from his diaries, which showed him to be homosexual, something of course, vilified at the time, and only in Ireland was he a hero. His request for his body to be sent back to Ireland was refused, but in 1965 the body was exhumed and taken to Glasnevin cemetery in Dublin.

Casement died bravely. When Ellis and his assistant went to him in the cell to pinion him, he stood, unmoved, a tall and dignified man, offering no resistance or any trouble. Casement prayed, with Father McCarroll, all the way to the noose; his last words were, ‘God save Ireland’ and ‘Jesus receive my soul.’ The official posting of evidence of sentence and death was on the prison door, saying:

I, P R Mander, surgeon of His Majesty’s Prison of Pentonville, hereby certify that I this day examined the body of Roger David Casement, on whom judgement of death was this day executed at this prison, and on this examination I found that the said Roger Casement was dead. Dated this third day of August 1916.

Feckless and stupid people may have died on scaffolds in British history, but there were real monsters among the hanged, and one of these was certainly George Joseph Smith, the ‘Brides in the Bath’ murderer. Smith was born in Bethnal Green in 1872, and was a criminal from his youth, being in the reform school for stealing when he was only nine. Later, as a teenager, he did six months’ hard labour for stealing a bicycle. He was then in the army until 1896, and then he began a double life, with the use of aliases and a horrible need to ingratiate and rob all the women he could – choosing easy prey of course. But matters escalated when his violence came through.

When he met Beatrice Munday he had two wives already - instances of bigamy. When Beatrice made a will leaving everything to him, she was found dead in her bath. Smith had discovered a modus operandi that would make him rich and keep him free for more wives. He wed Margaret Lofty in Bath (a terrible irony) and then in London, after the insurance policy, she was found dead in her bath. The father of one of his former women saw the story and told the law. Soon Smith was tracked down and charged. In court, the jury took very little time to find him guilty. He was to be another client for the Rochdale hangman.

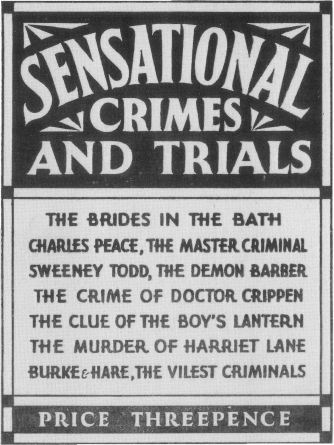

Front page of a booklet. Anonymous, 1935

Ellis and his new assistant, Edward Taylor, watched Smith as he walked in the yard beneath them, considering his height and weight. Ellis noted that this formerly dashing and healthy man of forty-three looked aged and pale. A drop of six feet eight was arranged. Smith made no confession of murder; he allowed no visitors and seemed controlled, but on the fatal morning he began to fall apart emotionally. The chaplain brought the condemned man out of his cell too early and he was shoved back inside. When eight o’clock approached, he was taken into the charge of the warders and they marched to the scaffold. When Smith saw Ellis he yelled, ‘I’m innocent of this crime!’ Then, even while the cap was put over his head, he said again, ‘I am innocent.’ Ellis had no problems ‘turning off that monster.

Ellis’s decline and death were indeed very sad. The mental stress and depression that attends on hangmen was seizing him. Around the late 1920s, as the economic depression hit home as well, Ellis felt even more strain. He tried to kill himself in 1924 by shooting himself in the face; but he survived, and of course he had committed a serious crime. His wife found him and rushed him to Rochdale Infirmary. At trial, the magistrates advised him to give up the drink. He was lucky to be merely bound over. Some money was earned by seeing his memoirs into the press: the Thomson group in Scotland paid him for writing Revelations of My Life.

But on 20 September 1932, he was drunk and ready to die; he had a razor and was violent towards his family, and he cut himself, dying in his own kitchen.

He had hanged women and teenagers as well as hardened villains and psychopaths. This had all given his constitution enormous strain. The Rochdale hangman was, in spite of all this, a true professional in the kind of work that very few have done well down the centuries. His wife, at the inquest, said that for the last two years, Ellis had suffered from ‘neuritis, heart trouble and nerves’ – this comes as no surprise when it is recalled just how many hangings he did and in what circumstances. The coroner said, ‘I am quite of the opinion that he did this rash act in a sudden frenzy of madness.’