Pierrepoints and the Last Hangmen

he Pierrepoints were to dominate the hanging business between the years 1906-1956. The story begins with Henry (Harry to his friends – though his job might have lost him some of those).

he Pierrepoints were to dominate the hanging business between the years 1906-1956. The story begins with Henry (Harry to his friends – though his job might have lost him some of those).

Harry Pierrepoint’s brother, Thomas, joined forces to execute Harry Walters on 9 April 1906 at the point when Wakefield’s facilities had been refurbished; the death cell and suite (as these areas of prisons were euphemistically termed) were on C Wing. The physical dimensions and technical areas of the scaffold were to receive much attention at various points in the history of hanging; in this instance, the suite consisted of two cells, one having been knocked through so that the condemned man could have some exercise without going out into the general yard.

These death cells were on a second floor landing; at Wakefield the whole place had been purpose built, with the section having a glass top and a beam and chain in a commodious area. A little later, there was to be a controversy about the dimensions of the trapdoor scaffold area, as we now know after the Home Office review in 1920, looking at the tendency of condemned persons hitting their heads as they were hanged (in some prisons). John Ellis was consulted, as we know from papers opened in 2005 in The National Archives, and he said that at Winchester prison in particular, the gallows trapdoors were too narrow. Ellis had recommended that these doors were too narrow and that the walk to the gallows was too long. The Winchester pit was much narrower than the one at Pentonville, for instance. This information, surfacing many years after the execution period, highlight the conditions under which the hangmen worked. Wakefield was clearly aware of the need to address the actual physical space of the scaffold.

In this new workplace the brothers got to work, leaving the rope to hang and stretch overnight, after the weights and rope being ascertained. It was an auspicious start to their partnership; all went very well, Tom was adept at marking the place where the man would stand, and at coiling the noose ready for use at the required height; then both men stood by the cell ready to move their man swiftly to the platform. Walters was pinioned and dropped in seconds.

In an account of Yorkshire hangmen, the question has to arise at some point: what would happen when a man from the hangman’s own town was to be executed? The answer to that is illustrated in the case of the Bradford killer John Ellwood. He claimed that he knew Harry well and that when the time came, he would create major problems for the hangman. Ellwood had committed a cool and very public murder. Ellwood had returned to the office where he had formerly worked, in Bradford, and timed his arrival at the time when there would be cash on the premises.

Ellwood had left the firm, Fieldhouse and Jowett, six months previously. He had been in a heated row with his employers and had left under a cloud; it was therefore not hard for the police to show that, as an employee, he would know the routine of the place in a typical week, and would therefore be aware that large amounts of money were brought to the building by the company every Friday. It was hardly going to be a problem for the investigating officers, to find the man who had beaten Tom Wilkinson to death with a poker in that office. There was plenty of blood on Ellwood’s clothes when he was arrested, and his pathetic excuse that this was caused by a bleeding nose was not going to fool anyone. The murder scene that day had been observed by a passer-by, to whom Ellwood had vainly tried to lie that he (Ellwood) had only called there to try to obtain his job back and that someone else must have been there in a murderous frame of mind. In court, there was evidence of a letter written by Ellwood saying that he would call that day, but nothing more than that.

The trial at Leeds was spoiled by a technicality, but he was convicted of murder, and then went to appeal. That last-ditch attempt to save his neck was dramatic in the extreme; on 20 November 1908, the applicant for Ellwood, Gregory Ellis, argued that at the trial there had been no motive for the murder satisfactorily stated or explained. A supposed letter from Wilkinson, asking Ellwood to come and discuss the reinstatement had been dismissed and the defence team at the appeal brought this up again. It all came to nothing; the judges were convinced that Ellwood had gone to the office that day with the attention to rob and to kill if necessary.

On 3 December that year, Ellwood had an appointment with the Pierrepoints. The killer had openly bragged that he would create a stir on the fateful day. They had to come up with a contingency plan, and it was decided that two guards walking with the group to the scaffold would stand on planks at either side of Ellwood to restrain him when trouble started. That would mean using the hood and pinions as he struggled or kicked, of course. But the most successful move was that the brothers had the man pinioned in that cell, taking him by surprise. There was no trouble after that, apart from the man’s shouts that he was innocent, even directing one call to his hangman, ‘Harry, you’re hanging an innocent man!’ After that, both brothers being convinced that he was not telling the truth, the only other words spoken by Ellwood, seconds before he dropped, were, ‘It’s too tight.’

Tom, like his brother, had written the usual application, made after John Billington’s death at Harry’s urging. Tom was interviewed and then went for the training at Pentonville. Of course, he had had some extra tuition from Harry and was well prepared. It seems that Tom was a ‘natural’ at the work, and he very smoothly adapted to work well with his brother. They were to be severely tested by one of the most bizarre executions ever done, and that was the hanging of Richard Heffernan in Dublin in 1910. The scene that was to emerge was one of tragic-comedy, but very dark comedy nevertheless.

Earl Russell’s idea for gas execution. Daily Sketch, 1915.

Heffernan had killed a girl called Mary Walker, stabbing her and then telling people that he had seen the murder. But fate had a string of stressful incidents lined up for the Pierrepoints. First, something happened that illustrates the essential need for the hangman to protect the privacy of his identity. For some reason unknown at the time, Harry’s name was on the passenger list of the ferry they were taking from Holyhead. People obviously began to take a vicarious and morbid pleasure in knowing who he was; the public hangman was always a figure of intense media interest. Wisely, he was given a private place to hide in for the journey.

The next incident in the Heffernan fiasco was that the condemned had been so unbalanced and determined to flout the hangman that he had set about clawing at his own throat to take his own life. In normal practice, suicide was high on the agenda of a hanging in the planning of the official personnel involved. The man was sedated and put on close guard. The brothers were aware that this was a highly unusual and challenging case. They knew that they would not only have to be acutely aware of the need for precise attention to all safety procedure, but that the victim was likely to do the most unexpected things at any time.

There were priests in attendance and they came to speak with the brothers on the night before the hanging; no doubt there was extended discussion of Heffernan’s condition. What Harry must have noticed - and it became important the next day – was that there was a very small space on the trapdoor area by the drop. What happened there the next day was that the condemned man strode into the trapdoor area with a gaggle of priests; he was weeping and praying and kissing the cross. But speed was the first consideration here, and even when Tom did his pinioning well and stood back, there were the priests, still on the trapdoor. There was no alternative: decorum must be broken, and the priests pushed hard out of the way. That’s what Harry did, and then down went the lever.

There was controversy in Harry’s life not long after this, and it led to his dismissal. The fuss began at an execution in Chelmsford at which the sensitive subject of the hangman’s need for drink arose. The fact is that Harry arrived to do the work, with Ellis as assistant, and he had taken a drink or two. It seems that, according to Ellis in a letter to the Prison Commissioners, that Harry had threatened violence to him: ‘ . . . he threatened what he would do for me, made a rush at me, but the chief warder and gatekeeper intervened and talked to him . . .’ Ellis added, ‘He is the first person that has ever assaulted me in all my life.’ He said that he and the prison officials felt that Harry had needed drink in order to do execution work. By July 1910, Harry’s name was taken from the official list of executioners.

The sign that Harry was being phased out was when Tom stepped into the chief executioner role; this was a job at Holloway. But in 1910, Tom handled his first Yorkshire execution at Armley: this was John Coulson, the most clear-cut and uncomplicated case in Yorkshire murder. Coulson walked around his workplace showing off a summons he had concerning violence to his wife and written on that paper was a statement that he had killed her. Suspicions were aroused and later, a constable found Jane dead at the family house, and Coulson in a deranged state, insisting that he had tried to take his own life. This had happened in Bradford so, again, Tom was in action in his own home town, among people he knew and who knew him.

Tom carried out the execution smoothly and swiftly; the most informative detail in the Coulson case, however, was in the ruse Tom came up with to slip away from the gaol unseen. He and the assistant, William Warbrick, pretended to be journalists and walked through the crowd, notebooks held prominently.

In 1911 Harry tried to put things right with the authorities and he wrote a long explanatory letter to the Prison Commissioners with reference to the Chelmsford affair. Harry included in that letter an implication that Ellis was acting unfairly, to ‘do Harry out of work’. He insisted that the report on Chelsmford was a lie and that Harry could have reported Ellis many times for various infringements. The letter ends with a note of special pleading: ‘I have a wife and five young children to keep and I can assure you I have had a lot to bear. I should be pleased if you would communicate with the Reverend Benjamin Gregory of the Huddersfield Mission and inquire about me since I came to Huddersfield this last few months.’

There was no reply. Obviously, there was no going back and certainly no second chance. Tom Pierrepoint was now the ‘number one’ and he had plenty of work in 1913. What is noticeable in that busy year is that normally Ellis and Tom worked separately, with different assistants. On just one occasion – in Worcester in June - Ellis was chief and Tom the assistant. It seems that there was tact and diplomacy at work, and in the Yorkshire hangings in the years from 1913 onwards it was usually William Willis or Albert Lumb who worked with Tom, although Tom did act as assistant on several occasions to Ellis in other counties, notably in the hanging of the famous George Joseph Smith at Maidstone in 1915, as we have seen in the last chapter. Smith, during his trial, said at one point, ‘You may as well hang me at once, the way you are going on . . . go on, hang me at once and be done with it.’ He was prescient indeed: in a state of complete collapse, he was handled delicately by Tom and Ellis.

Tom was to be hangman until 1946 and his work included several high-profile cases, but his brother Harry was increasingly desperate after his dismissal. What he did in 1922 sums up a tendency in most hangmen at some point in their careers: a need to earn some money from their notoriety. Berry and Binns had certainly done that. But now, Harry Pierrepoint wrote his memoirs for Reynolds News magazine. The articles were headed, ‘Ten years as Hangman.’ It was to be one of the last events in Harry’s life, as he died on 14 December 1922, at forty-eight. Arguably, his most poignant execution had a Yorkshire connection, though his victim was a Lincolnshire woman, Ethel Major. He hanged another woman, Charlotte Bryant, at Exeter; both females were sentenced to death for murder by poisoning of their husbands. Just before Christmas 1934, Tom Pierrepoint, assisted by his nephew Albert, hanged Ethel Major at Hull gaol. It was a traumatic experience for all the professionals involved but especially so for the man who had to pull the lever on the scaffold.

Ethel Major, living in Kirkby on Bain, not far from Lincoln, had a husband who was having an affair; she was a complex personality, tending to express herself in unconventional ways and to some she seemed naïve. She had had a child out of marriage, during the Great War, and then Arthur Major had married her. Ethel was from a rural family; her father was a gamekeeper. In many homes at that time there was strychnine used for various things, along with other poisons (the commonest being arsenic on fly-paper) and when Arthur was taken seriously ill, plain forensic work pointed the finger at Ethel, as she had the means and the motive.

Ethel Major. Laura Carter

There had been widespread debate on the issue of capital punishment in the early 1930s; one reason for this was the reprieve of a teenager sentenced to hang after a double shooting in Waddingham in Lincolnshire. But also there was the issue of hanging women and also the difficult topic of diminished responsibility. It would be useful and interesting for the public to know how the executioner stood on the matter and, unusually, Tom gave an interview to the Yorkshire Post in February 1930. Typically, he was interviewed doing his ‘day job’ at a foundry. His views were simple and direct: ‘I think it would be encouraging people to murder if the death penalty were abolished, but it would make no difference to me either way.’ Steve Fielding makes it clear that Tom put financial gain before moral debate, however.

Huddersfield gasworks, where Tom Pierrepoint worked at one time. The author

His resolve was certainly tested in the Major case. Young Albert had applied for the executioner post in 1931, stressing that his father had taught him well. He was twenty-six at the time and had been brought up largely in Huddersfield, where his father had at times worked at the gasworks. The new Pierrepoint team of Tom and Albert arrived at Hull and made ready to attend to Ethel Major. They would have known the salient points of the case – mainly that a dog had died, as well as Mr Major – but they would not have known how complex the whole affair had been and how it was to influence thought on capital punishment.

The preparation to hang Ethel major must have been highly unusual for Tom. She was a very tiny woman, only just under five feet tall and weighing only 122 pounds. Images of her available show her wearing unflattering glasses and an apron. She had not spoken for herself at the trial and revisions of the case show how terrible was her ordeal, but to the last she was calm, and it appears that she was an ‘ideal client’ for the Pierrepoints, going stoically to her fate. Young Albert was naturally intrigued by the thought of hanging a woman, as there was an emotional impact involved that needed some reflection. John Ellis spoke at length about his hanging of Emily Swann and Edith Thompson, and he could not resist talking at length about the sense of moral outrage involved in hanging a woman. But apparently Tom Pierrepoint knew the score when it came to the gallows for a woman victim. He reassured Albert that she would be controlled and said, ‘I shall be very surprised if Mrs Major isn’t calmer than any man you have seen so far.’

For Tom Pierrepoint, two days in January 1919 had him busy in seeing to the death of three soldiers. It had been the tail-end of the war and offences were common as men returned home to face all kinds of relationships problems; there was also a spate of crimes of violence often linked to ex-servicemen. The three hangings involved an assistant we know little about – Robert Baxter.

Benjamin Benson was the first to hang, on 7 January. He had been having an affair with a married woman, Annie Mayne, in Hunslet, Leeds. She was married to Charles Mayne but he had left her when her affair with Benson began and he found them together one day. Benson moved in to live with Annie, but she was a promiscuous type and had other male friends. Benson came home one day and Annie came home with a young soldier, taking him upstairs. Benson went to them and the soldier fled. But after that there was a confrontation and he hit Annie. The argument escalated into extreme violence and Benson took a razor and slashed her throat.

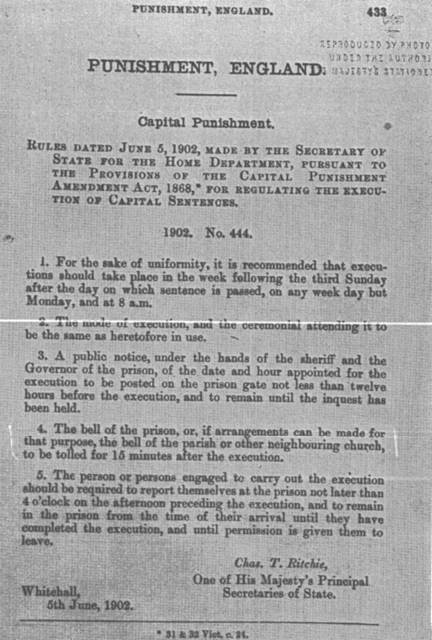

The 1902 rules for hanging procedure. HMSO

The following day Tom executed two young soldiers who had murdered a shopkeeper in Pontefract. These men were Percy Barrett and George Cardwell; they had murdered Rhoda Walker at Town End and then pawned some of the goods, even giving some jewellery to Cardwell’s mother in Halifax. They went to London, but the pawn tickets, as in so many cases, made it easy to track them down. They said they were innocent, right to the moment they stood on the trap.

The inter-war years were a time of prolonged and heated debate on all aspects of the criminal law. There had been two significant pieces of legislation which influenced homicide decisions, one in 1908 which raised the minimum age of execution from sixteen to eighteen, and the 1922 Infanticide Act which made that offence a variety of manslaughter rather than murder. Then, just before the hanging of Ethel Major, in 1931, there was the Sentence of Death (Expectant Mothers) Act in which pregnant women after giving birth were reprieved. Previously there had been the ‘pleading of the belly’ which meant that it would be a stay of execution if a woman were pregnant at time of trial.

These were all humane measures, long overdue, but the persistent problems were the nature of insanity in homicide, with the idea of diminished responsibility, and the difficult nature of a whole range of illnesses which an offender might be suffering from.

The Ronald True case of 1922 had an impact on the subject, largely because he had been, in the opinion of the press, ‘reprieved by the doctors’ and he was wealthy with powerful friends. Harry Pierrepoint, just before his death, commented to the press that there was a gross disparity in that, as another man, with a similar ‘crime of passion’ was hanged, and he had been poor. The papers talked about ‘trial by Harley Street’ and the Evening News wrote:

Mr Justice Avory’s terse and mordant comment on leaving the law to Harley-Street experts shows the country where it stands under a Home Secretaryship that says, “I am powerless when the doctors have spoken.” All you have to do after a trial, then, is to call in the pathologist, get his certificate, and leave that to confirm or reverse the verdict!

In 1923, writers to The Times on the debate made points which express common feelings at the time; one writer made the point: ‘Now what is our machinery? The judge has no option. With due solemnity, he passes sentence of death equally upon the miserable mother and upon the callous ruffian.’ Another writer noted that in his opinion, there was ‘a growing feeling in the country against capital punishment . . . there is an immense body of silent opinion against it . . .’

The year following there was a deputation to the Home Secretary pressing for the abolition of hanging. The groups involved included the Society of Friends, the Women’s Co-operative Guild and the Howard league for Penal Reform. The leading figures were George Lansbury, Major Christopher Lowther and Margery Fry. One of the most strident voices against the death penalty was the campaigner Violet Van Der Elst, a wealthy woman with land and status in rural Lincolnshire who made a habit of driving her large and showy motor vehicle to the prisons where executions were to take place and protest in front of the growing crowds of onlookers.

The hangmen carried on in spite of all the debate and disagreement, but of course, their written statements were valuable documents for both sides. Also in the picture were accounts of the alternatives to hanging, such as the campaign by Elbridge Gerry, founder of the NSPCC, to replace the noose with ‘humane’ electric death. He wrote many articles on cruelty and capital punishment.

In 1930 there was a Select Committee on Capital Punishment, led by Sir John Power. The crime of murder was the only issue, as since 1838 the only executions had been for that crime. The conclusion was that ‘The witnesses felt bound . . . to point out that in their view the risks to which the officers of the law were exposed in the discharge of their duties would be enhanced if capital punishment were abolished’ and furthermore, that

‘professional burglars and criminals of that type did not normally carry lethal weapons in this country and that was directly attributable to the gallows . . .’

One of the spin-off effects of this new caution and reflection was the nature of recruitment to the ranks of hangman. The Aberdare report of the 1880s had involved the testimonies of medical men such as this, and it was a sobering exercise for all concerned:

I descended immediately into the pit where I found the pulse [of the hanged Man] beating at the rate of 80 to the minute, the wretched man struggling desperately to get his hands and arms free. I came to this conclusion from the intense muscular action in the arms, forearms and hands, contractions, not continuous but spasmodic, not repeated with any regularity but renewed in different directions and with desperation. From these signs I did not anticipate a placid expression in the face and I regret to say my fears were correct. On removing the white cap about one and a half minutes after the fall I found the eyes starting from the sockets and the tongue protruded, the face exhibiting unmistakeable evidence of intense agony.

As a result of this, and of Binns’s blunders, things began to change. In addition to the expertise of the hangman, after 1913, the medical men present at an execution played their part in ascertaining the length of the drop. There is a difference in the tables of drops for 1892 as compared with 1913; for instance, the average range of weight, say 135-145 pounds, differs by almost a foot deeper drop in 1913. Authorities were taking no chances. There was much more consideration for ensuring a swift exit.

Albert, the last and most celebrated of the Pierrepoint hangman family, applied at a time when the results of these deliberations had an effect on recruitment.

The name of Albert Pierrepoint has almost become the definitive name that follows if the topic of hangmen comes up in conversation; in recent years it has been such a topic, largely because Timothy Spall played Albert in a major motion picture in 2006. That film, and the media interest it generated, gave massive attention to the lives and motivations of the hangmen and it gave audiences something of the Yorkshire context. After all, most of the famous hangmen have been northerners – most from Lancashire or Yorkshire and speculation on why that is the case has always been popular.

Albert’s time as chief executioner includes such large slices of crime history as the hanging of Ruth Ellis, the traitor Lord Haw Haw, various German spies, the Nuremburg executions, Derek Bentley, John Christie and Timothy Evans. In all he hanged around 433 men and 17 women and served from 1932 to 1956. He died in Southport in 1992, aged eighty-seven. He wrote his autobiography, but we also have two recent works on his life: Steve Fielding’s Pierrepoint: A Family of Executioners and Leonora Klein’s A Very English Hangman.

Albert’s progress towards stepping into the shoes of his father and uncle followed the usual course, writing the letter and then being called for interview at Strangeways. He had looked closely at his father’s notes on the profession and was fully informed when he went to be considered. When he received his letter of acceptance, it came with a list of rules, and the tone of these is very much a sign of a regime ‘under new management’ in the sense that there is a great deal of stipulation of conduct and procedure. Most of the rules are concerned with punctuality and discretion; one of the most telling sections reads: ‘he [the hangman] should avoid attracting public attention in going to or from the prison, and he is forbidden from giving to any person particulars on the subject of his duty for publication.’ The spirit of the rules is in line with the renewed demands for moral probity and sensitivity on the part of the hangmen added to the list.

One man who had recently resigned from the list, Tommy Mann, was still around to advise writers on the Pierrepoints when Klein wrote her life of Albert, and he was one of the select names on the list, only finishing that work because of the demands of his main employment.

For Albert, his first job teamed up with Tom was in Ireland. The two men crossed to Dublin where there was a victim waiting for them at Mountjoy prison. Steve Fielding makes a point that Tom had a revolver and bullets in his belongings before that trip – hardly a feature we might have expected in that trade, but in that instance there had been trouble over in Ireland regarding the killer, Patrick MacDermott, who had been sentenced to die for the murder of his brother. It appears that his motive was to inherit the land where they had a farm, in Roscommon. The journey the hangmen took to Ireland on that occasion was as eventful and tense as anything in a crime novel; they had to make three changes of transport, then take the Holyhead ferry again. As Tom was a good singer, he joined in with a party on the ship, and later there was a gang of people waiting for their arrival in Dun Laoghaire. It was only because a man they had befriended gave them cover and a lift that they escaped trouble. The execution went smoothly, but there was another crowd waiting for them outside the gaol; it seems that Tom was an expert at melting anonymously into a group of people and he did so again, keeping his nephew under his wing. A significant footnote to the adventure (with Harry in mind) is that Tom refused the traditional whisky after the drop, when the corpse was inspected by the doctor and the good job well done celebrated with a drink.

Tom and Albert had another sixteen years in which they acted together from time to time; their joint operations are well documented, but the events which are not so well known are the reprieves. The first case Albert was supposed to watch, simply as an observer, turned out to be cancelled as a reprieve came, and a far more notorious case came along in 1936. This was the story of William Edwards of Bradford. He was sentenced to death for killing his girlfriend but he had severe epilepsy and there was ample evidence of his mental problems to make it a complex case at trial. A highly regarded doctor from Switzerland gave a statement to the effect that there was a case for diminished responsibility for Edwards. He said, ‘From the facts put before me, and the examination I have made of the prisoner, I have arrived at the following conclusion, namely, that it is highly probable that Edwards suffers from occasional attacks of epilepsy.’ He listed frequent headaches, moodiness and loss of temper, a history of attacks of an epileptic nature, and loss of memory.

On the fateful night, Edwards had gone out with his girlfriend and everything had been fine; they had been to the pictures in Bradford. But later, when they met again, he took out his pen-knife and, according to one statement, ‘whirled his arm, not knowing where it fell’. But Edwards had done a similar attack previously. Eventually he was sentenced for murder and was on his way to the Pierrepoints when the reprieve came.

One hanging the two men did do together at Armley was that of David Blake, who had strangled Emily Yeomans in Middleton Woods near Beeston. Emily was a waitress and she lived near Dewsbury Road. The killer went for a heavy drinking session with Albert Schofield (his intended best man) and then went walking with Emily. Blake was hardly discreet in keeping his terrible act quiet; he gave a powder compact belonging to Emily to the wife of a man who had put him up for the night and he made a point of talking about the murder case as reported in the local paper. He was questioned by police and traces of Emily Yeoman’s hair were found on him.

There was a chance that he may have been innocent, as police had arrested a man called Talbot and there was forensic evidence to link him to Emily. But it was Blake who went to the gallows.

In the Second World War, naturally there would be spies rather than murders as clients for the Pierrepoints. At Wandsworth in 1941 they had their first such case when they hanged two Germans who had landed near Banff in Scotland; they were Karl Drucke and Werner Walti. They aroused suspicion by their general behaviour and when accosted and searched, Drucke was found to have a pistol, a radio transmitter – and a German sausage. In July 1942, the first Englishman to be hanged for treason was a client of Tom Pierrepoint at Wandsworth: this was George Armstrong, from Newcastle.

In 1941, on 31 October, Albert Pierrepoint acted as chief executioner for the first time, and his client was an infamous London villain whose case went to the House of Lords. This was Antonio Mancini, known as ‘Babe’. The killing was an ignominious one, simply a fight in relation to the club which Mancini managed, the Balm Beach Club in Soho. Mancini had been threatened after a scrap with a gang of men who he barred, one of whom was Harry Distleman. When they renewed acquaintance in a fight, Mancini had a knife ready. There would obviously be a claim for self-defence on the part of Mancini.

Even though the appeal went to the Lords, the cards were stacked against Mancini; he had a long list of previous convictions for assault and he had carried the knife ready for the encounter. It was at this job, in Pentonville, that Albert met his assistant, Steve Wade. There was no doubt that Albert had learned his trade, as he was already working out the drop when he was asked by a member of staff what might be required. New ropes from the official suppliers were ready, and the hangmen carried out the normal test-drop. This time it was Albert who was the master, with a student, Steve Wade, who was new to the game and needed guidance. They were up at six on the morning of the hanging and Wade prepared the trapdoors. Albert had given close attention to every part of the preparation, all in order to cut seconds off the execution time.

Steve Wade put the cap on Mancini and Albert turned to look at the prisoner; as the noose was put on, Mancini said ‘Cheerio.’ Albert had certainly impressed the prison staff and his speed and efficiency were noted. He and Wade worked very well together, as Albert’s memoirs show.

Royal Commission on Capital Punishment, 1953. HMSO

In Yorkshire, one of Albert’s first tasks was to hang Sidney Delasalle, who had shot Ronald Murphy at the North Country Camp in February, 1944. This was one of those rare cases in which there was a slight possibility of the killer being in a condition of automatism, which, if proved satisfactorily by medical experts, could constitute a defence and a shift from murder to manslaughter.

Delasalle, a soldier at the North Country camp, was in a very bad mood one day when Flight sergeant Murphy and Corporal Taylor came to inspect the beds in Delasalle’s quarters; the man was aggressive and actually challenged Murphy to go outside for a fight. That was the last straw and Murphy put the man on a charge. He did fourteen days of ‘jankers’. When he came out, the revenge was vicious and swift; a line of men were queuing for tea when Delasalle appeared on the scene with a rifle. He shot the man several times and was then overpowered.

Clearly, there was no doubt of his guilt, but at the trial in Leeds a Dr Macadam brought up the subject of the possible automatism that may have applied to Delasalle. This is the defence made when it is demonstrated that a killer was in a trance or sleepwalking when a homicide was committed. If so, in this case Delasalle would genuinely have had no memory of what he had done. It all came to nothing; such a defence is extremely difficult to demonstrate conclusively to a jury of course.

The soldier was hanged at Durham in March, 1944.

Another wartime Yorkshire murder that led to work at the scaffold for Albert (and this time with a new assistant, Herbert Harris) was yet another killing by army men; it took place at the Nags Head at Clayton Heights, Bradford, in September 1944. Arthur Thompson, a soldier, and Thomas Thomson, were regulars at the pub. Arthur had made it plain to his friend that he was desperate for money, and yet one day he went to the Westwood Hospital and paid off some debts to his cronies. He was doing dangerous and risky things, including going AWOL from the army. He went on a crime spree across the Pennines, but he also did the thing that most often ends up with the police at the door: he sold some of the items stolen from Jane Coulton at the Nag’s Head.

What Thompson had done was break into the inn and stolen money and jewellery. It seems as though Jane had been woken up and disturbed him, and she had been strangled in her bed. The forensics showed that specimens of a different blood group from Jane were present in the room at the scene where there had been a struggle in the bed. This was group A and tallied with Thompson’s blood.

The killer was caught trying to sell another piece of jewellery in Overton. The police were called and the man, with false papers on him with the name of Reid, was arrested. Other items stolen from Jane Coulton were found hidden in the police car in which he was taken to be questioned.

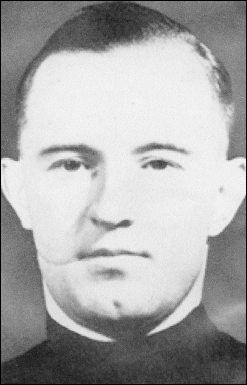

Lord Haw Haw. Author’s collection

Albert Pierrepoint was by that time an expert in his profession; he had been busy with traitors and was soon to be in demand at the trials of Nazis for war crimes. But first we must recall his execution of one of the most notorious traitors in any nation’s history, the so-called Lord Haw Haw, William Joyce. Early in the Second World War, the Nazi regime had established a widespread propaganda network, including the provision of English-speaking staff at radio Berlin. In addition to that, the Germans must have been stunned at their good fortune in having an ex-Blackshirt British fascist, William Joyce, working for them with his nickname of Lord Haw Haw. He had said that he would go to Germany (even before the war began) and ‘throw in his lot’ with them. He was treated with a certain degree of suspicion as he may have been a double agent, of course.

But a man working for Goebbels’ propaganda machine supported Joyce, against the odds, and he was accepted. Soon his broadcasts, beginning with ‘This is Germany calling’ and expressed in a cut-glass accent, were becoming familiar everywhere. He also began writing scripts for other radio outfits which were part of the German initiatives of psychological warfare.

Joyce was born in New York in 1906; his father was Irish and his mother English. At school in Galway he had his nose broken in a fight and that affected his enunciation, giving the nasal quality to his broadcast voice later on; but he was to turn out a fit, athletic man and found an outlet for his aggression and his politic in British fascism. He even led one group of fascists into a confrontation at Lambeth Bath Hall and at that place he was cut along the face and so had a scar – something always prominent in images of him later on.

Naturally, Joyce supported the fascists established under Oswald Mosley and lasted there until 1937, leaving them under a cloud. Under a threat of internment, he crossed to Germany in August 1939. From there his life and work led inevitably into a life as a traitor to Britain, his last broadcast being made from Hamburg in April 1945. He was arrested and charged with treason and sentenced to death, having been caught near the Danish border. He drew a swastika on the wall of the death cell and was without remorse to the end, even when he knew about the concentration camps.

Joyce’s trial at the Old Bailey lasted three days. It was a hard task to demonstrate the offence of treason and in the end, everything depended on the date his British passport expired. As it expired after his first broadcasts, he had committed treasonable offences. He even had his appeal go to the House of Lords. But on 3 January 1946, Albert, assisted by Alex Riley, hanged Lord Haw Haw.

Of course, Albert was very much in demand at the War Crimes trials in Nuremberg. There had been a long period before these trials began, as the great powers and the leaders disagreed at first about the required methods of dealing with Nazis. The crimes were in a range of areas, principally in theft of works of art and, naturally, in the extermination of Jewish peoples and others in their policy of genocide. Churchill at first wanted a select (and large) number of Nazis shot without trial. The American regime considered plans such as converting the whole of Germany into a pastoral economy with no armaments at all. Largely due to the machinations of Stalin and a series of meetings to discuss trials, the long sequence of war crimes trials began and Albert Pierrepoint was to find himself at the centre of a controversy.

Much of this was related to the events developing as part of the retribution given, coming from the understandably deep hatred and vengeance in so many people. George Orwell, in his column ‘As I Please’ on 9 November 1945, wrote, after seeing a man kicking a prostrate German prisoner, ‘I wondered if the Jew was getting any real kick out of this new-found power that he was exercising. I concluded that he wasn’t really enjoying it and that he was merely . . . telling himself that he was enjoying it.’

In other words, when the question of a trial came up, the allied powers had to be careful that they were not as barbaric as the Nazi culprits had been in their phase of power. What happened was that a Royal Warrant allowed for the trial of some of the Belsen camp criminals under the military court system. The men on trial included such notorious Nazis as Kramer, who had been in charge at Birkenau when 200,000 Jews were gassed. This particular trial, of the Belsen Nazis, took over fifty days; at the end, the death sentences were passed, most notably including Josef Kramer, Irma Grese and Juana Bormann. Albert was the man to see these sentences carried out, being flown out there from RAF Northolt to Germany. As biographer Leonora Klein points out, there was a media frenzy at Northolt (so much for secrecy and discretion): ‘For the first time in modern history, the hangman was officially embraced by the British state.’

Waiting in Hameln were thirteen Nazis. Albert was to be housed away from the prison, but he obviously spent time preparing for the job. In his own autobiography he wrote about this, even to the point of the loud and constant sound of the graves being dug outside. The most challenging part of his role, however, was that he had to weight and study each person – not his common practice in his normal work in Britain. He had a translator and spent time with each one, even with the three women who would be his victims. It was highly unusual for Albert. For one thing, he was aware that the people waiting to die would hear the traps slamming near to them as the first Nazis went to their deaths. Albert decided to hang the women first, singly, and then have double executions after that.

The bare statistics of Albert’s work as executioner in the period between the end of December 1945 and October 1948 were that he hanged 226 people, and of these, 191 were Nazi war criminals or other individuals guilty of the capital crime of treason. The controversy was partly to do with something historian Sadkat Kadri notes: ‘The executions themselves were reportedly even more unpleasant than such things are by their nature. Several of the men are said to have had their faces battered by the swinging trapdoor as they fell. Some thrashed around for up to fifteen minutes, suffocating at the end of nooses that had been cut too short to snap their necks.’ That criticism does not apply to Albert Pierrepoint. He would not have allowed such things. In his own memoirs he writes, ‘ I came back to the corridor to pinion Klein, then brought him to the execution chamber . . . I adjusted the ropes and flew to the lever . . . This first double execution took just twenty-five seconds.’

It must have been a bizarre experience for Albert to return to ‘normality’ after that, and to turn up at various English gaols to hang common murderers rather than mass murderers of the Nazi regime. But one of his most significant jobs has a strong Yorkshire connection: the hanging of John Reginald Christie at Pentonville in July 1953. Christie, the beast of 10 Rillington Place, had strangled several women at that address (no longer in existence) and buried them on his property. Christie was born in Boothtown, Halifax, close to the Dean Clough area, and when he moved to London he became a special constable and used his air of authority, along with his supposed medical skills, to lure women to their doom by means of his self-made gassing equipment.

Christie, known in Halifax in his youth as ‘Johnny No-Dick’ clearly had profound sexual problems which had a deleterious effect on his self-esteem and played a major part in the development of his psychopathic tendencies.

A man called Beresford Brown, living near Christie’s lair, found a body when he knocked through a wall. From that point, the hunt was on for the killer, and on 31 March, a police constable walking on the embankment near Putney Bridge, questioned a man hanging about, looking dishevelled; although the man said he was one John Waddington, when he took off his hat, the officer saw that he was the wanted man, Christie. He confessed to the killings, stating that he had used a ligature to strangle his victims.

At the trial in June, 1953, Christie’s defence put up the argument (only to be expected) that the man was guilty but insane. But that plea was dismissed and he was found guilty of murder. Naturally, with such a notorious client, there was a massive crowd gathered at Pentonville to be present at the momentous time when the ‘beast of Rillington Place’ would meet his doom. Harry Smith was assisting Albert that day, and as they passed a window from where they could see the crowd Albert said, ‘I suppose that’s the sort of lot who watched hangings at Tyburn, with blokes selling sweets and hot rum to the crowd!’

Christie went to his death with a sneer on his face; as the hood was slipped on, Albert sensed something, and this, as he explained later, was that ‘It was more than terror . . . at that moment I know that Christie would have given anything in his power to postpone his own death.’ Christie was close to fainting when Albert moved sharply to send him away, from the trap into eternity.

Albert’s last Yorkshire appointment was to despatch a soldier, Philip Henry, who had raped and murdered Flora Gilligan at York in March 1953. This was a particularly repulsive crime; the victim was seventy-six years of age. Henry, who was due to go on active service abroad the next day, was nailed by forensic work, some splinters of wood being found on him, and these matched the wood on the window frame at the house in Diamond Street, York, where the crime was committed. There was also a matching fingerprint found, so Henry had little hope of acquittal and indeed at the trial, after a request by the jury to visit the scene of crime, he was found guilty of murder. Albert stepped into work at Armley, the place where Steve Wade normally worked, to hang Henry.

The Pierrepoint dynasty of hangmen undoubtedly created a great deal of professionalism and pride in their work; Albert is the one from the family whose career has had the most prominence in the media and in biography, and one aspect of that long career that needs to be stressed is that he withstood a huge amount of pressure in all kinds of contexts, from the war crimes work to his responses give to commissions on capital punishment. On top of that he had to carry on acting with restraint, discretion and self-respect when the work he did was repeatedly questioned as attitudes changed. Certainly after the hanging of Ruth Ellis and then with the growing understanding that Timothy Evans had been hanged for a crime he did not commit (his wife having been killed by Christie) there was cause for self-examination and reflection. He had shown the Prison Commission that he could keep up the requirement to show ‘complete reticence’ as their handbook put it in the 1930s.

Albert’s resignation came with a dispute about fees. After the execution of a man called Bancroft in Manchester, Albert wrote to the Commissioners, after the man had been reprieved: ‘On returning home I was only paid my out of pocket travelling expenses’. Then, nothing being settled to his satisfaction, he wrote on 23 February 1956: ‘In the circumstances I have made up my mind to resign and this letter must be accepted as a letter of resignation. I request the removal of my name from the list of executioners forthwith.’

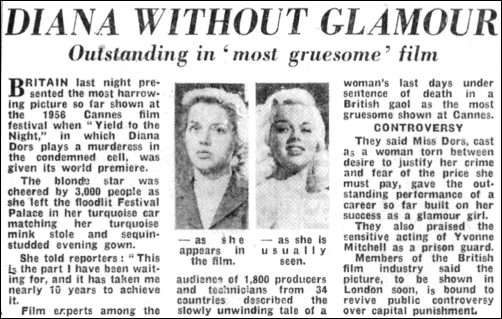

Feature on ‘Yield to the Night’ – on a murderess in the condemned cell. Scunthorpe Evening Telegraph

Albert died on the 10 July 1992, in a nursing home. His former assistant, Steve Wade, had retired through ill health in October 1955 just before Albert’s last year in office. Just a year after Albert’s resignation, the 1957 Homicide Act, introduced by Sidney Silverman, passed in the Commons, but as Charles Duff put it in his book, A Handbook on Hanging, it got ‘short shrift when it went to the House of Lords but there is a deep irony in the fact that hanging was ‘suspended’ for the whole of 1956. But the man he trained learned well. Wade, from Doncaster, was to have a short period in office, but had some tough trials of nerve and strength.

Steve Wade comes down to us from one photograph; our image of him is of a man with a drink and a cigarette, the face suggesting someone under pressure, maybe a nervous type. That is not associated with a hangman, of course. What the image does convey is that he was maybe ill when the picture was done. He was not in office long – from 1941 to 1955 – and had to retire through ill health. He died in 1959, having been assistant to both Tom and Albert Pierrepoint. Steve handled twenty-nine hangings as chief executioner, and he had some really difficult cases.

Steve Wade. Laura Carter

He once said that he ‘carried out more executions than I could remember’ and that suggests a man who was not necessarily meticulous. He also pointed out that the hanging was a sideline. Indeed it was, because he was in the transport business in Doncaster. If a full biography of him was ever written, the subtitle might read, ‘Executioner and bus owner.’ When he wrote to the Home Office to offer his services, he was at first refused as he was so young, but Wade must have been determined because he wrote again later and then was accepted. He was placed on a waiting list and given the usual course of instruction, before being appointed deputy to Thomas Pierrepoint.

Wade went to live in Doncaster in 1935 and he established his coaching business in the Waterdale area. He must have had a sense of humour (very dark) because, according to Brian Bailey, Wade tricked Albert Pierrepoint into thinking that both he and Wade were needed to be at the post-mortem of a young man from Burma who had murdered his wife, after they had executed the man. The pathologist involved was the famous Keith Simpson. According to Molly Lefebure, who was Simpson’s secretary at the time, Pierrepoint walked into the set-up scene and said, ‘If you don’t mind, I’d like to take a look at my handiwork.’ That hardly seems in keeping with the man, and if he did, he would have seen a fracture dislocation between the second and third cervical vertebrae. Bailey makes the point that such a detail signifies the quickest and ‘cleanest’ death for a victim of the hangman’s art.

Wade’s first job as assistant was with Tom Pierrepoint at Wandsworth, where they hanged George Armstrong, a man who spied for Germany, starting that work after contacting a German consul in the USA. He was tried at the Old Bailey, then appealed and after that failed, found himself facing the noose.

But before Steve Wade began his main work in Yorkshire, he had a job with Albert hanging another spy that turned out to be a terrible ordeal. Wade took a few notes on jobs, and a typical one is this one on William Cooper at Bedford in 1940. Tom and Albert were the official hangmen, but Wade must have been there to observe and to learn, because he made these notes:

William Henry Cooper at Bedford, aged 24. Height, five feet five and a half inches. Weight 136lbs. Drop 8feet one inch. Assisted to Scaffold. Hanged 9 a.m. on Nov. 26 1940.

He notes that the personnel present were ‘Pierrepoint, Wade and Allen’ but that does not tally with the official record.

As time went on he wrote more, as in the case of Mancini for which he wrote ‘Three appeals with the House of Lords.’ But the ordeal was to come with the execution of the spy Karel Richter. Richter’s records have now been released and we know that his mission was to deliver funds and a spare wireless crystal to another spy. He was given a code and money and also a supply of secret ink and was even briefed on what to say if interrogated. Acccording to some opinions, his arrival on espionage work was part of a ‘double-cross ‘ system which meant that agents were captured and given an option either to work as double agents or to face the gallows.

Richter was parachuted into Hertfordshire in 1941 and it appears that Churchill wanted him executed, as other agents had landed and not been hanged. That might be arguable, but what happened, according to MI5, is that Richter landed on the 14 May and that war reserve constable Boott at London Colney saw a lorry driver talking to a man who turned out to be the spy. Sergeant Palmer of St Albans was informed and came to assist. Richter was taken to Fleetville Police Station and there he showed a Czech passport. When searched he had a ration book, a compass, cash and a map of East Anglia.

Richter was seen by a girl, Florrie Cowley (nee Chapman) who recalls going to visit her divisional campsite, of the guides, at Colney heath and that she and a friend went into a storage hut. There they saw evidence of very recent occupation. She wrote in a memoir,

‘We quickly came out to think the situation over. Being war time there were no vagabonds, tramps etc around so who could be living there? We then thought a German spy could have dropped . . .’ They were right. Photographs survive of Richter going back to the field with army and police to find his buried equipment. Richter stands in one photograph, pointing, while surrounded by personnel. He was destined to be Pierrepoint and Wade’s client on 10 December 1941.

Wade kept notes on what happened that day. It was a horrendous experience for the young hangman, so early in his career. First he wrote, ‘Karl Richter, 29, five feet and eleven and a half inches. 172 lbs. Execution: good under the circumstances’ That has to be one of the greatest understatements ever written. Richter was athletic, strong and determined to cause the maximum resistance when the hangmen arrived at the death-cell. Wade wrote:

On entering cell to take prisoner over and pinion him he made a bolt towards the door. I warded him off and he then charged the wall at a terrific force with his head. This made him most violent. We seized him and strapped his arms at rear . . . The belt was faulty, not enough eyelid holes, and he broke away from them. I shouted to Albert ‘He is loose’ and he was held by warders until we made him secure. He could not take it and charged again for the wall screaming HELP ME.

Things were still very difficult, as the man then had to be manhandled by several warders. Even at the scaffold, Richter fought:

. . . he then tried to get to the opposite wall over trap. Legs splayed. I drew them together and see Albert going to the lever. I shout wait, strap on legs and down he goes. As rope was fixed around his neck he shook his head and the safety ring, too big, slips . . .

Wade’s notes have a tone of relief as he writes finally, ‘Neck broken immediately.’

At the end of his notes he wrote that he said something to Albert, a comment along the lines of ‘I would not miss this for fifty pounds . . .’

Richter actually stated under questioning that he had declined to take a part in the ‘double cross system’. He had been a marine engineer and had a child in the USA. He was interned and returned to Germany after trying to return to America. In Germany he was recruited by the Abwehr (the German intelligence and counter intelligence organisation). Nigel West, in his history of MI5, has a coda to add to Steve Wade’s terrible memoir:

The grisly scene had a profound effect on all those present, and, indirectly, on some other Abwehr agents. Several months later Pierrepoint and his chief assistant, Steve Wade, carried out an execution at Mountjoy in Dublin. News of Richter’s final moments reached Gunther Schutz and his fellow internees . . . Irish warders gleefully recounted the details of the struggle on the scaffold, sending Richter’s former colleagues into a deep depression.

Moorfield Street, Halifax, where McEwen’s victim, Turner, lived. The author

In the war years, Wade was also on duty to hang a Canadian soldier who had committed a terrible murder of an old man in Halifax. Mervin McEwen was on the loose, camping out on the large area of Savile Park in Halifax when he befriended Mark Turner, aged eighty-two. Mr Turner lived on Moorfield Street, very close to the park, and he invited McEwen and another man to have a drink at his home. The soldier went back to his hut on the park after that, but Turner was found battered to death on his settee the next morning and McEwen was nowhere to be found. But the killer had been very careless: there were fingerprints found on a whisky bottle and also battledress and badges from McEwen’s regiment, the Royal Canadian Corps. Not surprisingly, there was no sign of the killer. He had run away to Manchester and was about to start a new life with a new identity and a partner, a woman called Annie Perfect. He was then known as James Acton. He must have thought that he had a bolt-hole and was surely beyond being traced, but he was wrong.

Something happened that reinforces the view that steady, methodical police work pays dividends, and that even the craftiest villains fall foul of their own arrogance. The Canadian dropped his guard and did something so foolish, it seems amazing that he was caught so easily.

A constable arrived at his new house, simply making routine enquiries, but when he explained who he was, McEwen produced an identity card with the name Mark Turney on it. The officer was smart and suspicious, so he asked for a signature. He had seen that the letter ‘r’ had been changed to a ‘y’ and there was something amiss. The change had been done clumsily so it was easily noticed. Amazingly, McEwen signed as Mervin Turney. The game was up.

The killer saw that any attempt to lie his way out of the situation was futile and he gave himself up. His story was that he had indeed gone back to the old man’s house in Halifax, cooked some food and drunk some whisky. In this state, he struck Turner as he woke up, claiming that it was not intentional. His main line of thought was that he was intoxicated and could not have planned murder. He failed, and in forty minutes, the jury at Leeds found him guilty of murder. Tom Pierrepoint and Wade hanged him at Armley on 3 February 1944.

From 1947, Wade did several hangings in Leeds, beginning with Albert Sabin from Morley, who murdered Dr Neil Macleod at Topcliffe Pit Lane in Morley in 1947. Sabin had been seen running and getting into the doctor’s car in the early afternoon of 21 September 1946. Sabin was just twenty-one, and in his army uniform. At around half past two that same day a shot was heard in the lane.

The doctor was found dead only a short time after his murder, by Harry Philpott as he was walking near to the Topcliffe pit. The scene was like one of Hitchcock’s more macabre episodes, as poor Harry followed a trail of blood, then a knife and finally a gun. Then there was the body of MacLeod in a hollow, having been shot three times as it turned out.

The hunt was on for the doctor’s car, a Ford V8. It was not a difficult task in those naïve days when occasional, opportunist criminals (unlike the professionals of course) merely took their victim’s property and did not think too much about forward planning. Sabin was found in Pudsey, where his car was parked, and arrested. There was also no question of any mindgames or ploys to buy time and cause trouble: Sabin simply confessed to the killing when accosted.

The issue was whether or not this was a murder; but it was ascertained that Sabin took the gun with him when he went to meet the doctor, and that he had at least an intention to rob, and most likely to do grievous bodily harm if resisted. Taking the victim’s life was merely one more step away from that, with a related intention of ‘malice aforethought’. The only further complication came later when the killer tried to say that the doctor had made sexual advances to him; there were semen stains found on clothing, but they could have occurred just as naturally as part of the shock of death as much as in a sexual encounter, so nothing was conclusive there. Sabin claimed that on the day of the murder, Macleod had said he would give Sabin a lift back to camp, but then had driven to a place where he could make his advances. Naturally, Sabin tried to construct a narrative which culminated in a struggle and consequently that the gun had fired with no intention on Sabin’s part to take life. That story did not convince the jury and Steve Wade, along with Harry Kirk, had a client at Armley – just twenty-one and a hardened killer – waiting for them in the death cell in January 1947.

The team of Wade and Kirk were busy in the summer of that year at Leeds. Wade and Kirk did three hangings by the end of 1949 and Wade had another assistant for yet another Leeds execution in that eighteen months. Wade’s victims were from that area of life we might call domestic-tragic. Their killings were of women, either known to them or prostitutes. The men waiting for the noose at Armley were invariably killers driven by sexual passion, or aggression while drunk, or of course, a combination of all these. Typical was the case of the sad murder of Edith Simmonite in Sheffield. Edith spent a night enjoying a few drinks in the Sun Inn and she had been in company with two men who lived at a nearby hostel – William Smedley being one of them. On the night on which someone murdered Edith, Smedley’s bed at West bar had not been slept in. There were sound testimonies to that fact later.

So when Edith’s body was found, strangled and after having sex, it was a case of basic police work to find out who she had been with and where she had spent her time that day. The task was made even more straightforward by the fact that she was known to the police as a local prostitute. When questioned, Smedley clearly relied on the man with him to back him up in a lie – that the two men had parted from the woman that night and seen her go into her room. Smedley’s tale was not verified by his companion, and so the option open to him then was to invent another suspect. He did this by inventing ‘an Irishman’ who had ostensibly been in Edith’s company. He even claimed that the mysterious Irishman had confessed to the murder to him (Smedley). Smedley had been interviewed twice, and told a plausible tale, so was released on both occasions.

What was also very disturbing and seedy about this case was that Edith’s body was found by a young boy. Peter Johnson was out looking for wood in the old buildings in the areas of the city that had received bomb damage when he found the body. He said, ‘I looked through the doorway and saw a woman lying face downwards at one end of the room. I ran and fetched Ronnie [his friend] . . . and then we went to tell a bus man.’ Edith was only twenty-seven, and she also had been living in a women’s hostel in the same West Bar area. Her hostel landlord had not seen her since the Friday, and her body was found on Sunday.

The man must have been at least partially convincing, because he claimed the killer had gone to Rhyl and the police gave Smedley the benefit of the doubt, going with him to Rhyl to try to find the killer. Nothing came of that. Not long after, Smedley told the truth to his sister.

The killer had one more story to tell in order to try to create some kind of desperate extenuating circumstances around the vicious murder. He said that he had had sex with Edith but then she had told him that she had a venereal disease, so this information prompted him to attack her, and he lost control in his rage.

None of this achieved anything that would save him from the scaffold; he was hanged by the Wade-Kirk duo in August 1947. Smedley had been told that he had no chance of an appeal, but in sheer desperation he tried the last ploy – a letter to the Home Secretary asking for a pardon. As Sheffield writer, David Bentley, has written in his book The Sheffield Hanged, ‘The execution attracted no interest, not a single person being present when the statutory notices were posted outside.’

A hanging at Leeds in March 1950 was one of those cases that once again highlighted the complex moral and legal issues around the execution of young people. Two young men, Walter Sharpe and Gordon Lannen robbed a jeweller’s shop in Albion Street and the jeweller decided to fight them. In the struggle, Abraham Levine, forty-nine, was battered during this attempt to save his goods from being stolen by force. He was cracked with a gun butt and still would not let go his hold on one of the robbers. Then two shots were fired and Levine was mortally wounded.

Sharpe was twenty and Lannen only seventeen. They had some imaginative notions, perhaps from gangster films, because they fired their guns into the air as they ran away. Both had firearms and the most tragic footnote to the story is that they went away with no stolen goods at all. Their victim died the next day.

Simple ballistic analysis linked the bullets in Leeds to bullets fired at a robbery in Southport and the villains were tracked down. Under questioning, it emerged that Sharpe had fired the fatal shots. As in hundreds of similar cases, the defence was naturally that the gun went off in the struggle, and that defence failed. They had robbed before, while armed, and they had been reckless outside as well as in the premises.

In court matters were straightforward: as a crime was being committed, firearms were discharged: it was murder. Of course, that led to the inevitable conclusion: the elder man to be hanged and the younger, teenager, to be a guest of His Majesty for a very long time. Their choice of Albion Street, right at the very heart of the shopping centre of Leeds then as now, meant that they were firing guns in the vicinity of passers-by, citizens of all ages, going about their daily business.

But of course, the old discussions came back: there were only three years difference in the two young men, yet the older one was to hang. On the other hand, the older one had fired the gun that killed the victim. The 1908 Act had banned the execution of persons under sixteen, and in 1938 that age was raised to eighteen, after some high profile cases led to prolonged debate.

Walter Sharpe was hanged at Armley on 30 March 1950. Wade and Harry Allen officiated.

Towards the end of his short period in office, Wade had two victims both called Moore. The first, Alfred Moore, was guilty of killing two police officers and so his story made all the papers and provoked those elements of society in favour of retaining the death penalty to insist that for the murder of police officers, hanging should always be the sentence. In the 1957 Homicide Act, there were five definite instances in which hanging should be applied and one was ‘Any murder of a police officer acting in the execution of his duty or of a person assisting a police officer so acting.’ Moore’s killing had done much to put that sentence there.

The double murder took place in the most unlikely of places: the quiet suburb of Huddersfeld, Kirkheaton, at Whinney Close Farm. Even today, this is an area in which older property with ample gardens stand side by side with newer suburban developments, quiet, occupied by families, and on the edge of the town, not far from the fields and smallholdings around Lepton.

In July 1951 Alfred Moore was a smallholder there, keeping poultry. But he also had a sideline in burglary to earn some extra cash. He was evidently not very skilled in his criminal activities and the police soon had him marked for observation. On 15 July the police surrounded his little homestead with the intention of catching him with stolen goods on him or on his property.

It was a stake-out that went badly wrong. In that very peaceful early morning of the Sunday, shots were fired in Kirkheaton and as officers moved around in the dark, trying to communicate and find the source of the gunfire, it was discovered that two officers had been shot: Duncan Fraser, a detective inspector, was found dead, and P C Jagger was severely wounded.

It was learned that Moore was holed up inside his house and it was inevitable that he would eventually be captured. The only glitch in the investigation was that, as a revolver had been used in the killings, a revolver had to be found on the person or the property and that never happened. Moore had a shotgun. But despite the use of a metal-detector, a revolver was never located.

But of course, P C Jagger was still alive so there was a witness to the dreadful events of that early morning. From his hospital bed, Jagger picked out Moore from a line-up. In a stunning piece of bravery and high drama, a specially formed court was formed at the hospital so that Jagger, almost certainly dying, could testify. Moore was tried for murder in Leeds; P C Jagger died just the day after giving evidence. Wade and Allen were busy at Armley once again.

The other Moore was a partner in a car sales company, along with Tom Bramley. They naturally met with other car dealers and one of these was Edward Watson. This terrible tale began with the sale of a faulty vehicle to Moore, sold by Watson at a cost of £55 (in 1954 a large sum). That transaction was to lead to a murder at the darkly fated area of Fewston, near the reservoir in Swaledale, where two more murders had occurred.

It was when the car was sold back to Watson at a loss that trouble started brewing. Moore wanted to get his own back after the dodgy deal. Moore arranged to meet and then drive his enemy to Harrogate to see a vehicle. That was the black beginning of a brutal plan, because Moore had a rifle fitted with a silencer for that journey. He had been careless, though, because he had a spade in the back of his car and that was noticed by others; later that would be very much against him.

Harrogate is only around eight miles from Fewston, along the scenic road towards Blubberhouses (going along the dale finally to Skipton) and in fact Moore had shot his victim five times and then driven out to the desolate spot to bury him. Mrs Watson was obviously worried about her husband’s disappearance and police questioned Moore, who claimed that Watson had never turned up for their meeting and jaunt to Harrogate. People knew about both the rifle and the spade, and an officer called Wilby persisted with his questioning of the dealer.

The killer boldly said to the officer, ‘You don’t think I’ve shot and killed him do you?’

That was a neat summary of the actual events. Moore grew desperate and he actually tried to take his own life, but then he caved in and confessed, beginning to formulate a tall tale about a fight with the gun and an accidental death. There were lots of anomalies in statements made – things that did not sit easily with the forensic evidence. In court, it became clear that this was a case of murder and Moore was sentenced to hang.

Wade’s last hanging was a more mundane case: simply a case of a man killing his wife’s mother – the woman who had stood in the way, as he saw it, of his happiness with Maureen Farrell of Wombwell. Her mother, Clara, became an object of hatred for the young man, Alec Wilkinson, only twenty-two years old. On 1 May 1955, Wilkinson had a great deal to drink and worked himself up to a mood of extreme violence and enmity towards Clara Farrell.

Not long after their marriage, Alec and Maureen had been under pressure, and the relationship between Alec and his mother-in-law was one of extreme emotional tension, she was apparently always criticising him and making it clear that he was worthless (at least that is how he claimed to see the situation). On the fateful day when he walked up to the front door of the Farrell’s home in Wombwell, he had a burning spite in him and he was in a mood to use it. First he sprang on Clara and punched her and then slammed her head on the floor.

But such was the man’s fury that he went for a knife in the kitchen, stabbed her, and then did something that suggests a psychosis as well as a drunken fit: he piled furniture on the woman and set fire to it. Wilkinson left as someone came to try to put out the fire, but later Alec confessed and one of his statements was that he was not sorry for what he had done. There was an attempt to demonstrate provocation, and even a petition to save him, but Wilkinson was found guilty of murder at Sheffield and sentenced to hang. This time, on Wade’s last appearance as hangman, when he was becoming too ill to do any more, his assistant was Robert Stewart.

Steve Wade returned to Doncaster and lived on Thorne Road, Edenthorpe. He had been a café proprietor and he operated Wade’s Motor Coaches. He retired in 1955 and died just over a year after hanging Wilkinson, on 22 December 1956, at Doncaster Royal Infirmary. The only teasing question about his official obituary is this note: ‘Buried at Rosehill Cemetery (unconsecrated) in Doncaster.’ He seems to have been a very reticent character. Syd Dernley, who worked with him, said simply, ‘Wade was a quiet man and said no more than hello when Kirky did the introductions.’

Perhaps the laconic Albert Pierrepoint said the simplest and best thing about Steve Wade, in his autobiography, Executioner: Pierrepoint. When being questioned about his work, he was asked, ‘Do you know whether any of those who are at present on the list [the official Home Office list of hangmen] have ever carried out an execution?’

Pierrepoint replied, ‘Only one, and he has done five or six. Steve Wade, a good, reliable man.’

All the chief executioners began as assistants after the turn of the nineteenth century. The new ‘health and safety’ mentality took over and a probationary period was seen as essential. There was no place for the prurient or the sadistic dreamers who formerly applied. Before the new attitudes it had been a case of learning by doing. Marwood was unusual, practising drops with sacks in his home village of Horncastle. Others before the more organised years would not be too concerned about standards and wanted the pay, and of course plenty of drink to steel them to the task in hand.

In the twentieth century it became essential for a new man on the Home Office list to learn by observation and to be properly instructed in all the elements of the job, including appropriate behaviour and tact. We do not have many memoirs of hangmen generally and some of those in print are not very helpful. John Ellis did talk to a ‘ghost writer’ and there are books by Pierrepoint and by Dernley. But the other assistants are shadowy figures. We sometimes have just a few bare facts about them. The main website source for hangmen lists twenty-one men who worked as assistants in the twentieth century. Of these, four worked in Yorkshire from time to time, but undoubtedly Dernley and Allen have the most interest in terms of Yorkshire-based cases. In the late Victorian period, Thomas Henry Scott of Mold Green, Huddersfield was on the list from 1892 to 1901 and at times was the main executioner. We know that Scott assisted Berry but little else has come down to us. There is one anecdote of Scott, though. When he was working in Ireland (in Londonderry) he was the target of a wild mob who threw rotten vegetables at him as he travelled in a cab to the prison. It seems he was also robbed on one occasion in Liverpool; Steve Fielding tells the tale:

On arriving at Lime Street station, he shared a taxi with a young woman of questionable virtue, Winifred Webb, and instead of heading directly for the gaol they chose to cruise around the city for a while. On reaching his destination and after bidding farewell to his companion, Scott discovered that he had been robbed of two pounds, nine and sixpence and a pair of spectacles.

When Scott stepped into the police station to report that, there was the woman, claiming she had been robbed; she was arrested and of course, it was embarrassing for the hangman, who should have stuck to routine and gone straight to Walton gaol.

In Syd Dernley we have a hangman who basked in the notoriety of his trade and was always happy to explain the dark and disturbing secrets of the neck-stetcher’s mystery.

Syd Dernley. Laura Carter

Dernley wrote a chatty, darkly humorous autobiography of his life as a hangman, from his first interview in Lincoln to his last memories of working with the more famous characters. In later life he showed a macabre interest in the trappings of his trade and was only too pleased to regale the media with his tales.

When Dernley was interviewed in 1994 he was happy to pose for the camera with his ropes dangled in front of him. It was noted then that he had been in office from 1949 to 1954 and that he was ‘never given an official reason’ for that removal. Syd was from North Nottinghamshire, living in Mansfield when interviewed, and he was patently pleased to show off his equipment and mementos to the interviewer. He displayed his case, with a hood inside, a legstrap, armstrap and a replica noose. The interviewer noted that Syd enjoyed ‘gallows humour’.

Dernley even used to have a full-sized working gallows when he ran a shop in Mansfield, something taken from a prison in Liverpool; he noted that he had to sell them. He gave a similar reason to Harry Pierrepoint when asked why he had done the work: ‘It was not that I wanted to kill people, but it was the story of travel and adventure, of seeing notorious criminals and meeting famous detectives.’ But the usual moral complexities arose in the interview when he was asked about the hanging of Timothy Evans, clearly as it turned out, innocent of the murder of his wife. Dernley said, ‘Well, if I helped to kill an innocent man as you seem to be implying, it doesn’t worry me one little bit. I did the job I was trained to do, and I did it well.’

Dernley’s most interesting Yorkshire connection was, oddly, with a man hanged at Strangeways. Nicholas Crosby had killed Ruth Massey at Springfield Road in Leeds in July 1950. He had cut her throat after taking her home following a night drinking in the Brougham Arms.

Crosby had given a story of what he had done to his sister, confessing to the murder, but then changed the tale for the police. He claimed that there had been another man and that he heard a scream after walking away, leaving Ruth and the stranger together. His reply to a direct question about whether he killed the woman or not was ‘To be sure sir, I don’t know if I did . . . if I did, I don’t remember.’ He was found guilty of murder and because some execution chambers were being modernised at Armley, Crosby was sent to Strangeways to die. Dernley described the man: ‘Crosby was a twenty-two-year-old gypsy . . . he was to give any number of versions as to what happened.’

Dernley worked with Albert Pierrepoint for the job. What became remarkable about this was that, as Dernley recalled, a man came along to Pierrepoint’s pub, Help the Poor Struggler (in Manchester) with the intention of bribing the hangmen so he could get a picture of a hanging. The man said, ‘Look, I’ve got a business proposition to make to you.’ He wanted to get a camera into the whole process.

When Dernley told him it was impossible, the man said, ‘No, it’s not, we will supply you with a miniature camera, a tiny thing. It’s so small you’ll be able to wear it on your shirt and it’ll be hidden behind your tie until the moment he goes down . . .’ Of course, Dernley refused.

One thing we have from Syd Dernley is detailed accounts of the events at his executions. In Crosby’s case, he writes well of such things, as in his account of entering the death cell: ‘As it turned out, we were right to be worried about Crosby. He was scared out of his wits and when we entered the condemned cell I think he came very, very close to breakdown and hysteria . . .’ The killer asked for the straps not to be tied too tightly, so Dernley and Albert made sure that there were warders ready to intervene if anything devious was planned. As Dernley wrote, ‘Crosby was down and dead in a split second.’ He then notes that two assistants had come along to watch and learn – Doncaster man Harry Smith and Robert Stewart. Dernley commented, ‘ . . . poor Smith and Stewart! In the corridor they must have heard all the commotion without being able to see what the hell was going on. One look at their faces was enough to tell that it had been quite unnerving . . . not a good job for their first experience of executions.’