Calcraft: Celebrity Executioner

ith William Calcraft we begin to encounter the first character who really saw the possibilities of the job with regard to being a public personality. He was born in Essex in 1800, near Chelmsford, and became hangman for London and Middlesex from 1829 to 1874. Although there are some blots on his record, on the whole he was professional. He was the man who hanged some truly notorious criminals in all kinds of major Victorian murder cases, including the Courvoisier murder and the immensely high-profile Norfolk murderer, James Blomfield Rush.

ith William Calcraft we begin to encounter the first character who really saw the possibilities of the job with regard to being a public personality. He was born in Essex in 1800, near Chelmsford, and became hangman for London and Middlesex from 1829 to 1874. Although there are some blots on his record, on the whole he was professional. He was the man who hanged some truly notorious criminals in all kinds of major Victorian murder cases, including the Courvoisier murder and the immensely high-profile Norfolk murderer, James Blomfield Rush.

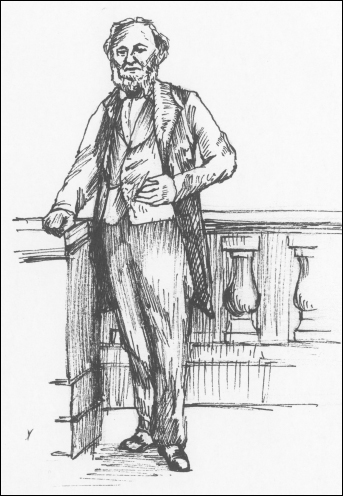

William Calcraft. Laura Carter

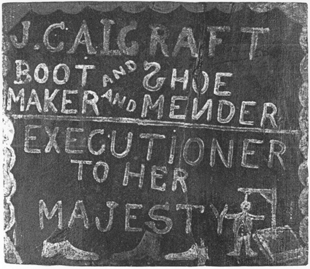

Calcraft’s trade sign. Author’s collection

Calcraft was from a poor family with twelve children. William was talented and did well at school. When he reached adulthood he was strong and robust, starting out in domestic service, but with an eye for business, he saw that the crowds at hangings would provide a good market for anyone selling food, so he began as a trader in snacks for such occasions. But he obviously saw the executioners at work and eventually realised that he could do the work. An opening came at Lincoln, where he worked as assistant, and then he saw a hangman called Foxton at work and befriended him, bringing him a drink after a hard day’s hanging.

Calcraft provided an oral history of his life in old age, and told a number of anecdotes about his entering the craft. Foxton told him all about the job, saying it was ‘a miserable calling, a wretched, despicable occupation’ but that did not deter him. What sums up Calcraft’s attitude was his statement to Foxton that he was open to anything that brought something in to support him and his wife. ‘You are a rum ‘un wanting to take up my line of business’ said Foxton. Calcraft was certainly a puzzling character, but he took to the hanging art very well. Luckily for Calcraft, the deputy hangman, who would have taken over the job on Foxton’s retirement, was seventy years old. Calcraft put in his letter of application. In general, these documents make fascinating reading, as hangmen throughout history have had all kinds of reasons for wanting to do such an unpleasant line of work. Calcraft wrote, ‘Gentlemen, having been informed that the office of executioner will soon be vacant, I beg very humbly to offer myself as a candidate. I am twenty-nine years of age, strong and robust, and have had some experience in the office. I am familiar with the mode of operation, having had, some months ago, been engaged in an emergency to execute two men at Lincoln. I did so, and as the two culprits passed off without a struggle, the execution was performed to the entire satisfaction of the sheriff of the County.’

The hanging in question is interesting. The records show that at Lincoln in 1829 Thomas Lister was hanged for burglary and George Wingfield for highway robbery. The whole business was very irregular. Wingfield’s attack was brutal in the extreme, and he was a Lincoln man, so he was not hanged at the Castle, but on a temporary gallows in the lower city, probably as a warning to citizens not to transgress. This was done at the sessions house yard. Lister, who was a huge man over six feet tall and weighing fifteen stones, was hanged on the same day after eating a pound and a half of beefsteak. He was hanged at eleven-thirty and Wingfield at one in the afternoon. There is some confusion as to whether or not Calcraft was there because 1828 was the year given for his work at Lincoln, and there were no hangings that year. He must have officiated then, and the account says that ‘the Newgate hangman was sent for’. It seems that the man in question was old Mr Cheshire, who would have succeed Foxton had he not been so aged. The Lincoln executions were on 27 March, and Calcraft was appointed on 4 April, so some record somewhere is wrong, unless Calcraft went with old Cheshire and did more than simple standing by. He may have learned to pinion and to place the hood over the heads at Lincoln. He certainly had the confidence behind that letter of application - the tone of a man who is sure that, having had a ‘taster’, he could indeed do the work.

There was a competitor - an ex-soldier called Smith - but he had no experience, so that surely swung the decision in Calcraft’s favour. Calcraft also had to perform some floggings on taking up the appointment - it was not all ropes and pinions. In the 1820s, whippings were administered for a range of offences and sentences often meant that 24 to 36 lashes were ordered. Again, we have his own words on this. He said that when he arrived in the flogging yard he was ‘a little nervous, being afraid I might make some mistake: four young ruffians had to undergo the punishment. The mode of operation had been explained to me by the prison officials and I got through the task in a way that seemed to be altogether satisfactory to those who were present . . .’

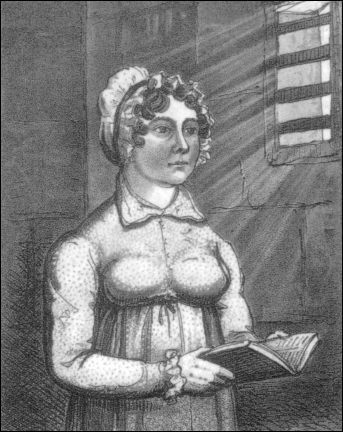

Another of Calcraft’s clients, Elizabeth Fenning. Author’s collection

Calcraft was beginning to make a lot of money in his job. He was paid for the floggings and the hangings, and also he was a shoemaker, and he was living at the time in Devizes Street, Islington with his wife, Louisa. He soon became the professional hangman who could be called anywhere across the land, and he also kept up his hobbies of fishing and rearing animals. He also loved gardening, and altogether, this image of the countryman who happened to have a steady job as hangman made all his work part of a comfortable, fulfilling lifestyle. He was even known to walk to a hanging hand in hand with his little daughter. He was keen to acquire his own set of tools for the trade, and he bought his ropes himself.

It was not long before some of the major felons of the age came his way as clients for the drop. He gave a lot of thought to administering quick deaths, such as tugging on legs and jumping on the backs of swinging criminals, fighting to breathe as they were strangled. He even came up with his own gear for improving on pinioning: ‘The old pinions used to hurt the fellows so. This waist strap fits every person and is not the least uncomfortable.’ This was a special harness he made with a leather belt attached and several buckles. His trade was becoming even more theatrical the more the crowds came to see the deaths. In 1866 black curtains were attached to the scaffold so that there was some element of privacy in what had always been a totally open, public scene of anguish.

Generally, several important personages at the time thought Calcraft to be possessed of that rare professional distance required in such an unsavoury job; he was detached and cold. He had learned to turn off any emotional contact he might have felt with the condemned - and we have to recall that early in his career he was hanging young people and women fairly often. His youngest victim was a nine-year-old boy who had been convicted for arson, though it has to be said that executions of children were very rare. Most were transported up to the 1850s. One journalist said of him: ‘He took the business businesslike.’ One witness to Calcraft at work wrote: ‘ . . . the oddest thing of all was to see Calcraft take the pinioned, fin-like hand of the prisoner and shake it, when he had drawn the white cap over the face and arranged the rope.’

One of the strangest episodes in his life was when he himself was in court - being tried for failing to support his mother. Sarah Calcraft, over seventy in 1850, was in the Witham Union Workhouse in Hatfield Peveril. Calcraft found himself standing in the dock at Worship Street Police Court, answering the charges. The overseers had taken proceedings against Calcraft for funding to maintain the old lady. At first, evidence of Calcraft’s income was not produced so it was adjourned, but when it convened again, there were witnesses testifying on Calcraft’s income. Sarah’s story came out in print in The Times. She had been in desperate circumstances for some time, living with her daughter. Another son was simply a wastrel, a feckless drifter, and so it fell upon William to take the brunt of the accusations of neglect. Calcraft was ordered to pay three shillings a week, and he claimed that such a sum was beyond his capabilities. Sarah died five years later, after being supported by William.

William Calcraft’s name became familiar to the public because of his hanging the villains in some large-scale killings. The Courvoisier case was certainly in that category. Lord William Russell had been found dead on 6 May in his own home; when discovered, the staff found that the room suggested an attack by a burglar who ransacked the place after killing his Lordship. This was something that deeply disturbed Victorian high society - an aristocrat murdered in his own home. The killer was found out by some persistent detective work; a search of his room located a stash of stolen jewels behind a skirting-board. The Sunday Times made much of the event: ‘The excitement produced in high life by the dreadful event is almost unprecedented, and the feeling of apprehension for personal safety increases every hour, particularly among those of the nobility . . .’ So prominent and fascinating was the case that even an attempt on the life of Queen Victoria by a young man called Oxford did not make interest recede. When the case came to court at the Old Bailey, there were three earls, a duke and some higher clergy present. It seemed as though the Swiss butler might not be charged, as everything was circumstantial, but then there was high drama when a woman brought some engraved silver spoons which had been left by Courvoisier at her home not long after the murder. This meant that he would hang.

The butler confessed on the scaffold. There were probably around 40,000 people there to see Calcraft hang Courvoisier on 6 July. Among the crowd were the two great writers Thackeray and Dickens. Dickens was very deeply affected by what he saw, and a few years later he wrote in the Daily News about the horrible spectacle: ‘It was so loathsome, pitiful and vile a sight, that the law appeared to be as bad as he, or worse; being much the stronger, and shedding around it a far more dismal contagion.’

The actual hanging was described by The Times reporter, referring to Calcraft and to the victim: ‘During this operation he lifted up his head and raised his hands to his breast. In a moment the hangman drew the fatal bolt, the drop fell and in this attitude the murderer perished without any violent struggle.’

In April, 1849 he had to hang a young woman, Sarah Thomas. Just seventeen and working in Bristol, Sarah was working in service with a hard, cruel woman who used to beat her and deprive her of food. Sarah could take no more and determined to kill her mistress while she slept: she hit her on the head and smashed her skull. She would have to hang, and Calcraft made his way to Bristol to do the job. It was to be a terrible ordeal for him. When he approached her in the condemned cell she cried ‘I won’t be hanged . . . take me home!’ He had to pinion her as she struggled and warders had to help him to restrain her. There was the usual crowd gathered in the yard and the young girl shouted and fought all the way to the noose. He determined to end her life as quickly as possible and did so with real aplomb. Later he said of that case, ‘I never felt so much compunction as I did yesterday at Bristol, having to bring that young girl to the scaffold . . . She was, in my opinion, one of the prettiest and most intellectual girls I have met with . . .’

On 28 November that year, James Bloomfield Rush murdered Isaac Jermy and his son Jermy, at Stanfield Hall near Norwich. Rush also attacked and wounded two women. The murders were over his claim to inherit the family estate. The killer waited until the family were having dinner before he made his move, and the story reads like a modern ‘spree killing’ episode, as Rush appeared wearing a black cloak and wore a mask. He shot the father and son, and also shot Mrs Jermy as she tried to protect her husband. The maid was shot in her thigh. The police soon investigated Rush, as he was the main suspect with a clear motive. He was arrested and stood trial in Norwich. The trial was soon in print, a full account, in small print and with a drawing of Rush prominent. The booksellers got rich, and again, London society took a profound interest in the case.

Norwich castle, where Rush was held and hanged. Pamela Brooks Collection

When it came to the hanging, the regional railway put on special trains for the crowds. The appeal of the drama is not difficult to appreciate: after all, once again, in a home of landed gentry, a slaughter had taken place from within the family - and Mrs Jermy had had to have her arm amputated, following her heroic act in trying to save her husband. Calcraft, as the instrument of the law, both legal and moral, was the public face of proper retribution.

A broadside printed at the time gives minute detail regarding the culprit’s last hours: ‘The condemned convict Rush was visited on Monday by the whole of his family of nine children . . . Parent and children embraced each other . . . a large number of persons waited outside the castle to witness the departure of the prisoner’s family . . .’ The rituals of executions were changing from the sheer directness of ‘the last dying words’ speeches and Newgate biographies to the vicarious pleasures of learning, with morbid fascination, about the felon’s last hours, intimately and with a certain degree of sick interest.

The scaffold was outside Norwich gaol. So cool was Rush that, even when hooded and ready for death, he said to the hangman through the material, as the noose was tied,

‘Put the noose a little higher, and take your time!’ There was a massive crowd watching, and of course Rush had been loudly abused as he walked to the scaffold. Calcraft did the hanging quickly, but of course, Rush took some minutes to die. As usual, death was by strangling.

As is usually evident in any biography of a hangman, there were mistakes, fiascos and failures in Calcraft’s career. In 1856, for instance, at Newgate, he had to hang the killer William Bousfield. The condemned man had been desperate to take his own life and to cheat the noose; he had even put his face into the fire in the cell. The man was then carried out to meet his death, but matters were exacerbated by the fact that Calcraft had been sent a threatening letter, saying that he would be killed if he hanged Bousfield. There was the man waiting to hang, sitting in a chair, and the hangman expecting to be shot at any second; Calcraft quickly pulled the lever to release the drop and then ran inside the prison, expecting a bullet. But the victim had grappled with the edge of the platform and had not yet swung when Calcraft was induced to return to the scaffold. Eventually, the man was pushed to his death. His legs had to be held.

We have a few scraps of anecdotes about Calcraft other than the accounts of hangings. Sergeant Ballantyne, for instance, wrote his memoirs in 1882 and wrote: ‘It is only right, whilst mentioning the celebrities connected with the Old Bailey, that I should allude to one other personage. Rarely met with upon festive occasions, he was, nevertheless, accustomed to present himself after dinner on the last day of sessions. He was decently dressed, a quiet looking man. Upon his appearance he was presented with a glass of wine. This he drank to the health of his patrons, and expressed with becoming modesty his gratitude for past favours and his hopes for favours to come. He was Mr Calcraft, the hangman.’

Calcraft retired in 1874, just as the genius of the science of hanging, William Marwood, was coming onto the scene. As the doyen of hangman history, Geoffrey Abbotts wrote of Calcraft’s demise: ‘It is likely that, having lost his wife and now his job, he simply lost heart, for he subsequently became more of a recluse, dying in his home in Poole Street on the evening of Saturday 13 December 1879.’