efore William Marwood from Horncastle, Lincolnshire, emerged in the 1870s as a hangman who was to exhibit a whole new attitude to the profession, there was a considerable movement for reform and abolition of the death penalty. The Consolidation Act of 1861 abolished capital punishment for all offences except treason, murder, piracy with violence and arson in dockyards. In the mid-Victorian years there were fewer hangings, and notably in 1854 there were only five hangings; there was a groundswell of opinion that hanging should be abolished. In 1864 there was a debate in the House of Commons and a Royal Commission was established to look into the matter. There had been a previous enquiry held in 1856, specifically looking at public executions, reporting on ‘the present mode of carrying into effect capital punishments, chaired by the Bishop of Oxford.

efore William Marwood from Horncastle, Lincolnshire, emerged in the 1870s as a hangman who was to exhibit a whole new attitude to the profession, there was a considerable movement for reform and abolition of the death penalty. The Consolidation Act of 1861 abolished capital punishment for all offences except treason, murder, piracy with violence and arson in dockyards. In the mid-Victorian years there were fewer hangings, and notably in 1854 there were only five hangings; there was a groundswell of opinion that hanging should be abolished. In 1864 there was a debate in the House of Commons and a Royal Commission was established to look into the matter. There had been a previous enquiry held in 1856, specifically looking at public executions, reporting on ‘the present mode of carrying into effect capital punishments, chaired by the Bishop of Oxford.

William Marwood. Laura Carter

The sixth Duke of Richmond was the chairman, a Tory, and he had such men as Gathorne Hardy and Lord Stanley on the Commission with him. Their recommendations were that there should be two divisions of murder, ‘degrees’ - and that first degree murder should have the death penalty. They also thought that the tricky subject of infanticide should be understood separately from murder, that judges should be given the power of the sentence again, and that public executions should be ended. Some members of the group, including the famous speaker John Bright, wanted the death penalty abolished. A long debate on the ‘two degrees’ followed and in the end, it was decided that a better distinction was the murder/manslaughter one. The definition of murder was that the aggressor clearly had an intention to take the life of another, or to do grievous bodily harm ‘dangerous to life’. Spencer Walpole in the Conservative government, tried to institute five varieties of homicide, all versions of murder, but that failed to materialise. Homicide Amendment Bills in 1872 and 1874 were attempted and even by 1878 the bill failed to bring about radical reform. But at least public executions stopped, in 1868.

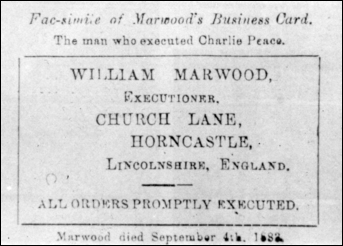

Marwood’s business card.

Author’s collection

Cobb Hall, Lincoln Castle, the hanging place. The author

William Marwood stepped in as principal hangman at this time, taking up his first work in 1872, and hanging 167 criminals between that year and 1883. Marwood was to become legendary in popular culture and a quip about him was circulated: ‘If Pa killed Ma, who would kill Pa? Marwood.’ He was a shoemaker by trade, and in his shop he used a trapdoor in his warehouse hoist on Wharf Road, Horncastle, to perfect what would be his long drop method, a more humane way of helping a felon into the next world. Marwood realised that the normal method of hanging was brutal, in that the rope was tied haphazardly at the neck, and so death was by slow strangulation. He saw that a longer drop, in relation to the weight of the victim, together with a knot tied at the main artery, would make for a speedy end.

In 1879 he was interviewed by a writer from the Lincoln Gazette; he was described as having a hard face, ‘shrewd’ but not unkindly’. The interviewer provided a fuller account:

(his face) was strongly marked, rugged almost in its deep lines and furrows. The eyes were quiet, resolute and penetrating; the mouth shut firm and tight as one of his own nooses . . . What struck me most were his hands – knotted, twisted, vigorous hands, the hands of a man who had worked with them for years at some severe manual labour and who could use them with Herculean strength and tenacity if required.

Marwood told the journalist that hanging was ‘All as stops murder.’ He argued that fear of the rope ‘kept a man’s blood down and his temper cool’ and he said that hanging killers was ‘Only another way of controlling vermin - vermin have a mortal sting and as such should be put out of the way of doing harm . . .’

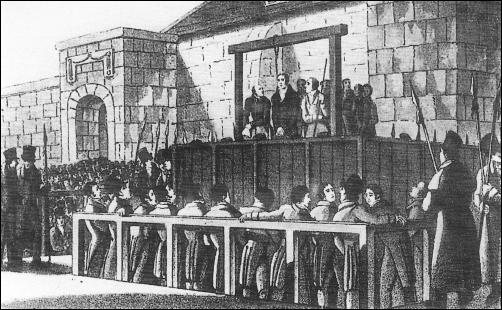

Gallows at York shown in Calcraft’s time. Author’s collection

He was not at all bothered by the reputation his trade had for the public. In fact, he agreed to sit for his effigy at Madame Tussaud’s establishment and John Theodore Tussaud remembered him well, recalling that Marwood used to go to the studios when he was feeling melancholy, drink some gin and smoke a pipe. Then he would walk around the chambers, enjoying the thrill of seeing the waxworks of some of the people he had executed. Tussaud wrote, ‘He had no objection to his own effigy being in their company . . . Usually he was accompanied by his old dog, a grizzled terrier that had played with his ropes and caught rats in his master’s business bags. On one occasion he was at the chambers, feeling down, and talked about his dog dying. Someone listening thought it was fun to ask Marwood if he should not hang the dying creature, and the hangman replied, ‘No, hang a man, but my dear old dog, never!’

Marwood took his business very seriously and he was much in demand. A letter to his wife Ellen gives a clear impression of his lifestyle, printed here with his spelling:

Dear Ellen,

This is to say that I sent a letter on thousday last on my arrival at Clonmal in Ireland t say that I was all well – now this is to say that I left dublin last night about 9 a clock for Hollehead arrived about 3 a clock this

For Birmingham arrived about 11 a clock to Day I ham now in Birmingham With the governor waiting to see the governor of Bristol at half past towTo Day and then I leave here for Cambridge. This afternoon all well so ifAll well I shall return on Monday night or Tuesday morning I hope all is wellAt home tell my poor boy nero that is marster is coming home, remember meTo Mrs Moodey I hope she will call on Sunday to take tea now take good . . . ofMy poor nero be good to polley I hope I shall find all things bright on my Return . . .

His spelling was clearly not as good as Calcraft’s, who was always a capable scholar. But this does indicate the sheer intensity and rush of his professional life, being that of a travelling expert, reliable and proficient. We also have an idea of his payment, as this letter from the sheriff of Galway notes in 1882: ‘There are a number of executions here on Friday the 15th December next, and I wish to be informed if you will be able to carry them out on the day named, and also your charge for same. As it is always one day’s job, I presume your charge will be the same as last time, £20 for the day.’ The sheriff, Mr Midlington, made it clear that the costs incurred came out of his own pocket, perhaps hinting that he did not expect a rise in the charge.

Marwood was destined to officiate at some notable and often infamously political hangings. His trip to Galway in response to the above request was one of the most sensational trials and executions in nineteenth-century Ireland. Known as the Maamtrasna murders, the brutal events meant that three men were to be hanged: Patrick and Myles Joyce and Patrick Casey. What happened was that Marwood found himself being accused of making a mess of things. The Western Mail explained the furore:

After hanging an hour the bodies were taken down, and Mr Collingham held an inquest. After formal evidence had been given, Dr Rice was examined and deposed: “I am surgeon at Galway gaol, and have examined the bodies of the three men executed this morning. Patrick Casey died of a fracture of the cervical spine, and death in this case must have been nearly instant . . . Patrick Joyce had exactly the same injuries . . . Myles Joyce died from strangulation, no fracture of the neck bones having taken place at all. I consider that death took place over one to two minutes . . .

The Galway officials were displeased, and the jurors said that they wanted Marwood there to give an explanation. It was said that Marwood was at fault because, as Myles Joyce was ‘not so passive as the other two’ the hangman should have tied his knot first.

This was a familiar incident in nineteenth-century hanging. Even the best hangman made mistakes, and it was at multiple hangings that they were most likely to happen. In this case (and it was a rare thing) Marwood’s response was printed. The hangman said, ‘Myles Joyce had in some way got his hand entangled in the rope and he had been trying to push it down. Death was instantaneous, as there was nothing wrong with the rope, I have used it before at Limerick, York Castle, Bodmin, Cornwall and Worcester . . . I gave all the men an equal drop of nine feet . . .’

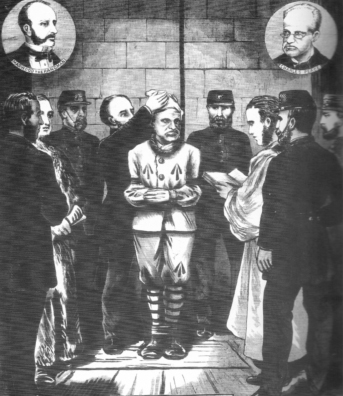

His most celebrated hanging was surely the execution of the famous Phoenix Park murderers in 1882. A gang had murdered the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Lord Frederick Cavendish, and his under-secretary, in broad daylight in Phoenix Park, Dublin, while the victims were walking in the park. Four men had leapt from a cab and stabbed him to death. The ‘Irish Invincibles’ as they called themselves, sent black-bordered cards to the Dublin papers. Joseph Brady had gone with one group and Daniel Curley with another, after a planning meeting at Wrenn’s Tavern near Dublin Castle. They agreed to split up and decide on where the attack should take place. They had made sure that they had correctly identified Harry Burke, the under secretary, so there would be no mistakes. As they were gathering in the park, there was almost a very big problem for them because a police superintendent called Mallon was going to the park to meet one of his contacts and he met a plain-clothes detective who warned him of at attempt on his life; Mallon left, so the coast was clear for the assassins.

Another turn of fate for the victims was that Cavendish had been offered a ride instead, but had insisted that he walk with Burke. As Cavendish was only just in place as the Secretary there were things to talk through, and a stroll seemed a pleasant way to do that. But they were walking to an appointment with death. After a man called Timothy Kelly had advanced and knifed Cavendish, the gang were soon upon them, with Brady cutting Burke’s throat in the assault. They made their escape, hoping to drive around the city and approach Dublin from another entrance, thus making a platform for some kind of alibi, but a detective had seen a number of them and would later identify them. The first move in apprehending the gang came when a driver broke down and told the tale. It was not long before they were tried and sentenced and William Marwood was crossing the Irish Sea with his ropes and pinion.

Sixteen of the Invincibles were tried and five were hanged; James Carey turned state’s evidence. Joseph Brady was executed on 14 May, sentenced to death by Mr Justice O’Brien, and others followed, Marwood hanging them at Kilmainham gaol. The events went down in popular history, as in the song Monto recorded by The Dubliners, in which we have the rhyme:

When Carey told on Skin-the-goat

O’Donnell caught him on the boat

He wished he’d never been afloat the filthy skite,

‘Twasn’t very sensible

To tell on the Invincibles

They stood up for their principles, day and night..

Marwood’s other outstanding cases were the execution of master criminal Charles Peace and of Kate Webster, the latter being one of the hangman’s more efficient jobs. Kate was born in Ireland but settled in London. In 1879 she worked in Richmond, as housemaid to a Mrs Julia Thomas. Kate liked a late-night drink and loud company, and her employer was very strict, tending to reprimand her too often and a level of antagonism developed which escalated into something very savage. Kate Webster, in a torrid temper, went for an axe and then sliced into Mrs Thomas’s head with the blade.

Kate Webster then cut up her employer’s corpse. She tried to boil away the remains, and she had a tough time scrubbing the walls clean of blood because hacking with an axe is very messy. Her plan was to take bits of the body out in bags, a few pieces at a time, and throw them into the Thames. Then, as she realised that she could steal the identity of the lady, she did so and tried to sell the house. Dumping bodies is often the flaw in a killer’s designs and so it was with Kate. A fisherman found some of the sacks and reported that to the police. They were soon on Webster’s trail.

She was back home in Killane, Ireland, when the officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary arrived to arrest her. Then she was found to have some of the stolen valuables at her home; Webster was brought back to stand trial at the Old Bailey, and was sentenced to death. There was a story in circulation that she had made human dripping from some of the body parts after slicing them, but that was surely an urban myth. The only mystery at the end of the case was the whereabouts of Mrs Thomas’s head. She protested her innocence and even on the day of her execution, she caused problems for Marwood, shouting and insulting him and the whole legal process. But this time Marwood was on top form, doing his calculations accurately and ensuring a swift end to her life.

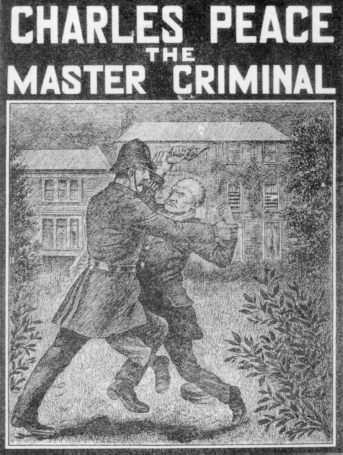

Charles Peace, the Master Criminal, cover for an old local chapbook. The author

The Victorian public believed, on the whole, with Shakespeare’s line, ‘Where the offence is great, let the greatest axe fall.’ When it came to the case of Charles Peace, there was very little clamour to spare his life. He had become the most notorious villain in Britain up to the advent of Jack the Ripper. Every aspect of his story suggests legend, folk tale, and an element of the grotesque. But he was undoubtedly a candidate for the Holmesian title, ‘Master Criminal’ as everything about his life was unusual. He was born in 1832, the son of a one-legged lion-tamer, John Peace, and by the age of twelve he was working in a rolling mill at Sheffield, called Millsands. It was a fearful accident at this mill, when a red-hot bar impaled him in the leg, that led to the first stage of his fearsome and ill-formed appearance in later life.

But Peace earned a living, after coming through this, playing the violin and starting a career of petty crime. Ayer writing in 1906 noted, ‘He learned to play the violin and learned so quickly that after his recovery he was in demand at concerts . . . On one occasion he had an engagement at a theatre and was billed as ‘The Modern Paganini.’ His performance consisted of playing on a single string. Unfortunately, his name is linked more with his most notorious murder, at Banner Cross in Sheffield. In 1876 he was in Manchester and he killed a policeman there. Another man, William Habron, was tried and convicted for this, and Peace attended the trial, later saying he had enjoyed the spectacle.

But he began to harass and trail a Mrs Katherine Dyson, the wife of an engineer Peace had got to know. He became such a threatening nuisance that the Dysons moved house, but Peace followed them, and one night as Katherine went to an outside toilet, Peace was there, and he had a gun. When Mr Dyson came out, he was shot. Peace said, ‘I’m here to annoy you, and I’ll annoy you wherever you go.’ He shot Dyson in the head.

Peace then moved to London and began a new life, living as a Mr John Ward. He put up a front of living as an amateur businessman and inventor, but at night he was still doing robberies and burglaries. As he always had a gun on him when at work, he shot and wounded a police officer one night while being chased after a robbery. It was when his mistress, Susan Ward, informed on him that the law finally caught up with the man who did the Banner Cross murder.

Then, in grand comic-strip tradition, Peace tried his most daring escape. He was being escorted to Leeds to stand trial for the Yorkshire murder, and he asked permission, while on the train, to urinate. The escape meant he had to throw himself out of an open carriage window while his handcuffs were momentarily taken off. He dived out but the attempt failed; he was stuck fast and attempted to kick free and hung from the window before falling and seriously injuring himself. He was recaptured and then sent to answer the murder charge in the dock at Leeds. Peace was proved to be the man who killed Arthur Dyson and was sentenced to hang. He may have been responsible for more murders than those at Banner Cross and at Whalley Edge, Manchester.

Armley gaol, where Peace was hanged. Laura Carter

Marwood hanged Peace on 25 February 1879. The papers were still full of the stunning achievement of the soldiers at Rorke’s Drift during the Zulu War., but Peace’s death made the headlines and the front page of the Police News which showed Marwood performing the execution and featured a drawing of Marwood’s face which is one of the clearest images we have apart from the Tussaud effigy. To the very end., Peace was a ‘character’. He joked, ‘I wonder if the hangman can cure my sore throat!’ Being a man with a sense of drama., he insisted on a last speech., for the sake of the reporters. He said, ‘Say my last wishes and my last respects are to my children and their dear mother. I hope that no person will disgrace himself by taunting or jeering them . . . Oh My Lord have mercy on me!’

As for Marwood., cool as always., he said simply, ‘He was such a desperate man., but bless you dear Sir., he passed away like a summer’s eve.’ But Peace will always be remembered as one of Yorkshire’s most successful thieves and rogues. Teignmouth Shore once described him: ‘Slight as was his frame., his strength was enormous’ and there were tales about his habits and rackets., such as this., described by Shore in the same memoir:

Further light upon this really amazing fellow is provided by Sir William Clegg; I quote from one of his letters . . . ” a small, spare man, clean shaven and with a very prominent chin, which he could so distort as to make himself almost unrecognisable. Whilst he was in custody . . . he informed me that on many occasions he went to Scotland Yard for the purpose of reading the notice offering the reward for his own apprehen-sion, but that by manipulating his jaw he could escape detection . . .

Marwood’s public profile was raised considerably by his connection with such notable cases, of course, and hanging itself was in the news. One bizarre footnote to this was the advent of ‘amateur hanging’. In The Times under that heading was this intriguing note: ‘It has often been remarked that in this country a public execution is generally followed closely by instances of death by hanging, either suicidal or accidental, in consequence of the powerful effect which the execution of a noted criminal produces upon a morbid and unmatured mind.’ After an execution in 1850, a Sheffield lunatic hanged himself, and the Morning Advertiser of 1849 noted that after the execution of Sarah Thomas in that year there was an amateur hanging death of a man called Yardley, a parricide, by hanging and a family massacre in which a man killed his children, and with the use of a rope. The whole topic was similar to the recent debates on the negative influences of video nasties; one thing is certain - the high profile media attention given to killers such as Peace and Webster did produce images of the hanging ritual in the public mind.

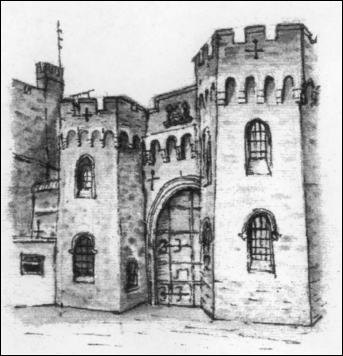

The Castle Hill Club, Lincoln. Marwood stayed in the attic. The author

William Marwood’s life was eventful and sometimes mysterious, too. After the Phoenix Park hangings he was sent a threatening letter saying he would be assassinated. But his life went on, doing his unpleasant work from town to town. In his own home city of Lincoln he was in the habit of staying in an attic room of what is now the club to the left of the entrance to Lincoln Castle. He was fond of a pint and a pipe and quietly went on with his business.

Marwood’s cases in Lincoln were less sensational, and if we look at the hanging of Peter Blanchard on 9 August 1875 for instance, we have a glimpse of the more everyday jobs for the hangman with the long drop. Blanchard was a tanner from Louth, just twenty-six when he became jealous of Louisa Hodgson, his fiancée. She was friendly with a farmer called Campion and Blanchard didn’t like it. He took a knife and waited until Campion came out of chapel, but instead of going for him, he later turned his ire on Lousia, stabbing her in her own kitchen. When told that the woman was dead, Blanchard simply said, ‘I’m damned glad!’ Marwood hanged Blanchard at the Castle, on Cobb Hall, on a rainy day when a large crowd had gathered. There was a thunderstorm as he body fell and the legs jerked. The black flag was raised over Lincoln that day, and the townsfolk knew that William Marwood had been coldly efficient yet again, in ridding the place of its ‘vermin’.

Marwood tended to invest his money, but lost most of it unwisely. At his death he was penniless, dying after a fall at a pub while in his cups; and some said that he had been poisoned by the Fenians in revenge for the Invincible hangings. It was 4 September 1883. He was buried in an unmarked grave in the churchyard at Horncastle.