ames Berry was a man who came to his vocation as hangman after a long list of failures and dead ends in his search for a career which would satisfy him. After a rough and eventful childhood in which he narrowly escaped death or serious injury on a number of occasions, he began to take note of the work being done by Marwood in his fairly short but import reign as public executioner. Marwood, as already briefly mentioned, laboured hard to refine the art of hanging, with attention paid in more detail to the weight of the body and the length of the drop down the trapdoor. The process generally demanded a swiftly handled sequence of actions following the movements of putting on the cap, placing the noose, removing the pin in the lever-frame, pulling the lever and finally making sure the trap and drop worked.

ames Berry was a man who came to his vocation as hangman after a long list of failures and dead ends in his search for a career which would satisfy him. After a rough and eventful childhood in which he narrowly escaped death or serious injury on a number of occasions, he began to take note of the work being done by Marwood in his fairly short but import reign as public executioner. Marwood, as already briefly mentioned, laboured hard to refine the art of hanging, with attention paid in more detail to the weight of the body and the length of the drop down the trapdoor. The process generally demanded a swiftly handled sequence of actions following the movements of putting on the cap, placing the noose, removing the pin in the lever-frame, pulling the lever and finally making sure the trap and drop worked.

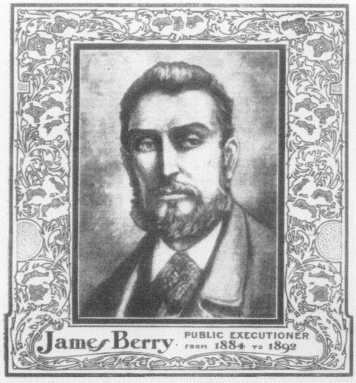

James Berry. Author’s collection

Berry, as he noted in his letter of application after Marwood’s death, made a point of stressing that he had actually met and taken advice from the Lincolnshire shoemaker. Marwood had become infamous: the rhyme, ‘If pa killed ma, who would kill pa? Marwood.’ This was in common currency and he had been immortalised at Madame Tussaud’s waxworks. Berry had paid attention to the skills involved in the work, and it seems that although money was not the major consideration, it was very important to him at the time because he had a wife and family to house and feed. Berry had served in the Bradford police and so had some knowledge of the criminal world and of the nature of urban crime, violent or otherwise. But he soon realised how different and of course, how unique the craft of executing felons actually was in practice.

It was Binns’ failure that opened up the work to him; he had been pipped at the post when Binns was first employed, being second in a very long list of applicants. In fact, one of Berry’s abiding faults was a bold egoism and lust for publicity as well as respect, and that very nearly cost him the career he sought. He told the press that he had the post before it was really secured. But it appears that the selection panel were so impressed with his profile and past initiative, as well as in his long-standing interest in the work, that they appointed him gladly.

Of course, any of the figures in authority would have soon been aware, had they looked back on the previous hangmen in the century, that there was a likelihood of embarrassment and shame attached to the post, largely as a result of the tendency for the incumbents of the profession to take to drink and to suffer from what we would now call work-related stress. But something about Berry’s manner and air of confidence brought him into favour.

James Berry was born in February 1852, at Heckmondwike, where his father, Daniel, was a wool-stapler. He had a hard time at school and his nature contained a strong streak of rebellion which led him to try to run away to sea, play truant and get into all kinds of scrapes. But his police service apparently caused a significant change in him, primarily in his self-regard and confidence. He wrote in his memoirs with an arrogance and vanity about his successes there (and later in the Nottingham police for a short while) with outstanding claims. His achievements read like a Sherlock Holmes of Yorkshire. But both in Bradford and in Nottingham he was restless and demanding, and his personality was abrasive and combative, leading ultimately to resignation.

He had been considering the appeal of the welcome income of the hangman’s trade for some time; his range of employment had brought continual frustration and some real financial hardship. But certainly in the case of execution work, he had taken it seriously for some time. When his memoirs were first published, serialised in the Saturday Post magazine in 1914, he explained the source of his aims to work as hangman in this way, after he heard newsboys shouting out the news that Marwood had died:

Berry’s table of drops. Author’s collection

It almost seemed as if fate had kept me poor to drive me into the position. It seemed that I was predestined from birth to become the follower of Marwood, for, extraordinary though it may seem, the Chief Constable of Bradford was setting out to ask me to take the job at the very moment I was setting out to ask him to use his influence with the people of London.

We have to speculate what character traits in Berry had impressed themselves on the Chief Constable, James Withers. It is very difficult to ascertain exactly what qualities would lead someone to see the potential of ‘public hangman’ in a person. A profile, taking in the men who have filled that role in British history, would have to include features including religious calling, odd altruistic need to participate in Mosaic justice, and of course, the appeal of cash or freedom in the tradition of felons turned executioners, particularly in Yorkshire. In Berry’s case, financial reward was part of it, but the superiors in the police force and perhaps also Marwood (they did meet) saw something else.

Arguably the best way to locate this elusive quality is to observe how he acquired his professionalism and that is closely recorded in the events around his very first job, in Edinburgh in March 1884. We would expect a man to recall such an experience in great detail, and such was the case. The victims in question were two poachers, William Innes and Robert Vickers. There was still a common feeling around that poaching was a social crime, and that gamekeepers were very much reproached for their work. Some thought that the two men would have a reprieve. But it was not to be, and the account of Berry’s weekend there, as retold by Stewart Evans in his recent biography of Berry, makes it clear that the Bradford man was extremely impressive, and as one would expect, he had to go through the hellish torment of that first ordeal, knowing he was taking two young lives, judicially sanctioned or not, still a kind of homicide.

From the Life of James Murphy.

Author’s collection

Berry, with his mysterious assistant with a pseudonym of ‘Richard Chester’, gives an account of the whole period, from arrival on the Thursday to departure after the job was done. He certainly did his homework, doing all kinds of tests on the gallows such as using bags of cement as the body-weights and of course, calculating the drop required. His religious faith played a part, as he asked for guidance from the Almighty, but also the professionalism in him came through, seen clearly in the way his mental strength held strong against all the emotional and sympathetic thoughts that assailed him as he had to spend many long hours inside the grounds, thinking of the enormity of what he was about to do.

As Stewart Evans describes, the hanging itself was notably efficient and it pleased the officials from the prison and other medical men - a rare achievement in this trade. Berry wrote, ‘Everything was done as quick as lightning, and both culprits paid the highest penalty of the law . . .’ As Evans also points out (and this is a real mystery), Berry departed from Marwood’s practice in one very significant way, and that was in respect of where the knot was placed on the neck. Marwood’s belief, later supported by a group of surgeons, was that the knot should be fastened submentally, that is, under the chin and on the left. Berry made his knot under the left ear. That would almost certainly not be as rapid and efficient as a knot over the major artery under the left front of the chin; it would make more of a forceful jolt, affecting the spinal column differently also.

Berry only did one hanging in Yorkshire, but it was a sensational case: that of the Barnsley murderer (again, a poacher) James Murphy. He was a Dodsworth collier who had experienced the urgings of a personal vendetta against a constable called Austwick. Ever since Austwick had arrested him for drunkenness, Murphy had had a burning hatred against the officer. He later went out, with a clear intention of killing Austwick and did so, then after a few days on the run he was tracked down and arrested.

Surely the most remarkable aspect of the Murphy case was his nonchalance and fortitude in the face of the scaffold. Berry has left a detailed account of the conversation he had with the killer, on entering the cell as Murphy was chewing a mutton chop, fully aware that his death was only a few hours away. At the end of the talk, Murphy made a joke. Berry asked, ‘I hope you won’t give me any trouble when the time comes,’ and this followed:

He looked at me and smiled.

‘I won’t give you any trouble. I am not afraid to die. A lot of people have been making a fuss over this business, and I’m hanged if I can see what there is to make a fuss about.’

I was so surprised at his joke, that I could say nothing, and so I left him and did not see him again until I went to pinion him.

Lincoln Assizes. The author

In Berry’s career as hangman, he had the especially painful duty of executing five women. One of these, the case of Mary Lefley in Lincolnshire, provides one of the most heart-rending and contentious hangings in the entire record of British capital punishment.

In the Lincolnshire village of Wrangle, Mary Lefley, aged forty-nine, lived with her cottager husband, William, ten years her senior. They were living in a freehold property and seemed reasonably happy as far as anyone was aware. On 6 February 1884 various friends called at their cottage and everything seemed normal. Mary set off for Boston to sell produce, and later in the day, around three in the after-noon, William arrived at the home of the local medical man, Dr Bubb. Lefley was extremely ill and the doctor was not there. He staggered in and hit the floor, retching and moaning. He had brought a bowl of rice pudding and told some women present that it had poisoned food in it.

When he was told again that Dr Bubb was not at home, he said, ‘That won’t do. I want to see him in one minute, I’m dying fast.’ A Dr Faskally (the locum) then came and examined him; it was a desperate situation, yet for some reason the doctor had Lefley carried to his own house, where he died.

When Mary came home that evening her behaviour was confused and to some, irrational, which was to have repercussions later on. She actually stated to the doctor that she expected Lefley to claim that he had been poisoned. What was then reported about her is strange indeed. A neighbour who was trying to help made her some tea and Mary said, ‘I’ve had nothing all day because I felt so queer.’ Then she talked about making the pudding. ‘He told me not to make any pudding as there was plenty cooked, but I said I always make pudding and would do so as usual.’ In themselves, these two statements are quite innocuous, but in the context of the later trial they were to prove lethal to her.

At Lincoln Assizes in May 1884 she was in the box; there was no other suspect. The police were convinced that there had been foul play and she was the only suspect. She had been charged on circumstantial evidence only and she pleaded not guilty. But then she had to listen to an astounding piece of evidence from the post-mortem. There had been a massive amount of arsenic in the rice pudding: 135 grains. A fatal dose needs only to be two grains. Despite the fact that some white powder found in her home was found to be harmless, witnesses were called and the trial proceeded. The strongest testimony came from William’s nephew, William Lister, who recounted an argument between the couple when his uncle had taken a great quantity of ale. William came to his nephew’s bed and told him that he had just attempted suicide.

A typical Victorian depiction of a female killer – Mrs Manning. Author’s collection

Other witnesses said that they had heard Mary say that she wished her husband was ‘dead and out of the way’. It was a tough challenge for the defence, and they failed. Mary was sentenced to death and her reply was, ‘I’m not guilty and I never poisoned anyone in my life.’

There is a great deal of detail on Berry’s account of the horrendous experience of carrying out her execution. Berry, new to the job and anxious to do things right, was of the opinion that he was going to hang an innocent woman. But he was a professional with a task ahead of him and he carried on. He wrote his own account of the process in his memoirs:

To the very last she protested her innocence, though the night before she was very restless and constantly exclaimed, “Lord, thou knowest all!”

She would have no breakfast and when I approached her she was in a nervous agitated state, praying to God for salvation . . . but as an innocent woman . . . she had to be led to the scaffold by two female warders.

Berry records that Mary was ill when he went to fetch her on that fateful morning. She also shouted ‘Murder!’ Berry wrote with feeling and some repugnance about the whole business, and at having to pinion her. Her cries were piercing as she was dragged along to the scaffold. As Berry reported, ‘Our eyes were downcast, our senses numbed, and down the cheeks of some the tears were rolling.’ After all, as soon as Berry had arrived at the gaol, a woman warder had said to him, ‘Oh Mr Berry, I am sure as can be that she never committed the dreadful crime. You have only to talk to the woman to know that . . .’ Berry noted that he ‘found the gaol in a state of panic’ when he arrived. He recalled that the chaplain’s prayers had sounded ‘more like a sob’ on the last morning of Mary Lefley’s life.

The final irony is that, if we believe Berry, that a farmer, who had been humiliated in a deal with Lefley, confessed to the poisoning on his deathbed. He said he had crept into the cottage on that day and put the poison in the pudding.

Berry had always been the kind of man who, when he eventually found his vocation, would revel in it, enjoy it to the full in terms of both inner satisfaction and in his need for acclamation and self-advertisement. Earlier in his life he had made the most of the smallest achievements, showing his ability as a ‘spin-doctor’ of his own status and reputation. He even had a business card produced, with delicate leaves across the card, his name beneath and his address of ‘1, Bilton Place, Bradford’ also. The card proclaims his profession as well as his name and address: ‘James Berry: Executioner’ as if it were as ordinary a trade as a blacksmith or a printer at the time. But his life after his hangman years reveal a very different inner personality, more complex than one would have inferred from his public life and opinions.

Berry managed to indulge in all kinds of hobbies and part-time jobs when his career ended. He had various items as souvenirs and some of these were sold to Madame Tussaud’s. He also began to take part in lecture tours, as there was always a morbid interest in the general public in the subject of execution. He moved to different addresses in the Bradford area, and he still had his wife, mother-in-law and one of his sons living with him at the time of the 1901 census. It is at this time that we begin to discern some of those deeper qualities explained at length in a vignette of him by his editor, Snowden Ward, who wrote that ‘His character is a curious study - a mixture of very strong and very weak traits such as is seldom found in one person.’ Ward also noted something that also applied to Albert Pierrepoint later: that his wife knew little of her husband’s professional activities. She said that she had lived with him for nineteen years but that she still did not really know him.

Berry had always been a man who looked to any kind of legal activity for earning a few pounds, and that habit was still with him when he was described as ‘commission agent, late public executioner.’ But his media career was a failure and he took to trading for small profits in retail. What began to emerge then was the drinking habit, something that became more serious as time went on. He once expressed this frankly and simply: ‘I knew that it was drink that was the main support of the gallows.’ What happened then is that he wrote begging letters to prison authorities and to people in high places in the prison establishment, asking for his job back. But things had moved on and the general attitude was that there was no point in employing a man who had ‘given them trouble.’ And there were younger men coming through.

Surely one of the most dramatic and compelling stories of this complex man’s life is the account of his reclamation, spiritually, after walking out of his home one day with the intention of taking his own life. He wrote in his memoirs, ‘I could not have thought it possible that mortal man could become so low and depraved . . . My burning conscience accused me of having wronged my family - my innocent, good and virtuous wife, and my sorely suffering children - with my carryings on in sin and wickedness. There was nothing else for it - I must put an end to my life.’

What happened was that, as he sat on a railway platform, intending to throw himself from the window of a train in a tunnel between Leeds and Bradford, he began to pray for help and guidance, and a man came onto the platform who was in fact an evangelist. He sat with Berry and somehow a shared and very public prayer, with a gathering crowd, led to his being taken in for help by a man who ran a mission hall. In short, Berry found his spiritual redemption on that railway platform; his life was saved and he became a changed man.

He published one more book: a short one called Mr J Berry’s Thoughts Above the Gallows, published in 1905. It was a tract against hanging and a clear assertion of a path to salvation, willed out of his past life, both public and private. There is a quiet desperation running through everything he wrote, but this final work maintains that thread of eccentricity that was always in him, with a discussion of one of his latest fads, phrenology.

He was then an evangelist, but the paraphernalia of his main occupation lingered on through time, a batch of his possessions being exhibited in a Nottingham junk shop in 1948, and in the 1950s, Berry’s granddaughter still had some relics of Berry’s to pass on.

James Berry died at Walnut Tree Farm, Bolton, Bradford, on 21 October 1913. It is entirely in keeping with the man and his character that the local obituary should contain an anecdote about Berry trying to sell the cigar-case of a man he had executed. That note of desperation and the need for small profits, while at the same time feeling a sense of the grandeur of his past, sums up one of the puzzles of Berry the hangman - a rare mix of dignity and low life street hawking. He always looked to a quick profit and somehow, as with almost all hangmen in the records, never fully accommodated his professional self with his self-esteem.

He was a man of profound contradictions, with a reputation which attracted the media. As one journalist wrote after hearing Berry talk, ‘He subsequently went a-lecturing and in that capacity introduced us to quite a modern pronunciation of the word guillotine. He called it gelatine . . .’ They liked to laugh at him, though always with a shiver of revulsion.