fter the hanging of Edith Thompson in 1923, Margery Fry, a social worker, sent a statement to the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment. She wrote: ‘I was at that time living in Dalmeny Avenue close to Holloway prison, and as a visiting magistrate was frequently in the prison . . . I offered to visit Mrs Thompson because I thought she might have some messages she might want me to deliver . . . two or three days later I was in the prison and saw the officers . . . I have never seen a person look so changed in appearance by mental suffering as the Governor appeared to be. Miss Cronin was very greatly troubled by the whole affair . . .’ Fry was forthright on the subject of what hanging does to the professionals involved.

fter the hanging of Edith Thompson in 1923, Margery Fry, a social worker, sent a statement to the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment. She wrote: ‘I was at that time living in Dalmeny Avenue close to Holloway prison, and as a visiting magistrate was frequently in the prison . . . I offered to visit Mrs Thompson because I thought she might have some messages she might want me to deliver . . . two or three days later I was in the prison and saw the officers . . . I have never seen a person look so changed in appearance by mental suffering as the Governor appeared to be. Miss Cronin was very greatly troubled by the whole affair . . .’ Fry was forthright on the subject of what hanging does to the professionals involved.

On the other hand, back in the eighteenth century, a rakish aristocrat called George Selwyn, was a man who loved executions and hangmen to the point of fetishistic idolatry. Selwyn, when rallied by some women for going to see the Jacobite Lord Lovat’s head cut off, retorted sharply, ‘I made full amends, for I went to see it sewn on again.’ It was said that he ‘could have fondled a hangman’. He even went to see executions in female costume, hoping to experience the kind of thrill the women (like Madame Desfarges) had at a hanging. These two examples show the extreme ends of the spectrum when it comes to understanding the peculiar ambivalence to hangings that may be observed throughout social history.

Pomp and circumstance of the law: the assize procession at Bodmin. Author’s collection

In the twentieth century, a look at the Home Office figures shows the gradual decline in the percentage of executions in relation to the capital sentences, and there is a marked difference in the years 1900-29 compared with the following years. In the first twenty-nine years of the century, there was the huge number of 664 capital sentences, of which 413 were executed and most of the rest respited (the figure excludes suicides in custody). Then in the years 1930-48 there were 388 convictions and 193 hangings.

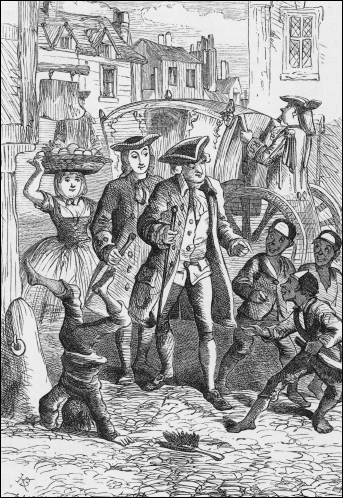

Selwyn, the fetishistic hanging enthusiast. Author’s collection

Into the 1950s we find a much more open and active lobby across all areas of the criminal justice system working for reform. In 1961 two Penguin Special publications confronted the vexed questions of the hanging of innocent people and the controversial topics of police investigations such as forced confessions and the actions following intense pressure to arrest and convict. On top of that, in the 1950s there had also been the issues of hanging women and teenagers, coming to a head with the execution of Ruth Ellis in 1955. Leslie Hale, who wrote one of the two special editions, said of the Ellis case, ‘Blakely . . . wanted to break off the relationship with her in favour of another woman and she shot him one day in the street as he got out of his car, having waited for him, intending to do so. She acknowledged all this. It was pleaded on her behalf that she was hysterical and emotionally immature. She had recently had a miscarriage. No appeal. Hanged at Holloway Prison.’ In that book, Hanged in Error, Hale presented six full case studies of executions in which there was considerable doubt about either the act itself or about police investigation.

Arthur Koestler, who wrote the other book, Hanged by the Neck, printed what he called a ‘Creed for abolitionists’ and in that document he said, ‘The hangman is a disgrace to any civilized country. Doctors have made it clear (through the BMA) that they would never take over the executioner’s job by administering lethal injections. We depend, for our professional killers, on the type of person who voluntarily applies for the job of operating a rope and trapdoor.’

Another instance of the fascination: John Lee, the man they could not hang. He survived three attempts and went free. Chris Wade

Where some of the condemned ended: a flogging yard, felons buried beneath, Port Arthur. The author

The notorious hangmen in Britain have been the men who generally did the work primarily for the second income, or in some cases for cash that made their main income, monopolising on the secondary perks such as selling clothes and receiving payments from the surgeons for dissection corpses. Some have done the work for social and religious reasons, as with Marwood, who spoke of ridding the world of ‘vermin’. Most have suffered terribly for their careers, both mentally and physically. What cannot be denied is the fact that most survived the trauma of their first hanging, and went on to do more, either fortified by drink or possessed by some strange crusading zeal against felons.

The main issues and debates were always about the hanging of women or young people. All but Albert Pierrepoint were involved in such cases. The account I have given of Ethel Major and Edith Thompson highlights these issues. Regarding young people, the turning point came after the 1931 fiasco of a killing by a seventeen-year-old boy of his uncle and aunt in Lincolnshire. The various commissions and enquiries into the hanging of women and children happened over a long time span, and it is disgusting, with the knowledge of hindsight, to look back on that slow progress to enlightenment.

Finally, what about women hangpersons? Apart from a case in America in which a female sheriff almost had to do a hanging herself, there has only been one notorious such figure. This was a woman known as ‘Lady Betty’ who operated in County Roscommon between c.1780 and 1810. She was educated, though she was poor, and the story goes that her dark side expressed itself when she once murdered a stranger who came to her home for shelter. Then, under arrest, her career followed that of man early executioners: she was allowed to live if she hanged others. She reputedly said, ‘Spare me and I’ll hang them all!’ This is a tale somewhere between history and folklore, but it does illustrate the nature of hanging in the popular imagination. Something in the reader of dramatic and sensational history wants to know what judicial murder was really like.

Perhaps what sums up the nature of these notorious hangmen and their morbid attraction is the maxim by Sebastien Chamfort: ‘This morning we condemned three men to death. Two of them definitely deserved it.’ But if we really want a case study in the reasons for notoriety among executioners, we can look to French history for one of the worst ever. This was the executioner Perruchon, called ‘La Lanterne’ because during the French Revolution he hanged anyone who was even a suspicious looking character from the nearest lamp-post. After that he tended to marry the young women who came to plead for their relatives’ lives. He was not worried about bigamy.

Notorious implies a bad or questionable reputation. That can easily be said of any one of the hangmen in the preceding stories. I hope these case studies have opened up a most strange and terrible profession – one we abandoned in 1964 when Peter Allen was executed at Walton gaol and Gwynne Evans, on the same day, was hanged in Manchester.