CHAPTER 10

Army generals fail at Chosin

T he battles around Chosin Reservoir in late November and early December of 1950 would essentially provide a laboratory test for two different American approaches to warfighting and especially to leadership.

The Marines were on the west side of the reservoir, the Army units on the east. Both reported to the same senior leadership and suffered the same winter weather, so cold that rounds for the 3.5-inch rocket launcher froze and cracked open. The Marine division chief of staff at Chosin, Col. Gregon Williams, took a four-minute radio telephone call without a glove on his hand, only to have his fingers turn blue with frostbite later that night. Discussing Chosin years later, Marine corporal Alan Herrington said, “I can still see the icicles of blood.” Indeed, one peculiarity of Chosin was that wounds remained pink and red rather than turning reddish brown, because blood froze before it could coagulate. The cold was a lethal curse but also an unexpected medical ally, because wounds froze shut; it also kept corpses from becoming a sanitation problem.

For both the Army and the Marines, Chosin would be one of the fiercest fights in their history. “I was in the Bulge [in World War II], and it was nothing like this at Chosin Reservoir,” one survivor, Army Sgt. First Class Carrol Price, said later. “I lost all my friends.”

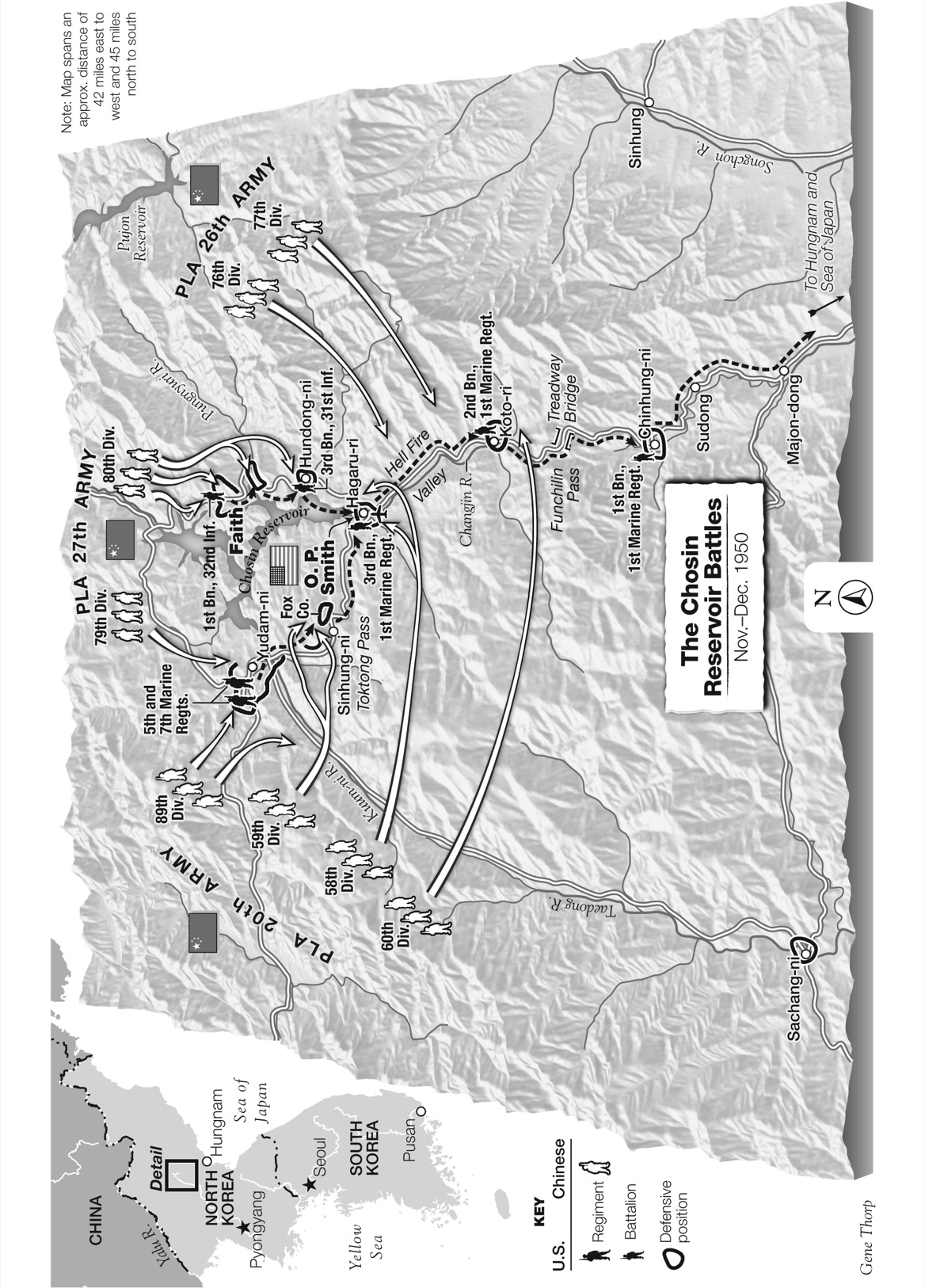

As vastly larger Chinese forces attacked, both the Army and Marine units retreated almost thirteen miles. The Marine retreat would continue in a second phase, another two dozen miles, after it collected the survivors of the Army units. Though both the Army and the Marines faced the same enemy, the Army unit was wiped out, in one of the greatest disasters in American military history, while the Marine division marched out with its vehicles, weapons, and some of the Army’s survivors.

• • •

The battle began about three months after the Inchon landings. MacArthur and his followers were riding high. He and his favorite general, Ned Almond, recklessly pressed their subordinates to attack north toward the Yalu River, the border between Korea and China. They did this despite numerous signs that the Chinese government had inserted thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of troops into northern Korea, not far from the Americans. A collision became inevitable.

When Lt. Col. Don Faith Jr.’s 1st Battalion of the 32nd Infantry Regiment arrived on the eastern shore of the reservoir, it was the first Army element to replace the 5th Marines. That Marine unit was being moved to the west side of the reservoir to join the other Marine regiment there, because Maj. Gen. O. P. Smith, the Marine division commander, being worried by Chinese moves and by his open left flank, wanted to consolidate his forces. Lt. Col. Raymond Murray, the seasoned commanding officer of the 5th Marines, had been studying the terrain on the eastern shore. As he turned over the area to Faith, he recommended that the arriving Army unit dig in and not try to push any farther north. Gen. Smith also passed the word: “Now, look, don’t go out on a limb, take it easy up there.” The assistant commander of the 7th Division, Brig. Gen. “Hammerin’ Hank” Hodes, a veteran of the World War II fighting at Omaha Beach on D-Day, earlier had denied Faith’s request to move north. Nonetheless, with the arrival of Col. Allan MacLean, the regimental commander to which he was attached, Faith pressed again for permission to attack north, up the east side of the reservoir. This time he got approval. In his persistence, he had set the stage for a defeat in which more than three times as many soldiers would be lost as at Lt. Col. George Custer’s Battle of the Little Bighorn.

The Army units on the eastern side of the water were two battalions from the 7th Infantry Division—one from the 31st Infantry Regiment and one from its sister regiment, the 32nd. The 31st was commanded by Col. MacLean, who had spent World War II as a staff officer planning troop movements and who that fall had been given command of the regiment after his predecessor was relieved for a poor performance after the landing at Inchon. The 1st Battalion of the 32nd was commanded by Faith, who not only had never led a unit in sustained combat before but, incredibly, until the Korean War, actually had never been assigned to a frontline combat unit before—not at the squad, platoon, company, or battalion level—having spent all of World War II as an aide to Ridgway. Neither Faith’s battalion nor the 31st Regiment had much combat experience in Korea up to that time. Neither had fought on the defensive, and neither had faced enemy forces larger than a battalion. “The sum total of the 1/32 IN [Infantry] battle experience was the unopposed river crossing at the Han River into Seoul and a few days of combat against the scattered resistance from some of the remnants of the North Korean army in the city,” noted Maj. Paul Berquist in a study done later at the Army’s Command and General Staff College.

Hubris rode north with Col. Faith. The first ominous sign came on the afternoon of November 27, when MacLean sent the 31st Infantry’s Intelligence and Reconnaissance Platoon to establish an outpost on the northeastern side of the reservoir near an inlet. The platoon, mounted on jeeps with machine guns, headed north and vanished, reporting back by neither radio nor runner. It was never heard from again. Faith’s intelligence officer also was picking up word from Korean civilians that Chinese troops were telling them they “were going to take back the Chosin Reservoir but everyone more or less pooh-poohed the idea,” recalled Capt. Ed Stamford, a Marine forward air controller who was attached to Faith’s Army battalion so he could coordinate support from Marine aircraft. “They couldn’t take it from us.”

On the same day, Gen. Almond was being briefed on the operations of the 7th Marines. “I already know all this,” he interrupted. “Where’s your intelligence officer?”

Capt. Donald France stepped forward. Almond asked him, “What’s your latest information?”

“General, there’s a shitload of Chinamen in those mountains,” France bluntly told him.

Almond later would insist that the Marines’ chief of intelligence had not seen a threat, stating that he’d been briefed on November 26 that “the G-2 of 1st Marine Division did not give the enemy an offensive capability in the Chosin Reservoir area.” This is shameless quibbling on the part of Almond, because the record is clear that the Marines were reporting substantial columns of Chinese forces moving through the countryside. Almond here is hiding behind the point that the Chinese appeared to be moving north and so were not attacking. Rather, as Gen. Smith correctly feared, they were maneuvering to draw the Marines northward into a trap.

Nor was Maj. Gen. Charles Willoughby, MacArthur’s intelligence chief, crediting any talk of a looming clash with Chinese forces. When the Marines started moving north, they ran into a Chinese force and captured fifty of them. “Those aren’t Chinese soldiers,” Willoughby said. “They are volunteers.” No, Almond responded, siding with the Marines. They have been interviewed, and they say they are regular troops. He invited Willoughby to come look at them. “That’s a Marine lie,” Willoughby responded.

Willoughby was an unusual character. Born in Germany, probably under the name Adolph Weidenbach, he changed his name after coming to the United States before World War I. By 1951, Willoughby had served MacArthur continuously for ten years, the only senior subordinate to do so. Like MacArthur, he enthusiastically dabbled in politics while in uniform, lobbying Congress in the late 1940s, for example, to extend the hand of friendship to Spain’s Fascist leader, Generalissimo Francisco Franco. He persisted in this even after Omar Bradley, then Army chief of staff, told him in writing to desist. (The same year, Robert McCormick, the right-wing publisher of the Chicago Tribune, wrote to Willoughby that he had confirmed with the American ambassador to France that “it is the Jews who are keeping us from recognizing Spain.” McCormick added, “I was told Mrs. Harriman is a Jewess but doubt this. I met her some time ago and saw no indication of it.”)

Not long before the Chinese attack, Willoughby, despite his role as the chief intelligence officer for the American military in the Far East, was busying himself lobbying Congress. He took time to write to Sen. Owen Brewster of Maine “to congratulate you and the able GOP management in obtaining a magnificent and highly suggestive victory in the recent elections. I hope this trend will continue in the future.” He lauded the work of Brewster’s political ally, Sen. Joe McCarthy, and applauded the Republican victory in the midterm elections as “a repudiation of the Administration’s Far Eastern policy.” In January he sent a fan note to McCarthy himself, saluting the Wisconsin Red hunter as “a lone voice in the pinco [sic] wilderness.” A few months later, at a dinner in Tokyo, Willoughby would propose a toast “to the second greatest military genius in the world—Francisco Franco.” MacArthur chuckled at such talk, referring to Willoughby as “my pet fascist.”

While Willoughby was working the Congress on behalf of Franco, the Chinese, more focused on the task at hand, were concentrating around the Chosin Reservoir. On the night of November 27–28, Chinese soldiers attacked Faith’s outpost and quickly worked around the ends of his incomplete, horseshoe-shaped perimeter. “One minute we were planning an attack,” recalled Capt. Erwin Bigger, one of Faith’s company commanders. “The next, we were fighting for our lives in a situation where we knew little of what had hit us.”

In the middle of the night, Capt. Stamford, the Marine air controller attached to Faith’s Army force, heard gunfire and then some nearby “chattering.” The poncho serving as a door to his bunker was pulled aside to reveal the fur-rimmed face of an enemy soldier, who tossed a small hand grenade his way. He survived the blast, but many other soldiers did not make it through the night. The two Army encampments along the east side of the reservoir took heavy casualties that night and were cut off by roadblocks not only from each other but from the Marines to the south. The isolated U.S. Army unit was being hit by the 80th Division of the People’s Liberation Army.

Despite the Chinese assault, the next afternoon, Almond landed at the forward headquarters of Faith and MacLean, and ordered them to get on the ball. “We’re still attacking, and we’re going all the way to the Yalu,” about seventy-five miles to the north, he told them, according to an official Army history. “Don’t let a bunch of Chinese laundrymen stop you.” Never was such racist advice so ill-advised. When Faith reported that his battalion had been attacked by parts of two Chinese divisions, Almond exploded, telling him that “there weren’t two Chinese divisions in all of Korea.” The only opposition Faith was facing, the general reassured him, was from Chinese stragglers fleeing north. Almond also told Faith that it had been a command failure not to have occupied the high ground. “Faith agreed,” he recalled. Almond pinned the Silver Star, a high decoration, on three soldiers, including Faith. “After the helicopter carrying General Almond left the area, I saw Colonel Faith rip the medal off his uniform and throw it on the ground,” recalled Staff Sgt. Chester Bair.

The regiment was about to be smashed head-on by a full Chinese division. Both of the commanders Almond had been exhorting would be dead within three days. By the next afternoon, on both sides of the reservoir, a total of four U.S. Army and Marine regiments were isolated and besieged. Alarmed by what it was hearing, the Joint Chiefs of Staff sent an inquiry to MacArthur, asking whether his units were overly exposed. MacArthur coolly reassured Washington that he had ordered Almond not to let units become isolated. At any rate, MacArthur soothed, “While geographically his elements may seem to be well extended, the actual conditions of terrain make it extremely difficult to take any material advantage thereof.”

Col. MacLean, the regimental commander, was killed early in the fighting as he approached a group of soldiers he thought were his but who were actually Chinese. The two other battalion commanders present were seriously wounded, so command of the cutoff Army units on the east side of the reservoir devolved upon Faith. An Army tank unit located a few miles to his south made several attempts to break through to him, but all failed. Unfortunately, and quite negligently, this crucial fact was not communicated to him at the time.

This was the moment when good generalship could have made a lifesaving difference. Faith needed a senior officer to step in and guide him, to coordinate his movements with supporting aircraft, to establish better communications, to find out what help could be given in other ways, and generally to help him organize his withdrawal and also use rank to summon the formidable assets of the U.S. military. None of this happened. Faith was not well served by his superiors. His division commander, Maj. Gen. David Barr, helicoptered in to visit him on the morning of November 30. “The situation was much more serious than he realized,” Barr recounted three months later in a lecture at the Army War College. That appears to have been all the advice that Barr brought. It is amazing, Maj. Berquist later wrote, to consider “that MG Barr did not coordinate a breakout attempt with LTC Faith right at that moment. MG Barr knew the true extent of the situation and only he, not LTC Faith, was in a position to coordinate anything.” Like Faith, Barr had been a staff officer in World War II, not leading troops in combat. What Faith needed at this point was not a pat on the back and some demoralizing assessments but concrete support from Barr and Almond in the form of coordinating his retreat with an attack from Army tanks to the south. Barr’s assistant division commander, Gen. Hodes, a seasoned combat veteran, was nearby and easily could have been put in charge of the effort—but wasn’t.

The situation continued to deteriorate. “Nothing was working out,” recalled PFC James Ransone Jr. “We were being shot up bad. We were just in a terrible situation. We were being annihilated.”

That evening brought the most determined Chinese attack so far. At three in the morning, Chinese soldiers overran part of the Army perimeter, giving them devastating control of a small hill overlooking the entire Army encampment. Faith’s position had never been good, but now it was untenable. The following morning, after three days of intensifying Chinese attacks, running low on ammunition, and with wounded dying from lack of medical care, Faith and the regiment set out to try to make it four miles south, to where they believed—incorrectly—that friendly lines began. “They had been fighting for over eighty hours in below zero weather,” observes Berquist. “Few had had much sleep or much to eat,” because what food they did have was frozen. “Dead and wounded soldiers were everywhere and wounded soldiers who could not move froze to death.” The dead performed a final posthumous service, becoming the supply depot for the living, who stripped the corpses of their comrades for clothing, weapons, and ammunition.

What could go wrong did. Faith did not know it, but the temporary Army outpost he was aiming for had pulled out, so safety was not four miles away, as he thought, but seven miles away, at Smith’s Marine base at the southern end of the reservoir—and it had fewer troops than Faith had. As the column of about thirty trucks formed, each carrying fifteen or twenty wounded, a barrage of Chinese mortar shells wounded several key leaders. Marine aircraft appeared overhead to provide air support. The column began to creep southward, only to come under Chinese rifle fire almost immediately. Lt. James Mortrude, who was in the lead vehicle, recalled, “We had proceeded only a short way beyond the perimeter when a furious burst of enemy automatic weapons fire drove me and the gunner down behind the shield of our open turret.” A call went out for air support, only to result in the lead Marine aircraft dropping napalm on the vanguard of the Army column. Mortrude was able to crouch down in the turret and let the wave of flame pass over him, but others were not so fortunate. Maj. Hugh Robbins, lying wounded in the bed of a truck, ducked as the bomb hit, then peered through the slats of the truck to glimpse about fifteen soldiers enveloped in fire. “Looking back up I could see the terrible sight of men ablaze from head to foot, staggering back or rolling on the ground screaming,” he recalled.

“It was terrible,” recalled Pvt. Ransone. “Where the napalm had burned the skin to a crisp, it would be peeled back from the face, arms, legs. It looked as though the skin was curled like fried potato chips. Men begged to be shot.” One officer, epidermis burnt black, asked a soldier for a cigarette and then walked into the frozen distance, never to be seen again.

The column moved on at less than walking speed as the trucks were raked endlessly with fire from Chinese rifles and machine guns. Some of the wounded were hit two or three more times while lying in the back of a truck. Drivers, sitting in the left sides of their vehicles, were particularly vulnerable, as the column was heading south and was overlooked by a parallel ridge to the east—that is, on the drivers’ side of the convoy.

Two hours into its crucifixion, the convoy encountered a nasty surprise: The bridge leading across a stream had been blown. No one had thought to ask the Marine pilots flying overhead to report to them on the state of the road. At this point, the M19 vehicle in the lead, carrying a set of powerful .50-caliber machine guns that could scythe down attackers, ran out of ammunition. But it still made itself useful by winching the trucks through the streambed adjacent to the destroyed bridge. This was a one-by-one process that consumed two hours of daylight. The M19 then ran out of fuel. Both these outages might have been prevented by better communication, coordination, and support between Faith and his superiors. While the American convoy was tugged across the stream, the Chinese enemy used the time to move south and take up positions along the hillside the Americans would next have to ascend. When the convoy resumed moving, some of the soldiers who could walk began running away, mainly heading downhill, out to the ice of the reservoir, where they had a chance to walk south to the Marine outpost at the southern end of the reservoir. Among the first to run, survivors reported, were those assigned to defend the rear of the column.

At the top of the hill, the convoy hit a Chinese roadblock. Soon the winter evening began to fall, which meant the Americans would lose their air support, the only major weapon remaining to them. Discipline was eroding rapidly. Soldiers and officers sent up a hill to flank the roadblock declined to assault the Chinese and instead continued down its other side, eventually angling out to the ice of the reservoir. One exception was Capt. Earle Jordan, who assembled a group of ten soldiers who fought their way toward the roadblock, only to run out of ammunition when they got to it, so they continued their assault “by yelling, shouting and making as much noise as possible,” according to historian Roy Appleman.

About one-third of the sixteen thousand men in the U.S. Army’s 7th Division were Koreans who had been pulled in from the streets, hastily trained, and put into American units to round them out. This was an ill-conceived plan that impeded the units when they were under pressure. Faith found two of his Korean soldiers under a truck, apparently trying to hide by tying themselves to its undercarriage. He pulled them out and executed them with his .45. “It was a sad and outrageous moment,” historian Martin Russ comments. “Faith did not shoot any of the American soldiers who were equally demoralized—and who had received far better training than the hapless ROKs.”

Whatever Faith’s shortcomings, he was still trying to provide leadership. A few minutes later, when he was struck in the chest by grenade fragments, all semblance of organization went with him. “After Colonel Faith was killed, it was everyone for himself,” recalled Sgt. Bair. “The chain of command disappeared.” The column moved on about another quarter-mile, only to run into another roadblock. Those who survived the massacre were primarily those who now cut to the west and walked or even crawled south on the ice toward Marine lines. When three trucks loaded with wounded were abandoned by their drivers, a fourth truck tried to push them aside and wound up overturning them down the hillside. “Wounded men inside were spilled and crushed,” an official Army history relates. “The frantic screams of these men seemed to Lieutenant [James] Campbell like the world gone mad.”

That was the end of the convoy, which now was stalled and defenseless. Hundreds of wounded were left behind, lying stacked in trucks. Chinese soldiers trotted along the column tossing white phosphorus grenades into the vehicles, burning to death many of those who had not already been killed by the cold. Still, some survived: A Marine pilot who flew low over the column the next day reported that he saw some wounded trying to wave.

Out on the frozen reservoir, Gen. Smith recalled, “some of these men were dragging themselves on the ice, some of them had gone crazy and were walking in circles.” Many of the soldiers were rescued by Marine Lt. Col. Olin Beall, the crusty commander of the 1st Motor Transport Battalion, who, on his own initiative, over three days, repeatedly took five Marines and a Navy corpsman in jeeps out onto the ice, where they collected 319 Army survivors, almost all of them wounded, frostbitten, and disoriented. The grizzled Beall had enlisted in the Marines at the outset of World War I but left the Corps in 1922 to try his hand at minor league baseball. After a season in which he posted an unimpressive 0–1 record as a pitcher for the Class D Blue Ridge League’s Martinsburg, West Virginia, Blue Sox, he reenlisted and eventually became an officer. (His Blue Sox teammate Hack Wilson did better, with a 1922 batting average of .366 and thirty home runs in eighty-four games. Wilson eventually went on to the New York Giants and then into the Baseball Hall of Fame.)

Operating under the eyes of Chinese riflemen who were sometimes just one hundred feet away but generally did not fire at them, Beall and his men attached sleds to their vehicles to pull stacks of the wounded. After two days of rescue work, Beall finally arrived at the charred remains of the Army convoy and inspected its hulks, looking for more survivors. He counted about three hundred dead but found no one still breathing. Ultimately, the 31st Regimental Combat Team, which included Faith’s battalion, lost all its artillery pieces and vehicles and left behind many of its wounded soldiers and all of its dead. Overall, the casualty rate for the 3,288 men of the 31st Infantry Regiment was an astonishing 90 percent.

The Marines fed the survivors hot soup and evacuated the seriously wounded by air; then they took the 358 men deemed capable of fighting and put them into a provisional battalion, plugging them into their perimeter. The Army officer put in charge of them later suffered a mental breakdown, according to Gen. Smith. At this point, the generals, so sluggish a few days earlier, sprang to action. All the far-reaching, powerful tools of the U.S. military establishment, seemingly so unable to help these men when they were besieged, now came to their aid. Within twenty-four hours of being shot up in the hellish convoy, some of the soldiers were sleeping in the clean sheets of Army hospital beds in Japan.

Less noticed in the debacle, and not much mentioned by the Marines subsequently, was the fact that, by getting in the way of the Chinese attack, the Army regiment may have bought a day or two of precious time for the 1st Marine Division. Without Faith’s last stand, the Marines might not have been able to hold the key junction of Hagaru-ri, at the southern end of the reservoir, where they built an airstrip and which they held with a small contingent while the two Marine regiments on the far northwest side of the reservoir fought their way back down to them. But this does not excuse the utter failure of the Army generals in the chain of command: Hodes, the seasoned assistant division commander, who might have stepped in; Barr, the division commander, who should have; Almond, the corps commander, whose arrogance made matters worse; Willoughby, the intelligence chief general who refused to recognize the reality of a Chinese intervention in the war; and, most of all, MacArthur, the top commander, who had insisted on the harebrained drive to the Yalu through the Korean winter. In World War II, several of these men would have been removed for their poor leadership at Chosin. In Korea, only Barr was. MacArthur’s firing, when it came a few months later, would be for a different reason.