6

‘De-financialising’ the UK Economy:

The Importance of Public Banks

The performance of the UK economy during the decade since the outbreak of the great crisis of 2007–9 has been mediocre in terms of growth, income and employment. Working people have borne the brunt in terms of wages, welfare services, housing, education and so on.1 The crisis, in which private banks played a major role, resulted from the transformation of the UK economy in recent decades that has lent extraordinary prominence to finance. The UK economy has become ‘financialised’, with rising volumes of private debt and extensive penetration of finance in economic and social life.

Since the crisis, however, UK finance has lacked the expansionary drive of the previous period, and private debt has not grown with nearly the same vigour as in the previous decade. At the same time, public debt has risen substantially as the government has intervened to support the financial sector, and especially to protect the private banks. Financialisation has acquired a public aspect due to government policies which have also shaped the poor performance of the economy.

The UK needs a significant change in economic policy to benefit working people by gradually transforming the economy in the direction of higher incomes and better employment. ‘De-financialisation’ would be necessary to create an economy serving and empowering working people. A vital step in this regard would be to create public banks that could serve the investment and consumption needs of the UK.

A Crisis of Financialisation in 2007–9

The global crisis of 2007–9 sprang out of the US financial system, subsequently engulfing the UK economy and its financial system. The crisis had its roots in the financial expansion of the previous years when a housing bubble took place in the US, but also in the UK. It was fed by extraordinary growth in household debt and was sustained by complex financial operations, including securitisation of mortgages and other assets.2

The main culprits in the US were commercial banks but also ‘shadow banks’, that is, enterprises that do not take deposits but instead borrow in open markets in order to make loans. The ‘shadow banking’ sector in the UK is much smaller, and the main culprits of the bubble were commercial banks, including the old building societies which had become banks in the 1980s and 1990s.

The bubble was pricked in the US in the summer of 2006, when many of those who had obtained mortgages proved unable to keep up payments. They typically belonged to the poorest sections of the US working class, and often were black or Latino. Since they could no longer make regular mortgage repayments, the securitised assets based on their mortgages could no longer deliver the contracted payments to their holders. The assets had become ‘toxic’.

From that moment onwards events unfolded catastrophically for banks and ‘shadow banks’. Since securitised assets had become problematic – indeed they were getting worse and worse – financial institutions could no longer borrow by using these as security. Given that they could not borrow, it followed that they had no liquid funds to lend, and so the financial markets gradually went into an extraordinary contraction as liquid funds became increasingly scarce.3

The liquidity shortage eventually reached panic dimensions and people began to withdraw their deposits, while owners of liquid money capital also began to withdraw it from banks. For the first time in decades the UK witnessed a traditional bank run when, in the autumn of 2007, depositors queued outside branches of Northern Rock, a building society that had become heavily exposed to the bubble. Even worse for the banking system, however, was the ‘silent bank run’ of withdrawals by large owners of money capital. At the same time, the solvency of banks was put in doubt as they began taking losses on mortgage-related assets.

The combination of liquidity and solvency pressures brought the crisis to a peak in the summer of 2008, marked by spectacular collapses of giant banks in the US. Huge UK banks also faced tremendous pressure, none more than the Royal Bank of Scotland, which had played a pivotal role in the excesses of the preceding bubble. There had not been a financial crisis of this type and magnitude since the great collapse of finance in the early 1930s.

The intervention of the government in both the US and the UK was, however, dramatically different from the interwar years. In its absence the disaster that had befallen the financial system would have reached inconceivable dimensions. Thus, central banks began freely to provide liquidity to assuage the extreme shortage of liquid funds; Treasury departments began to supply banks with capital to lessen the risk of insolvency; bank deposits were guaranteed. In the UK, banks were placed under government ownership, most prominently the Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) but also Lloyds Bank. Even in the US, bank nationalisation was seriously considered in 2009, though it did not come to pass. Eventually state intervention stabilised the financial system.

The great crisis of 2007–9 represents a systemic failure of contemporary private banking and finance. It is a failure that has had dramatic effects on the UK and other mature economies in the years that followed, marked by deep recession, weak recovery, tremendous loss of income and sustained austerity that has damaged health, education and welfare provision generally. The failure of private finance, moreover, has demonstrated its profound dependence on the state. This is a fundamental point in considering policy towards the financial system today.

An even more important point is that the crisis of 2007–9 reflects the deep structural weaknesses of contemporary capitalism as finance has grown relentlessly. Since the late 1970s the economy of the UK can be aptly described as having steadily ‘financialised’, a term that is now widely deployed in social sciences. The financial sector has become extraordinarily important in a variety of ways, some of which are discussed below.4

The turmoil of 2007–9 was a crisis of financialised capitalism in terms of both its origins and its subsequent impact on the economy and society of the UK. The years that have followed have witnessed the stabilisation of the economy through the intervention of the state, but they have not brought a reversal of financialisation. Rather, financialisation in the UK – and the US – has come to depend more heavily on government. This is the standpoint from which policy relative to the financial system ought to be considered.

Ten Years On: Financialisation Relies Heavily on the State

The UK has one of the largest financial systems in the world; the UK system is also very international, and the City of London is a major global centre for financial transactions.5 London is the true financial centre of Europe, with strong participation by international banks and other financial institutions. The prominence of finance in the UK has increased greatly as the economy has become financialised during the last four decades. Consider briefly some evidence regarding both the evolution and the current state of UK financialisation.

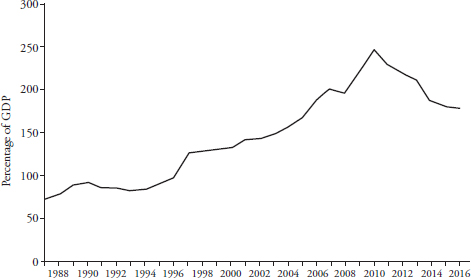

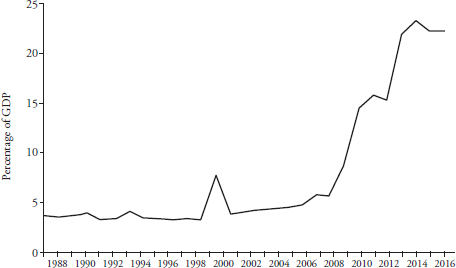

One indicator of the relative size of finance is given by the total assets of UK banks relative to GDP, including both domestic and foreign banks resident in the UK, as is shown in Figure 6.1.6 Even though this indicator leaves much of the financial system out – for instance the assets of hedge funds, pension funds and insurance companies – it is still informative since the banks are by far the most important element of the financial system.

Figure 6.1

It is clear that banking has grown remarkably during the last four decades, with rapid growth commencing in the early 1980s and peaking at the time of the crisis in 2007–9. Since the crisis, however, banking has failed to grow with similar dynamism, for reasons discussed below. Its relative decline is an important factor in planning policy towards finance.

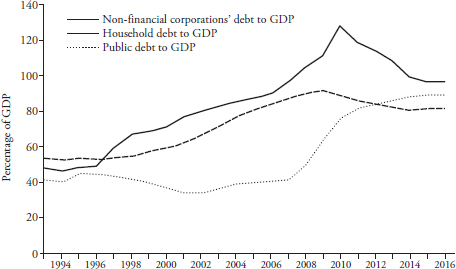

The general growth of bank assets, however, implies that debt has been growing in the UK economy, since bank assets are basically loans. Financialisation has brought tremendous growth of debt in the UK, the composition of which is also revealing. To examine the trajectory of debt, it is useful to split total debt into the debt of, respectively, non-financial corporations, households, financial corporations and the government, as is shown in Figure 6.2.

Figure 6.2

Total debt has grown substantially relative to GDP in the years of financialisation, but note that the growth of private debt has been generally arrested since the crisis of 2007–9. Specifically, although the debt of both the corporate and household sectors has witnessed strong growth historically, it has tended to decline in relative terms for both since 2007–9. In contrast, public debt, which has generally been rather stable or declining, has escalated since the crisis. UK financialisation has begun to acquire a distinctly public aspect.

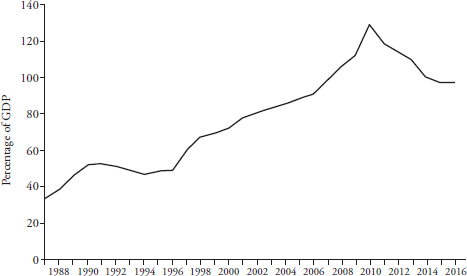

It is worth considering the corporate and household sectors more closely to obtain a better view of the trajectory and the content of financialisation. Thus, Figure 6.3 shows the total credit provided to the UK corporate sector – productive and commercial enterprises – by the financial system.

Figure 6.3

Bank credit to non-financial corporations has expanded systematically throughout the period of financialisation, peaking in 1991 and 2002, while reaching an overall peak in 2009. In 1991 and 1992, credit resumed its sustained expansion after a short period of contraction or stagnation. However, since 2009 bank credit to productive enterprises has declined precipitously and has not shown a sustained tendency to rise. Household debt presents an equally striking picture, as shown in Figure 6.4.

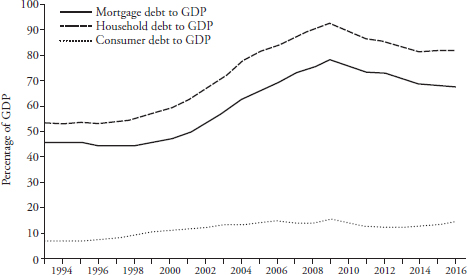

Figure 6.4

Household debt grew substantially in the decades of financialisation, mostly driven by mortgage rather than consumer debt, especially in the 2000s. However, since the crisis mortgage debt has fallen significantly relative to GDP and has shown no signs of rising in a sustained way; consumer debt, on the other hand, has gradually recovered.

Financialisation has been marked by drawing households into the realm of the financial system, even more than by the expansion of credit to the productive sector. Indeed, the large enterprises of Britain and other countries have been awash with money capital in recent years, which they have not been investing but rather deploying in financial operations. Households have been drawn into the financial system mostly through mortgage provision, but consumer debt has also been significant. It is important to note that financialisation has also affected household assets, i.e. pensions, insurance and so on, which have also been drawn into the private financial system.

The financialisation of households has been a characteristic feature of the last four decades in the UK, with private finance penetrating personal and family life. The needs of households for housing, education, transport and so on have become fields of profit-making for financial institutions. Key to this development has been the restriction or withdrawal of public provision in these fields, together with downward pressure on real incomes.

The intervention of the state in the course of the crisis of 2007–9 can now be understood in greater detail. The main concern of the government was to protect the exposed financial system and to prevent a collapse of the basic structures of financialisation. First, the Bank of England provided abundant liquidity to ease the shortage, thus tremendously expanding its balance sheet, as shown in Figure 6.5. Second, interest rates were driven practically to zero, thus allowing banks to obtain funds cheaply. Third, some of the largest banks were nationalised to prevent collapse, most prominently the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Figure 6.57

State intervention has rested on issuing large volumes of public debt by the government, above all to finance the generation of liquidity by the Bank of England. Thus, ten years since the outbreak of the crisis, the British state has substantially increased its indebtedness, while the private sectors of the economy have been reducing theirs, as is shown in Figure 6.2. The Bank of England has, meanwhile, come to tower above the financial system and the economy more generally. Needless to say, increased public debt and liquidity have not supported public spending on investment, welfare, wages for civil servants and so on. On the contrary, while supporting the financial system, the British government has applied relentless austerity in the forlorn hope of limiting public debt.

The cost of austerity could be gauged by declining quality of welfare provision, especially in health, but also by rising indebtedness for students. Austerity has had the further cost of depressing aggregate demand, thus preventing a strong recovery of the economy; rates of growth for the British economy have averaged around 2 per cent since 2009, the weakest period of growth since the oil crisis of 1973–4. Recessionary pressures have been made worse by the lack of investment by enterprises, matched by declining credit by banks, as is shown in Figure 6.3. The weakness of the economy since the great crisis has also been reflected in poor growth of productivity. Finally, employment has gradually recovered, but the jobs created have generally been poorly paid.

Not surprisingly, the financial system has continued to face difficulties since 2007–9. Depressed demand and weak income growth together with the huge backlog of mortgage debt have led households to reduce their debt in relative terms, as shown in Figure 6.4. Moreover, enterprises have generally not been investing and have thus also reduced their relative exposure to banks. Low interest rates and reduced financial transactions in general have put additional pressure on financial profitability for several years.

In sum, during the decade since the outbreak of the crisis the UK has been drifting. Financialisation has been marking time, while becoming heavily reliant on state support. The performance of the economy in terms of growth, income, productivity and employment has been deeply problematic. At the same time, the tendency of finance to generate bubbles and to create instability has far from disappeared. Low interest rates and abundant liquidity provided by the state have gradually created conditions for speculative growth in the stock market in both the US and the UK, particularly in 2016–17. The financial sector has gained some leeway and boosted its profitability, but the final outcome of stock market growth remains to be seen.

De-financialising the UK

A general change in policy towards the financial system is called for, if things are to improve for the British people. The ‘de-financialisation’ of the UK economy ought to be placed on the agenda. Moreover, the Brexit vote in 2016 has unexpectedly created opportunities to take steps in that direction.

The implications of the UK leaving the European Union in 2019 are far from clear for the British financial system, and they are not directly relevant to this chapter. However, there is little doubt that banks will be forced to rebalance their domestic and international activities. It is likely that some international financial institutions will move part of their activities elsewhere, although the comparative advantages of the heavy concentration of financial processes and skills in London would be hard to replicate in other European cities. It is also possible that UK banks would face extra costs in operating elsewhere in Europe, which might affect some of the large UK banks, including Barclays and HSBC.8

In this context there is the possibility of intervening decisively to rebalance the financial sector, thus setting in train a process of ‘de-financialisation’. Vital to it would be transforming the banking system. To be specific, policy changes that placed the interests of working people at the forefront should seek to create public banks. They should also seek to create special-purpose public financial institutions that could serve the investment and consumption needs of contemporary Britain.

Public ownership of banks and other financial institutions has been far from rare in the decades of financialisation. Public banking, for instance, has remained very significant in Germany throughout the last three decades, including a large long-term investment bank (KfW). During the crisis the UK government took majority stakes in RBS and Northern Rock, plus a minority stake in Lloyds-HBOS. The aim was to rescue these banks, subsequently to return them to full private ownership. This has already been done with Lloyds-HBOS, but the weakness of RBS was so great that the UK government has retained a strong majority stake.

It is unfortunate that the UK government has consistently refused to take over the actual management of the banks it placed under public ownership. They could have been operated in a public spirit aiming to support the performance of the economy as well as facilitating ‘de-financialisation’.

For one thing, public banks could become major providers of commercial banking functions to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) as well as to households. Steady provision of commercial credit to SMEs and households could sustain aggregate demand, support employment and boost investment. Without neglecting the monitoring and screening functions over lenders, public banks could in principle regulate the flows of individual (and SME) credit to achieve socially set objectives.

For another, public banks and special-purpose financial institutions could support the provision of long-term development credit. With secure financing backed by the state, public banks would be able to contribute to the long-term rebalancing of the UK economy by reducing the predominance of finance. The rebalancing would include areas of advanced technology and high productivity growth. It could also include supporting ‘green’ activities, such as non-fossil fuel forms of energy, less reliance on private cars, raising the energy efficiency of private homes, reducing industrial pollution and so on. Generally speaking, these aims require major public investment, which public banks would be able to finance.

As for households, public banks could provide credit for housing and education as well as for general consumption. Such credit would presuppose regular repayment at publicly determined rates of interest, which would vary according to the objectives of social policy. Public banks could certainly adopt the techniques of information collection for income, employment and personal conditions, while still deploying credit scoring and risk management. Their role in providing such credit, however, would be heavily circumscribed by the revitalisation of public provision in these fields, especially with the construction of large numbers of new homes and the abolition of student fees for universities. These would be crucial steps in ‘de-financialising’ the life of working people in Britain.

A spirit of public service would be vital to ‘de-financialisation’. Finance has been one of the least transparent sectors of contemporary economies, with disastrous results. Establishing public banks would be more than mere nationalisation, and certainly not the simple replacement of failed private managers by state bureaucrats. Their remit would be set socially and collectively, imposing transparency on decision making and full accountability to elected bodies. Public banks could thus become an effective lever for the systemic regulation of finance, facilitating controls over the activities of private banks. Finally, the technological revolution of the last few decades, with the rapid growth of data collection and processing by banks on a massive scale, offers further potential to coordinate banking activities on a public basis. The potential to support the democratic management of the economy has correspondingly increased.

These are some of the policy issues relating to finance that should be discussed in detail in Britain. With sufficient political will, the UK could make considerable progress in the coming period, potentially opening a path for the rest of Europe.