8

Beyond the Divide: Why Devolution

Is Needed for National Prosperity

The UK Has a Problem with Its Regional Economies

The UK has a regional economic problem without parallel in the developed world. London and the South East are responsible for most of the UK’s economic output, and London is considerably more productive than the rest of the UK.1 The UK is now the most regionally unequal country in Europe, and there is emerging evidence that London and its hinterland are starting to ‘decouple’ from the rest of the UK – that is, not acting as an engine for the country but becoming a separate economy.2

These economic issues have also begun to manifest themselves in declining socio-economic outcomes. For example:

•In all the English regions outside of London, average incomes are between 10 and 20 per cent below the UK average.

•The unemployment rate in the UK varies from 3.3 per cent in the South West to 5.1 per cent in the West Midlands.

•Healthy life expectancy at birth is 66.1 years for men and 66.3 years for women in the South East, compared to 59.7 for men and 60.6 for women in the North East.

•The proportion of people with no qualifications averages 10 per cent across the North and the West Midlands, compared to 6 per cent for London, the South East and the South West.

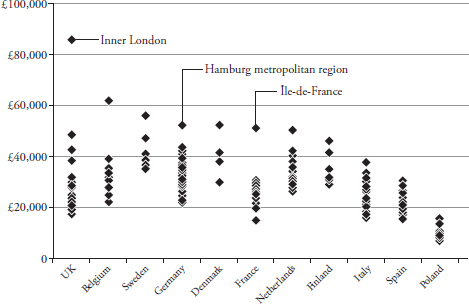

Figure 8.1

Source: Data from Eurostat, ‘Gross domestic product (GDP) at current market prices by NUTS 2 regions’ (Eurostat 2016)

There are complex reasons for this gap, many of which relate to structural changes in the economy over many decades. Since the Industrial Revolution, the UK has transformed from an economy based on mining and other forms of extraction, through to heavy industry, on to light industry and now to services. These shifts have partly been prompted by the changing face of globalisation and advances in technology, which have led to labour in these industries being outsourced, automated or simply made redundant in the modern world.3 The long-term transformations and frequent economic shocks associated with globalisation have tested the resilience of different regions: some areas have had the economic diversity or specialism they need to adapt better than others; other places have suffered long-term decline.4 For the English regions where much of the UK’s manufacturing was located, this shift has been particularly painful. Meanwhile, the continued growth of financial services in London has accelerated its integration into the global economy.

However, the causes of such change cannot simply be reduced to the impersonal ‘forces’ of globalisation. Globalisation itself has not been a neutral, irresistible change associated with human progress; its shape and direction are determined by a specific set of policy decisions. There is nothing ‘natural’ about this geographical pattern of economic success. Other countries and regions have responded to changes in the global economy and seen very different results – the UK’s regional imbalance may be unique, but the successive challenges the country has faced over the last century are very similar to those faced by overseas nations.5

One of the most significant differences between many other countries and the UK – and England in particular – is that other countries have had strong subnational governments delivering regional economic policy and interventionist industrial strategy. In the UK, central government makes almost all of these decisions, and does so under the strong influence of the financial sector in the City of London.

The Central State Has Been a Major Cause of Our Regional Problem

While other countries have reaped the benefits of regional government, the UK has continued to experiment from Whitehall, which has shown little interest in tackling the UK’s regional problems. Central government has not only failed to tackle rising regional inequality – its economic policy has actively favoured London. The emergence of a powerful City–Bank–Treasury nexus in the capital has had far-reaching implications, and has led to economic policy in the UK being consistently geared towards boosting our financial sector at the expense of regional exporters.6

THE GROWTH OF THE UK’S FINANCE SECTOR HAS LED TO THE EMERGENCE OF A FINANCIAL DUTCH DISEASE

Since the 1980s, the UK has had a large and persistent current account deficit.7 The current account deficit reached a peak of 6 per cent of GDP in 2017 – one of the largest of any advanced economy.8 Macroeconomic theory would suggest that interest and exchange rates in the UK should adjust to bring about a reduction of the current account deficit, but up until the vote to leave the European Union in 2016, sterling remained remarkably strong.

This puzzling pattern is explained by the UK’s ability to attract financial flows from overseas due to our large financial sector. Our current account deficit – primarily the result of a trade deficit – is financed through an equally large surplus on our financial account. The attractiveness of UK assets to international investors over the last forty years can be explained by a combination of low global interest rates and asset price inflation in the UK. High levels of lending in the domestic economy, encouraged by financial deregulation in the 1980s, have pushed up the prices of UK assets, particularly housing. Asset price inflation has increased the amount of capital flowing into the UK via the financial account, much of which has been transformed into debt for UK consumers. These capital inflows are what have sustained the high value of sterling, even in the face of a large and growing current account deficit. This model ultimately came to a head in the crisis of 2007, which has had a much greater lasting impact on the UK’s regions than on the financial centre in London.

This model amounts to the emergence of a form of financial ‘Dutch disease’ in which an overvalued currency, induced by the growth of the finance sector, negatively impacts other economic sectors and therefore those regions where finance is less significant.9 Finance and related business services grew from 16 per cent of economic output in 1970 to 32 per cent in 2008, while manufacturing shrank from 32 per cent to 12 per cent over the same period.10

Dutch disease has manifested itself in the UK in two ways. First, with a strong currency boosting purchasing power the UK economy has become extremely reliant on imports for consumption, while our manufacturing exporters have found it more difficult to compete and retain a domestic market share. This means that devaluation generates significant cost-push inflation, of the kind that the UK has experienced since the Brexit referendum.11 Second, over time the strong pound has become ‘locked in’, as manufacturing sectors have developed a reliance on relatively cheap imported inputs. Path dependencies have now developed in UK manufacturing that make it harder for the sector to take advantage of currency depreciation when it does happen.12

This reduced capacity to benefit from exchange rate depreciations has been evident in the wake of the financial crisis. Between July 2007 and January 2009, the effective value of sterling declined by over 25 per cent. The pound dropped again when the UK voted to leave the European Union: since the vote, the value of sterling has fallen 25 per cent in effective terms.13 This precipitous decline has failed to lead to an improvement in the UK’s current account. In fact, it has catalysed an acute deterioration in the current account deficit, which peaked at 6 per cent of GDP in 2017. Since its low point, the current account has recovered somewhat, but statistics from the first quarter of 2018 show that the trade balance has started to deteriorate again.14

CENTRALISED POLICYMAKING HAS REDUCED REGIONAL ECONOMIC RESILIENCE

Successive governments have failed to address this issue because policymaking has come to be dominated by a ‘City–Bank–Treasury’ nexus, in which the interests of finance in London are prioritised over those of manufacturers in the regions. Monetary and fiscal policy have, since the 1980s, exacerbated the problems associated with the UK’s Dutch disease rather than ameliorating them:

•The new economic model of the 1980s focused on low inflation, stable exchange rates and low public spending. A steep rise in interest rates crippled British industry at the very moment it required support and investment. The deregulation of financial markets catalysed the ‘Big Bang’ in London, which contributed to exacerbating a pre-existing ‘Dutch disease’ due to the discovery of oil in the North Sea, which saw a strong pound render what remained of Britain’s exports even less competitive.15 During the recession of the 1980s, manufacturing employment fell by 11.2 per cent, while employment in finance and insurance increased by 3.9 per cent.16

•The Labour government of 1997 responded to the clear regional problem that had developed by the early 1990s by increasing public sector employment. This helped to improve output and employment, but also increased public sector spending without providing a sustainable basis for long-term employment. As interest rates continued to increase, monetary policy worked in opposition to these measures, with a former governor of the Bank of England stating that ‘unemployment in the North East is an acceptable price to pay to curb inflation in the South’. The North and the West Midlands saw their share of output from manufacturing decline from 24 and 27 per cent of regional gross value added (GVA) to 15 and 13 per cent respectively. Financial services output increased at double the rate of GDP growth and the proportion of GVA accounted for by manufacturing halved.

•The recent Conservative-led governments have since constrained public sector employment for the UK’s regions, while again protecting it in London. The Conservatives have argued that the public sector is ‘bloated’ and needs to be cut back, with large parts of the country ‘dependent’ on public sector spending. Thanks to the structural decline of the previous decades, these areas are generally found in the North and the West Midlands. In the North, public sector employment has fallen by 302,000 (18.7 per cent), while in London it’s fallen by only 91,000 (11 per cent) since 2009/10.

•The current Conservative government cites recent labour market statistics to indicate its positive record on job creation – across the UK, unemployment is the lowest it has been in decades. But this headline figure disguises both the regional variation within this figure, and the precarious nature of the employment that has been created. While unemployment in the UK as a whole is at 4.2 per cent, it is 5.1 per cent in the West Midlands, next to 3.3 per cent in the South West. Much of this employment is insecure, low-skill and poorly paid.17

During this time there has been some devolution and regional policy: since 2000 Northern Ireland, Scotland and, to a lesser extent, Wales have had economic power devolved to their national assemblies and parliaments. This appears to have borne fruit, with economic affairs spending per head consistently higher than in English regions in recent years, and some economic statistics in these nations are beginning to show relative improvement.18

However, within England – home to 55 million of the UK’s 65 million population – regional policy has failed to gain a foothold. While the devolved nations were getting some real power and democratic legitimacy, the regions of England have remained under the control of Westminster via the regional development agencies. These were intended to be set up alongside regional assemblies to ensure some democratic accountability, but the government has shown little enthusiasm for this arrangement.19 Without constitutional or democratic protection, these fragile bureaucracies were wiped out within months of the new government in 2010.

The high levels of political centralisation in the UK (more specifically England), coupled with the policy capture implied by the immense power held by the finance sector in the City of London, have resulted in a distinctive ‘British business model’, characterised by ‘close government–business relations in finance and the economy and political influence of the financial services sector in the UK’.20 This has meant that the interests of the financial sector have, for decades, been placed at the heart of Britain’s policymaking, and the policy decisions made by successive governments have served to exacerbate the challenges faced by regions outside of London, instead of supporting these regions to thrive in a rapidly changing world.21

More Economic and Fiscal Power Should Be Held in the UK’s Regions and Nations

Devolution to the UK’s regions is the only way to resolve the UK’s severe regional problem. The fundamental problem facing UK productivity is the lack of regional autonomy necessary to mobilise the appropriate players, institutions, knowledge and capital in order to respond to global economic shocks and develop effective responses. While by its nature the effect of devolution is difficult to prove definitively, research has shown how regional economic performance – including resilience to shocks and restructures – is closely related to the strength of governance and the presence of regional institutions.

Fiscal devolution is a challenging but extremely important component of devolution. In the UK, local government raises only 5 per cent of total taxation, placing it among the most ‘fiscally centralised’ countries in the developed world.22 Contrary to suspicions that fiscal devolution will exacerbate these differences, a wealth of research has shown that it tends to engender a ‘race to the top’ and greater equality:

•Fiscal devolution can improve GDP per capita, and is strongly correlated with investment in human and physical capital, as well as education outcomes.

•Regional disparities are reduced in countries where more local spending is financed by local taxes, because sub-central governments are more inclined to spend on economic development.

•Fiscal devolution results in higher levels of equality, improved well-being and improved social welfare.23

Fiscal devolution may be essential, but it will not be achieved easily and needs a long-term solution in order to work. Because of the many decades of underinvestment, parts of the country simply don’t have an economy strong enough to generate the tax revenues required. This means that any fiscal devolution will need to be preceded by a period of ‘pump priming’ by central government funding streams, before taking on greater responsibility. There will also need to be safeguards in place, and some redistribution between regions will always be necessary. Moreover, any new regional institutions must be sufficiently democratic to ensure that the interests of citizens are placed at the centre of a new regional settlement.24 The UK does not lack the capacity to move towards such a settlement, merely the political will.

Conclusions

The UK has a serious regional problem: over generations, successive governments have failed to utilise the economic assets that sit outside of London, and with each economic shock or shift governments have simply doubled down on the capital as the supposed ‘engine’ of the UK economy. This is not simply globalisation running its course: it has been driven by policy decisions.

These decisions have been made almost exclusively by central government. For decades, central government managed and manipulated globalisation in the interests of London and the financial sector. A centralised state has built an economy which has itself become centralised on one city, and far too dependent on one particular sector. With no regional government or industrial strategy, the modernisation of the rest of the country’s economy has been a painful uphill battle. It is clear that our national experiment with centralisation has categorically failed.

To deliver national prosperity, Labour must end its love affair with the centralised state and devolve real power to the regions of England. We will only have thriving regions if central government ends the ‘Whitehall knows best’ approach to economic policy, which has surely been proven to be a mistake. To act as a real counterweight to London, these regional institutions must be afforded real powers, be properly resourced and, crucially, be made democratically accountable to citizens.