11

Debt Dependence and the

Financialisation of Everyday Life

This chapter explores how finance has become deeply embedded in the daily life of many UK households. It begins with a brief outline of finance-led growth, then details how this affects the average household in three distinct ways: (1) decimating long-term cash savings in favour of asset-based welfare, (2) transforming housing into a highly leveraged financial asset and (3) relying on debt for economic participation and as a safety net. The chapter concludes by considering why there continues to be a strategic silence about household debt within public policy when it is clear that current levels of household indebtedness are unsustainable over the long term.

Initially the term financialisation described how the corporate governance priorities of large firms prioritised profit-making through equity markets (stock price) rather than product market competition (price of goods and services).1 Lazonick and O’Sullivan succinctly describe financialisation as ushering in a profound shift in the corporate governance strategies of large firms from ‘accumulate and reinvest’ to ‘downsize and distribute’, which meant routine cuts to labour costs, including wages and pensions, or selling off or closing down whole divisions to realise short-term profits that amplified stock market performance.2 Gradually the term financialisation came to encompass a wider set of economic transformations: from ‘advanced industrialisation’ to finance-driven expansion, in which patterns of accumulation could be observed shifting from productive to financial activities.3 This is particularly true for the Anglo-American economies, where key interrelationships between low interest rates, private debt, domestic demand, asset markets and consumption coalesced to produce a period of stable growth.4 The simplicity of the finance-led growth model is also its fundamental fragility: private debt generates demand that would not otherwise be there – driving up property prices and fuelling the consumer economy.5 The events leading up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis exposed the fragile balancing act of finance-led growth to manage a rapidly growing private debt stock with stagnating income flows.

This chapter focuses on the central, but often overlooked, role of the household sector in driving, sustaining and reproducing finance-led growth. A clear majority of UK households are dependent on wages and salaries for their income, which have remained stagnant and, for some, even declined in real terms in the period of finance-led growth, creating a demand for debt to plug the gap.6 Looking at both sides of the household balance sheet it becomes clear that the household sector is the feedstock of finance-led expansion by regularly remitting present-day income every month into global financial markets, either as payments into portfolio investments (mainly pensions) or as payments on debts (mortgages and other loans). By considering the claims on monthly household cash flow, we begin to catch a glimpse of the absolute limits of finance-led growth.

It is not just the role of the household sector within the macro-economic phenomenon of financialisation that is relevant to daily life, but also how sociocultural dynamics shape the ways in which the different groups within society can participate in and benefit from finance-led growth.7 Financialisation has brought with it a wider cultural shift within British society in which cultivating financial or entrepreneurial forms of citizenship is paramount for participation in the economy. The power of finance within daily life is not simply reducible to large macroeconomic structures, but mediated through cultural conversations that make finance the legitimate means through which individuals access and participate in the economy.

Financialisation Destroys the Small Savers

Falling real interest rates since the mid-1990s instigated the financialisation of households by slowly eroding the incentives to save cash in interest-bearing accounts, and pushed many households into portfolio investment vehicles in the hope of capital gains. Dwindling household savings ratios (the value of new household savings expressed as a proportion of gross household disposable income) over the past thirty years are obvious: in 1997, households saved 10 per cent of disposable income; in 2007, just before the credit crunch hit, it was 6.8 per cent, and most recently, 2017, the national household savings ratio hit an all-time low of 1.7 per cent.8 This national aggregate measure does not account for how savings habits differ based on income level and age, but nevertheless the trend is clear: in 2017, it is estimated that 9.45 million people have no savings at all, and it is believed these ‘non-savers’ are mostly young people and those at the bottom half of the income scale.9

Public policy actively supported households in their switch from cash savings to investment in appreciating asset classes, including property, in what came to be called ‘asset-based welfare’.10 This group of policies encouraged citizens to think of their asset purchases as investments which they might cash in to fuel their consumption. For example, in retirement, as the state withdrew from pension provision in times of economic difficulty; after redundancy, as the state withdrew unemployment benefits; or for education, as the state increased tuition fees. The downsides to asset-based welfare are many, chief among them being the destruction of households’ liquid savings. Since holding cash over the long term is not profitable because of (artificially) low interest rates – liquid savings, like wages, are eroded by inflation. Another important downside is that savings deposits are protected by deposit insurance and investment savings are not – meaning households hold all the risk during a market downturn. For example, in 2008, when the IceSave bank went under, large numbers of British small-saver households, enticed by interest rates of 5–8 per cent on savings deposits, were exposed to the bankruptcy of the Icelandic bank that was ultimately guaranteed by the UK Treasury. Unfortunately, those people who invested the same amount into investment savings accounts (ISAs) were not entitled to compensation.

Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis the macroeconomy has been governed by ‘unconventional monetary policy’ which has actively sought to keep interest rates artificially low (even below zero in real terms) with successive rounds of quantitative easing (QE) – this has only served to further decimate households’ savings, in the present day and in the future: first, because the banking system can no longer offer any meaningful form of low-risk, long-term cash savings; and second, because QE is driving down bond yields to such an extent that it will eventually bankrupt most pension funds. This reality points to a systemic market failure in which banks and monetary authorities cannot offer households a meaningful low-risk savings vehicle, only high-risk portfolio investments or mortgage loans. A key reason for this is that financial markets benefit hugely from the steady influx of ‘dumb money’ from the household sector because it remits income from monthly pay packets (with commensurate tax concessions) into pension/investment schemes whether markets are at a peak or a trough, and they are under a legal obligation to pay mortgages whether property prices are high or low. In the aggregate, these monthly income remittances amount to huge tides of guaranteed revenue flowing to institutional investors irrespective of firm- or market-level performance. Asset-based welfare effectively transfers all the risks of market crisis – like those experienced in the 1997 East Asian Crisis, the 2001 Dot Com Crash and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis – onto the household sector without any protections against losses, unlike the financial actors themselves who have received ever-larger bailouts in response to successive market downturns.

Homeownership Is a Highly Leveraged Investment Savings Vehicle

Perhaps the most profound way in which finance-led growth transforms everyday life is through residential housing. With savings rates falling, residential housing has become the only ‘safe’ financial investment vehicle – less volatile than portfolio investment and capable of making inflation-proof gains over the long term. Residential housing is also an engine of finance-led growth, resulting in many households becoming highly leveraged investors. Housing-based welfare is enthusiastically supported by public policies that continue to promote home-ownership as a key benchmark of economic citizenship without acknowledging its failings.11

Taking the most recent measurements from Figure 10.1, in July 2017 the total stock of debt owed by the household sector was £1.545 trillion, of which 86 per cent was debt secured or mortgage debt (£1.344 trillion). As banks developed their ‘originate-and-distribute’ business model, residential mortgages became the main way to create money and generate additional revenue for lenders, by bundling together anticipated future interest payments and reselling them multiple times across global financial markets. Residential property mortgages are a key source of new money creation in the UK economy, as banks create money when new debt deposit accounts are made and when issuing mortgages.12 More importantly, creating debt deposits secured against residential property is almost risk-free for lenders because the UK has ‘full-recourse’ mortgages, allowing the lender to not only keep all collateral but also pursue the full value of the debt from the borrower regardless of the value of the asset – a stark difference compared to the American ‘nonrecourse’ mortgage that entitles the lender only to repossess the property and sell it to recoup costs. Put simply, if the UK housing market takes a downturn all the costs are disproportionately incurred by the borrower, posing a major systemic risk to the rest of the economy.13

Figure 10.1

The everyday realities of housing-based welfare are far more complicated and differentiated than is widely assumed.14 This runs counter to popular assertions that mistakenly generalise the wealth gains from housing over the past thirty years to the next thirty years. This assumption fails to consider the present-day limits of household incomes or the existing historically unprecedented mortgage debt overhang. It is more accurate to understand wealth gains from housing as a form of intergenerational (age-based disparity) and/or regional (urban/rural or north/south) inequality. Age and place significantly shape who are the winners and the losers in the residential housing game. These factors demonstrate why housing cannot provide a generalised welfare function and why it is, arguably, wholly unsustainable over the long term.

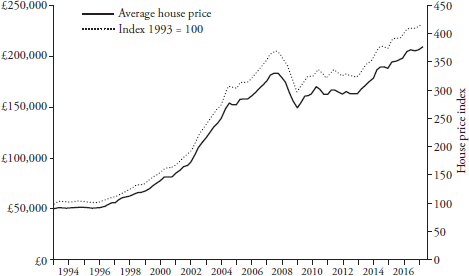

Figure 10.2 shows the UK residential house price index, the main engine of finance-led growth and an underlying justification for asset-based welfare. However, looking at Figures 10.1 and 10.2 together, both starting in 1993, it is obvious that mortgage debt and property prices rise in step. As interest rates remain low, even falling after 2008, property prices continue to increase, giving new incentives for individuals to accumulate more debt to stretch themselves in the housing market to avoid missing out on the potential return on their investment that property offers.

Figure 10.2

Credit-fuelled asset appreciation in residential housing is a driving force of finance-led growth. Mainly because it serves to bolster aggregate demand as house prices increase, homeowners can more easily remortgage their properties, releasing the equity built up in their homes to fuel additional consumption. The rapid uptake in home equity loans shows the degree to which many UK households see their house not only as a source of long-term savings (‘my house is my pension’) but also as a source of cash that serves to shore up aggregate demand. Interestingly, there is no national data collection on the stock of outstanding home equity loans (second lien mortgages). Instead the Bank of England measures ‘housing equity withdrawal’ as the change in the total stock of housing equity (not debt) as households secure lending to take out or repay debt against residential property, as well as changes in the stock of housing wealth (e.g. when new properties are built or improvements are made to existing properties but not changes in house prices).15 However, property prices are the biggest determinant of whether households withdraw equity, and there are clear downsides to converting equity into cash – namely the household’s (often only) financial asset becomes highly leveraged, transforming the overall financial security of the household sector and the wider economy. Put simply, increased uptake of home equity loans means that even those households with asset holdings – those considered more financially secure than households without any assets – are more vulnerable to income shocks, like all overleveraged investors are. The ability to use residential property as a source of cheap credit creates pronounced, yet largely unseen, inequalities between homeowners that are asset-rich and those with leveraged homes, in which the latter are vulnerable to every manner of financial market or economic shock.

Financing Daily Life with Debt

The final pillar of the financialisation of everyday life is the growth in non-mortgage (or consumer) debt in the UK over the past twenty years. From Figure 10.1, the June 2017 figures put consumer debt at an all-time high of £201.5 billion and credit card debt at £68.7 billion. That puts the average total debt per household – including mortgages – at £57,005, which is approximately 113.8 per cent of average earnings. The total interest repayments on personal debt over a twelve-month period is roughly £50.149 billion, meaning an average of £137 million per day is remitted to banks to service this debt stock.16

Understanding the unrelenting rise in consumer debt involves a more sociocultural explanation of norms around consumption, including issues like middle-class entitlements such as a university education and annual family holiday, which are increasingly funded by debt rather than forgone altogether.17 In the early days of finance-led growth, consumer debt expansion was typically understood as a direct consequence of hyper-consumerism. This is much less the case since 2008. Now it seems that many households use debt to participate in economic life.18 For example, most young people must borrow heavily to access higher education: here policy promotes private debt directly replacing public provision. In less than a decade, increases in university fees and cuts to student subsidies for higher education meant that outstanding UK student debt increased from £15 billion in 2005 to £54 billion in 2014.19 Also, many households borrow to sustain cash flow to make ends meet each month. An in-depth UK-wide study found that four factors trigger households having debt problems: a drop in income (32.5 per cent), most often from unemployment; a change in circumstances (28.5 per cent), mostly an illness in the family, an elderly parent needing care or a new baby arriving; increased outgoings (20 per cent); unexpected expenses like needing a new car or a rent increase; and overspending (15 per cent), buying high-cost consumer goods or holidays.20 Increasingly, it seems that surviving in this ‘age of austerity’ – in which falling income levels in real terms exist alongside drastic cuts to social security – means many households use debt as a safety net.

Conclusion

There is a ‘strategic silence’ in public policy understanding and response to the problems precipitated by widespread household indebtedness. Since the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the UK financial sector has enjoyed an unprecedented amount of public subsidy in the hope of shoring up confidence in this strategically important sector. However, this requires a continued reliance on debt-driven growth: the very cause of the financial crisis in the first place. Therefore, the question of what to do about indebtedness is the central economic problem that must be dealt with, particularly because current economic policy is to the detriment of the household sector. The entire economy is dependent on household debt levels continuing to grow unabated. The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) predicates its growth forecasts on ever-rising household debt-to-income levels. Most recently, in March 2017 the OBR estimated that the present-day 145 per cent of gross debt-to-income would reach 153 per cent over the following four years.21 Therefore, households are expected to absorb public spending cuts, job losses and wage stagnation at the same time as using debt to consume as if the economy was booming. This situation cannot last forever, and anyone can see that if only they care to acknowledge it.

For those people living under this debt-driven growth regime, everyday life is a vice-like grip of countervailing forces, which are experienced personally but can be refracted onto the national economy. If every household struggling with debt decided to pay down their debts the national economy would be plunged into depression, with the global economy following closely behind. However, if every household struggling with debt continues to take on more debt to maintain their standard of living, soon there will be rising insolvency rates. Currently, most households do keep up their debt repayments and regularly remit a growing portion of their present-day income to pay for all their past economic activity – creating debt-deflation pressures that are bleeding the economy by a thousand small pinpricks. However, if for whatever reason households are unable to make these regular repayments, a worse scenario will unfold in which default rates add to the portfolio of non-performing loans on banks’ balance sheets. As the 2008 financial crisis revealed, the elaborate network of financial claims flowing through the global financial system are vulnerable to default on even small-scale household-level loans (US sub-prime mortgages). Rising default rates of the household sector would, once again, start letting off sparks that could ignite another firestorm across global markets.