Sent to the Emperor from the City of Tenochtitlan on the 3rd of September 1526.

Sacred, Catholic, and Cæsarian Majesty:

Having given orders for all things concerning Cristóbal de Olid, as your Majesty was informed, I bethought me that my own person had now long been idle, attempting no new matter in your Majesty’s service by reason of my broken arm, and although not wholly recovered from it I thought it well to undertake something. Accordingly on October 12th in the year 1524 I left this city of Tenochtitlan with certain men on horseback and on foot, which were no more than those of my own household and of a few friends and relatives, together with Gonzalo de Salazar y Peralmírez, and Chirinos, factor and veedor of your Majesty. I likewise took with me the chief natives of the land, leaving the administration of justice to the Government in the hands of your Majesty’s treasurer and contador together with the licentiate Alonso de Zuazo23. In the capital itself I left great store of guns and ammunition and sufficient troops; the forts likewise were well furnished with guns and the brigs in excellent repair. The city with its alcalde was well prepared in every way for defence and even for attack if need be.

I accordingly left the capital in this order and arrived at the township of Espíritu Santo in the province of Coazacoalco, 110 leagues off. Here, while ordering certain matters within the city, I sent to the provinces of Tabasco and Xicalango informing the native rulers of my visit to these parts and bidding them to come to hold speech with me or send persons whom I could instruct as to what they were to do, the which they did, receiving my messengers very warmly and sending me seven or eight persons of lofty rank (as they were wont to do) who informed me that on the other side of Yucatán close to the coast near the Bay of Ascension there were certain Spaniards who were doing them much ill. Not only had they burnt many villages and killed certain natives, on which many had deserted their homes and fled to the woods and mountains, but they had injured merchants and traders even more severely; in such wise that all traffic with the coast which had been considerable had now ceased, and as eye-witnesses they gave me an account of practically all the townships along the coast down to where Pedro Arias de Avila, your Majesty’s Governor, is stationed: they drew the map of the whole coast on a piece of cloth from which I reckoned that I could journey the greater part of it, in particular as far as that place which they pointed out as being occupied by the Spaniards. I was glad to find such good news of a road by which I could put my plan into execution and thus bring the natives of the land to the knowledge of our Catholic Faith and the service of your Majesty, for on such a lengthy journey I was certain to pass through many and various provinces and peoples, and should be able to discover whether these Spaniards of whom I heard belonged to the expeditions which I had sent under Cristóbal de Olid, Pedro de Albarado or Francisco de las Casas. And to order all those things aright it seemed to me expedient to your Majesty’s service that I should go forward in person, especially seeing that it was inevitable but that we should discover many lands and provinces previously unknown and might succeed in pacifying many of them, as indeed afterwards happened. Whereupon, conceiving in my mind the results likely to follow from my visit, I determined, putting aside all possible toil and expense, to follow that road, as indeed I had decided upon before leaving the capital.

Before arriving at Espíritu Santo I had two or three times received letters on the way from the capital, both from those whom I had left as my lieutenants and from other persons. Your Majesty’s officials who were of my company likewise received them. I learnt that there was not that harmony between the treasurer and contador so necessary for all things pertaining to their office and the charge which I had laid upon them in your Majesty’s royal name. I did that which seemed to me best, to wit, wrote them in the strongest terms of rebuke, and even warned them that unless they made up their differences and behaved themselves very differently from that time on, I should make such provisions as would be very little pleasing to them, and would even make report of the matter to your Majesty. Later, since my arrival in Espíritu Santo further letters from them and other persons arrived, in which I learnt that their disputes still continued and indeed increased, so much so that on one occasion swords had been drawn on either side. This caused such scandal and disturbance that not only did the Spaniards arm themselves on both sides, but the natives of the city were induced to fly to arms saying that the tumult was directed against them. Seeing then that my rebukes and warnings were useless and that short of abandoning the expedition I could not return in person to put an end to the matter, I thought it good to send the factor and veedor with equal powers to those held by the treasurer and contador, to see where the fault lay and restore order. I further gave them secret powers by which if the culprits proved unamenable to reason, they should have authority to remove them from the charge which I had laid on them, and should occupy it themselves together with the licentiate Alonso de Zuazo. They should also punish the guilty persons. The matter being thus arranged the factor and veedor left and I held it as very certain that their return would produce much fruit and prove an effectual remedy to calm the passions which had been aroused; and with this my mind was somewhat set at rest.

(Cortés then set off. He had about 140 men, of whom 93 were mounted, and there were some 150 horses. He commandeered a brig which was lying in the port of the Villa del Espíritu Santo having sailed thither from Medellín with supplies for him, and sent it on to the Tabasco river with the supplies that remained, four guns and a considerable amount of ammunition. Cortés then wrote to his agent at Medellín to load two caravels and a larger ship with provisions and send them after him. He also wrote to Rodrigo de Paz bidding him send him five or six thousand pesos of gold to buy Stores. He even wrote to the treasurer at the same time asking him to lend him the money, which he did, and the ships duly arrived at the mouth of the Tabasco.

Cortés now proceeded eastwards along the coast. The land was very marshy and frequently intersected by small streams. There were also three large rivers to cross: the first two the horses managed to swim, their bridles being held by men seated in the canoes, but to cross the last it was necessary to build a bridge which was no less than 934 paces long, a thing as Cortés remarks, “very marvellous to see.” They found abundance of fruit, particularly the cocoa nut, in this province of Cupilco, as also of fish. There were some ten or twelve fair-sized towns and the natives remained quiet although somewhat overawed at the Spaniards whom they saw now almost for the first time. From the last town in the province, Anaxuxuca, Cortés sent on a few Spaniards and Indians to spy out and open up a road, and they reported many mountains and swamps ahead.

The Guaxala river lay immediately in front of them and was crossed in rafts with but a single Indian casualty. While they were doing so the boats with provisions arrived from the mouth of the Tabasco. One of the scouts had made his way up this river and reached the town of Zaguatán itself. He now sent word back by means of some of the natives. The following night in the midst of a violent rainstorm he arrived where Cortés was encamped on the further side of the river with some seventy Indians who had come with him to open up the road. On the day following the main body succeeded in reaching the town, only to find it deserted; even the seventy Indians who had assisted them had fled. For four days Cortés remained in the town thinking they would return when their fears were past, but finding they did not do so sent out parties of Spaniards who captured two native men and a few women. They could or would say nothing as to where all had disappeared, but pointed to a range of hills some ten leagues off where, they said, the chief town Chilapán was to be found on the further side of a great river, which flowed into the Zaguatán and thence into the Tabasco. They also declared that higher up the river was a town called Ocumba.

Cortés remained twenty days longer in this town. It seemed to be entirely surrounded by fearful marshes, and finally in desperation, since food was running short, a large bridge was built and the company set out in the direction of Chilapán. A smaller boat was at the same time dispatched to Ocumba. Here again the natives fled. A few men and women who were captured guided the Spaniards to Chilapán, where they arrived late the next day to find it also burnt and abandoned. Proceeding to Topetitán they found it in like state. They were already extremely short of food and found but little at Topetitán to relieve their want. The advance party was sent on to Istapán with orders to send back word as to the road, until which time the main body would remain in the city. “And so,” says Cortés, “they set off.”

But two days later having received neither letter nor any other news of them I was forced to set out also on account of lack of food, and follow them with only their track through the marshes to guide us along a terribly bad road; for I can assure your Majesty that even on the highest ground the horses sank up to the saddle girths and that although their riders were not in the saddle but leading them by the bridle. I proceeded thus for two days following the track, without news of our comrades ahead and in no little perplexity as to what I should do next; for to retrace our steps was impossible and yet I had no certainty as to what lay in front of us. It pleased God, however, Who in our greatest need is wont to succour us, that as we lay encamped greatly downcast in mind thinking that we must all perish there without hope of aid, two of my native Mexicans arrived with a letter from the Spaniards saying that they had reached Istapán. On approaching the town they found that it stood on a neck of land between two streams: the women and chattels had been already moved to the furthest bank. The men, however, remained in the town itself thinking that the Spaniards would be unable to cross the broad creek that separated them: but seeing them begin to swim it holding on to the saddle-bows of their horses, they set fire to the town and fled across the river, some in canoes and some swimming. Many were drowned in their hurry. The Spaniards arrived before the town was wholly burnt, and took seven or eight prisoners, among whom there was one who appeared to be the chieftain, intending, as they wrote, to keep them until my arrival.

It would be impossible to describe to your Majesty the joy of my men on hearing this letter, for, as I have said, they had almost given up hope. Early on the morrow we continued our march having the two Indians as guides, and late that night arrived at the town where I found all the men of the advance party in good spirits, since they had found many small maize fields, together with yucas24 and red pepper, a food commonly used in the Islands and not unpalatable. I ordered the prisoners to be brought before me and asked them by an interpreter why they burnt and fled from their own homes and villages since I had done them no harm, but on the contrary gave presents to those who received me. They replied that the ruler of Zaguatán had come through there in a canoe and frightened them greatly, persuading them to set fire to their town and abandon it. I confronted this chief with all the natives who had been taken in Zagatuán, Chilapán, and Topetitán, and in order that the natives of Istapan might see how evilly he had lied to them, I desired the others to declare whether I had done them any wrong or whether they had been well treated in my company: the which they declared, weeping and saying that they had been deceived, showing themselves truly sorry for what they had done. Accordingly, the more to reassure them I gave all of them permission to return to their homes together with certain trifles and a letter for each one of them which I ordered them to keep in their villages and show to any Spaniards who might pass that way. They would thus be secure. I bade them tell their chiefs the fault they had committed in burning and deserting their towns and to abstain from it in future, for they might remain securely at home since no hurt or damage was done them. Upon which they departed very contented, and all this being done in the presence of those of Istapán went no small way towards pacifying them also.

This business finished I spoke at greater length with what appeared to be the head man among the captives, telling him that I was come not to harm them but to instruct them in many things that it behoved them to know both for the security of their persons and goods as for the salvation of their souls. I therefore earnestly begged him to send two or three of his fellows (to whom I would add as many Mexicans) to seek out their ruler and tell him to have no fear, for I was certain that it would be greatly to his advantage to come to see me: to this he agreed and on the morrow the messengers returned and the ruler and some forty men with them. He told me that he had burnt his town and fled at the bidding of the chief of Zaguatán who had said that I should burn and slay all that I met, but that he was now aware that he had been misled. He was sorry for what was past and begged me to pardon him, promising to do all that I bade him from that time on. He also asked that certain women taken by the Spaniards on their first arrival should be restored, upon which as many as twenty were found whom I handed over to him, to his great content.

It happened that a Spaniard found a Mexican Indian of his company eating a portion of the flesh of an Indian who was killed when we took the town. He reported this to me and I ordered the Indian to be burnt in the presence of the chief of Istapán giving him to understand the reason, to wit, that he had killed an Indian and eaten him, the which was forbidden by your Majesty and had been publicly so proclaimed by me in your Majesty’s name, for which crime he was to be burnt. For I desired that they should kill no one, but rather according to your Majesty’s commands was set on aiding and defending them, both their persons and property. They should know also that it was their duty to hold and worship one true God, Who is in heaven, Creator and Maker of all things, by Whom all creatures live and are maintained, and to lay aside all those idols and heathen rites which they had hitherto held, inasmuch as they were lies and snares devised by the devil, enemy of the human race, to deceive them and bring them to eternal damnation in great and terrible torments, dividing them from the knowledge of God that they might not save themselves and partake of the glory and blessedness promised and prepared by God for those who believe in Him, the which the devil lost by his own malice and wickedness.

I was likewise come to acquaint them of your Majesty, whom divine providence has willed that the whole world should obey and serve. They also must bow under the imperial yoke and do that which we as your Majesty’s ministers should in your Majesty’s royal name command. Doing which they would be well treated and their rights both of person and of property upheld: but failing so to do they would be proceeded against and punished according to the law.

I dwelt on many other matters with which I will not trouble your Majesty as being too long. To all he agreed very readily and sent off a few of his men to bring further provisions which they did. I gave him certain trifling gifts of Spanish ware which he greatly prized and he remained with me all the time I was there.

Our road lay through Tatahintalpán: and since there was a deep river to be crossed he ordered a road to be made and a bridge built. I sent a party of Spaniards down to my ships in the Tabasco to order them to sail round the point of Yucatán and anchor in Ascension Bay where they would either meet me or receive fresh orders from me: the party was then to return bringing as many provisions as they could and following up a large creek until they met with me in the province of Acalán forty leagues off where I would wait for them. On the departure of these men I asked the ruler of Istapán to let me have three or four canoes and send in them a party of Spaniards and a native chief up-stream to allay the fears of the natives that they might not burn or desert their towns. To this he agreed very willingly, and the project bore no small fruit as I shall proceed to show your Majesty.

Istapán is a fine large town and is situated on the bank of a magnificent river. There are rich grazing grounds on either side and also good farm land. It possesses in addition a fine stretch of cultivated ground.

(After residing for a week in Istapán Cortés again set out. Owing to the winding of the river he reached the first village before the canoes and found it burnt and deserted. Thence he continued his way to Signatecpán, the next large town marked on his map. Some kind of a road had to be made through swamps and over mountains and rivers; finally after two days of stubborn labour spent in cutting a way through dense forest the guides confessed themselves lost. Cortés slaked everything on his ship’s compass, ordered leaders to press on in a straight line to the north-east and was rewarded by coming upon Signatecpán at nightfall. The town itself was burnt, but a large amount of maize had been left behind and there was good grazing for the horses. Nothing was to be seen of the advance party save a single arrow buried in the ground near the town; Cortés was greatly cast down at this, thinking that they had fought with the natives and all lost their lives. On crossing over the river, however, the whole body of natives was discovered who greeted the Spaniards quite fearlessly and confessed that they had been induced to burn their town by the chief ruler of Zaguatán, but that certain Spaniards had arrived in canoes together with natives from Istapán who had reassured them. The Spaniards had stayed two days there and then gone on up-river: Cortés immediately sent word after them, and on the evening of the following day they returned with news of success and four native canoes accompanying them. They had pacified several towns and villages and sent messengers on to three which they had been unable to reach.

Seven or eight further canoe-loads of natives arrived bearing some food and a little gold as gifts to the strangers. Cortés received them graciously, impressing on them their duty to God and to his Catholic Majesty, and some of the idols in Signatecpán were publicly destroyed.

Finally, after carefully enquiring which was the best road and getting very contrary answers, Cortés set out for the province of Acalán, leaving the natives very quiet and contented. He crossed one river with some slight loss, and pushed on for three days through thick jungle, following a very narrow path. From this he came out on to the bank of a great river over five hundred yards wide, and attempted to find a ford both above and below, but was unsuccessful. The guides told him that it was vain to look for one this side of the mountains which were a twenty days’ journey up-stream.)

I was more cast down, says Cortés, at the sight of this arm or inlet of the sea than I could possibly describe. To pass it was impossible on account of its width and the lack of canoes, but even had we had them for the men and baggage the horses would have been unable to get across; for lining either bank were great marshes and large tree roots surrounding them, so that for this and other reasons any idea of getting them across was quite impossible. Yet to attempt to retrace our steps would, it was obvious, mean the death of us all, on account of the wretched roads we had followed and the heavy falls of rain that had since taken place. For we were aware that the river in its rise must have swept away all the bridges we had made, and to build them again would be a matter of tremendous difficulty since the men were now all wearied out: in addition we bethought us that we had now eaten all the stores to be had on the road and should we return would find nothing more to eat; for I had many men and horses with me, including in addition to the Spaniards more than 3,000 native Mexicans. Yet the obstacle to our further progress remained, as I have described to your Majesty, and so formidable a one that the wit of man was powerless to remedy it, had not God, Who is the true remedy and succour of those in affliction or want, put it into my mind. I took the little canoe which the Spaniards whom I had sent on ahead had used and had the river sounded from one bank to the other, when it was found that there was an average depth of four arms’ length. I ordered lances to be tied together to examine the bottom and another two arms’ length of mud was discovered, so that the total depth amounted to six arms’ length. Accordingly as a desperate remedy I determined to make a bridge over it. I immediately ordered wood to be got to those measurements, of some nine to ten arms’ length, allowing for what would rise above the surface of the water. I ordered the Indian chieftains who had accompanied me to cut and bring wood of this length, each one according to the number of his followers. Meanwhile the Spaniards and I began to drive in the stakes, using rafts and the small canoe with two others which were found later, but to all the task seemed impossible to accomplish. Some even whispered behind my back that it would be better to turn back before all the men should be worn out and unable through weakness and hunger to do so. Indeed the murmur grew so loud among my men that they almost dared to say it to my face. Upon this, seeing them so discontented (and in truth they had reason to be since the task was truly overpowering and they had nothing now to eat but roots and herbs) I ordered them to abandon work on the bridge, saying that I would complete it with the help of the Indians. Forthwith I called all the native chieftains together and bade them consider in what plight we were, that we must either pass over or perish. I therefore begged them very earnestly to urge on their people that the bridge might be finished, and once crossed we should enter upon a great province called Acalán where there was great abundance of provisions and where we could encamp: moreover, I reminded them that in addition to the stores to be found in that land I had ordered stores to be brought up to us in canoes from the ships and that therefore in that province we should have abundance of everything; in addition to all this I promised them that when we returned to Mexico they should be very fully rewarded by me in your Majesty’s name. They promised me they would undertake the work, and began forthwith to divide it out among themselves, working at it with such skill and speed that in four days they had finished it and all the horses and men were able to pass over it. Moreover it will take more than ten years to destroy it, provided it is not interfered with by the hand of man; and even so almost the only method would be to burn it, for it contains more than a thousand stakes the smallest of which is about the thickness of a man’s body, to say nothing of smaller logs which are beyond number. And I can assure your Majesty that I think there is no man who could rightly declare after what plan or fashion the natives built this bridge; all that one can say is that it is the most extraordinary thing one has ever seen.

No sooner had the men and horses reached the other side than we came upon a great marsh full two bowshots broad and the most frightful thing that ever my men set eyes on. All the horses, riderless as they were, sank up to the saddle-cloths, nothing else appearing above the slime. To attempt to urge them on was but to make them sink the deeper, in such wise that we lost all hope of being able to get a single horse across and thought that they must all perish. Nevertheless we set to and placed bundles of grass and large branches underneath them on which they were borne up, and no longer sank, matters being thus somewhat relieved. Then as we were busy going hither and thither in our task a lane of water and slime opened up in the middle so that the horses could swim a little, by which help it pleased God that they should all escape without injury, although so fatigued and utterly worn out that they could hardly remain on their feet.

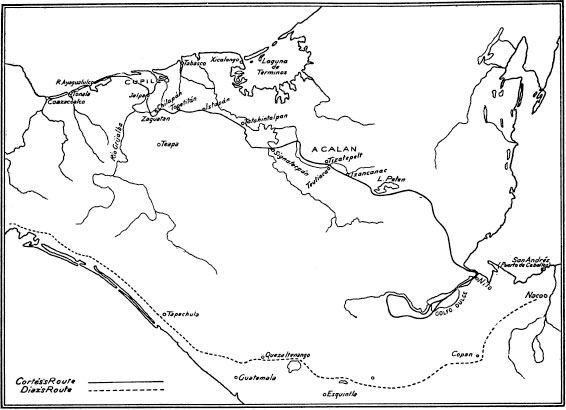

Sketch Map of Guatemala and Yucatán showing Route of Cortés from Coazacoalco to Naco.

We returned thanks to God for his great mercy towards us, and while we were so doing the Spaniards whom I had sent on to Acalán arrived with some eighty natives of that province loaded with stores of maize and birds, at which sight God knows how we rejoiced, more especially when they told us that the natives were very quiet and peaceably disposed with no desire to desert their homes. With the Indians from Acalán came two chief men from the ruler of that province, by name, Apaspalón, to say that he rejoiced greatly at my visit. Many days since he had had news of me from traders from Tabasco and Xicalango, and he was eager to meet me. He sent by their hands a little gold, which I received with as much show of delight as I could, thanking their master for the good will he showed in the service of your Majesty, and giving them a few small presents, after which I bade them return with the Spaniards whom they had accompanied, and they did so very contentedly.

They marvelled greatly at seeing the bridge we had built, and this had no slight effect on the peaceful intentions which they afterwards showed, for since their land lay among lakes and rivers they might well have thought of beating a retreat by means of them, but after seeing our handiwork they thought that nothing was impossible to us.

The same day, immediately after their departure, I set off again with all my men. We slept one night in the jungle, and on the morrow a little after noon approached the farms and plantations of Acalán. It was not long before we arrived at the prosperous town which is called Tizatepelt where we found all the natives in their houses very quiet and peaceful and great stores of food for man and beast, in such quantity indeed that it repaid us for our former want. We rested there six days, during which time a youth came to see me, of good disposition and well attended, who informed me that he was the son of the native ruler; he brought me a certain amount of gold and game, offering his kingdom and person in the service of your Majesty, and concluded by saying that his father was dead. I showed him that I was much grieved at the death of his father, though perceiving that he was lying, and gave him a collar of Flanders lace which I wore round my neck which he greatly prized. I told him that he was free to depart in peace, but he stayed a further two days with me of his own accord.

The native ruler of this town now told me that there was another town of his near at hand which could offer us better dwellings and greater store of provisions, since it was larger and had more inhabitants. He begged me to go there where I should be more comfortable. On my answering that it pleased me well he ordered the road to be opened and lodgings prepared for us. All this was duly performed and we took our way to the town which is five leagues off. We found the natives as before quiet and at home and a certain part of the town cleared for our use. This town, Teutiacá by name, is very fine, and has many magnificent temples, in two of which we lodged, throwing out the idols from their former abode; at this the people showed no great discontent for I had already spoken to them, giving them to understand the error in which they were, how that there was only one God, Creator of all things, and such other doctrines as could be briefly exposed to them, although later I did speak at greater length both to the ruler and to all his people.

I learnt from them that the larger of these two temples was dedicated to a goddess whom they held in great faith and veneration, sacrificing to her only virgin maidens of great beauty, for were they otherwise the goddess was greatly angered with them, for which reason they ever took special care to seek out such that the goddess might be satisfied, and even brought up from their earliest days those of likely appearance for this office. I likewise gave them my opinion as to what was seemly to be done in this matter with which they seemed fairly contented.

The native ruler of this town showed himself very friendly to me, entering into long conversations in which he gave me a long account of the Spaniards I was seeking and the road that I was to take. Finally he confided to me as a great secret, begging me to let no one know that he had warned me, that Apaspalón, the ruler of all that province, was alive, though he had sent to us that he was dead by the youth who was indeed his son, and was intending to turn me from my direct road in order that I should not visit his land and towns. He was warning me of this, so the chieftain confessed, because he wished me well, having received fair treatment from me. But he again begged me to keep the matter very secret for if it were known that he had warned me Apaspaóln would kill him and burn his kingdom. I thanked him much, repaying his loyalty with a few small gifts, and promised secrecy as he desired; I further promised in your Majesty’s name to reward him amply in days to come.

I lost no time in summoning to my presence the youth who had come to visit me and told him that I marvelled greatly at himself and his father wishing to deceive me, knowing as he did how much I desired to see him, to do him honour and give him certain presents as recognition of those many kindnesses which I had received in his land and which I was eager to repay. I now knew for certain that his father was alive, and earnestly requested the youth to seek him and try and bring him to me for I was certain that he would gain much by it. In answer he confessed the truth saying that he had only denied it because under orders to do so, and offered to do all he could to bring his father to me, in which he thought he would be successful, since on learning that I was not come to do any harm but actually gave presents of my own substance, he was anxious to see me, although somewhat ashamed to appear before me after his first refusal. The youth accordingly set out and on the morrow both returned whereat I welcomed them with much pleasure. The chieftain excused himself for his refusal to meet me explaining that he was afraid to do so until he knew my intentions, but once known he was glad to do so; moreover it was true that he had given orders to guide me by roads which did not touch his towns, but now he begged me to accompany him to the prosperous town where he resided, since there were more facilities there for providing me with all the necessities of life. Forthwith he had a broad road cut thither and on the morrow we set out. I ordered a horse to be given him and he rode on it very contentedly until we came to the town which is called Izancanac, very large and with many temples, standing on the bank of a great stream which runs down to the estuary of the Xicalango and Tabasco. Some of his people had left the city, the remainder were in their houses. We obtained plentiful provisions there and the ruler dwelt with me in my lodging although his own house was near by. He continued to give me detailed information about the Spaniards I was seeking and drew me a map on a piece of cloth of the road that I had to take. He also made me a present of a little gold and some women without my asking anything of him, whereas up to the present I have asked the native chieftains of these parts whether they were not willing to give me a certain amount of it. We had to pass the river and the swamp which lay on the nearer side of it. He had a bridge built, provided me with a great number of canoes, as many as were necessary, and gave me guides both for our journey and for messengers whom I wanted to send back to Mexico. Having settled these matters I presented him with a few trifles for which he had taken a liking and so leaving him very contented and all the land very quiet, I finally quitted the province on the first Sunday in Lent of the year 1525, and the whole of that day was spent in crossing the river, which was no small matter. I gave this chieftain a note at his request so that should other Spaniards come there they might know that I had passed that way, and so he remained my very good friend.

In this province an incident occurred which it is well your Majesty should know. A worthy citizen of Tenochtitlan, formerly called Mesicalcingo and now Cristóbal, came to me very secretly one night bearing a certain drawing on a paper after the fashion of their country, and gave me to understand that Guatimocin, ruler of Tenochtitlan when we captured it, and before that of Tezcuco, whom I held prisoner as a dangerous man, and afterwards brought him with me together with other native chiefs whom I thought likely to disturb the peace in Mexico, had held converse with Tetepanquencal, former ruler of Tacuba, and one Tacitecle, who had been with him in Mexico during the siege. Mesicalcingo had also been admitted to these conferences, in the course of which Guatimocin had declared that they were dispossessed of their lands and suffered under the yoke of the Spaniards, and it would be well to seek some remedy by which they might once again enjoy their ancient rights. After many such discussions it was decided that the surest remedy was to contrive the death of myself and all those who accompanied me, afterwards calling the people of these parts together and killing Cristóbal de Olid and all his company. This done they would send messengers to Tenochtitlan bidding them slay all Spaniards who had remained there, which they said would be no difficult matter since the Spaniards left there were all newly come to the land and knew nothing of war. Finally they would proclaim themselves throughout all the land so that in whatever township or village there were Spaniards they might be killed off; strong guards would be placed in the ports to see that no ship coming to these shores should ever leave them, and so no news go back to Castile. In this way they would be rulers as they had been before. They had already divided out the land amongst them and had allotted one province to Mesicalcingo.

I gave thanks to God that I had been warned of his treachery and as soon as dawn came arrested all the chieftains concerned, placing them in separate confinement. I then questioned them about the matter telling each one that the others had confessed, since they were unable to communicate one with another. On this they all admitted that Guatimocin and Tetepanquencal had been prime movers in the affair and that while it was true that they had listened to them yet they had not consented to the matter. Accordingly the two leaders were hanged and the others freed, their guilt apparently amounting to no more than that of listening, although that in itself was worthy of death. Nevertheless the judgment was left open so that if at any time they attempted any such treachery they might be severely punished. Yet I think they are unlikely to attempt it for they have never found out how I learnt of the plot and think that I must have done so by some magical means. They consequently believe that nothing can be hidden from me. For they have often seen me draw out a mariner’s chart and compass in order to ascertain the way, particularly when we are near water, and believed, as they confessed to many of my men and even on occasion to myself, that I made use of these instruments to find out whether they were faithful to me, and have often desired me to look into the mirror and at the map, saying that I should see there that they were faithful, since there was nothing I did not know by means of that instrument: I gave them to understand that this was true.

This province of Acalán is indeed of great size, containing many people and towns, a large number of which were visited by the Spaniards of my company. It is likewise abounding in food of all kinds, especially in honey. Many traders and natives carry their merchandise to every part, and they are rich in slaves and such articles as are commonly sold in the country. The province is completely surrounded by streams, all of which run into the Bay or Harbour of Endings (Términos) as they call it; from here they carry on a great trade by means of canoes with those of Xicalango and Tabasco, and even it is thought, although not known entirely for certain, that they cross in their canoes to the other Southern Sea, so that this land of Yucatán would prove to be an island. I shall endeavour to discover the secret of this and will send your Majesty a true account of it. I could not find that there was any other chieftain in the province except this Apaspalón, whom I have already mentioned to your Majesty, and who is the biggest trader and owner of sea-going ships.

And the manner of his acquiring such wealth and trade I observed in the town of Nito, where as I shall describe to your Majesty I found certain Spaniards of the company of Gil González de Avila; for even there, there was one quarter of the town peopled by his agents, among whom was his own brother, who sold such goods of his as are most common in these parts, to wit, cocoa, cotton cloths, colours for dyeing, another sort of paint which they use to protect their bodies against the heat and the cold, candlewood for lighting, pine resin for burning before their idols, slaves, and strings of coloured shells, which they prize greatly for the adornment of their persons. At their feasts and merrymakings a certain amount of gold changes hands, but of poor quality containing an admixture of copper and other metals.

To Apaspalón and the other chief men of the provinces who came to see me I spoke just as I had done to all others whom I had met with in my march concerning their idols, and what they must do and believe to be saved, as also that which they were obliged to do in the service of your Majesty. In both these matters they seemed well pleased, and burnt many of their idols in my presence, saying that thenceforward they would honour them no more and promising ever to obey whatever was commanded them in your Majesty’s name. I thus took my leave of them and set out as I have already described.

(Four Spaniards had been sent on ahead with a couple of native guides to spy out the road, and the main body were ordered to carry each man provisions sufficient for a six days’ march. The scouts returned saying that the road was good and that they had actually reached some outlying farms of the province, where they had seen a few natives without themselves being perceived. Further scouts were immediately posted a league in advance of the vanguard opening up the road in order to capture any stray natives whom they might come across and so prevent the alarm being given. Two traders of Acalán were thus caught and consented to accompany the Spaniards as guides. The whole body slept that night in the jungle. The next day four Mazatcan Indians were discovered armed with bows and arrows, seemingly on the watch, of whom only one was captured owing to the denseness of the forest. The others accordingly waited until the Spaniards were past and then attacked their Indian followers but were soon beaten of. In order to avoid delay Cortés now pushed on with a small body hoping to reach the town before nightfall, but was held up by a bad swamp and had to wait till morning to bridge it with boughs. The night was spent in a tiny hut. Riding forward on the morrow they came to the town three leagues on the further side of the marsh. It was high and strongly fortified so that they rode round it for some time seeking an entrance. Finally, on forcing their way in they found it deserted but well stocked with provisions. The fortifications were more than usually elaborate and included the natural ones of a lake and torrent flowing into it and also, within, a deep ditch, a wooden breast-work, and lastly a circular Stone wall some twelve feet high. The neighbouring town of Tiac was likewise taken and messengers sent forth to the natives who began to come in, bringing gifts of food and clothing. The chiefs, however, remained obdurate, and Cortés dismissing the Acalán traders to their own homes proceeded on his way eastward.)

Leaving the province of Mazatcan I followed the road to Taica, sleeping in the open after marching four leagues. The road ran through entirely deserted country, traversing great mountain lands in one of which there was a dreadful pass named by us the Alabaster Pass, on account of the rocks and peaks being all made of that material, very fine. On the fifth day the outriders ahead came upon a huge lake, seemingly an arm of the sea, and such I believe it is on account of its size and depth, although its water is sweet. They perceived a town on the island in the middle of it which the guide assured them to be the biggest in the whole province of Taica, but without canoes it was impossible to cross over to it. On this, the Spaniards who were riding ahead being uncertain what to do sent back one of their number to acquaint me with what was happening. I halted all my troops and went forward on foot to examine the shape and position of the lake. On coming up with the advance guard I found that they had captured one of the inhabitants of the town as he was coming armed in a tiny canoe to spy out the road and see if there were any strangers abroad: and although he was not on his guard he would yet have escaped my men had it not been for a dog which they had there, and which got hold of him before he could throw himself into the water. I questioned this Indian and he told me that nothing was known of my coming. On my asking whether there was any passage to the town he replied no, but that nearby on the further side of a small stream leading from the lake there were certain farms and houses where, he thought, we could procure some canoes, if we arrived there without being perceived. I immediately gave orders that the main body was to follow after me and went forward with ten or a dozen bowmen on foot whither the Indian guided us. We waded through a long stretch of marsh and water, such as would have come up to a horse’s girth and sometimes higher, and finally arrived at some farms, but what with the badness of the road and the fact that for a great part of the time we could make no effort to conceal ourselves, it was impossible to remain unseen, and at the moment when we arrived the people were already putting off in canoes and making for open water.

I quickly pressed on along the bank for two-thirds of a league through the farmland, but everywhere we had been perceived and the natives were already fleeing. It was now late, and though I still continued the pursuit it was in vain.

I camped in the farms nearby assembling all my men and allotting them sleeping quarters with all the care I could, since the Mazatcan guide informed me that this was a very numerous and warlike people. He declared himself willing to go to the town on the island something over two leagues distant, in the little canoe in which the native had come. He would speak to the chief, Canee by name, whom he knew very well, and would tell him my intentions and the reason of my coming to these lands which he himself knew and had seen having come with me thus far; and he believed that the chief would be reassured by this and would give credence to what he said, for he was very well known to him and had stayed many times in his house. I forthwith handed over to him the canoe and the Indian who had come in it thanking him for his offer and promising him that if he succeeded in his mission he should be very amply rewarded. He accordingly went off and was back at about midnight with two chief men from the town who declared that they were sent by their lord to see me and assure themselves as to what my messenger had said that they might know what I desired. I received them kindly making them certain trifling presents and told them that I was come to these lands at your Majesty’s command to explore them and convey to the rulers and peoples of it certain things behoving to your royal Majesty’s will and service. I bade them tell their chief that putting aside all fear he should come where I was, and that meanwhile for greater security I was willing to give them a Spaniard to go with them and remain as a hostage until their chief should return. Upon this they went off, and the guide and one of my men with them. Early on the morrow the chief arrived with some thirty warriors in five or six canoes and with him the Spaniard whom I had sent as a hostage. He appeared very pleased to come and for my part I received him very warmly. It was the hour of mass when he arrived and I accordingly had it sung before him with great solemnity, the players on the flageolets and the sackbuts whom I had with me assisting. He listened to these with great attention and regarded the ceremony with equal wonder. Mass finished, the friars who accompanied us approached and made him a sermon by means of the interpreter, in such fashion that he was well able to understand the mysteries of our faith, for they explained with many reasons how that there was only one God, and discovered to him the error of his own religion. He plainly showed and said that he was well content and declared himself eager to destroy his idols straightway and believe in that God of Whom we told him, for he wished greatly to know in what way he must serve and honour Him. If I would visit his town, he said, I should see him burn the idols in my presence, and he desired me to leave there in his town such a cross as he was told I had left in all the other towns through which I had passed.

After this sermon I again had speech with him, telling him of the greatness of your Majesty, and how both he and all of us in the world were your Majesty’s subjects and vassals and obliged to do him service in return for which your Majesty would grant great favours to those who so obeyed, such as I had already granted in your Majesty’s name to all in these parts who had offered themselves in his service and placed themselves under the royal yoke, and so I promised to him also.

He told me in reply that until then he had recognized no one as his rightful lord nor had known anyone who should be so. It was true that some five or six years since certain Indians from Tabasco had told him of a captain who had passed that way with a company of our nation, and after beating them three times in battle, had told them that they must become vassals of a great ruler, and all else which I now declared to him; was the matter, he asked, all of a piece? I replied that the captain of whom the Tabasco Indians had informed him was none other than myself, which he might verify by speaking with the interpreter, Marina, who has ever accompanied me, for it was in Tabasco that I had been given her together with twenty other native women. She accordingly spoke with him and assured him of the truth of what I said, telling him how I had won Mexico and describing all the lands which I held subject under the imperial yoke of your Majesty. He showed himself delighted to hear this and declared himself very willing to become the vassal of your Majesty, saying that he should be happy to serve so great a lord as I described your Majesty to be. Upon this he ordered birds, honey, a little gold and a few strings of coloured shells which they greatly value to be brought and presented them to me. I also gave him certain trifles which I had with me with which he was very well pleased. He had dinner with me with great content and after dinner I told him that I was seeking certain Spaniards on the sea-coast, for they were of my company and I had sent them thither but had had no news of them for many days. I begged him to tell me anything that he knew of them. He replied that he had much information about them, for quite close to them were certain of his vassals who provided him with supplies of peanuts with which the land abounded, and from these and other traders who were constantly travelling backwards and forwards he often received news of them. He offered to give me a guide to where they were, but warned me that the road was very rough and lay over many steep and rocky mountain lands. It would be far less fatiguing if I were to travel by sea.

To this I bade him consider that for so large a company as that which followed me together with our baggage and horses it was impossible to provide sufficient ships and we were therefore forced to go by land. I begged him to show me a way to cross the lake, and he advised me to proceed up the shore some three leagues to a point where there was dry ground, when again proceeding my men could take the road opposite his town. Meanwhile he begged me very earnestly while the troops were making this detour to go with him in a canoe to visit his town and house where I should see him burn the idols and could have a cross made for him. Accordingly, in order to please him, though against the wishes of my men, I got into one of the canoes with about twenty men, mostly bowmen, and crossed to his town where we spent all the day in festival. At nightfall I took my leave of him, embarked again in a canoe with a guide whom he gave me and crossed to the other side to sleep on land, where I found already many of my men who had circled the lake, and so we passed that night together. I left in this town or rather on a farm a horse which had run a sharp stake into its leg and could not walk. The chief promised to take care of it for me, but I know not what he will make of it.

On the morrow, assembling my men I set off following the path pointed out by the guides. After about half a league we came to a stretch of flat pasture land which was succeeded by another rocky portion some league and a half in length which again changed to a very fine open plain. I here sent on a few horse and foot a very long way ahead to take prisoner any natives that they met with on the plain for I was informed by the guides that we should come up to a town before nightfall. In this place we found many fallow deer of which we killed eighteen on horseback with our lances. But what with the sun and the fact that the horses had not run for many days (since we had been travelling through nothing but mountainous country) two of them died and many more were in great danger of doing so.

Our hunting done, we pursued our way and soon came up with some of the outriders who had stopped, with four Indian huntsmen whom they had caught, together with a dead lion and some iguanas, a kind of large lizard which are to be found also in the Islands. I enquired of these persons whether news of me had reached their town. They replied no, and pointed it out to me, which seemed to be not more than a league away on the side of a hill. I made all haste to arrive there thinking to find no hindrance in the way, but as I was about to enter the town and saw my men already making towards it, I suddenly perceived a very deep stream lying right in our way. Upon this I halted and shouted out to the natives. Two of them approached in a canoe bringing about a dozen chickens and game quite near to where I had stopped with the water up to the saddle-girths of my horse. They then stopped and would come no further, and although I stayed there a long time talking and attempting to reassure them they refused to approach any closer, and finally began to paddle back towards the town in their canoe. Upon this a Spaniard who was on horseback near me leapt off his horse into the water and swam towards them. Frightened, they abandoned the canoe and other foot soldiers who were able to swim came quickly up and captured them. By this time all the natives whom we had seen in the town had disappeared and I demanded of the captives where it was possible to cross, upon which they showed me a road leading to a place about a league up-stream where there was dry ground. We reached the town that night and slept in it having marched eight good leagues that day. The town is called Thecon and its ruler Amohan. I remained here four days getting together provisions sufficient for six, which was the time, so the guides told me, it would take to cross the desert. I was also hoping that the ruler of the town would come in, having sent a reassuring message to him by the hand of the Indians we had captured, but neither he nor they ventured to show themselves. Having gathered together all the stores that could be found there I again set out, travelling the first day through very good country, level and fertile, with no mountains and but few stones. After six leagues we came upon a great house standing at the foot of some hills and hard by a river with two or three smaller ones close to it, and surrounded by tilled land. The guides informed me that the house belonged to Amohan, ruler of Thecon, and was kept by him there as an inn, since great numbers of traders were accustomed to pass that way.

I stopped there the whole of the day following our arrival. It was a feast day and the delay gave the men who were going ahead time to open up the road. We had some excellent fishing in the river, catching a large number of shad without losing so much as a single one out of the nets. On the morrow we again set off along a bad road leading over hills and through wooded country for close on seventeen leagues when we came out on to the plains again bare save for a few pines. The plain lasted two leagues in which space we killed seven deer, which we ate in the valley of a delightfully fresh stream which we came upon at the further side of the plain. We now began to ascend a pass, short but so rough that the horses though led by the bridle could only climb it with difficulty. About half a league of downhill easy going succeeded this and then we began to climb another hill, measuring almost a league and a half up to its summit and an equal distance in descent, and all over such rough and stony ground that there was not a single horse which did not lose a shoe. I slept that night in a dried-up river bed and remained there almost till vespers of the next day waiting for the horses to be shod, yet although there were two blacksmiths and more than ten soldiers assisting them, they could not finish shoeing all through that day. I accordingly went forward some three leagues to pass the night leaving many of my men behind both to shoe the horses and to wait for the baggage which on account of the bad roads and the great rains had not been able to keep up with us.

I again set out on the morrow, the guides telling me that nearby there was a village called Asuncapín belonging to the ruler of Taica, and that we should reach it in good time to camp there for the night. After four or five leagues we arrived at the village and found no natives there. I remained in camp there two days to wait for the baggage to come up and to gather together provisions, after which we resumed our road passing through Taxuytel five leagues further on where we slept the night and found great abundance of peanuts but only a meagre quantity of maize and that green.

The guides and the head man of the village here informed me that we should have to pass a very high and rocky range entirely devoid of habitation before arriving at the next village, known as Tenciz, belonging to Canee, chief of Taica. We did not stay long here but set out the very next day, and after seven leagues of flat began to climb a pass which was in truth one of the marvels of the world—I mean the roughness and cragginess of the pass and surrounding hills, in such wise that one is powerless to describe it in words, nor would anyone hearing them be able to form any true idea, only your Majesty must know that we took no less than twelve days in getting through the pass which was eight leagues long. It was on the twelfth day that the last of my men passed through, and of the horses which accompanied them seventy-eight died either through falling down precipitous slopes or breaking their legs: all the rest were so crippled and broken that we thought that not a single one would be fit for use again, and indeed those that escaped were more than three months before they really recovered. During all the time that we were filing through the pass rain never ceased night or day. The rocks were such that no water remained on the surface for drinking and we thus suffered greatly from thirst. Most of the horses died on account of this, and had we not collected water in pots and vessels which were hung outside the rough huts we erected each night, and which owing to the tremendous rainfall provided some for ourselves and our horses, not a single man or horse would ever have escaped from those mountains.

On the road a nephew of mine fell and broke his leg in three or four places, which increased not only his burden but that of all, for to carry him across those mountains was no light matter. To put an end to our ills we found a league before Tenciz a great river so swollen and torrential with the rains that it was impossible to pass: but the Spaniards who were going on ahead had gone up-stream and found a way of passing, which is, I think, the most marvellous that has yet been heard or even thought of. The river winds at this point some two-thirds of a league out of its course by reason of two great mountain peaks which stand right in its way. Between these peaks there are ravines through which the river rushes in the most terrifying and impetuous manner, and of these there are so many that the river can only be crossed between the two peaks. Accordingly we cut down great trees and threw them across from one side to the other, and so passed over in no little peril, clutching hold of a rope of thin reeds which was also fastened from one side to the other: but anyone who had lost his balance in the slightest and had fallen would have met with certain death. There were over twenty of these ravines to be passed before the whole river was crossed, and the business took two days. The horses swam across lower down where the current was less swift, and many of them took three days after that to reach Tenciz, which was not, as I have said, over a league away, but they were so broken by crossing the mountains that they had to be practically carried, being unable to walk.

I arrived at this village of Tenciz on the Saturday before Easter. Many of my men who had horses arrived three days later, but the Spaniards composing the vanguard had arrived two days before, and finding natives in three or four of the dwellings had taken some twenty of them prisoner, for they were quite unprepared for my arrival. I enquired of these whether there were any provisions to be had, to which they replied that there were none either there nor anywhere in their land. This put us in yet greater need than in what we were already, for during the last eighteen days we had eaten nothing but the shoots and nuts of cocoanut palms, and but meagrely of these since we had not the force to cut them. The headman of the village told me, however, that a day’s journey up the other bank of the river there was a large town in the province of Tahuycal and that there we should find great store of maize, cocoa and chickens. He offered to provide me a guide thither, and I immediately dispatched an officer with thirty foot and more than a thousand of our Indian allies, in which venture it pleased our Lord that they should find great abundance of maize, and the land itself deserted of people. We thus secured some provisions although on account of the distance only with much labour.

I sent forward at this time certain Spanish bowmen with a native guide to explore the road which we had to take towards Acuculín. They reached a village some ten leagues further on and six from the chief town of the province which goes by the same name (its ruler being one Acahuilguín). Being unperceived, they captured seven men and a woman in one house and returned with them, to report that the road so far as they had followed it was somewhat difficult but light in comparison with what we had already passed. I questioned the Indian captives as to the Christians whom I was seeking, in particular one native of Acalán, who informed me that he was a trader and had his warehouse in the town of Nito where the Spaniards whom I sought were residing, and where a large amount of trade was carried on between merchants from all parts. The traders of Acalán had their own especial quarters in this town among whom was a brother of Apaspalón, the ruler of Acalán. The Christians, he proceeded to relate, had attacked them by night, taken the town and robbed them of the merchandise stored in it, which was in no small quantity. Since then, which was perhaps as much as a year ago, all the former traders had made their way to other provinces; he and certain other merchants of Acalán had obtained permission from Acahuilguín to settle in his territory, and had built a little town in a place which he had assigned to them. There they carried on their trade, diminished though it was since the coming of the Spaniards, for the easiest passage lay through Nito and they no longer dared to take it. He offered, however, to guide me to where they were, but warned me that we should have to cross at no great distance a huge arm of the sea, together with mountain ranges both many and steep, some ten days’ journey in all. I rejoiced greatly at finding so excellent a guide and did him much honour. The guides whom I had taken with me from Mazatcán and Taica spoke with him, saying how well they had been treated by me, and on what friendly terms I was with Apaspalón, their lord. At this he appeared somewhat reassured, and so trusting to this I ordered him to be unbound together with those who were captured with him. Moreover, I so far placed my confidence in him as to send back the guides I had brought with me, giving them a few trifling presents for themselves and their rulers, and thanking them for their pains, with all which they departed very contented. I then immediately sent on four of the natives of Acuculín and two from Tenciz to speak with Acahuilguín and reassure him so that he should not attempt to flee. After them came those who were entrusted with the business of opening the road. I myself set out two days later owing to shortage of provisions, although we had need enough of rest, especially so far as the horses were concerned. However, leading them for the most part by the bridle we set out, and when dawn of the next day appeared it was to find that both the guide and the other natives of Acuculín had disappeared, at which God knows what grief I felt, especially in that I had sent the other guides back to their homes.

I continued my way, camping that night in the woods five leagues further on and traversing that day mountain passes of no small difficulty, in one of which indeed a horse broke down completely which up till then had been sound. The following day we marched six leagues and crossed two rivers, the first by a tree which had fallen across it from one side to the other, the men crossing by this means and the horses by swimming, two mares being drowned; the second we crossed in canoes, the horses again swimming, and we then camped at a little settlement formed of as many as fifteen newly-made huts. I learned that these had been built by the Acalán traders who had abandoned Nito, the town of which the Spanish settlers had taken possession. I remained there a whole day waiting for my men and the baggage to come up, and accordingly sent ahead two companies of horse and foot to the town of Acuculín. They wrote to me, saying that they had found the town deserted, save for two men in a great house belonging to the ruler, who, so they declared, had been ordered to remain there until my arrival in order to acquaint their lord of it, since he had already heard of my approach and would rejoice greatly to see me. He himself would come immediately on hearing that I had arrived; accordingly one of the two had gone off to inform their ruler and bring back certain provisions while the other had remained behind. They had found cocoa-nuts on the trees, but no maize: the pasturing for the horses, however, was fairly good. On arriving at the town I enquired whether the chieftain had arrived or his messenger returned, to which they replied no, and I accordingly questioned the one native remaining as to why he did not come. He did not know and was himself expecting his arrival, but it might be that he had waited to know that I had definitely arrived.

I waited two days and then spoke to him again; he still could give me no reason for the delay, but asked me to send some Spaniards with him, since he knew where their chieftain was and would tell him. He was straightway sent off with ten Spaniards and led them some five leagues through the jungle to some huts which they found deserted, but which according to the Spaniards certainly seemed to have been lately occupied. The same night their guide gave them the slip and they returned. I thus remained entirely without a guide, which in itself was enough to double our difficulties, and accordingly sent out bands both of Indians and Spaniards who patrolled the whole of the province for more than a week without so much as catching sight of a native, save for a few women who were little to our purpose, for they neither knew the road nor could they give any news of the chieftain or the people of the province. One of them told us that she knew of a town two days’ journey thence, called Chianteca, where there were people who would give us news of the Spaniards whom we sought, since there were many merchants and persons there who held commerce in diverse parts. Accordingly I sent some of my men with this woman as guide, and although the town was two good days’ march from where I was and the road uneven and deserted, yet the natives got wind of my coming and no one was captured.

We had now practically lost all hope in that we were without a guide, and were unable to use the compass on account of the mountain ranges encircling us which were the roughest and steepest ever seen, without so much as a road leading out of them in any direction other than that by which we had entered. At this moment, however, it pleased our Lord, that we should find in the jungle a boy of about fifteen years, who on being questioned replied that he would guide us to some farms in Teniha, another province which, I remembered, we had to pass through. These, he said, were two days off, and accordingly we set out, and in two days’ time arrived at the farms where the advance guard captured an old man, who in turn guided us to the town of Teniha, another two days’ march further on.

Here four more Indians were captured who Straightway gave me very definite news of the Spaniards we sought, saying that they had seen them and that they were but two days’ journey off in the town whose name I had already heard, Nito, which as being the centre of much merchandise was well known in those parts. Indeed, I had already had reports of it in the province of Acalán, as I mentioned to your Majesty, and now two women, natives of Nito, were actually brought before me. From these I received a more detailed report, for they informed me that they had been in Nito when it was captured by the Spaniards, who had attacked it by night and so taken prisoner both themselves and many more, following which they had served certain of the Spaniards as slaves, the names of whom they now recounted to me.

I cannot express to your Majesty the gladness which I and those of my company received from this news which the natives of Taniha gave us, to find ourselves so near the end of so arduous a journey. For even during the four days’ march from Acuculín we met with innumerable difficulties. There were no roads and our way lay through rough and precipitous mountain paths from which several of the horses slipped and were killed. A cousin of mine, Juan de Avalos, rolled with his horse down one sleep slope, broke an arm, and, had it not been for the breastplate he was wearing which saved him from the stones, would have been dashed to pieces; as it was he was only rescued with great difficulty. We suffered many other trials too long to recount and especially that of hunger, for while we Still had a few pigs left from those which we had brought with us from Mexico, yet for more than a week before arriving at Taniha we had not tasted bread, and had eaten only cocoanuts cooked with the meat, without salt, which had long run out, and a few kernels. And even on coming to these villages we found there nothing to eat, for being so near the Spaniards the natives had long ago deserted them through fear of being attacked, although from what I afterwards found out from the state of the Spaniards they were perfectly safe. Nevertheless the news that we were so near our destination made us forget all our sufferings of the past and enheartened us to bear those of the present which were no less acute, especially that of hunger, which was indeed worse for we even ran short of cocoa-nuts, which could be cut only with great difficulty from exceptionally large and lofty palms, the work of cutting a single one taking two men a whole day and the fruit being then consumed in half an hour.

The Indians who brought me the news told me that there were two days of bad road ahead and that then we should come upon a great river flowing between us and Nito which could only be crossed by canoes since it was too wide to swim. I immediately dispatched fifteen of my men on foot to go with the guides, examine the road and the river, and try without raising an alarm to capture one of the Spaniards in order to find out what company they were, whether of those whom I had sent with Cristóbal de Olid or Francisco de las Casas or of Gil González de Avila. They accordingly reached the river, took a canoe from some native traders and there remained hidden for two days, at the end of which time a canoe put off from the other bank of the river where the Spaniards were with four men in it fishing. These they captured without being perceived from the town, and returned with them to me. I learnt that the inhabitants of the town were of the company of Gil González de Avila, all weak and almost dying of hunger. On this I sent two of my servants back to the town in the canoe with a letter acquainting them of my arrival, telling them that I intended to cross the river, and begging them to come with all boats and canoes that they had to this end. I then set out with all my company for the river where we arrived after three days’ journey. There I met a certain Diego Nieto who informed me that he was there to represent the chief justice. A boat and canoe were brought in which I and some ten or twelve others passed over to the town, though not without some considerable difficulty, for a wind caught us in the crossing which is very wide there (being near the mouth of the river), and we were all in grave danger of being drowned: however it pleased God to bring us to the harbour. On the morrow I procured other boats which were there and bound the canoes together two and two, in which manner the whole company, men and horses, passed over during the next five or six days.

The Spaniards whom I found there numbered some seventy men and twenty women, whom Captain Gil González de Avila had abandoned. They were in such a strait that it was the most sorrowful sight in the world to see them and the joy with which they greeted my arrival, for in truth if I had not come not one of them could possibly have escaped alive. For in addition to being few in numbers and without arms or horses, they were ill, wounded and half-dead with hunger, the provisions they brought from the Islands being all finished together with such as they had found in the village when they captured it from the natives. And once finished they had no means of securing more, for they were not in a condition to forage for provisions in the land and even if such had been brought from the Islands they were settled in a part which had no way open to the coast, or at any rate they had been totally unable to find one, and indeed such a road was only found with great difficulty afterwards. They had therefore never ventured more than half a league from the village in which they were settled. Seeing, then, the great necessity of these people, I determined to seek some means of providing for them until I could send them back to the Islands, whither they were preparing to go. For out of their whole company there were not eight fit to remain as settlers. I immediately sent out some of my men in the two ships which were there and in five or six smaller Indian boats to go in various directions. The first expedition I directed to the mouth of the river Yasa, ten leagues from this town and in the direction from which I had come, for I had been informed that there were villages there and plentiful supplies. A party penetrated some six leagues up this river where they came upon some large cultivated farms, but the natives perceiving their coming moved all stores into some large barns hard by and betook themselves with their wives, their children and their belongings into the mountains. Just as the Spaniards were approaching the barns, so it was reported to me, a tremendous storm of rain came on, upon which they took shelter in a large building, and thoughtlessly, being soaked to the skin, they laid aside their arms and even removed their armour and clothes, to dry them and warm themselves in front of fires which they had made there. Suddenly they were attacked by the natives and many taken unawares were wounded, in such wise that they were forced to re-embark and return to where I was, without more provisions than those which they had taken hastily as they departed. God knows how grieved I was not only to see them wounded and some dangerously so, but also on account of the encouragement this success would give the Indians, and finally at the small succour they brought us for the great need in which we were.