‘Maybe if we broke it up.’

‘Couldn’t you pouch it, Furball?’

‘I did pouch some of it.’

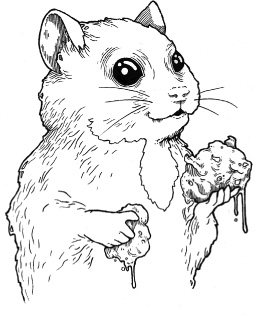

Furball felt too shy to admit that the bit of seed sandwich in her pouch had tasted so delicious that she had quietly de-pouched and eaten most of it.

She and the two mokes were hiding under the dresser. They had managed to drag most of the sandwich across the floor. From where they crouched, they could see the Converse of the Giant’s mum moving about the room. They heard angry noises as she swept up the crumbs from under the table.

Buster said, ‘Reckon vats floor-flood what she’s puttin’ vere.’

Nobby and Furball had been concentrating on how to get the various pieces of honey-coated seed through the gap at the top of the skirting board. They had paid much attention to the Giant’s mum.

‘Remember ole Uncle Barney?’ Buster said.

‘Buster,’ said Nobby. ‘We’re trying to take food to Mum.’

‘Up the duff,’ suggested Furball, without knowing what she meant. The two mokes ignored this.

‘And all you can do is talk bout Uncle Barney and the flippin floor-food.’

‘Wanna watch wot you eat off floor,’ said Buster.

‘Yeah. Well.’ Nobby agreed.

‘See vat tray vere…’

Buster was so persistent that for a moment the others abandoned the sandwich problem and came to the edge of the dresser, to the part of the floor in daylight. Not far away, in the corner of the dresser nearest the kitchen window, was a small yellow tray – large enough, say, for four hamsters to stand together on it, side by side. It had a springy-looking yellow surface, a bit like a carpet. Furball thought it looked a comfortable sort of thing, something a hamster could play on.

‘Vat tray,’ said Buster. ‘See it.’

Nobby admitted he could see it.

‘She put vat tray darn,’ said Buster. ‘Now, the other one, the one wot Furball calls Giant –’

‘The Giant,’ agreed Furball. ‘She’s very nice. I’m sure she would feed us all if she could. That’s why I’ve had this idea that we could all live together, in the shed outside Lundine…’

But Buster wasn’t listening. If he had listened, he wouldn’t have believed it for a moment. As if any oom, even the Giant, would offer food and shelter to all the Lundine mokes – that wasn’t what ooms did.

‘The Giant,’ Buster continued. ‘Now the Giant, I grantcha. She might – I’m only saying might mind – might put darn food which weren’t floor-food. No stuff. No stuff wot Uncle Barney et, know whaddeye mean. Safe food. But Ole Converse. Old Gym-shoes…’

‘Giant’s mum,’ said Furball. She felt suddenly that she missed the Giant. Standing there in the half-shadows under the dresser, and hearing Buster talk in tense, excited tones about the dangers of being at large, she thought how much she’d like to be held in the Giant’s gentle hands, to run up her jumper, down her sleeve, and to poke out her pink nose and wiggle her whiskers while all the ooms exclaimed, ‘Chum! Chum!’

‘Ole Gym-shoes put food darn for mokes?’ Buster was saying. ‘Don’t make me larf. Nar. Vat tray. I’m not saying it’s floor-food exactly. Not as such. But vere’s sommat not right. Know whaddeye mean?’

Furball didn’t know what Buster meant. The tray-carpet (or trampoline perhaps?) looked like a toy which the Giant’s mum had kindly placed on the floor. It seemed quite harmless to Furball.

Nobby, who stood beside her, had become tense. He clenched and unclenched his paws.

‘Mebbe Buster’s right nall.’

‘I do not think,’ said Furball coldly, ‘that the Giant’s mum would do anything to harm me.’

‘Mebbe not you, Furba – but mokes. Mokes is different. She’d do summat to arm mokes. Never forget Uncle Barney. Now e et floor-flood. Not sayin it were put darn by Giant-mum. But by an oom. And e copped it.’

‘Not forgettin Aunty Flo in the snapper,’ said Buster.

‘Splat she went,’ said Nobby.

‘I’m sure you’re wrong,’ said Furball. ‘Anyway, I never met your Uncle Barney and your Aunty Flo. They’re only stories.’

‘Yeah,’ said Nobby. ‘Only stories – like Ole Murph what the ooms put in ole, filled it with mud. Only stories. Only see it wiv me own eyes.’

There was silence as the three of them stared at the little tray. Furball knew she was right. She knew the Giant’s mum would never, ever do anything to harm her. She was on the point of proving the mokes wrong, showing them the new tray was harmless, possibly even a toy, by running out and playing on it, when Buster said, ‘Anyway, Furball ole girl, ow bart the grub ven?’

‘Grub.’

‘Give sandwich ole eave-oh.’

After several unsuccessful attempts to squeeze the largest piece of sandwich through the slit at the top of the skirting board, they decided to break it up into small pieces. This was easy for Furball since she was much larger and a better climber than the mokes. Then she pouched what she could, climbed the skirting board once more, and with much squeezing and pushing and puffing and panting, managed to drop herself down in the grey dark dust on the other side.

‘Mum’s garn deepest Lundine,’ Nobby said, leading the way.

(Kitty’s mum had been right – there was a passage under the kitchen floor which led from the dresser to the bottom of the stairs.)

Furball was good at burrowing and she was used to darkness, but she didn’t like the tunnel. It was dirty and dusty and smelly. It was horrid. So she was surprised when Nobby put down his bit of sandwich and exclaimed, ‘Good old Lundine!’

Buster, too, paused for breath and agreed. ‘You feel safe in here.’

Furball wondered if they were taking her up the duff, where they’d said Mokey Moke had gone – because she was ‘spectin’. But every time she talked about it with them, the mokes had squeaked with such wild laughter that she was too shy to say any more. She didn’t know what they meant or what was going on in Mokey Moke’s life, and this made her feel foolish. So she said nothing while the two mokes enjoyed the warm, choking, dusty air. And when they skipped onwards, she followed.

They scuttled and jumped and ran in short darts for what seemed a long time, until Nobby put down his sandwich and squeaked – ‘Mum!’

‘Ere,’ came the familiar voice of Mokey Moke through the shadows.

‘Broughta vister,’ squeaked Nobby, with Buster adding, ‘Nice sprise ferya.’

‘Vister,’ squeaked Nobby again.

‘Oozat ven?’ called Mokey Moke.

All the mokes laughed. Once again, Furball was glad she hadn’t said anything to make her seem foolish.

‘Can’t guess!’ Mokey Moke was saying.

‘Real mystery! Now oo could it be?’ laughed Buster.

In the darkness there were squeakings from a number of mokes. The commotion set off a chorus of very high-pitched moke voices. The noise was almost like the song of the fevvas in the backyard which Furball had heard on her shed adventure.

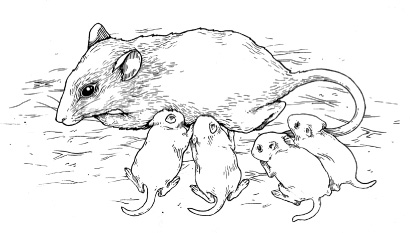

Mokey Moke was lying in an improvised nest. Furball, Nobby and Buster had scuttled the whole length of the underground passage beneath the kitchen floor. They had reached an area beneath the bottom of the stairs, leading out to the kitchen corridor, and through a gap in the bottom stair soft grey light glimmered on to the scene.

And where Mokey Moke lay in her nest, there were two tiny pinkish-grey mokes nestling at her stomach, sucking her milk. Beside them two other mokes, equally tiny, equally pink, were squeaking that it was their turn to feed.

‘Well ere’s a turn-up for the books, Mum,’ said Nobby.

‘Who’s vey ven?’ laughed Buster. ‘Arencha gointer intradjuice-us?’

‘These are the new Arrivals,’ said Mokey Moke proudly.

‘Only,’ said Nobby, ‘Some of us call em The Rivals.’

It was extraordinary. Furball looked at the thin, but beautiful, little moke babies and wondered where they had come from. Were these what Mokey Moke had been ‘spectin’?

‘Have you been to the pet shop?’ she asked politely.

All the mokes squawked with laughter.

‘Vat’s right,’ said Mokey Moke. ‘Reckon I got a good bargain, eh – gottem free.’

‘We brought you this seed sandwich,’ said Furball.

Almost before she had placed the sticky slab in the dust, mokes from all sides gathered round to grab and bite into it. She approached Mokey Moke and de-pouched some more, then held it out in her clean pink paws for her friend as she lay there, feeding her babies.

‘You’re a good pal, Furball,’ said Mokey Moke.

‘Said old Furball would see us right, Mum,’ said Nobby.

Then Mokey Moke explained that the mokes had become hungry when she couldn’t go with them on food raids. They had a rule – every moke for hisself. It meant that no moke depended on another for food. But in practice the young mokes relied on Mokey Moke to lead them, to show them the best places for supplies. And Mokey Moke kept them in good order. She’d organise two mokes as lookouts, and the others into climbing parties to fetch food from shelves. But when the food supply dried up, several of the mokes had gone missing, she’d said.

‘You must be worried,’ said Furball.

‘Not exactly,’ said Mokey Moke. ‘You can’t keep an eye on em all. Just you wonder where some on them get to.’ Then she looked down at her babies and said, ‘That’s enough for you two Arrivals. Ere. Gerroff. Let someone else ave-a suck for a change.’

‘Would they like some of this?’ asked Furball, holding out in her paw some of the sandwich she had de-pouched.

‘That’s kind of you, love – but leave it a while, eh. They’re a bit young for solids.’