Getting Past Yes

Negotiating as if implementation mattered. by Danny Ertel

IN JULY 1998, AT&T and BT announced a new 50/50 joint venture that promised to bring global interconnectivity to multinational customers. Concert, as the venture was called, was launched with great fanfare and even greater expectations: The $10 billion start-up would pool assets, talent, and relationships and was expected to log $1 billion in profits from day one. Just three years later, Concert was out of business. It had laid off 2,300 employees, announced $7 billion in charges, and returned its infrastructure assets to the parent companies. To be sure, the weak market played a role in Concert’s demise, but the way the deal was put together certainly hammered a few nails into the coffin.

For example, AT&T’s deal makers scored what they probably considered a valuable win when they negotiated a way for AT&T Solutions to retain key multinational customers for itself. As a result, AT&T and BT ended up in direct competition for business—exactly what the Concert venture was supposed to help prevent. For its part, BT seemingly out negotiated AT&T by refusing to contribute to AT&T’s purchase of the IBM Global Network. That move saved BT money, but it muddied Concert’s strategy, leaving the start-up to contend with overlapping products. In 2000, Concert announced a complex new arrangement that was supposed to clarify its strategy, but many questions about account ownership, revenue recognition, and competing offerings went unanswered. Ultimately, the two parent companies pulled the plug on the venture.1

Concert is hardly the only alliance that began with a signed contract and a champagne toast but ended in bitter disappointment. Examples abound of deals that look terrific on paper but never materialize into effective, value-creating endeavors. And it’s not just alliances that can go bad during implementation. Misfortune can befall a whole range of agreements that involve two or more parties—mergers, acquisitions, outsourcing contracts, even internal projects that require the cooperation of more than one department. Although the problem often masquerades as one of execution, its roots are anchored in the deal’s inception, when negotiators act as if their main objective were to sign the deal. To be successful, negotiators must recognize that signing a contract is just the beginning of the process of creating value.

During the past 20 years, I’ve analyzed or assisted in hundreds of complex negotiations, both through my research at the Harvard Negotiation Project and through my consulting practice. And I’ve seen countless deals that were signed with optimism fall apart during implementation, despite the care and creativity with which their terms were crafted. The crux of the problem is that the very person everyone thinks is central to the deal—the negotiator—is often the one who undermines the partnership’s ability to succeed. The real challenge lies not in hammering out little victories on the way to signing on the dotted line but in designing a deal that works in practice.

The Danger of Deal Makers

It’s easy to see where the deal maker mind-set comes from. The media glorifies big-name deal makers like Donald Trump, Michael Ovitz, and Bruce Wasserstein. Books like You Can Negotiate Anything, Trump: The Art of the Deal, and even my own partners’ Getting to Yes, all position the end of the negotiation as the destination. And most companies evaluate and compensate negotiators based on the size of the deals they’re signing.

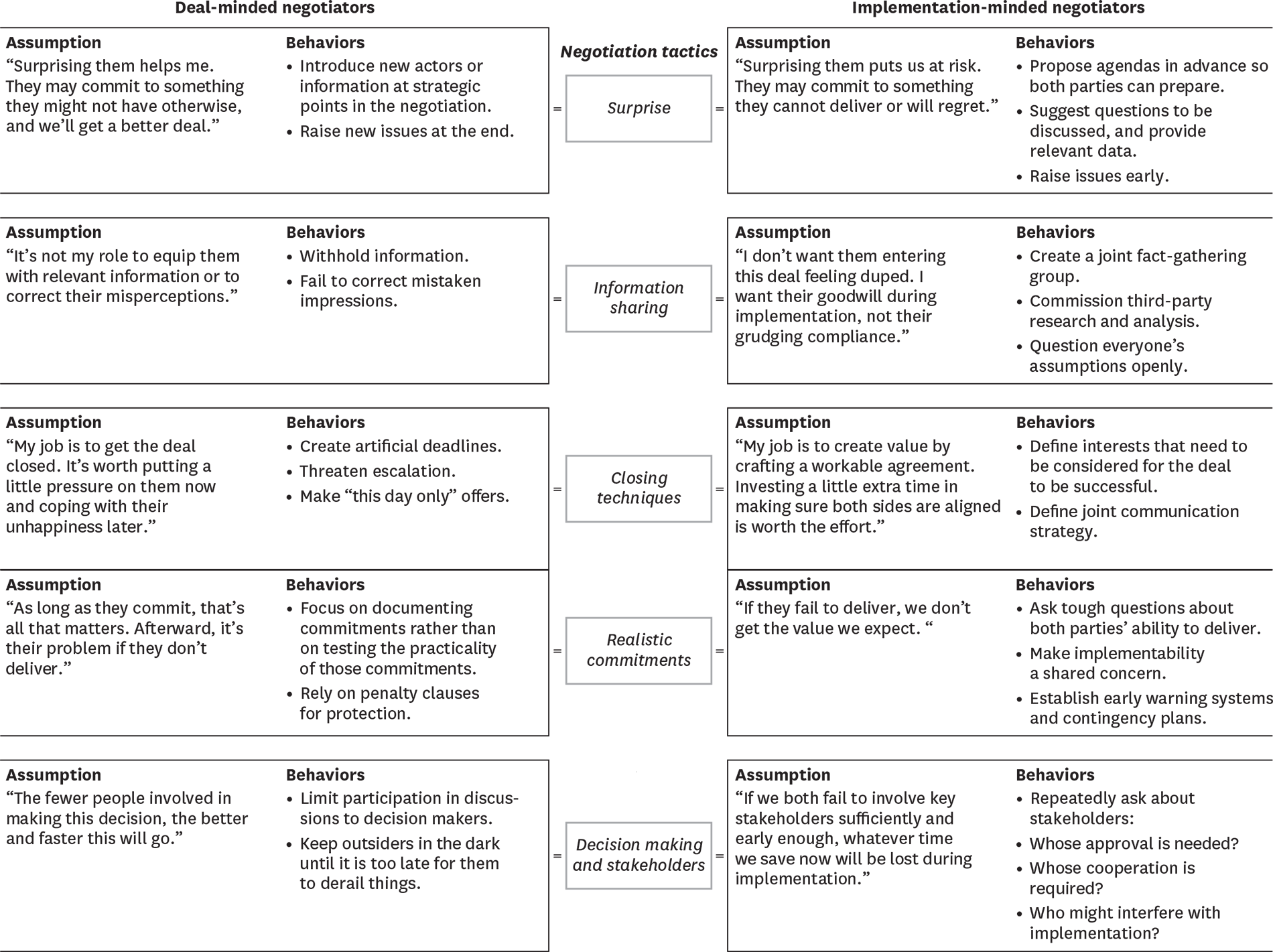

But what kind of behavior does this approach create? People who view the contract as the conclusion and see themselves as solely responsible for getting there behave very differently from those who see the agreement as just the beginning and believe their role is to ensure that the parties involved actually realize the value they are trying to create. These two camps have conflicting opinions about the use of surprise and the sharing of information. They also differ in how much attention they pay to whether the parties’ commitments are realistic, whether their stakeholders are sufficiently aligned, and whether those who must implement the deal can establish a suitable working relationship with one another. (For a comparison of how different mind-sets affect negotiation behaviors, see the exhibit “Deal-minded negotiators versus implementation-minded negotiators.”)

This isn’t to say deal makers are sleazy, dishonest, or unethical. Being a deal maker means being a good closer. The deal maker mind-set is the ideal approach in certain circumstances. For example, when negotiating the sale of an asset in which title will simply be transferred and the parties will have little or no need to work together, getting the signatures on the page really does define success.

But frequently a signed contract represents a commitment to work together to create value. When that’s the case, the manner in which the parties “get to yes” matters a great deal. Unfortunately, many organizations structure their negotiation teams and manage the flow of information in ways that actually hurt a deal’s chances of being implemented well.

An organization that embraces the deal maker approach, for instance, tends to structure its business development teams in a way that drives an ever growing stream of new deals. These dedicated teams, responsible for keeping negotiations on track and getting deals done, build tactical expertise, acquire knowledge of useful contract terms, and go on to sign more deals. But they also become detached from implementation and are likely to focus more on the agreement than on its business impact. Just think about the language deal-making teams use (“closing” a deal, putting a deal “to bed”) and how their performance is measured and rewarded (in terms of the number and size of deals closed and the time required to close them). These teams want to sign a piece of paper and book the expected value; they couldn’t care less about launching a relationship.

The much-talked-about Business Affairs engine at AOL under David Colburn is one extreme example. The group became so focused on doing deals—the larger and more lopsided the better—that it lost sight of the need to have its business partners actually remain in business or to have its deals produce more than paper value. In 2002, following internal investigations and probes by the SEC and the Department of Justice, AOL Time Warner concluded it needed to restate financial results to account for the real value (or lack thereof) created by some of those deals.2

The deal maker mentality also fosters the take-no-prisoners attitude common in procurement organizations. The aim: Squeeze your counterpart for the best possible deal you can get. Instead of focusing on deal volume, as business development engines do, these groups concentrate on how many concessions they can get. The desire to win outweighs the costs of signing a deal that cannot work in practice because the supplier will never be able to make enough money.

Think about how companies handle negotiations with outsourcing providers. Few organizations contract out enough of their work to have as much expertise as the providers themselves in negotiating deal structures, terms and conditions, metrics, pricing, and the like, so they frequently engage a third-party adviser to help level the playing field as they select an outsourcer and hammer out a contract. Some advisers actually trumpet their role in commoditizing the providers’ solutions so they can create “apples to apples” comparison charts, engender competitive bidding, and drive down prices. To maximize competitive tension, they exert tight control, blocking virtually all communications between would-be customers and service providers. That means the outsourcers have almost no opportunity to design solutions tailored to the customer’s unique business drivers.

The results are fairly predictable. The deal structure that both customer and provider teams are left to implement is the one that was easiest to compare with other bids, not the one that would have created the most value. Worse yet, when the negotiators on each side exit the process, the people responsible for making the deal work are virtual strangers and lack a nuanced understanding of why issues were handled the way they were. Furthermore, neither side has earned the trust of its partner during negotiations. The hard feelings created by the hired guns can linger for years.

The fact is, organizations that depend on negotiations for growth can’t afford to abdicate management responsibility for the process. It would be foolhardy to leave negotiations entirely up to the individual wits and skills of those sitting at the table on any given day. That’s why some corporations have taken steps to make negotiation an organizational competence. They have made the process more structured by, for instance, applying Six Sigma discipline or community of practice principles to improve outcomes and learn from past experiences.

Sarbanes-Oxley and an emphasis on greater management accountability will only reinforce this trend. As more companies (and their auditors) recognize the need to move to a controls-based approach for their deal-making processes—be they in sales, sourcing, or business development—they will need to implement metrics, tools, and process disciplines that preserve creativity and let managers truly manage negotiators. How they do so, and how they define the role of the negotiator, will determine whether deals end up creating or destroying value.

Negotiating for Implementation

Making the leap to an implementation mind-set requires five shifts.

1. Start with the end in mind

For the involved parties to reap the benefits outlined in the agreement, goodwill and collaboration are needed during implementation. That’s why negotiation teams should carry out a simple “benefit of hindsight” exercise as part of their preparation.

Imagine that it is 12 months into the deal, and ask yourself:

Is the deal working? What metrics are we using? If quantitative metrics are too hard to define, what other indications of success can we use?

What has gone wrong so far? What have we done to put things back on course? What were some early warning signals that the deal may not meet its objectives?

What capabilities are necessary to accomplish our objectives? What processes and tools must be in place? What skills must the implementation teams have? What attitudes or assumptions are required of those who must implement the deal? Who has tried to block implementation, and how have we responded?

If negotiators are required to answer those kinds of questions before the deal is finalized, they cannot help but behave differently. For example, if the negotiators of the Concert joint venture had followed that line of questioning before closing the deal, they might have asked themselves, “What good is winning the right to keep customers out of the deal if doing so leads to competition between the alliance’s parents? And if we have to take that risk, can we put in mechanisms now to help mitigate it?” Raising those tough questions probably wouldn’t have made a negotiator popular, but it might have led to different terms in the deal and certainly to different processes and metrics in the implementation plan.

Most organizations with experience in negotiating complex deals know that some terms have a tendency to come back and bite them during implementation. For example, in 50/50 ventures, the partner with greater leverage often secures the right to break ties if the new venture’s steering committee should ever come to an impasse on an issue. In practice, though, that means executives from the dominant party who go into negotiations to resolve such impasses don’t really have to engage with the other side. At the end of the day, they know they can simply impose their decision. But when that happens, the relationship is frequently broken beyond repair.

Tom Finn, vice president of strategic planning and alliances at Procter & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, has made it his mission to incorporate tough lessons like that into the negotiation process itself. Although Finn’s alliance management responsibilities technically don’t start until after a deal has been negotiated by the P&G Pharmaceuticals business development organization, Finn jumps into the negotiation process to ensure negotiators do not bargain for terms that will cause trouble down the road. “It’s not just a matter of a win-win philosophy,” he says. “It’s about incorporating our alliance managers’ hard-won experience with terms that cause implementation problems and not letting those terms into our deals.”

Finn and his team avoid things like step-down royalties and unequal profit splits with 50/50 expense sharing, to name just a few. “It’s important that the partners be provided [with] incentives to do the right thing,” Finn says. “When those incentives shift, you tend to end up [with] difficulties.” Step-down royalties, for instance, are a common structure in the industry. They’re predicated on the assumption that a brand is made or lost in the first three years so that thereafter, payments to the originator should go down. But P&G Pharmaceuticals believes it is important to provide incentives to the partner to continue to work hard over time. As for concerns about overpaying for the licensed compound in the latter years of the contract, Finn asserts that “leaving some money on the table is OK if you realize that the most expensive deal is one that fails.”

2. Help them prepare, too

If implementation is the name of the game, then coming to the table well prepared is necessary—but not sufficient. Your counterpart must also be prepared to negotiate a workable deal. Some negotiators believe they can gain advantage by surprising the other side. But surprise confers advantage only because the counterpart has failed to think through all the implications of a proposal and might mistakenly commit to something it wouldn’t have if it had been better prepared. While that kind of an advantage might pay off in a simple buy-sell transaction, it fails miserably—for both sides—in any situation that requires a long-term working relationship.

That’s why it’s in your best interest to engage with your counterpart before negotiations start. Encourage the other party to do its homework and consult with its internal stakeholders before and throughout the negotiation process. Let the team know who you think the key players are, who should be involved early on, how you hope to build implementation planning into the negotiation process, and what key questions you are asking yourself.

Take the example of Equitas, a major reinsurer in the London market. When preparing for commutations negotiations—whereby two reinsurers settle their mutual book of business—the company sends its counterpart a thorough kickoff package, which is used as the agenda for the negotiation launch meeting. This “commutations action pack” describes how the reinsurer’s own commutations department is organized, what its preferred approach to a commutations negotiation is, and what stages it follows. It also includes a suggested approach to policy reconciliation and due diligence and explains what data the reinsurer has available—even acknowledging its imperfections and gaps. The package describes critical issues for the reinsurer and provides sample agreements and memorandums for various stages of the process.

The kickoff meeting thus offers a structured environment in which the parties can educate each other on their decision-making processes and their expectations for the deal. The language of the commutations action pack and the collaborative spirit of the kickoff meeting are designed to help the parties get to know each other and settle on a way of working together before they start making the difficult trade-offs that will be required of them. By establishing an agreed-upon process for how and when to communicate with brokers about the deal, the two sides are better able to manage the tension between the need to include stakeholders who are critical to implementation and the need to maintain confidentiality before the deal is signed.

Aventis Pharma is another example of how measured disclosure of background and other information can pave the way to smoother negotiations and stronger implementation. Like many of its peers, the British pharmaceutical giant wants potential biotech partners to see it as a partner of choice and value a relationship with the company for more than the size of the royalty check involved. To that end, Aventis has developed and piloted a “negotiation launch” process, which it describes as a meeting during which parties about to enter into formal negotiations plan together for those negotiations. Such collaboration allows both sides to identify potential issues and set up an agreed-upon process and time line. The company asserts that while “formally launching negotiations with a counterpart may seem unorthodox to some,” the entire negotiation process runs more efficiently and effectively when partners “take the time to discuss how they will negotiate before beginning.”

3. Treat alignment as a shared responsibility

If their interests are not aligned, and they cannot deliver fully, that’s not just their problem—it’s your problem, too.

Unfortunately, deal makers often rely on secrecy to achieve their goals (after all, a stakeholder who doesn’t know about a deal can’t object). But leaving internal stakeholders in the dark about a potential deal can have negative consequences. Individuals and departments that will be directly affected don’t have a chance to weigh in with suggestions to mitigate risks or improve the outcome. And people with relevant information about the deal don’t share it, because they have no idea it’s needed. Instead, the typical reaction managers have when confronted late in the game with news of a deal that will affect their department is “Not with my FTEs, you don’t.”

Turning a blind eye to likely alignment problems on the other side of the table is one of the leading reasons alliances break down and one of the major sources of conflict in outsourcing deals. Many companies, for instance, have outsourced some of their human resource or finance and accounting processes. Service providers, for their part, often move labor-intensive processes to web-based self-service systems to gain process efficiencies. If users find the new self-service system frustrating or intimidating, though, they make repeated (and expensive) calls to service centers or fax in handwritten forms. As a result, processing costs jump from pennies per transaction to tens of dollars per transaction.

But during the initial negotiation, buyers routinely fail to disclose just how undisciplined their processes are and how resistant to change their cultures might be. After all, they think, those problems will be the provider’s headache once the deal is signed. Meanwhile, to make requested price concessions, providers often drop line items from their proposals intended to educate employees and support the new process. In exchange for such concessions, with a wink and a nod, negotiators assure the provider that the buyers will dedicate internal resources to change-management and communication efforts. No one asks whether business unit managers support the deal or whether function leaders are prepared to make the transition from managing the actual work to managing the relationship with an external provider. Everyone simply agrees, the deal is signed, and the frustration begins.

As managers and employees work around the new self-service system, the provider’s costs increase, the service levels fall (because the provider was not staffed for the high level of calls and faxes), and customer satisfaction plummets. Finger-pointing ensues, which must then be addressed through expensive additions to the contract, costly modifications to processes and technology, and additional burdens on a communication and change effort already laden with baggage from the initial failure.

Building alignment is among negotiators’ least favorite activities. The deal makers often feel as if they are wasting precious time “negotiating internally” instead of working their magic on the other side. But without acceptance of the deal by those who are essential to its implementation (or who can place obstacles in the way), proceeding with the deal is even more wasteful. Alignment is a classic “pay me now or pay me later” problem. To understand whether the deal will work in practice, the negotiation process must encompass not only subject matter experts or those with bargaining authority but also those who will actually have to take critical actions or refrain from pursuing conflicting avenues later.

Because significant deals often require both parties to preserve some degree of confidentiality, the matter of involving the right stakeholders at the right time is more effectively addressed jointly than unilaterally. With an understanding of who the different stakeholders are—including those who have necessary information, those who hold critical budgets, those who manage important third-party relationships, and so on—a joint communications subteam can then map how, when, and with whom different inputs will be solicited and different categories of information might be shared. For example, some stakeholders may need to know that the negotiations are taking place but not the identity of the counterpart. Others may need only to be aware that the organization is seeking to form a partnership so they can prepare for the potential effects of an eventual deal. And while some must remain in the dark, suitable proxies should be identified to ensure that their perspectives (and the roles they will play during implementation) are considered at the table.

4. Send one message

Complex deals require the participation of many people during implementation, so once the agreement is in place, it’s essential that the team that created it get everyone up to speed on the terms of the deal, on the mind-set under which it was negotiated, and on the trade-offs that were made in crafting the final contract. When each implementation team is given the contract in a vacuum and then is left to interpret it separately, each develops a different picture of what the deal is meant to accomplish, of the negotiators’ intentions, and of what wasn’t actually written in the document but each had imagined would be true in practice.

“If your objective is to have a deal you can implement, then you want the actual people who will be there, after the negotiators move on, up front and listening to the dialogue and the give-and-take during the negotiation so they understand how you got to the agreed solution,” says Steve Fenn, vice president for retail industry and former VP for global business development at IBM Global Services. “But we can’t always have the delivery executive at the table, and our customer doesn’t always know who from their side is going to be around to lead the relationship.” To address this challenge, Fenn uses joint hand-off meetings, at which he and his counterpart brief both sides of the delivery equation. “We tell them what’s in the contract, what is different or nonstandard, what the schedules cover. But more important, we clarify the intent of the deal: Here’s what we had difficulty with, and here’s what we ended up with and why. We don’t try to reinterpret the language of the contract, but [we do try] to discuss openly the spirit of the contract.” These meetings are usually attended by the individual who developed the statement of work, the person who priced the deal, the contracts and negotiation lead, and occasionally legal counsel. This team briefs the project executive in charge of the implementation effort and the executive’s direct reports. Participation on the customer side varies, because the early days in an outsourcing relationship are often hectic and full of turnover. But Fenn works with the project executive and the sales team to identify the key customer representatives who should be invited to the hand-off briefing.

Negotiators who know they have to brief the implementation team with their counterparts after the deal is signed will approach the entire negotiation differently. They’ll start asking the sort of tough questions at the negotiating table that they imagine they’ll have to field during the postdeal briefings. And as they think about how they will explain the deal to the delivery team, they will begin to marshal defensible precedents, norms, industry practices, and objective criteria. Such standards of legitimacy strengthen the relationship because they emphasize persuasion rather than coercion. Ultimately, this practice makes a deal more viable because attention shifts from the individual negotiators and their personalities toward the merits of the arrangement.

5. Manage negotiation like a business process

Negotiating as if implementation mattered isn’t a simple task. You must worry about the costs and challenges of execution rather than just getting the other side to say yes. You must carry out all the internal consultations necessary to build alignment. And you must make sure your counterparts are as prepared as you are. Each of these actions can feel like a big time sink. Deal makers don’t want to spend time negotiating with their own people to build alignment or risk having their counterparts pull out once they know all the details. If a company wants its negotiators to sign deals that create real value, though, it has to weed out that deal maker mentality from its ranks. Fortunately, it can be done with simple processes and controls. (For an example of how HP Services structures its negotiation process, see the sidebar “Negotiating Credibility.”)

More and more outsourcing and procurement firms are adopting a disciplined negotiation preparation process. Some even require a manager to review the output of that process before authorizing the negotiator to proceed with the deal. KLA-Tencor, a semiconductor production equipment maker, uses the electronic tools available through its supplier-management website for this purpose, for example. Its managers can capture valuable information about negotiators’ practices, including the issues they are coming up against, the options they are proposing, the standards of legitimacy they are relying on, and the walkaway alternatives they are considering. Coupled with simple postnegotiation reviews, this information can yield powerful organizational insights.

Preparing for successful implementation is hard work, and it has a lot less sizzle than the brinksmanship characteristic of the negotiation process itself. To overcome the natural tendency to ignore feasibility questions, it’s important for management to send a clear message about the value of postdeal implementation. It must reward individuals, at least in part, based on the delivered success of the deals they negotiate, not on how those deals look on paper. This practice is fairly standard among outsourcing service providers; it’s one that should be adopted more broadly.

Improving the implementability of deals is not just about layering controls or capturing data. After all, a manager’s strength has much to do with the skills she chooses to build and reward and the example she sets with her own questions and actions. In the health care arena, where payer-provider contentions are legion, forward-thinking payers and innovative providers are among those trying to change the dynamics of deals and develop agreements that work better. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Florida, for example, has been working to institutionalize an approach to payer-provider negotiations that strengthens the working relationship and supports implementation. Training in collaborative negotiation tools and techniques has been rolled down from the senior executives to the negotiators to the support and analysis teams. Even more important, those who manage relationships with providers and are responsible for implementing the agreements are given the same training and tools. In other words, the entire process of putting the deal together, making it work, and feeding the lessons learned through implementation back into the negotiation process has been tightly integrated.

Most competitive runners will tell you that if you train to get to the finish line, you will lose the race. To win, you have to envision your goal as just beyond the finish line so you will blow right past it at full speed. The same is true for a negotiator: If signing the document is your ultimate goal, you will fall short of a winning deal.

The product of a negotiation isn’t a document; it’s the value produced once the parties have done what they agreed to do. Negotiators who understand that prepare differently than deal makers do. They don’t ask, “What might they be willing to accept?” but rather, “How do we create value together?” They also negotiate differently, recognizing that value comes not from a signature but from real work performed long after the ink has dried.

Originally published in November 2004. Reprint R0411C

Notes

1. For more perspectives on Concert’s demise, see Margie Semilof’s 2001 article “Concert Plays Its Last Note” on InternetWeek.com; Brian Washburn’s 2000 article “Disconcerted” on Tele.com; and Charles Hodson’s 2001 article “Concert: What Went Wrong?” on CNN.com.

2. See Alec Klein, “Lord of the Flies,” the Washington Post, June 15, 2003, and Gary Rivlin, “AOL’s Rough Riders,” Industry Standard, October 30, 2000, for more information on the AOL Business Affairs Department’s practices.