DO NOT THINK that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. 18I tell you the truth, until heaven and earth disappear, not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law until everything is accomplished. 19Anyone who breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do the same will be called least in the kingdom of heaven, but whoever practices and teaches these commands will be called great in the kingdom of heaven. 20For I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven.

Original Meaning

JOHN THE BAPTIST’S initial announcement of the forthcoming arrival of the kingdom of heaven brought tension between the religious establishment and the kingdom’s projected activity (3:7–12). Jesus’ implicit and explicit criticism of the religious establishment will bring increasing tension and outright opposition (12:22–32). At the center of that tension and opposition is the suspicion that Jesus is not fully orthodox in his commitment to the Old Testament. Thus, in his first major discourse in this Gospel, Jesus makes clear his understanding of and commitment to the Old Testament.

But he will not simply affirm one of the interpretative schools of thought. He will not offer just another application of the ancient law to his contemporary circumstances. Instead, he will give the authoritative interpretation of the Old Testament’s original intended meaning, elevating himself above all the rabbinic debates. These four verses provide the key to interpreting the SM, but also in many ways the key to understanding Jesus’ inauguration of the kingdom, and by extension, the understanding of Matthew’s purpose for writing his Gospel.

Fulfilling the law (5:17). Some might see Jesus’ announcement of the arrival of the kingdom of heaven (4:17) as though he is starting a new work that will bring him into conflict with the Old Testament Scriptures. But Jesus categorically declares, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets.” The expression “do not think” suggests that Jesus is countering a suspicion that he is attempting to set aside God’s former revelation with his announcement of the arrival of the kingdom of God.1 Such an attempt would be the ultimate mark of a heretic.2 So Jesus makes clear at the beginning of his teaching ministry that the arrival of the kingdom does not do away with God’s prior revelation through the Law and the Prophets.

The “Law” or “Torah” refers to the first five books of the Old Testament, called the Books of Moses or the Pentateuch. The “Prophets” includes the major and minor prophets of the Old Testament. The expression “the Law and the Prophets” (cf. 7:12; 11:13; 22:40; Rom. 3:21) is a way of referring to the entire Hebrew Scriptures. This is similar to the expressions “the Law of Moses, the Prophets and the Psalms” (Luke 24:44) or simply “the Law”3 (Matt. 5:18; 1 Cor. 14:21). Instead of doing away with what God had revealed about his will for his people in the Hebrew Scripture, Jesus’ purpose for his earthly ministry is wrapped up in this formula: “I have come to fulfill them.”4

In Matthew’s narrative, the term “fulfill” (pleroo) has already become an important indicator of Jesus’ significance in God’s historical program, because Jesus’ life and ministry fulfill Old Testament prophecies and expectations (e.g., 1:22–23; 2:15, 17–18, 23; 4:14–16). Throughout the New Testament, various other writers also point to the way that Jesus fulfills, for example, the Old Testament roles of prophet,5 priest,6 and king.7 But here Jesus points in an additional direction when he declares that he has come to fulfill all of Old Testament Scripture.

The idea of “fulfillment” is more than his obedience (i.e., keeping the law), although that is included. The context, especially as worked out in the “antitheses” to follow (5:21–48), indicates that Jesus not only fulfills certain anticipated roles, but also that his interpretation of the Scriptures completes and clarifies God’s intent and meaning through it.8 Everything that the Old Testament intended to communicate about God’s will and hopes and future9 for humanity finds its fullest meaning in Jesus. Jesus has come to actualize the Scripture and take his disciples to a deeper understanding of its intended meaning—and this in distinction from many Jewish leaders, who have misunderstood and misapplied the Scripture’s intent.10

The lasting validity of the Old Testament (5:18). Jesus emphatically affirms the lasting validity of “the Law” (the entire Hebrew Scriptures) as the revealed will of God for his people until the end of this age brings a consummation of all that God has purposed. The two “until” clauses in 5:18 are parallel and essentially synonymous, used to emphasize the lasting validity of the Old Testament. “Until everything is accomplished” also seems to include some features of “fulfillment” that point to Jesus’ consummation of specific Old Testament hopes; for example, in the antitheses Jesus reiterates the lasting validity of the Old Testament but does not make legally binding certain specific prescriptions (see comments on 5:33–37).

The Old Testament endures forever as a revelation of God’s will for humans throughout history until all is “accomplished.” While some elements of Scripture will be accomplished in Jesus’ ministry, the Old Testament remains a valid principle. For example, the teaching of death and the shedding of blood to atone for sin is no longer expressed through temple sacrifices but rather has been “fulfilled/accomplished” once for all in Christ’s atonement on the cross (cf. Heb. 9:11–14). Thus, this commandment from the Old Testament is no longer legally binding as a practice. Nevertheless, the Old Testament principle of penalty and payment for sin remains valid and needs to be taught and understood as God’s will.11

Therefore, Jesus confirms the full authority of the Old Testament as Scripture for all ages (cf. 2 Tim. 3:15–16), even down to the smallest components of the written text. Those components are the “smallest letter” (iota; KJV “jot”) of the Hebrew alphabet (yod) and “the least stroke of a pen” (keraia; KJV “tittle”), which most likely refers to a serif, a small hook or projection that differentiates various Hebrew letters.

This has implications for understanding Jesus’ view of the inspiration of Scripture, which extends to the actual words, even letters and parts of letters. This is in accord with a “verbal plenary” view of inspiration; that is, the very words, and all of the words, of Scripture are inspired. Scripture does not simply contain the Word of God; the words of Scripture are the very Word of God.12

Doing and teaching the commandments (5:19). The consequences of one’s treatment of the Old Testament are immense. The rabbis recognized a distinction between “light” and “weighty” Old Testament commandments and advocated obedience to both (m. ʾAbot 2:1; 4:2). Light commandments are those such as the requirement to tithe on produce (cf. Lev. 27:30; Deut. 14:22), and weighty commandments are those such as profaning the name of God, misusing the Sabbath, or refusing to enact social justice (Ex. 20:2–8; Mic. 6:8). Since the Old Testament remains the valid expression of God’s will, even down to the “jot” and “tittle,” Jesus likewise demands a commitment to both the least of the commandments as well as the greatest, but at the same time condemns those who pervert the light into weighty (cf. Matt. 23:23).13

Jesus directs his comments specifically to his own followers. The “least” and “great in the kingdom of heaven” are those who have responded to his announcement of the gospel of the kingdom. Jesus drives home the binding authority of Scripture. Since he does not “abolish” the Law and the Prophets but fulfills them (5:17), his disciples likewise must not “abolish” or “break”14 the commandments but must instead practice and teach them (5:19). The wordplay here warns his disciples how to conduct themselves with regard to the Old Testament as he now fulfills it. The entire Old Testament is the expression of God’s will, but it is to be obeyed and taught from the perspective of how Jesus “fulfills” it through his interpretation of its intent and meaning. A disciple’s status in the kingdom of heaven accords with whether one trifles with the revealed will of God or one obeys and teaches it as truly the Word of God.

The rank of “least” should not be taken to indicate exclusion from the kingdom, because in the next verse Jesus makes a distinction between those inside and outside of the kingdom. “Least” and “great” are ways to acknowledge in this present life those who have been faithful in word and deed to the revealed will of God as it is taught by Jesus.

“Inside-out” righteousness (5:20). From a warning and commendation to his disciples, Jesus next turns his attention to the broader audience—those who are not in the kingdom of heaven. “For I tell you that unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven” (5:20). This may have been Jesus’ most shocking statement, because the teachers of the law and the Pharisees were the epitome of ethical righteousness.

The “teachers of the law” or scribes (grammateus) were not only curators of the text of the Old Testament, but they also taught the Law (7:29), held themselves responsible to interpret and preserve the Law (Mark 7:5–8), elaborated doctrine from the Law (Matt. 17:10), and gathered around themselves disciples whom they could train to carry on the profession and their teachings. Today the equivalent might be a professor or scholar of biblical studies and theology. The “Pharisees” (see comment on 3:7) were members of the sect that was committed to fulfilling the demands of the Old Testament through their elaborate oral tradition. Their scrupulous adherence to the written and oral law was legendary in Israel, yet Jesus says that it does not gain them entrance to the kingdom of heaven.

But how could anyone possibly surpass their righteousness? If the scribes and the Pharisees had not gained entrance, what hope was there for anyone else? Does this mean an intensification of a doctrine of salvation by works? Does this mean that one must exceed the scribes and the Pharisees in performing all the 613 commandments15 and do them one better? No, replies Jesus. His disciples are called to a different kind and quality of righteousness, not an increased quantity. As was recognized in both Jesus’ interaction with John the Baptist (3:15) and the statement of the Beatitudes (5:6), righteousness in the preaching of Jesus is not primarily a personal attainment of ethical purity. Righteousness belongs in the realm of grace. Jesus’ proclamation of good news is that the kingdom of heaven is now available to those who respond to him. God’s saving activity has arrived on the earthly scene to deliver his people, and this will produce a radical change in their lives.16

The shock of that declaration strips away current precedents for gaining favor with God and serves both as an introduction to the “antitheses” to follow (5:21–48) and as a tacit disclosure of the central principle of life in the kingdom of heaven, namely, that kingdom righteousness operates from the inside-out, not from the outside-in. This is not a new principle, however. God’s people knew that external acts of righteousness could not take away sin or gain favor with God unless they were preceded by a repentant heart. Psalm 51 is perhaps the archetype, where David seeks inner cleansing and purification of his heart after his dreadfully sinful affair with Bathsheba (Ps. 51:2, 7, 10). His understanding of the inside-out operation is explicit:

You do not delight in sacrifice, or I would bring it;

you do not take pleasure in burnt offerings.

The sacrifices of God are a broken spirit;

a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise. (Ps. 51:16–17)

David did later offer sacrifices and offerings and he did receive God’s favor, but he knew they had to be preceded by inner repentance and God’s work of cleansing and purification.

Yet throughout Israel’s history there was a tendency to reverse the operation, as was the case with the scribes and Pharisees of Jesus’ day. The assumption seemed to be that if one worked hard enough to clean up the outside, then the inside was automatically clean. Jesus later condemns this procedure explicitly when he says:

Woe to you, teachers of the law and Pharisees, you hypocrites! You are like whitewashed tombs, which look beautiful on the outside but on the inside are full of dead men’s bones and everything unclean. In the same way, on the outside you appear to people as righteous but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and wickedness. (Matt. 23:27–28).

Since entrance into the kingdom of heaven is not gained by external acts of righteousness, Jesus leads the audience to recognize that people must seek a different kind of righteousness—an inner righteousness that begins with a transformation of the heart, an undertaking David knew could only be accomplished by God (Ps. 51:10).

The arrival of the kingdom of heaven produces spiritual transformation in the disciple’s heart, which will ultimately produce transformation in the disciple’s external ethical life (see comments on 15:16–20). If entrance into the kingdom of heaven can only be accomplished by an inner work of transformation, so also personal growth within the kingdom must proceed from inside to out. That principle underlies the next series of examples Jesus uses to explain how he fulfills the Old Testament. His disciples themselves will fulfill God’s intention and will (as revealed in Scripture) as they conform their inner life to his Word and then have that inner transformation guide their external behavior.

Without doubt, Jesus’ declaration in 5:20 is an interpretive key to the entire Sermon on the Mount and, by extension, to life in the kingdom of heaven. It is the same reality that underlies Paul’s understanding of justification and sanctification. So Jesus in no way sets aside or abolishes the Law, but he affirms and fulfills its complete authority. In the antitheses to follow, Jesus contrasts his internal, spiritual interpretation with the external, legalistic interpretation of the Pharisees, which dead-ends in an external, superficial self-righteousness.

Bridging Contexts

BASED ON THE stringent attitude toward God’s law found in these words of Jesus, critical scholars have often tried to pit Matthew and Paul against each another, as though Paul advocated a gospel of grace that was antinomian, which Matthew intentionally countered with a gospel of law.17 But the contrast between Paul and Matthew is overplayed. While Matthew records Jesus’ sayings that uphold the binding validity of the law (5:17–20), he also has strong language of rebuke for the Pharisees who legalistically applied the Old Testament in such a way that they were cutting people off from the kingdom of heaven (e.g., 23:13–15). Matthew also focuses on Jesus’ message of transformation from the heart, not salvation by works (e.g., 15:1–20).

Paul likewise upholds the law as holy, righteous, and good (Rom. 7:12) and has strong words of condemnation for the Judaizing legalists (e.g., Gal. 1:8), focusing on salvation by grace alone (e.g., Eph. 2:8–9). Both Matthew and Paul go back to Jesus for the declaration that the Old Testament Scripture is the written, revealed will of God. The Old Testament is and will remain Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16), but Jesus brings it to its intended meaning and goal.

Fulfilling the Law. Matthew has prepared his readers well for Jesus’ staggering pronouncement, “I have not come to abolish the Law and the Prophets . . . but to fulfill them,” by consistently pointing to the way that Jesus fulfills certain Old Testament prophecies or themes. Now comes the overwhelming pronouncement that Jesus fulfills all of the Old Testament. Rampant must have been the rumors that Jesus and his followers had set aside the Old Testament. So Matthew points out directly to his readers that Jesus fulfills the Old Testament.

But the way in which Jesus fulfills the Law here in 5:17–20 takes us in a slightly different direction than in prophecy-fulfillment in the first two chapters. There, specific Old Testament prophecies of a coming messianic deliverer were fulfilled in Jesus’ life and ministry (1:22–23, 2:5–6, 15, 17–18, 23). Here Jesus brings to fulfillment all that the Old Testament had revealed about God’s will for humanity. (1) This means that Jesus’ life of perfect obedience to the will of God as revealed in the law enables him to be the perfect sacrifice for sins in his death. (2) Moreover, his obedience provides the means by which his disciples are able to live lives of obedience to God’s law, because Jesus will soon assist his followers in understanding and obeying God’s original intention of his law.

It will not be enough to conform one’s behavior to an external obedience of any particular law. Rather, Jesus’ disciples will understand the realities to which the Law pointed and will have a heart transformation and obedience that is accomplished through new covenant life in the Spirit. The pathway to greatness in the kingdom of heaven is through obeying and teaching his commands (5:19), which is an overarching characteristic of Great Commission disciples (28:19–20). “The command to live under God’s dominion, first given to Adam and Eve at creation, can therefore be restored with the inauguration of the kingdom, since the power of God’s presence in our midst is the dawning of the new creation. Jesus’ demands flow from his gifts.”18

This is an increasingly clear indication of the arrival of those new covenant promises. The prophet Ezekiel had prophesied:

I will sprinkle clean water on you, and you will be clean; I will cleanse you from all your impurities and from all your idols. I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit in you and move you to follow my decrees and be careful to keep my laws. (Ezek. 36:25–27; cf. Jer. 31:31–34)

Jesus guides his disciples into the true intention of God’s law, which focuses on inner righteousness as opposed to mere external righteousness. They gain entrance to the kingdom by repenting and confessing their sins (cf. 3:1–6; 4:17), which allows the Spirit to enter into their life to bring purification through applying Jesus’ atoning righteousness to their heart. In this way, Jesus’ disciples are more righteous than the scribes and the Pharisees, because they have received regeneration as they enter the kingdom.

Moreover, Jesus’ disciples progress in righteousness through their transformation into the image of Christ. This statement lays the foundation for the later New Testament doctrines of justification (imputed righteousness) and sanctification (imparted righteousness), which will be special emphases of the former “righteous” Pharisee, the apostle Paul.

Small wonder Paul, that most faultless of Pharisees (Phil. 3:4–6), when he came to understand the Gospel of Christ, considered his spiritual assets rubbish. His new desire was to gain Christ, not having a righteousness of his own that comes from the law, but one which is from God and by faith in Christ (Phil. 3:8f.).19

Contemporary Significance

THE CHRISTIAN’S RELATION to the law. The issues surrounding the Christian’s relationship to the Old Testament Scripture (Law) are complex. Some contend that none of it applies to Jesus unless it is explicitly reaffirmed in the New Testament, while others say that all of the Old Testament applies unless it is explicitly revoked in the New Testament.20 Both of these extremes should be avoided in the light of Jesus’ statements in 5:17–20. While these issues are beyond what we can address here, some basic principles can be suggested.

(1) The law is a revelation of God’s will for humanity. It reveals a standard of God’s perfect righteousness. We trifle with God’s will if we set aside some aspects of his Word. For example, it may be commendable to oppose abortions, but when antiabortion activists resort to violence and murder, they have set aside God’s commands.

(2) We need to understand God’s purpose for giving his law if we are to rightly understand the law itself. The law had several purposes. It was designed to instruct God’s people in his will so that they might fulfill his purpose for them as “a kingdom of priests and a holy nation” (Ex. 19:6). But they were not to rely on its requirements as the means of finding forgiveness (Ps. 51:14–17). The law was given to point out humanity’s sinfulness and need for God (Rom. 7:7) and to lead humanity to Christ, by whom they will be justified by faith (Gal. 3:24).

(3) When reading the Gospels in general and the antitheses in particular (Matt. 5:21–48), we must keep in mind that Jesus is here objecting to misinterpretations of the law, not the law itself. A tendency existed in Pharisaic Judaism to make their interpretations and traditions just as binding as the law itself. Jesus rejected their practices, not the law. He continued to uphold the law as the will of God.

(4) Jesus fulfilled the law and proved to be the perfect God-man, who is therefore able to become the means of our justification or right standing with God (Matt. 5:17–20; Rom. 5:18–21; Heb. 5:7–10). Therefore, we are not under the law as a means of gaining salvation.

(5) At the same time, Jesus is the interpreter of the law, showing what is binding principle and what is the temporary symbolic ritual (Matt. 12:1–8; Heb. 9:11–10:13). We should seek Christ’s mind for a proper interpretation and application of the law and understand the Old Testament in the light of the new covenant he inaugurates. He emphasized that ultimately the law was given to aid humans to live life the way God intended it to be lived, not to keep us under a binding set of religious rules (Matt. 12:3–5, 9–14). As Jesus gives his interpretation of the law, he reveals its intent and motive that were lost behind the external legalism of the scribes and Pharisees. He then demonstrates how principles of the law are valid guidelines to show God’s will for his people (5:21–48).21

(6) Jesus demonstrates that the entire Old Testament hangs on love for God and neighbor (22:38–39), which truly brings to fulfillment all of the Law. The “law of love” becomes an important key to determine how the Christian is to live out the will of God (5:21, 27, 38, etc.).

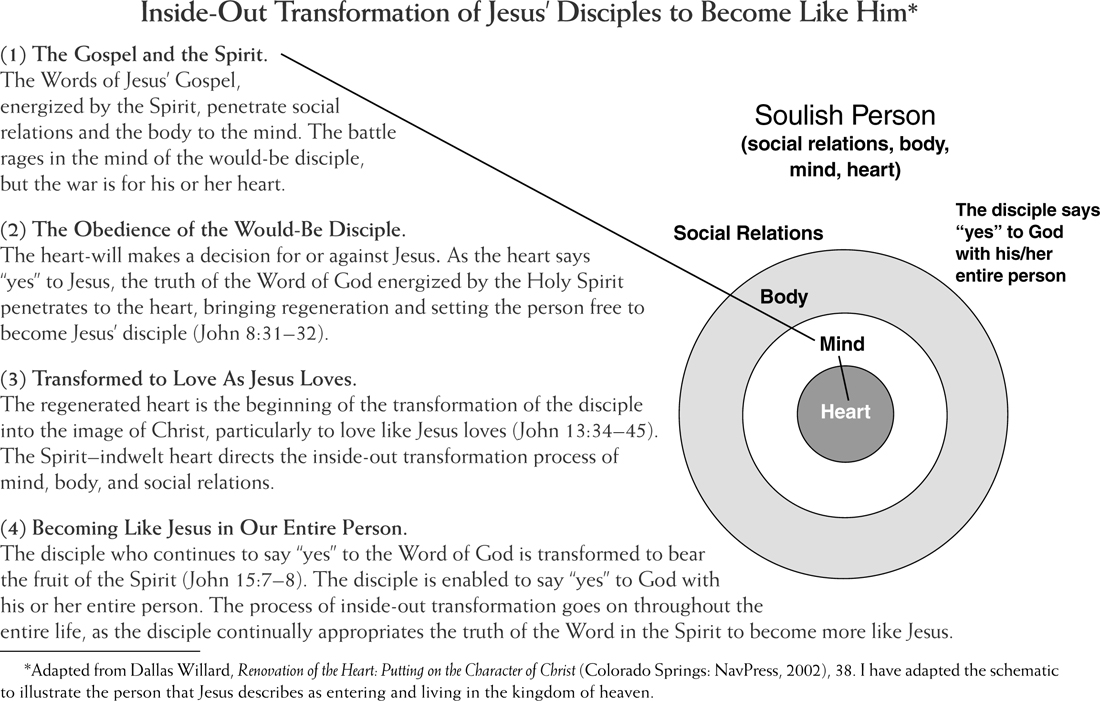

Inside-out transformation. The “inside-out” nature of Jesus’ teaching on kingdom life can be illustrated by thinking of his disciple as concentric layers that eventually penetrate to the core of the person. We are “soulish persons,” which indicates that we are a complex of immaterial and material realities. Our outermost layer consists of social relations. What I know first about a person are the relationships I share with or see the person engaged in, whether in a class, or in a family, or on the street. The next inward layer is the body, including what the person wears, how she carries herself, the way she talks, what she looks like, and so on. The next inward layer is the mind of the person. The mind is where the person reasons, considers emotions, and experiences spiritual realities. Then the innermost core of the person is the heart, which includes the person’s will and spirit.

The gospel Jesus preached was energized by the Spirit of God, penetrating through social relations and the body to the mind of the listener. Jesus’ teaching, logic, and appeal to the person were all at odds with those of the religious leaders who opposed him. At the same time, the Spirit of God convicts and draws the person, yet the forces of evil try to persuade the person that Jesus’ gospel message is a fraud. The battle is waged in the mind, but the war is for the heart. If the person says “yes” to Jesus in the will of his or her heart, the Word of God energized by the Spirit penetrates to the heart, bringing new covenant transformation—justification, regeneration, and renewal of life. The person has become a disciple of Jesus and entered the kingdom of heaven.

This attempts to illustrate what Jesus meant when he said that “unless your righteousness surpasses that of the Pharisees and the teachers of the law, you will certainly not enter the kingdom of heaven” (5:20). The innermost core of the disciple has experienced new covenant transformation, which includes justification (declared forensically righteous before God) and the beginnings of sanctification (the experience of personal growth in righteousness). This far surpasses the righteousness of the scribes and Pharisees, which was external and self-produced.

As the disciple continues to respond obediently to the Word of God taught and preached by Jesus and energized by the Spirit, the newly transformed heart directs the transformation of the person from the inside to the outside. The heart-will of the person in the power of the indwelling Spirit directs the renewing of the mind (cf. Rom. 12:1–2), the disciplining of the body (1 Cor. 6:12–20), and the purifying of social relations (1 Cor. 5:9–13; Heb. 10:24–25) so that the disciple says “yes” to God with his or her entire “soulish person.” The disciple bears the fruit of the Spirit in a life given to God that is being transformed to be like Jesus.

The schematic on the following page attempts to illustrate these truths. This is the process of discipleship, in which the truth of the gospel sets a person free to become Jesus’ disciple. As he or she continues to compare the words of the world to the words of Jesus, the person is truly free to grow in discipleship to Jesus (John 8:31–32). The Spirit of God takes up residence in the life of the disciple, producing Christlike characteristics, including especially love (John 13:34–35) and the fruit of the Spirit (John 15:7–8). As we look at the SM unfold, this schematic will help us to appropriate Jesus’ teaching and promote growth to be transformed more and more like him.