5

Public Debate

This final chapter is focused on the public debates that occur when everyday citizens come together to discuss resonant social and political issues. While we will consider conversations unfolding in hybrid and embodied spaces, we are most interested in online debate, and the impact digital media have on public discourse. Drawing from the saga surrounding UK research vessel Boaty McBoatface, we will illustrate how the blending and clashing of groups within groups, publics within publics, can engender profound discord, confusion, and the unfair marginalization of some and unfair aggrandizement of others. Simultaneously (and there is always a simultaneously), we will show that there's vibrancy in this complication. Even if it represents fracture and contestation, a public multiplicity can empower marginalized identities, facilitate a greater range of public expression, and ultimately strengthen the democratic process.

The ambivalent claim that public multiplicity complicates democratic participation and also provides the raw materials for such participation is augmented by two further points of ambivalence: the evil twins of conflict and unity and affect and rationality, each collapsing under the weight of the other. To demonstrate the conceptual bedevilment of both, we'll focus on the highly contentious and often highly bizarre 2016 US Presidential election, with special attention paid to the ultimately successful campaign of gaudy gilded businessperson, actual reality television villain, and as of, well, yesterday (these words were typed just before the book's final submission deadline on November 9, 2016), President-Elect Donald J. Trump.11 We will then explore how the ambivalence of public debate persists across eras and degrees of mediation, keeping our side eyes on Trump all the while. True to form, we will follow this discussion with the rejoinder that, not so fast, digital mediation sends ambivalence into hyperdrive – one final look at our brave new world, with nothing new under the sun.

Publics and their problems

On March 17, 2016, the UK's National Environment Research Council (NERC) took a pretty big risk: it turned to the public to help name its state-of-the-art £200 million polar research vessel. To that end, NERC set up a site, NameOurShip.nerc.ac.uk, and invited interested parties across the globe to submit something “catchy” to call the boat. The campaign was an immediate hit. “We've had thousands of suggestions made on the website since we officially launched,” NERC's director of corporate affairs Alison Robinson revealed in an interview with NPR's Laura Wagner (2016). “Many of them reflect the importance of the ship's scientific role by celebrating great British explorers and scientists. Others are more unusual but we're pleased that people are embracing the idea in a spirit of fun.” One of these names, submitted by former BBC Radio host James Hand, was spirited and fun indeed: Boaty McBoatface. This particular name proved so popular with voters that, in the days following its submission, the NERC site nearly crashed – its servers could barely contain the public's enthusiasm (Walker 2016). Unsurprisingly, Boaty McBoatface ended up winning the competition in a landslide, garnering over 124,000 votes.

While voters and rubberneckers alike celebrated Boaty's triumph, NERC wasn't amused. Echoing broadcaster and naturalist Sir David Attenborough's insistence that the research vessel deserved a more prestigious name – particularly one that “lasts longer than a social media news cycle” – UK Science Minister Jo Johnson indicated that NERC would sidestep the poll's results and instead choose a more traditional name for the boat (Plunkett 2016). In protest, apparent Boaty supporters took to the internet. They posted to the #JeSuisBoaty Twitter hashtag, a riff on 2015's freedom-of-speech-focused #JeSuisCharlie, which spread in the wake of the tragic mass shooting that occurred in the offices of satirical French newspaper Charlie Hebdo. They changed their Facebook profile pictures to an image of a boat captioned with the statement, “I Sail with Boaty.” They lashed out at NERC authorities, as geek-chic celebrity Wil Wheaton (2016) did when he addressed Boaty's demise on his popular tumblog. “fuck you, you stupid goddamn science minister,” he wrote after NERC sank Boaty. “If you put it up for a vote on the Internet, and you don't get ‘HMS 420 Moot Fucked Your Mom’ as the winner, consider yourself lucky, and honor the fucking vote.”12

Journalists entered the discursive fray as well, adding their own spin to participants' indignation. In a cheeky article on the controversy, Guardian contributor Stuart Heritage (2016) connects the defeat to broader tramplings of public will. “We all need to face up to the desperate fact that our voices are doomed to be forever unheard,” he writes. “The anti-war demonstration in 2003 was ignored by the government. Protests and marches and movements are routinely ignored by the government. And now we can't even give a jaunty name to a sodding boat without the government blowing it up in our faces.” Heritage concedes that the name Boaty McBoatface is an “infuriatingly twee …godawful name for a boat” in no way befitting its mission. But that's not the point. The point is that the people voted for Boaty, and those votes should be respected.

For Heritage, “the people” is a singular collective, existing in clear opposition to the fun-ruining, democracy-thwarting powers that be. However, the actual participant breakdown in the Boaty saga – as in all cases featuring discussions of “the people” or “the public” – is more complicated than that. Instead of being some monolithic, undifferentiated mass, “the public” is in fact comprised of a number of different perspectives and collectives, a cacophony of voices and interests constituting multiple publics. Even within smaller, subset publics unified by some common factor (akin to a bounded folk group), each seemingly singular public can always be broken down into further publics unified by more specific common factors. Singular framings of “the people” and “the public” obscure how many publics there are, or could be, depending on what common factor one chooses to foreground; the public sphere is at once nesting doll, spider web, and ball pit of overlapping Venn diagrams. And these are not always – in fact, these are rarely – wholly harmonious points of difference.

In the case of the Boaty debates, some participants seemed to genuinely care about the outcome and perceived threat to populist expression. Others were more ambivalent in their creation, circulation, and transformation of Boaty content on Twitter and Facebook. Perhaps they participated for a laugh, perhaps to get a reaction from their followers, perhaps simply because that's what people were playing with on Twitter and Facebook that day. And still others took a more contrarian stance, or refused to take a stance either way. Because, like Heritage says, it's a sodding boat.

Communication scholars Robert Asen and Daniel C. Brouwer (2001) argue that, chaotic as these publics might be, the resulting clash of motives and perspectives creates important opportunities for dissent via counterpublics. Nineteenth-century political philosopher John Stuart Mill anticipates a similar point when he frames divisive “sectarian” debate as an opportunity to “share the truth” ([1859] 2009, 47) between groups. This sharing, according to Mill, can inspire more nuanced arguments, more critical thinking, and more self-reflection, in turn allowing “disinterested bystanders,” i.e. everyday citizens not swept up in whatever discursive flurry, to arrive at a more perfect truth. In the case of Boaty, this more perfect truth could be achieved by weighing UK Science Minister Jo Johnson's insistence that the name of a £200 million polar research vessel shouldn't be an internet punchline and Wil Wheaton's reminder that, no fuck you, it really could have been worse and Sir David Attenborough's charge to grow up, science is serious and Stuart Heritage's conviction that the will of the people must be respected, even if the people are, as he says, “idiots.” Democracy at its finest.

In the end, NERC asserted its will; on May 6, the Council announced that the boat would be christened the RSS Sir David Attenborough (the same man who protested against the Boaty submission on the grounds that the vessel's namesake should befit its station – a criterion met, apparently, by himself). They did, however, throw Boaty supporters a life raft, announcing that Boaty McBoatface would live on as the name of a “high-tech remotely operated undersea vehicle” affixed to the main vessel (Chappell 2016). The most vocal Boaty supporters remained unsatisfied; in response to NERC's tweet announcing Boaty's reboot as Subby McSubface, commenters on Twitter lamented the failure of democracy, accused NERC of “cowardly desperation,” and suggested that they might as well be living in totalitarian regime North Korea. One group even formally petitioned that Sir David Attenborough change his name to Boaty McBoatface (Doctorow 2016).

Boaty's torpedoing illustrates the limits of utopian democratic framings. Within the public sphere, different publics and different voices within those publics can share their truths. But just because someone is speaking doesn't mean that others can or are willing to hear. Not all citizens – and not all publics – are treated with equal respect, or afforded equal volume.

There are two basic factors contributing to this discrepancy. The first is the fact that some people are simply louder and pushier than others. This is certainly true in contemporary online debates; the vast majority of public participation online is produced by what Todd Graham and Scott Wright (2014) call “super participants,” a highly polarized minority. Small in numbers as they might be, these super participants are especially loud and especially visible, and can easily drown out dissenting perspectives, thus skewing – or seeming to skew – a particular debate. In the case of Boaty McBoatface, yes, there were a lot of people shouting rude and sarcastic and sometimes, admittedly, pretty funny things on Twitter. But there were many more people, millions more people, who responded to the story with a shruggie, if they bothered to respond at all – which was certainly not the impression communicated by many Twitter feeds.

But loudness isn't the only explanation worth considering. Also critical to this picture is access, and the agency tied to that access. Specifically, those who have an existing audience and platform – stemming from who that person is, what kinds of experiences they've had, and where they fit within the socioeconomic hierarchy – are more likely to command attention. Wil Wheaton, for example, enjoys a large audience across multiple social media platforms, and so his perspective, even if it was an extreme perspective, garnered much more attention than those of participants who were more moderate but less known. Relatedly, the positions of power or privilege one occupies directly influence who is willing to listen, and more importantly, who is able to take action as a result. Regarding Boaty, when it came time to make a decision, the more traditional seat of public power – literally the public face of the British Crown – was able to set the agenda. They had the power to say “yeah actually no” to Boaty supporters, despite the fact that those supporters considerably outnumbered NERC representatives. Regardless of how compelling Pro-Boaty publics might have been (or not, Wil Wheaton), those voices were stifled by the establishment, and forced to begrudgingly accept the high-tech remotely operated undersea vehicle consolation prize.

Beyond illustrating the multiplicity of publics, the Boaty McBoatface saga reveals that public debate is predicated on ambivalence; it's a process that empowers and marginalizes in equal measure. And beneath this already highly ambivalent umbrella is, unsurprisingly, more ambivalence. The following section will take a deeper dive into these points of ambivalence, highlighting how quickly the conflict/unity and affect/rationality binaries fall apart when considering the complex realities of public debate.

The evil twins of public debate

The fundamental multiplicity of public debate is the engine behind its ambivalence: the fact that many groups (within groups, within groups) with many different, often clashing, motives can support, reassure, and embolden insiders while simultaneously condemning, antagonizing, and even injuring outsiders. Complicating this picture, and echoing discussions of identity play in Chapter 2, these demarcations are not stable across time; insiders can become outsiders, and outsiders can become insiders, depending on even the slightest changes within groups and also within the individuals who comprise them. However us and them might be configured in a given moment, a further layer of ambivalence is engendered by the apparent binaries of conflict and unity and affect and rationality. Each component of each set represents the flip side of the other; each component equally inhabits both sides of the coin. And each has for generations played the role of the bad twin and the good twin within public debate, in the process carving a highly ambivalent public sphere that both facilitates and hinders democratic participation.

The following two sections will focus on these two sets of evil twins, drawing from cases related to the 2016 US Presidential election. Not only do these examples illustrate the ambivalence of public debate, they also illustrate the increasing hybridity of the public sphere. Breaking political news stories, for example, may begin in embodied spaces, but once they hit Twitter or Facebook or CNN.com, they are swept up into a frenzy of digitally mediated participation, thus becoming an “internet thing.” Conversely, stories that begin online, like barbs publicly traded between elected officials on Twitter, can be picked up by traditional media outlets and reconfigured as office water-cooler chatter. And by that we mean iMessage chatter or email chatter between colleagues sitting across the room from each other. In short, whatever tenuous boundaries exist between “online” and “offline” are obliterated in the context of public debate, where digital participation is integrated into embodied experiences, and embodied experiences are integrated into digital mediation.

Conflict and unity

For many, the idea that “unity” within the public sphere is an evil twin of anything might seem like a stretch, particularly in the context of unitary democracy: people coming together to find consensus on important issues. Political theorist Jane Mansbridge (1983) expands on this ideal, noting that unitary democratic systems value common ground, equal respect, and the trust and sacrifice inherent to friendship. When disagreement does emerge, such systems rely on what classicist Danielle Allen describes as “the instruments of agreeability” (2004, 118) in the quest for peaceful consensus.

On the surface, that all sounds lovely. But even the most unitary democratic system can go either way. Because however inclusive it might appear, ingroup unity can come at the cost of ignoring, disregarding, or actively silencing dissenting – and particularly dissenting outsider – perspectives. To this point, political philosopher Chantal Mouffe (2005) asserts that consensus, regardless of its warm and fuzzy connotations, can be just another name for hegemony. Critical theorist Nancy Fraser likewise argues that “deliberation can serve as a mask for domination” (1993, 119). Conflict and unity, in other words, are far from diametrically opposed; even when the goals are unitary for some, behavior in the service of that unity can easily veer toward the antagonization of others.

This overlap played out during the 2016 US Presidential election, particularly through the campaign of Republican nominee Donald Trump. At various points in his campaign, Trump asserted that the US should ban all Muslim immigrants from crossing American borders; pledged to build an enormous wall on the US–Mexico border (that he insisted he'd make Mexico pay for); connected Mexican immigrants with criminality, murder, and rape (“And some, I assume, are good people,” he stated in a 2015 speech announcing his candidacy, with the qualification “I assume” seeming to imply that, if there are any good Mexican immigrants out there, Trump has never personally encountered any); promised to strongly police African American communities, which he continuously – and erroneously – equated with his own cartoonish hellscape vision of crime-ridden “inner cities”; warned his followers about the “international bankers” (a longstanding dog whistle for anti-Semitic sentiment) allegedly controlling the US economy; and upon suggesting that the election was rigged, urged his supporters to descend on polling places to “keep an eye” on “other communities.” Alongside these and other equally egregious assertions, Trump has repeatedly invoked the nationalist, and ultimately racist, proclamation that he, and he alone, can “make America great again.” In so doing, Trump has unified his overwhelmingly white working-class supporters around a cause – a xenophobic, racist, and fear-based cause, but a resonant cause nonetheless. The same holds for Trump's overall political platform, which rejects “political correctness” and affirms the economic struggle of many of his supporters, who feel abandoned by their government and alienated by the increasingly diverse culture that surrounds them.

By establishing common ground between himself and his supporters, by vowing to sacrifice his own needs to help fight for others, and by making supporters feel understood and fundamentally worthy – all goals of unitary democracy – Trump has created a strong sense of us. He has also created an even stronger sense of them. For those outside Trump's us, the implication that all those who qualify as them deserve less protection, less respect, and fewer (or even no) basic human rights most certainly does not create a sense of unity. It creates a sense of disconnect, conflict, and, for many, outright fear.

Just as unity can be a mixed bag, conflict is similarly ambivalent. While the conflict Trump courts is premised on a silencing denigration, many progressive political theorists advocate, and even outright celebrate, conflict premised on equal clash. Mouffe (2005), for example, is a staunch proponent of agonistic debate, which she frames as healthy, productive conflict between adversaries (as opposed to explicitly antagonistic conflict between enemies). Similarly, communication scholar Karen Tracy (2010) advocates for what she calls reasonable hostility in public debate, a framing that also embraces the adversarial register in conflicts between oppositional counterpublics. As with Mouffe, Tracy's adversarialism is not carte blanche antagonism; she says that for such hostilities to be “reasonable,” they have to respond to rather than initiate injustice or threat, push back against an action or event without devolving into unrelated personal insults, and remain sensitive to the socially rooted contextual standards of judgment surrounding the debate.

Khizr Khan's 2016 Democratic National Convention address provides an example. Khan, a Muslim immigrant from Pakistan, spoke of his son Humayun Khan, a US soldier who died in the line of duty in 2004. Noting his son's sacrifice and bravery while enlisted, Khan asserted: “If it was up to Donald Trump, he never would have been in America.” Khan then pivoted to Trump's draconian foreign policy platform, stating “He vows to build walls, and ban us from this country.” With that, Khan pulled out a pocket copy of the constitution. “Have you ever been to Arlington Cemetery? You will see all faiths, genders, and ethnicities. You have sacrificed nothing. And no one.”13 This statement was met by thunderous cheers from the audience, and resonated strongly with mediated viewers as well; almost immediately, the hashtag #KhizrKhan began trending, and the text and video of Khan's speech was shared tens of thousands of times across multiple social media platforms.

Embodying Tracy's reasonable hostility, Khan eviscerated Trump, yet he did so fairly, accurately, and without stripping Trump of his humanity. He simply reminded the audience of what Trump has actually said and done. His speech also illustrates the fact that agonistic debate and reasonable hostility can be especially powerful tools when employed by members of historically underrepresented populations. Not only do they empower individuals to speak truth to power, they affirm these individuals' perspectives and experiences, in the process holding dominant institutions and individuals accountable for unjust action. All suggesting that, for certain voices to be heard, conversations might sometimes need to get a little heated.

Just like unity, conflict is far from ethically straightforward. Both categories are, instead, fundamentally ambivalent. As a result, ethical assessment of circumstances resulting in conflict and unity (and this is often an and, rather than an or) depends on who is participating, what participants hope to achieve, and, most significantly, who stands to be empowered and who stands to be silenced as a result. There are simply too many variables to easily demarcate or universally characterize these equally, evilly, disorienting twins.

Affect and rationality

Like the evil twins of conflict and unity, affect and rationality are complementary, contradictory, and highly ambivalent, both separately and together. Each serves as the basis for productive public debate as well as the roadblock to that debate, and each collapses into and complicates the other, right from the outset. This, again, is not the traditional story, particularly in the West. Since the Enlightenment, sentimentality and emotion have often been cleaved from the thinking, reasoning mind, which is typically privileged over the feeling heart. It is only through cool, calm calculation that one arrives at the correct answer; excessive sentiment is a rhetorical liability. From this view, geek-chic celebrities shouldn't go around swearing on Tumblr, but instead should articulate their perspectives dispassionately, like a true person of science. Rationality, in short, is the means by which Mill's ([1859] 2009) “disinterested bystander” can parse the truth from all the rancor.

A fine theory, in theory, but less so when put into practice. Because instead of being a distraction from or encumbrance to productive public participation, affect is often a driving force behind that participation. Mouffe (2005) affirms this position, foregrounding the persistent centrality of passion in politics. Likewise, communication scholar Peter Dahlgren (2013) defends the value of the emotional register in public discussions. He argues that people need to be informed, and need to weigh their options deliberatively, but they also need to feel emotionally invested and “sufficiently empowered to make a difference” (76). Zizi Papacharissi (2015) further dismantles any clear demarcation between affect and political argumentation, noting that cognition is a significant aspect of emotional experience, and that emotional experience influences critical thinking.

Emotional experience is, in fact, precisely what compelled Khizr Khan to deliver such a powerful speech – and master-class rhetorical check – at the 2016 Democratic National Convention. Not just to pay tribute to his son's sacrifice, although he did that beautifully, but to directly address his adversary by name. And to his face, on national television, dismantle Trump's assertion that the country would be less safe if there were more Muslims within its borders. Our country is more safe because of my son, Khan countered, what have you ever done? – a point he delivered not calmly, not dispassionately, but as a fully invested and, frankly, pissed-off bystander. In the process, Khan was able to give voice not just to his own disgust, but to all Muslim Americans – to all Americans more broadly – similarly disgusted by Trump's racist statements. A tepid speech reminding Americans that they could vote for Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in November if they wanted to, presented without personal comment, presented in the tone of a robot, would not have galvanized the audience as it did. It would not have happened to begin with, if something hadn't first been galvanized in Khan.

Similar passion – and similar pain – underscores the organization Mothers of the Movement, and the related Black Lives Matter movement. This group, which was also given a prime-time slot at the Democratic National Convention, is comprised of the mothers of young men and women of color killed by police officers (and in one instance, a citizen vigilante). The purpose of the group is to work with law enforcement agencies and members of the black community to proactively combat the statistical reality that black people in the US are much more likely to be killed by police than are their white peers (see Lopez 2016).

On stage, these seven women spoke about coping with the loss of their children Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Jordan Davis, Mike Brown, Hadiya Pendleton, Dontré Hamilton, and Sandra Bland. They also spoke of a galvanization similar to Khan's – one that prompted the spontaneous eruption of the phrase “Black lives matter! Black lives matter!” throughout the convention hall (Kaleem 2016). It was their sadness and frustration, the mothers explained, translated into political action, that is helping them work to ensure that there will be fewer mothers like them in the future. Similarly, it is sadness and frustration, translated into political action, that spurs all participants across all media in the broader Black Lives Matter movement. Without deep, personal investment in a given issue, people are less likely to engage with underlying cultural issues and inequities. And they are much less likely to make arguments.

But, of course, not all arguments are created equal, and neither is all affect. Trump exemplifies the failings of both: bad arguments coupled with excessively affective behavior. Not only does he express nationalistic, racist, and xenophobic sentiments, he is also virulently sexist. In one well-publicized instance, he berated Fox News contributor Megyn Kelly after she asked him about his sexist discourse (including his well-publicized tendency to attack women he dislikes with gendered slurs); instead of answering her question, he called her a “bimbo” and later accused her of having “blood coming out of her wherever” (Easton 2015).

And then, in October 2016, came the kicker: a 2005 audio tape released that month captured Trump bragging to Access Hollywood reporter Billy Bush (cousin of former US President George W. Bush) about kissing women and “grabbing them by the pussy” without waiting for consent – because he was a star, and could do whatever he wanted to them (“Transcript …women” 2016). Following the surprise release of these tapes – which describe behaviors that meet the legal criteria of sexual assault – a number of women came forward accusing Trump of precisely what he and Billy Bush had chuckled so heartily over. Trump responded to the accusation that he was, in fact, a man of his word by threatening to sue his accusers, as well as the New York Times for running several of the women's stories. In an open letter, the Times' general counsel responded, in turn, by arguing that Trump's reputation has been so damaged for so many decades by Trump's own behavior that he could not possibly be libeled by anyone (Rappeport 2016b). Trump underscored this point when he mocked an accuser's appearance during a post-scandal campaign rally. “Believe me, she wouldn't be my first choice,” he said, suggesting that she wasn't attractive enough to assault (DelReal 2016) – a statement that also implicitly suggested that he has standards for the kinds of women he would be willing to assault.

As illustrated by his hyper-affective, hyper-defensive response to the growing litany of sexual assault allegations, Trump flings insults in every possible direction whenever he is challenged. Following Khizr Khan's speech, for example, Trump directed his ire at Khizr's wife Ghazala, who stood by her husband on stage during his speech (BBC News 2016). “If you look at his wife, she was standing there,” Trump said during an interview; “She had nothing to say …Maybe she wasn't allowed to have anything to say. You tell me.” The remark – a not-so-subtle jab at the supposed sexism of the Khans' Muslim faith – was insult as usual for Trump, who deflected Khizr Khan's critiques by once again trotting out anti-Muslim prejudice, editorializing by proxy through a suggestive “You tell me.” In response, Ghazala Khan told the press that “When I was standing there, all of America felt my pain, without a single word. I don't know how he missed that.”

In another memorable instance during a March 3, 2016, Republican Presidential primary debate, Trump responded to fellow candidate and Florida Senator Marco Rubio's suggestion that his hands are small with an assurance to the American people that his penis size was more than adequate. “I guarantee you there's no problem,” he barked. “I guarantee you” (Krieg 2016). These embodied behaviors are reflective of Trump's online persona as well; when mediated through his Twitter account (which as of this writing boasts 12.7 million followers), Trump is what Politico writer Joe Keohane (2016) describes as a “cry-bully,” someone who is equally insensitive and sensitive, aggressive and easily wounded – expressed through incessant boasting, the assertion that his detractors are sad and disgusting, and a broken record of “crowing, cajoling, whining and threatening.”

Sharpening this picture, Zachary Crockett (2016) of Vox analyzed seven months of Trump's tweets, and posited that 45 percent contained explicitly negative sentiment, mostly expressed through insults. By Crockett's count, Trump's two most frequently used negative words were “bad” and “sad,” trailed closely behind by “weak,” “little,” “dumb,” “horrible,” “nasty,” and “unfair.” These insults, as Rolling Stone's Tessa Stuart (2016) explains, follow a few basic trajectories: that the target doesn't have “it,” that they're a dog, that they're a failure, that they have no credibility, that they are the worst, and that they've asked him for favors before. By the standards of reasonable hostility, over-the-top affect precludes Trump from engaging in meaningful public debate; he's too busy huffing and puffing and, in an ironic twist, accusing others of being sad and disgusting.

But judging affect based solely on Trump would be as incomplete as judging the US based solely on Trump (please don't). Passion – and the spectrum of emotions it subsumes, from profound pain to profound love to profound anger to the profound sense that things could be better, that things should be better – is critical to every social movement and every meaningful conversation. It's also a potential hindrance to every social movement and every meaningful conversation. Just like unity and its evil twin conflict, each can be used as a weapon, and each can be harnessed in the service of social justice. And in the process, each highlights the fact that these binaries aren't binaries at all. They are different sides of the same coin, as they always have been.

Make America pretty much the same again

As Trump's Presidential candidacy attests, the contemporary public sphere is a brave new world of digitally mediated vernacular participation. However, public debate also exhibits many continuities across eras and media, particularly around the evil twins of conflict and unity and affect and rationality. These evil twins were just as inextricable then as they are now – and just as confounding to each generation of cultural theorists who looked around, furrowed their brows, and wondered just what in the hell the world was coming to.

Conflict and unity, same as it ever was

The fact that unity within a collective or around a perspective can simultaneously breed deep conflict has persisted for generations. This point is evidenced by the countless jousts, scuffles, slap fights, bar brawls, and various stripes of honorific duels that have long peppered public debate – and which have subsequently resulted in some people cheering and giving each other high fives, and other people slinking back home to nurse their wounds.

In the US, few of these partisan altercations are as symbolically significant as the 1856 caning of Charles Sumner. This event preceded the American Civil War by five years and presaged the level of rancor that would consume both Northern and Southern factions. Sumner, an abolitionist Massachusetts Senator, had just given an impassioned speech denouncing the recently passed pro-slavery Kansas–Nebraska Act. He criticized the political power of slave owners, including the authors of the Act, one of whom was Senator Andrew Butler of South Carolina. In addition to attacking his role in the creation of the Act, Sumner insinuated that Butler was having sex with his slaves, and according to Senate historian Richard A. Baker, denounced him as a “noise-some, squat, and nameless animal …not a proper model for an American senator” (2006, 61). Butler's distant cousin, South Carolina Representative Preston Brooks, was incensed. Believing that Sumner wasn't a gentleman and therefore didn't deserve to be challenged to a duel, he decided to mete out the kind of punishment he would reserve for a dog (his words, not ours; everything about that is awful). So two days after Sumner's speech, Brooks and several supporters stormed into the Senate chamber and beat Sumner to the brink of death with a cane; according to historian James M. McPherson (2003), this attack consisted of at least 30 lashes directly to the head. Bleeding profusely, Sumner had to be carried away. Brooks strutted right out of the Senate chamber, as onlookers were simply too stunned to try and detain him.

This story is significant not just because the attack was carried out by an elected official on the Senate floor, and not just because of the physical and mental pain Sumner suffered as a result. It is also significant because Brooks wasn't just not ostracized for his behavior, he was embraced as a Southern hero. Newspapers in South Carolina printed gushing editorials supporting Brooks' “noble” defense of his home state, and Virginia's Richmond Enquirer exclaimed that the caning was “good in conception, better in execution, and best of all in consequence. The vulgar Abolitionists in the Senate are getting above themselves …They have grown saucy, and dare to be impudent to gentlemen!” (quoted in McPherson, 151). According to Brooks, his genteel Southern compatriots even begged for fragments of his cane to use as “sacred relics.” After winning reelection in South Carolina – he initially chose to resign facing censure, but his constituents would hear nothing of it – Brooks was sent hundreds of new canes, some inscribed with messages like “Hit Him Again” and “Use Knock-Down Arguments.”

Like Brooks' bombastic, sectarian violence, Trump's various identity performances online and off – particularly those foregrounding his blustering racism, sexism, xenophobia, and “screw you I'll say what I want” attitude toward detractors – have inspired ingroup unity by way of outgroup hostility. Trump has proven to be a particularly unifying force for the Ku Klux Klan, splinter white nationalist groups, and the cacophony of reactionists, antagonists, and neo-supremacists that have come to be known as the alt-right, all of whom have declared, publicly and enthusiastically, their support for a candidate who “gets it.”

To be fair, aligning his performative mask to such audiences hasn't always been comfortable for Trump; throughout the campaign, he tried, sometimes more and sometimes less successfully, to publicly distance himself from these groups and their support.14 But he has also thrown these groups plenty of bones that have helped strengthen their particular and very limited sense of us – for example, by retweeting messages from Twitter users with white nationalist ties, even ones with explicitly white nationalist handles. And, in one especially infamous case, by tweeting an anti-Semitic image of Hillary Clinton superimposed with the Star of David, originally posted to a white nationalist website. The sense of unity engendered by Trump's racist expression runs deep, and is deeply ambivalent; when Clinton denounced these and other bigoted actions in an August 2016 speech connecting Trump with white nationalism generally and the alt-right specifically, alt-right boosters were, as the New York Times' Alan Rappeport (2016a) reported, “thrilled.” By making that connection, they argued, she had given their movement greater visibility – and, in turn, greater legitimacy – than it had ever enjoyed.

Trump's actions in the above instances (really, throughout his whole campaign) speak to concerns often attributed to the contemporary historical moment, but which in fact persist across generations. Arguably, the most pressing of these concerns center on when, if, and how observers should intervene when debate gets a little too contentious, and at what point adversarial clash becomes a threat to the common good. These questions are particularly pressing when considering counterpublic pushback against dominant marginalization. However forceful their messages might be, however uncomfortable these messages might make some citizens, voices of historically marginalized groups should be heard; these voices are necessary to the overall health of a democracy. The systemic injustices raised by the Black Lives Matter movement (and the Civil Rights movement decades before that) clearly fall into this camp. Even if – even when – the discussions get not just a little, but a lot heated.

That said – and this is where problems creep in – just because a group is in conflict with the mainstream doesn't make that group good. The mainstream might have its problems, but not to such an extent that it warrants “the enemy of my enemy is my friend” transitive logic. Explicit white nationalism, for example, whether expressed through embodied action or digital participation, most certainly runs counter to mainstream sensibilities, and thankfully so. In that sense, white nationalists are marginalized; hence their delight at being regarded, suddenly, as sufficiently influential to be vocally condemned by one US Presidential nominee and implicitly embraced by another.

But regardless of the relative marginalization of white nationalists and the alt-right, questions about how best to respond, or if to respond, to antagonistic conflict remain as vexing now as they were back when Preston Brooks nearly murdered Charles Sumner. On many digitally mediated platforms, these questions are especially complex, as the oversight of public debate is often in the hands of private businesses, not government entities. Until and unless online behavior breaks existing laws, platforms must decide if and how to respond to users' antagonistic speech. Often, those decisions are tethered more to bad press than to legal (or even broadly ethical) concerns. Reddit, for example, has faced considerable backlash over the years for hosting content that might not be explicitly unlawful, but certainly skirts the line between protected speech and speech that is, to be very generous, problematic (Massanari 2015). Twitter has also uncomfortably walked this line, and in response to high-profile cases, including the harassment of Leslie Jones, has been forced to revise existing on-site moderation policies (Warzel 2016). Because they are reacting to particular controversies, these changes are often undertaken swiftly, without much time for users to respond, or even to realize that the changes have been implemented.

Amplifying this confusion is the fact that moderation policies can vary widely between platforms, as each platform is guided by a different and ever-evolving outlook on speech protections and general sense of responsibility for enforcing these protections. With so few consistently reliable reporting options, it's unclear how individual Twitter users should respond to instances of personal abuse, let alone abuse lobbed against others – for example, the alt-right's harassment of Leslie Jones, or its systematic, even gleeful, opposition to Black Lives Matter. Should antagonistic posters be named and shamed? Counter-antagonized? Should their impact be minimized, so the broader public can't see offending posts? Should their impact be maximized in order to call the greatest amount of attention to bad behavior? Should the most offensive contributors be reported and reported and reported until they're finally, maybe, banned?

The prospect of silencing conflict, regardless of circumstance, regardless of severity, might cause some to bristle. Indeed, for many scholars, censorship is itself an offensive proposition. Mill ([1859] 2009) famously falls into this camp. In his foundational “On Liberty,” he argues that the silencing of equal clash “is an assumption of infallibility” (21), and asserts that censorship creates a “mental slavery” that chokes out an “intellectually active people” (36). According to Mill, it's not the violent conflict between parts of the truth that is the formidable evil. It is, rather, suppression of half the truth. Mill thus comes down on the side of more clash, not less; louder speech, not selective muting. This is not to say that Mill, or other free speech advocates, are necessarily apologists for antagonism. A nuanced version of the “more clash, not less” position – which acknowledges that nasty speech is, indeed, quite nasty – is best summarized by the early twentieth-century British writer Evelyn Beatrice Hall (1906), who asserted that “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” (1906, 199).15

On paper, such positions seem to represent a noble compromise, one underscoring vibrant democracy. It's the loss of precisely this idealized vibrancy – one predicated on ever more and ever louder clash – that many alt-right advocates mourn when their Twitter accounts or subreddits are banned, or simply when their comments are deleted from a particular thread. Regardless of who is making the argument (or how earnest they might be, as members of the alt-right often trot out democratic ideals to justify their presumably unalienable right to attack others, and others' presumably unalienable obligation to tolerate their abuse), blanket assertions that more speech is the best response to bad speech often overlook differential power relations, and falsely presume that being heard is merely a function of speaking up and adding your voice to the clash. Of course this is possible for some, particularly those already in positions of privilege and power. But others could spend their lives screaming and never be heard. Not through lack of trying, as proponents of the “more clash, not less” position implicitly suggest, but through lack of access to a prominent platform, and, most importantly, an audience willing to listen.

That said, and even when they overlook issues of power and access, the most vocal supporters of the “more clash, not less” position are often willing to place some limits on unfettered speech. This is particularly true when speech is premised on the foundational belief that some people shouldn't be part of the debate, and perhaps shouldn't be allowed to live. For Mouffe (2005), violently extremist, regressive perspectives merit silencing because they undermine conflictual consensus. She argues that democracies need agreed-upon values – “all people are created equal,” for instance, or “all people are entitled life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness” – before productive, agonistic conflict is even possible. Therefore it's appropriate, and in fact is necessary, to draw a line between those who reject the basic ground rules and those who work within them. If you fail to play by the rules, in other words, you forfeit your right to step on the field.

Mill, open clash advocate that he is, takes a similar position, arguing that public debate premised on “want of candour, or malignity, bigotry, or intolerance of feeling” ([1859] 2009, 55) isn't within the rules of the game. This is speech that silences, and therefore may justifiably be silenced. The question is, at what point is something objectively silencing, as opposed to “merely” infuriating? There is no question that much of what the alt-right posts online, for example (to say nothing of what Trump regularly says on Twitter and during rallies), is premised on want of candor, as well as malignity, bigotry, and intolerance of feeling. But is it wanting of candor enough? Malignant, bigoted, and intolerant enough? Who gets to make that determination, and how might that person's lived experiences influence their ability to parse outright silencing practices – which render a person physically unable or psychologically unwilling to speak – from other affective or argumentative responses?

Further complicating this picture, what if the same behavior silences some audience members, but spurs someone like Khizr Khan to face his antagonist on a national stage and call him, essentially, a blustering, un-American coward? The same could be said about divergent reactions to Trump's gleeful, chest-thumping boastings about sexual assault. Even if these statements were, as Trump later insisted, “just locker room banter,” some women – and not just his (many) accusers – may have felt silenced, violated by proxy. But some were empowered to push back against Trump and the toxic masculinity he embodies. This is where the seemingly intuitive rhetorical baseline between silencing / not silencing breaks down, a sudden clatter amplified by our second set of evil twins: affect and rationality.

Affect and rationality, same as it ever was

In each case described in this chapter – in fact, in all instances of contentious public debate – conflict and unity are tightly coiled with affect and rationality, and are both equally essential to clash and commiseration. This connection functions like clockwork, regardless of who is participating in what debate, under what circumstances, in what decade – or even century. In the process, the overlap between conflict, unity, affect, and rationality further dismantles not just the demarcation between each set of evil twins, but also any clear demarcation between each individual concept.

To illustrate this continuity, we turn again to Trump, specifically his notorious Twitter antagonisms. Trump's targets (restricting ourselves solely to elected officials from the state of Massachusetts; we only have so much space) include Senator Barney Frank (in a December 21, 2011, tweet: “Barney Frank looked disgusting – nipples protruding – in his blue shirt before Congress. Very very disrespectful”), former Governor and 2012 Presidential candidate Mitt Romney (in a February 25, 2016, tweet: “Mitt Romney, who was one of the dumbest and worst candidates in the history of Republican politics, is now pushing me on tax returns. Dope!”), and Senator and person of Native American heritage Elizabeth Warren (in a May 6, 2016, tweet: “Goofy Elizabeth Warren, Hillary Clinton's flunky, has a career that is totally based on a lie. She is not Native American”).

Even if Trump's adversarialism seems to have taken affect to new heights (or new depths), the 2016 election is certainly not the first characterized by name-calling and mudslinging. For example – and this is just one example among many in US history – the 1800 Presidential election, which pitted sitting President John Adams against sitting Vice President Thomas Jefferson, would have done Trump proud. Or at least, prompted him to shout variations of the words “Sad!” and “Failure!” while vowing to make the new republic great again. As historian Kerwin Swint (2006, 2008) chronicles in his countdown of the 25 dirtiest US campaigns of all time, the 1800 election featured personal attacks mocking candidates' religious views, intelligence, sexual appetites, and even their gender identities. Candidates were also referred to in the press with a variety of increasingly creative slurs; for instance, a Federalist handbill wrote that Jefferson was, in addition to not being white enough, “raised wholly on hoe-cake made of coarse ground Southern corn, bacon and hominy, with an occasional change of fricasseed bullfrog” (2006, 183). Trump might take the name-calling to the 21st-century extreme, but he certainly didn't invent foaming-at-the-mouth affection.

Nor is he the first to inspire concerns about these sorts of behaviors. Beyond worries about the “dirtiness” of professional politics (an old adage indeed), the fear that people are too irrational, too mean, and conversely too sensitive to accomplish anything positive, has long haunted political theory. Mill ([1859] 2009) encountered enough nastiness in nineteenth-century public discourse to comment on it; Mansbridge (1983) uncovered drama, fighting, bullying, domination, outbursts, and people afraid to speak up for fear of reprisal or judgment in the midst of idyllic, tight-knit 1970s town hall meetings; and Tracy developed her theory of reasonable hostility by looking at the “emotionally marked, critical commentary” (2010, 203) prevalent during 1990s school board meetings.

Of course, some of this is confirmation bias; empirical research conducted by Papacharissi (2004), Carlos Ruiz et al. (2011), and Dimitra Milioni (2009), all exploring a variety of mediated environments, suggests that audiences tend to overstate the inflammatory dimensions of public debate. Not everyone debating public issues, online or off, is Wil Wheaton screaming at UK Science Minister Jo Johnson. That said, as evidenced by generations of theorists' handwringing, the vocal, contentious minority is especially visible, and therefore especially concerning – and is, presumably, why so many cultural problems remain unresolved.

Again, maybe this is true in theory. But in practice, things aren't so simple. Khizr Khan's disgusted takedown of Trump's racism, Black Lives Matter activists' passionate pushback against systemic injustice, and incensed reactions to a US Presidential candidate bragging about sexually assaulting women, all show that pointed – even impolite – responses to systemic antagonism can absolutely serve public ends. Of course, it would be better if all those systemic antagonisms were already resolved. And it would certainly be better if marginalized groups didn't bear a disproportionate burden in continuing to combat the antagonisms and violence that disproportionately affect them. But until justice is equally just for everyone, the discomfort resulting from heated exchanges reminds us all that there is still more work – much more work – that needs to be done.

Affect isn't just passion or anger, of course. Affect covers the full range of human emotional experience – play and playfulness very much included. And, just as anger and frustration can facilitate meaningful public debate, so too can engagement that appears to be “just” playful. Theorists across disciplines have long affirmed the political potential of play, immediately complicating the notion that play is, or should be, framed as “just” anything. Game theorist Miguel Sicart, for example, argues that play is “a critical liberating force that can be used to explore the ultimate possibility of human freedom” (2014, 72), making it the perfect conduit for political expression. Political scientist Marcus Schulzke (2012) likewise asserts that playful audience engagement with satirical political programs like The Colbert Report promotes civic awareness. And Papacharissi suggests that playfulness can be a “strategy for dealing with the fixity of norms” (2015, 95) that often constrict public debate, thus helping connect individual creativity to collective expression.

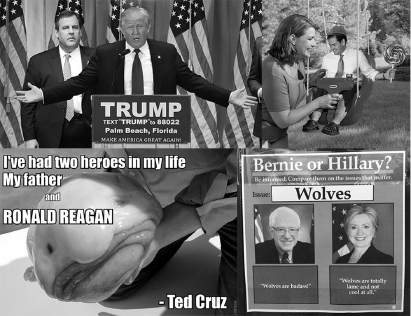

Digitally mediated play with the 2016 US Presidential election certainly demonstrated such a connection. Evidencing this affective participation, Figure 7 collects images inspired by a few memetic moments during the 2016 primary elections. First, when New Jersey Governor Chris Christie dropped out of the Presidential race after many deeply contentious clashes with Trump, then endorsed his former rival, then was insulted by Trump on a hot mic, and then still stood behind him – visibly stupefied – during a victory speech, citizens embraced the opportunity to play. As Trump spoke, Christie blinking vacantly beside him, participants across social media platforms wove satirical tales about Christie being held hostage by his future overlord. A #FreeChrisChristie hashtag emerged, allowing Twitter users to express mock concern. Commenters implored the governor to blink in Morse code if he was in distress, wondered if he was regretting every decision in his life that had led him to that moment, speculated that he was maybe just dreaming about the pho he wanted for dinner, and photoshopped the pair as a master/slave couple in BDSM latex. Digg compiled looping Vine videos that zoomed in on Christie's face while emotive music – from a slasher horror soundtrack to the bumbling horn-driven theme of HBO's Curb Your Enthusiasm to the sullen, existential opening lines of Simon and Garfunkel's “The Sound of Silence” – played over the governor's blank expression (Cosco 2016).

Fellow Republican Presidential candidate Ted Cruz also found himself on the receiving end of ample memetic play. Not only was he – for no discernable reason other than the fact that people didn't like him – widely purported to be the Zodiac serial killer from the 1970s, he was also compared to a white, slimy blobfish. Images of such fish were captioned with quotes from Cruz' various stump speeches. Similarly, after Trump called Republican candidate Marco Rubio “Little Marco” during a televised primary debate, participants scouring Google images for meme fodder stumbled upon an image – taken the previous August in a furniture store – of Rubio sitting in a comically oversized chair, his face beaming with childlike glee. Merciless photoshops, unsurprisingly, followed. Finally, while still vying for the Democratic Presidential nomination, Clinton's perceived out-of-touch persona was mocked in a series of annotated images that cast her as painfully inauthentic compared to Democratic rival Bernie Sander's inescapable, effortless cool.

The affect evidenced by “Ted Cruz Blobfish,” “Little Marco,” and “Cool Bernie” images, along with all the other playful – if ideologically ambiguous – engagement with the 2016 election, might seem to oppose, or at least hinder, more “serious” political participation. But just because something is silly doesn't mean it can't also forward a serious message – maybe not for the image creator, but for any of the tens or hundreds of thousands, even millions, of audience members who subsequently remix, retweet, or simply save the image to their hard drives for later. And maybe not out of a sense of play; maybe because they feel angry or confused or even frightened (we truly do apologize for that Ted Cruz blobfish). The specific affective response is almost irrelevant. What matters, and what connects all this affective participation of the present with the affective participation of the past, is the fact that people care, for whatever reason, and as a result feel compelled to do or say something in response. This is how all public debate unfolds. Not in opposition to affect, and not in opposition to conflict. As a basic function of them, just as public debate is also a basic function of unity and rationality. Not taken separately. Not taken as a binary. But taken, instead, as an ambivalent tangle. Same as it ever was.

Trumping the play frame

The previous section illustrated the significant through line between public discourse past and present. It established this connection, in part, via a discussion of Donald Trump of all people, who is often framed as nothing the American electorate has ever seen before. In this section, we will take the somewhat conflicting and somewhat complementary stance that, while there is precedent for the behaviors exhibited by Trump, and precedent for public pushback against Trump, the tools that facilitate this expression and pushback are new, unwieldy, and profoundly ambivalent. That ambivalence – ushered in by reduced social risk, the communication imperative, and Poe's Law – changes the conversation, changes the stakes, and changes how we can and should talk about what to do about all these changes.

The double-edged sword of affective attunement

People have long debated the social and cultural issues that matter to them, whether to express support or lob criticism. But the reduced social risk of digitally mediated spaces allows more people to speak more freely about sensitive subjects than would be safe, or even logistically possible, in embodied contexts. Equally integral to this discourse, and setting it further apart from embodied interactions, is the communication imperative. People are, of course, free to express all kinds of affinity in embodied spaces. But unlike embodied affinity – which, as discussed in Chapter 2, may come with bodily or professional risks (or more basically than that, simply be inconvenient) – the process of expressing affiliation online can be as easy as clicking the Like button.

When publics lend their voices to resonant causes, they evidence what Papacharissi (2015) describes as “affective attunement.” This attunement facilitates collective unity by connecting counterpublic participants to like-minded others, emboldening them in the process. In response to the harassment directed at Leslie Jones, for example, friends and sympathetic onlookers used the hashtag #LoveforLeslieJ to express support for Jones and try to counterbalance some of her abusers' hatefulness. That said, just as supporters could search for and use this hashtag, so too could Jones' abusers, revealing the flipside of affective attunement; the same affordances of reduced social risk and the communication imperative that engender support can also connect those bent on silencing and antagonizing.

It's not just that people have more opportunities – for better and for worse – to participate in public debate online. They also have the opportunity to directly address those implicated in, impacted by, or precipitating that debate. Whether the person in question is a traditionally public figure or an everyday citizen swept up into an unfolding controversy, the affordances of digital media facilitate a whole lot of talking back. This talk was possible in the pre-internet era, to be sure; letter writing campaigns existed before the internet, as did telephone calls placed to politicians' beleaguered office assistants. But digital media lend unprecedented immediacy, public visibility, and at times outright ferocity to familiar ambivalence. Evidencing this unprecedented influence in the context of the 2016 US Presidential election, Wired reporter Issie Lapowsky (2015b) notes that “It's no longer just up to the campaigns to steer the conversation and their opponents to counter it. Now we can all play a role in spinning the new narrative, which dramatically changes the power structure in campaigns.”

And not just in campaigns; legislative action is also subject to the distributed imposition of populist commentary. When Indiana Governor and Trump's eventual Vice President Mike Pence signed a restrictive anti-abortion bill into law, for example, frustrated feminists decided to target the Governor directly with a “Periods for Pence” social media campaign (see E. Crockett 2016). In addition to calling and emailing Pence's office with explicit narrative accounts of their latest menstrual cycles (accounts they would then post publicly to their group's Facebook page, à la the Battletoads shenanigans highlighted in Chapter 3), participants posted messages about cramps, flow level, number of tampons used, and other exacting, clinical details, directly to Pence's Facebook page – the satirical rationale being that, if Pence is so concerned with his constituents' reproductive cycles, his office would want to be kept abreast of every period in the state at all times. By commandeering the news cycle through satirical interventions, participants were thus able to influence the direction of public debate surrounding the bill.

As always, this distributed commentary cuts both ways. The same basic tactic used on Pence was used in the sustained harassment of Leslie Jones. For months, when people talked about Jones, or when people talked about her Ghostbusters reboot more generally, discussions of the abuse she suffered weren't too far behind. And just as Periods for Pence participants were able to speak their truth with minimized fear of negative retribution, Jones' harassers were able to continue their campaign from the relative safety of their own Twitter feeds – a fact that ultimately prompted Twitter to address the controversy. “We know many people believe we have not done enough to curb this type of behavior on Twitter,” a spokesperson wrote; “We agree. We are continuing to invest heavily in improving our tools and enforcement systems to better allow us to identify and take faster action on abuse as it's happening and prevent repeat offenders” (Warzel 2016).

The reduced social risk that facilitated both Periods for Pence and Jones' harassment also underscores what Tim Highfield (2016) calls “shaming and callout culture.” Public shaming is in no way a new phenomenon, of course, and isn't restricted to digitally mediated spaces. However, it takes on new dimensions when any person across the globe with an internet connection and a minute or two of extra time on their hands can join the collective chorus. In embodied spaces, there are physical, logistic, and even legal limits (in terms of room capacity or the need for demonstration permits) to how large a crowd can grow, how quickly. But not online. With just a few clicks of a few different buttons, participants can instantaneously identify a person or behavior that violates an established normative ideal and then, just as instantaneously, rally around that person, place, or thing, perhaps to demand an apology, perhaps to demand the person face professional consequences, perhaps simply to make their displeasure known.

Some examples of shaming and callout claim an explicitly progressive agenda, for example the Twitter account @YesYoureRacist, which retweets racist posts that contain the phrase “I'm not racist, but …” in order to call the poster out for being exactly that. But Jones was also a target of shaming and callout – though much more nefariously, what she was being shamed and called out for was being a successful black woman. One who decided that she'd had enough, and pushed back against the initial wave of harassment she received. This stance prompted alt-right apologist Milo Yiannopoulos to accuse Jones of being, as Vox's Raja Romano (2016) writes, “unable to handle criticism” – thus catalyzing a second and even more ferocious wave of harassment. Unity, once again, built atop conflict, and conflict, once again, built atop unity – but amplified in whole new ways.

Poe's Law and its (continued) complications

Whether the apparent goal is conflict or unity, whether the apparent register is affective or rational, digitally mediated debate is complicated by the difficulty – if not impossibility – of parsing the ironic from the earnest during public conversations online. This difficulty stems back to our old friend Poe's Law, which can thwart even the most earnest attempts to discern intent during collective conversations – not just what shades of affect are being communicated, but what argument a person might be trying to make through those shades, if they are arguing anything at all. In the case of Boaty McBoatface, for example, pro-Boaty participants used all the tools in their communicative toolkits to signal their displeasure with NERC, the British Crown, and democracy in general. But that doesn't mean, necessarily, that these participants actually agreed with their own stated opinion. Milner himself walked this line. While he numbered among the staunchly pro-Boaty public, he also numbered among the public who thought the story was kinda just funny, and therefore was engaging, at least in part, because it was making him and his Twitter friends laugh. Just by observing Milner's Boaty-related tweets and retweets, an outsider would have a difficult time knowing to which public – or, more appropriately, which publics – he belonged. Phillips herself was unsure, prompting her to ask Milner if he was sincerely concerned about the trampling of populist will, or if he was playing along because the whole thing was silly. “………I don't even know anymore,” he replied.

In the vast majority of cases, however, one is unable to ask whether an online participant really meant it when they said, for example, that rainbow tie-dye cakes are a stepping stone on the road to fascism, or that they “condemn the cowardly campaigns of moral subjugation and propaganda that seek to instill self-hatred and surrender within European-American youth and justify the continued invasion and degradation of the lands, institutions, and cultural heritage that is rightly ours” (“Union of White NYU Students” 2015, …eyeroll), or that they think Ted Cruz really is the Zodiac Killer. The same questions persist when assessing visual content, like images of “Little Marco” and his fun little whirlygig hat and lollipop, or images of Ted Cruz likened to literally the world's grossest fish.

Where sincerity ends and Chapter 3's play frame begins is up for grabs in an environment governed by Poe's Law. Maybe the creators and sharers and tweakers of this content were merely signaling silliness – just the play frame, and nothing more. Because a grown-ass person the state of Florida sent to the Senate is wearing a fun little whirlygig hat and holding a lollipop. Or because, come on, that blobfish resemblance is actually pretty uncanny. Then again, maybe these images spoke to something more serious, related to how those creating, sharing, and tweaking the content felt about Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz. Or maybe they were signaling a little bit of both: a serious political or cultural argument approached through the play frame.

In cases of polar research vessel names and tie-dye cakes, these stakes aren't especially high. What someone really means might be a point of curiosity, but is nothing to lose any sleep over. Cases in which a person is variously defamed, from being accused of a serious crime to being accused of being a blobfish, become more muddled. Maybe it's funny and harmless when the person accused is a politician you hate, but you would probably think it was far less funny and far less harmless if it was you some amorphous group of anonymous strangers was accusing of being, well, anything. Funny until it stops being funny; there but for the grace of the internet go you. And in cases featuring more explicitly offensive content, from extreme vulgarity to personal insults to broader identity antagonisms, what someone really means can make all the difference. Without knowing whether something is an actual bite or simply looks like a bite or is a satirical combination of both, one can't be sure if the appropriate response is to bite back, walk away, or laugh and join the conversation.

The question is, does that matter? Is “responding appropriately” a behavioral ideal for such a fractured and fracturing space? In an article co-written with Allum Bokhari, fellow contributor to the ultraconservative Breitbart blog (Bokhari and Yiannopoulos 2016), Milo Yiannopoulos argues that motives make all the difference, and should therefore determine how a person reacts to posted content. Speaking to the anti-Semitic, racist, and generally antagonistic things members of the alt-right post to social media – i.e. their malignity, bigotry, and intolerance of feeling – he and Bokhari note that “Just as the kids of the 60s shocked their parents with promiscuity, long hair and rock'n'roll, so too do the alt-right's young meme brigades shock older generations with outrageous caricatures.” But no worries, they argue. These “young meme brigades” aren't actually bigots. At least, Bokhari and Yiannopoulos assert, they're not bigots any more than “death metal devotees in the 80s were actually Satanists.” Through this framing, Bokhari and Yiannopoulos suggest that harmful expression isn't really harmful, because it isn't really real. The appropriate reaction is therefore to acknowledge the play frame, stop being so sensitive, and move along. This was precisely Yiannopoulos' critique of Leslie Jones' reaction to the initial onslaught of Twitter harassment. She took it seriously, responded publicly, and was punished accordingly, essentially for refusing to not take her harassers' racist words at face value.

Rhetorical somersaults aside (“you should know better than to take us seriously, but make sure you take us seriously because if we are actually joking in the way we say we are, you taking us seriously is, quite literally, the entire punchline of our joke, so please ignore us when we say we're just joking”), this position speaks to the complications unearthed by an environment that so thoroughly facilitates fracture and confusion. Poe's Law is simply what happens when more people, more capable of writing themselves into existence in a variety of ways, are more able to participate in more conversations through vernacular media that are more modifiable, modular, archivable, and accessible than any conversations that have come before. In the face of so much more, all participants can do is assess the content itself, and derive, or attempt to derive, conclusions about what has been communicated, not what someone might have meant to communicate.

And this, in our minds, is the appropriate response to arguments like those forwarded by Bokhari and Yiannopoulos. Online, if something appears to signal bigotry, it's bigotry. Because that is, quite literally, the message being communicated. And when only the message is the message, what the creator (original Photoshop artist, tweeter, comment poster, etc.) might really mean in their heart of hearts is moot. For one thing, meaning doesn't exist in the creator's heart; recalling our discussion of Roland Barthes (1977) in Chapter 4, the meaning of a text exists in its destinations, not in its origin. But even if meaning did live in the heart of the creator, the incessant clatter of tangled, multiplicitous, unattributed and unattributable texts would make it next to impossible to connect this meaning with that heart. We can't know for sure exactly who we're dealing with; consequently, who cares what their heart is like.

More importantly, however, we all have the right to reject someone else's play frame, to shake our heads and say “that's not funny.” Something might look like a harmless joke to the teller. But if it hurts us, regardless of what the other person might have been trying to accomplish, that's a bite. The basic idea that you don't get to tell me how I'm feeling is intuitive enough. Online, we all need to remember that that same truth holds for everyone else.

Chapter overview and looking forward

This chapter has illustrated the ambivalent overlap between the evil twins of conflict and unity, along with affect and rationality. While this intertwine of ambivalence spans public debates regardless of media, it is most conspicuous, and most conspicuously vexing, when the voices of some silence the voices of others, particularly online, when questions of whose voices these are and why they might be participating cannot be satisfactorily answered. In those cases, what can be done? What should be done? Where do we locate individual and collective responsibility? What rules should apply to whom? Who can say, for sure, who is outright rejecting the established rules and who is fighting over the correct interpretations of what the rules mean?

Our position is simple. We are staunch advocates of the democratic process and think that problematic speech should be countered through more speech. Except actually maybe not, because not all speech, and not all voices, are given equal weight, and that position privileges those whose voices already carry further and louder than others. So okay, we're staunch advocates of the democratic process and think that the only voices that should be silenced are the voices that silence others. Except actually maybe not, because sometimes those silencers are silencing silencers, and that's good, except when it isn't, and anyway even if we silence all hateful expression, that doesn't mean we eradicate it, it means we can no longer hear it. It'll just move elsewhere, to embodied spaces or spaces online that are more difficult to access. And wouldn't it be better to know what upsetting things people are saying, so at least we're not blindsided when something awful happens?

So okay, we're staunch advocates of the democratic process and think it's actually good for things to get a little heated sometimes, because that's how we know that democracy is working. Yes. Except actually maybe not, because underrepresented populations disproportionately bear that burden and are therefore framed as a kind of cultural collateral – you'll still be targeted, hope that's cool, but at least we'll know what we're up against, thanks guys. That burden is one that has been borne too long by too many of the same people. So okay, we are staunch advocates of the democratic process…as our voice trails off and we stare blankly into the distance.

Looking toward the conclusion – and the future more broadly – we don't have the definitive answer here. We have a handful of different answers, but they are all “yes but,” not “yes and.” We maintain, regardless, that we all benefit individually and collectively when there are more voices participating in a conversation. We also maintain that we are grateful to all those who have fought to include more voices in the chorus, and grateful to those who continue that fight. If history has been plagued by lack of voice and lack of representation, maybe the future will be plagued by too many and too much – and that's progress, even if also impossibly ambivalent.