There was once, so they say, a Zulu chief who sat day after day gazing sadly into the distance. Seven of his sons had gone to prove their manhood, and all had disappeared beyond the Cliffs of the Falling Goats where cannibals lived. Only the youngest boy was left – but though he was strong and seemed clever, he could not talk. No-one had ever heard him speak.

Old Mbata, the wisest Induna, who had advised his Chief for years, wondered how to bring happiness back to him. He watched and waited and listened. Then one day he approached the grieving Chief and said to him, ‘Nkosi, Lord, your youngest son has been trying to tell me something. Early in the mornings, he has pulled at my arm and pointed out towards the mountains where his brothers went. But each time my old legs moved too slowly and by the time I had arrived, there was nothing to see. But today I saw what had excited him: seven birds perched on the fence of the cattle kraal’.

‘What is so strange about birds?’ asked the Chief.

‘These birds were like none other,’ Mbata explained. ‘They were bright green with waving plumes. They seemed unafraid when the boy was near, but they flew away when I came nearer. Then they circled around my head before they flew off towards the Cliffs of the Falling Goats. It would seem to me that they are magic birds.’

The Chief’s eyes brightened. ‘Have they come to comfort me for the loss of my sons? If that should be so, then I will reward you with seven of my fattest cattle. These magic birds must be caught. Send seven boys after them at dawn tomorrow. They will surely catch them.’

So the boys were chosen and the Chief’s youngest son showed, by signs, that he insisted on being one of the seven. Though Mbata was worried to risk the life of the Chief’s one remaining son, he knew too that the boy had to prove his own bravery for himself. Like his brothers, he had to prove his manhood.

‘Go and find these birds,’ ordered the Chief. ‘Do not let me see your faces again until you return with them. Here are assegais for you to take with you.’ And to his son he gave a special assegai of his own.

Sure enough, next morning the strange green birds appeared again. The Chief watched, with Mbata at his side, as the seven boys followed the seven birds across the veld and out of sight.

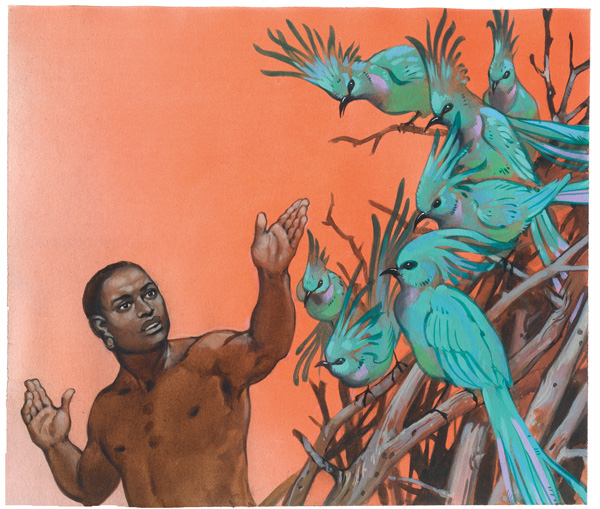

The beautiful birds led them far into the wild bush country, past the Cliffs of the Falling Goats and over a great river. There the boys stopped to gather twigs and rushes to make cages for the birds they hoped to catch. The next morning, the birds led them up the steep, forested mountains on the farther bank. By the third evening, the birds beat their green wings more slowly. They were tired. The Chief’s son crept ahead of the other boys and made his way silently towards one of the birds which had perched on a thorn bush. Triumphantly, he sprang forward and grabbed the long shining tail feathers just as the poor, exhausted bird tried to flutter out of his reach.

Following his example, each of the other boys stalked and caught a bird for himself. When they gathered together beside the cages, they were all chattering with excitement.

‘At last, at last!’ shouted the Chief’s son joyfully. And suddenly the other boys realised that the boy had found the power to speak.

They rejoiced greatly with him and they gave him a new name – for that is the Zulu way – calling him Kulume, which means ‘speak.’

‘Our task is won!’ he cried, happily. ‘Tomorrow we can take our birds and my new voice back to my father. Let us start back towards home at once.’

They hurried down the mountain slopes but soon it was night and they did not know where they were. They stumbled on through the forest, clutching their precious cages, until Kulume saw the light of a fire. He led them cautiously towards it, but no-one was there and an empty hut stood beside. The place seemed safe enough, so they lay down inside the hut and went to sleep.

In the middle of the night Kulume woke. The fire was out and the hut was dark. Then he heard a voice muttering, ‘The meat smells good. I shall call my brothers!’ and Kulume knew with fear that they were in the hut of a cannibal.

He woke his friends silently, and led them far and fast through the darkness. But as the stars faded and the morning came, Kulume realised with horror that he had left his caged bird behind.

‘We must all go back together,’ suggested one of the boys, though all of them were afraid.

‘No,’ said Kalume. ‘It is all my fault. I must go alone. Don’t worry, I’ll be back’.

‘But what will happen to us if we lose the Chief’s last son?’ wailed the other six boys.

‘Watch my spear,’ said Kulume, planting his assegai firmly in the ground. ‘If it stands still, I am safe. If it shakes, you will know I am in danger. If it falls, I am dead.’ He ran back into the forest.

The sun was high in the sky when the six boys saw the spear tremble, then steady itself; tremble again and bend, before steadying; tremble a third time and shake and almost fall, and then stand still once more. As they breathed a sigh of relief that all seemed to be well, there was Kulume beside them with the cage and the bird in his hand.

‘What happened?’ they cried.

Breathlessly, Kulume told them how he had met an old woman fetching water beside a waterfall. Her waterpot was heavy so he stopped to help her.

‘Where are you going so fast?’ she asked and he told her. ‘You are brave,’ she chuckled and then gave him some meaty fat in a little wooden bowl. When he reached the cannibals’ hut, he was horrified to see four of them rejoicing over whatever or whoever was roasting over the fire. So he slipped inside the hut, found the little cage and the bird warbled softly, as if glad to be with him. Then he made ready to run. But as he was escaping, the cannibals saw him in the firelight.

Quickly, as the old woman had instructed him, he rubbed some of the meat fat on a stone. When the cannibals rushed up, each one wanted the stone. One said, ‘It is mine!’ and swallowed it. Immediately the rest attacked him and ate him. Then they started running after Kulume once more. Twice more, as they caught up with him, he had done the same thing and left the cannibals quarrelling and feasting behind him in their horrid manner.

‘So that is why your assegai trembled those three times,’ exclaimed one of the boys.

‘But you said there were four cannibals,’ worried another. ‘If they stopped three times to eat one of their gang, there must still be one left alive.’

And at that moment the remaining cannibal sprang into the clearing with a bloodthirsty roar. He was huge and hairy and horrible. But he was heavy with all that he had eaten, and no match for seven boys and seven assegais. It was Kulume’s own sharp blade which finally killed him.

For seven long days the Chief had sat gazing into the distance towards the Cliffs of the Falling Goats where his last son had gone adventuring. The sun was already gathering red clouds around it when he heard a shout from his Induna, Mbata.

‘I see seven figures, Nkosi, and they come running.’ said Mbata with joy in his heart.

Across the valley came the cry, ‘It is I, your youngest son Kulume, who speaks with a new name. We bring with us the seven beautiful birds and, what is more, I bring my voice.’

The Chief’s kraal was filled with the sound of shouting and laughter as all his people rushed out to greet the boys. The noise stilled with wonder as they saw each boy standing behind his bird cage, set out in a line across the path. Kulume bowed politely to his father and then ran along the line, cutting open the cages with his assegai. From each arose not a bird, but a tall, young man. The seven lost sons had come to life again.

That night the valley was loud with rejoicing, and the Chief’s long sorrow was turned to joy.

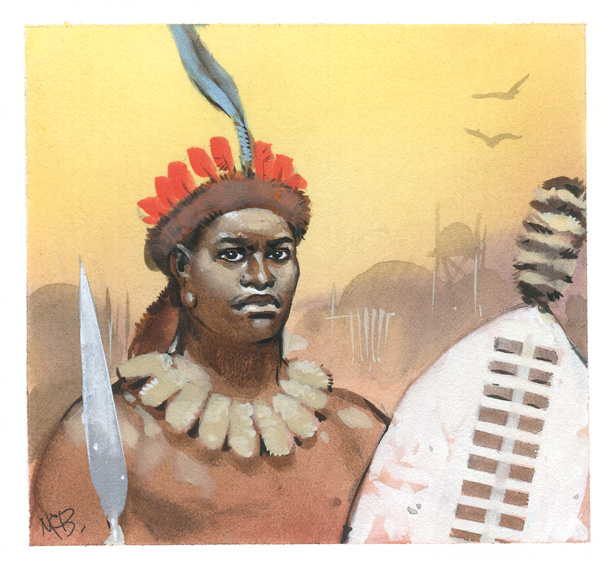

The Zulu

The rolling valleys of KwaZulu-Natal were settled over a thousand years ago by Nguni-speaking tribes probably originating from Zimbabwe. In the early 19th century, the great military commander Shaka made his tiny Zulu clan into a powerful kingdom. Today, almost all the black peoples of Natal (numbering some 7 million) refer to themselves as Zulu. They believe that a powerful force, Nkulunkulu (‘great, great one’) watches over them. Their Zulu folktales remain one of the richest sources of traditional storytelling in Africa.