Drilldown: How Irrelationship Works

An irrelationship routine is the outgrowth of patterns a person develops as a small child to relieve her or his primary caregivers’ anxiety so that the caregiver is able to meet the child’s emotional needs. The caregiver then comes to depend on the child to provide this kind of “caretaking.” If this dynamic doesn’t change, the child will unconsciously continue this caretaking pattern into adulthood, approaching romantic partners and others as someone for whom she or he must perform a caretaking role and on whom she or he depends to act the part of an appreciative audience. Underlying this pattern is a shared wariness of close relationships that short-circuits genuinely intimate relationships.

Hiding from Relationship—in Relationship

Will and Kimberly came from families in which showing feelings or complaining about unmet needs was off-limits. As a result, neither was prepared for intimacy with a romantic partner, which made the unhappy outcome of their marriage all but inevitable.

The thrill of their early courtship never developed into actual intimacy either before or after they were married. After four years together, both felt isolated and subtly devalued; however having never learned skills for sharing feelings and fears, they weren’t able even to bring up the mutual feeling that their connection was fading.

What short-circuited Kimberly and Will’s connection? Received wisdom says that early excitement naturally and inevitably fades as familiarity grows. However, as psychoanalyst Stephen Mitchell cautions us, this may be related to choosing to cultivate stability in a relationship we depend on instead of repeatedly opting for partnerships characterized by “episodic, passionate idealization,” which he views as “a dangerous business.”1

When anxiety controls our relational styles, we’re uneasy around spontaneity, self-disclosure, and the unpredictability of passion. Children who grow up in households that discourage spontaneity and reciprocity are likely to grow into adults who demand carefully scripted romantic relationships. Families in which discussion of emotions or needs isn’t allowed are likely to produce adults who haven’t the skills to process even their own feelings. Typically such individuals lack capacity for genuine caregiving or constructively addressing rough spots in relationships.

Connections based on these deficits often appear to be lopsided: one person’s needs appear to determine the other’s behavior. One party performs and the other accepts and even applauds what the other gives. But in reality, the parties are equally invested in warding off unpredictable feelings and events.

Kimberly and Will’s song-and-dance routine was configured along these lines:

• You’ll accept whatever I do for you and act as if you’re grateful for it.

• I’ll act as if you’re fun to be with and “that’s what’s so special about you.”

• Our interactions will carefully skirt around real issues without us ever indicating that we’re aware we’re doing so.

In a matter of months, Kimberly and Will each felt abandoned by the other, yet neither could have explained why or how. But instead of reaching out to one another, they clung to two rules they’d learned as children: (1) Ignore my unmet needs and negative feelings, and (2) Don’t ask questions about your needs and desires. Ultimately, this was a price too high that left them burned out and wanting out. Their marriage ended, Will observed, with a thud rather than an explosion.

Exercise: Caretaking Agreements (Couples)

This table provides examples of caretaking agreements in a relationship and is followed by questions to help you clarify characteristics of your own relationship that are markers of irrelationship.

Caretaking Agreement Examples |

How Do We Feel in the Relationship |

What Is Its Impact on Our Relationship |

I diligently provide caretaking for my partner who needs a lot of help. |

I feel resentful and overburdened; you feel resentful and unappreciated. |

Our roles deflect conflict and in them we feel increasingly estranged, but we can’t see any way to address issues or solve problems. |

I accept my partner’s caretaking whether it meets my needs or not. |

I feel unheard and unable to express what I need. You try even harder and don’t seem to listen to what I say. Nothing really seems to make me feel better. |

We’ve lost touch with the feelings that brought us together; we feel uneasy without knowing why; and we see no other options and feel hopeless. |

What kinds of agreements, conscious or not, have you made with each other about what behaviors are acceptable for you to offer one another? Using the previous table as a guide, discuss unspoken agreements you see yourself and your partner living by and how these agreements play out in your day-to-day lives.

Creating a safe space for discussing relationship roles and other anxiety-provoking subjects is the primary tool for building relationship sanity. The following statements will help bring significant markers of irrelationship into focus. After answering each numbered item individually, share and compare your responses.

1. I should be the solution to my partner’s life. (My partner should really “need” me.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

2. My partner should be the answer to what I need in my life. (My partner will solve all my problems.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

3. Love mostly means taking care of my partner. (I want someone who needs me to look after him.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

4. Love means my partner is always there to take care of me. (My partner is always around to make sure I’m okay.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

5. When I’m taking care of my partner, I sometimes feel unappreciated. (My partner doesn’t realize all I do for him or doesn’t value it enough.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

6. Things are too one-sided between my partner and me. (I do all the giving, and she just takes.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

7. Being in a relationship is more work than pleasure. (Having a partner drains me and leaves me feeling unfulfilled.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

8. My partners have usually been women or men who didn’t really listen to me. (My partner doesn’t take a lot of trouble to make herself available and to reassure me.)

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

9. Overall, my relationships with partners have been disillusioning.

a. Agree

b. Not sure or sometimes

c. Disagree

The more you agree with these statements the more likely it is that you look for partners who view caretaking as a baseline expectation for a relationship, which is highly suggestive that irrelationship figures prominently in how you seek to construct relationships with romantic partners and others—including family members.

In the exercises and chapters that follow, we’ll look at what traits you consider desirable in partners and friends versus traits that make you feel uneasy or frighten you.

The roles defining irrelationship are the Performer and the Audience.

• The Performer is the overt caretaker who appears to be calling the shots by deciding how the Audience needs to be helped and creating a caretaking routine to fill that need.

• The Audience, the apparently passive receiver of the Performer’s help, is actually caretaking the Performer by appearing to accept and benefit from whatever she or he offers.

The Price of Quieting Our Anxiety

When anxiety is well managed, we feel, think, and function better. But when we handle anxiety—or any other feeling simply by blocking our awareness of it—we risk losing guidance of all our emotions because our minds don’t allow us to pick and choose which feelings to ignore. If you numb one, you risk numbing them all.

But the feelings don’t just go away: sooner or later, some experience apparently unrelated to our denied feelings will trigger an overwhelming emotional reaction that will seem to come out of nowhere. Such experiences ultimately do little to relieve unaddressed anxiety.

Dysfunctional Behaviors Used to Quiet Anxiety

As mentioned previously, adults continue song-and-dance routines learned in childhood to manage feelings of anxiety associated with would-be intimate relationships. But this mechanism only suppresses awareness—not the feelings themselves—so that the disturbing impact of those feelings continues in the unconscious mind without our knowing it.

In many cases, suppressing the awareness of anxiety is jointly and tacitly agreed upon by the whole family. Sometimes one family member takes on a monitoring role and has the job of creating a distraction when she or he senses that anxiety is approaching an “unsafe” level, thus allowing the family’s emotional equilibrium to return to “normal.” Often, the person taking on that role continues it throughout her or his life.

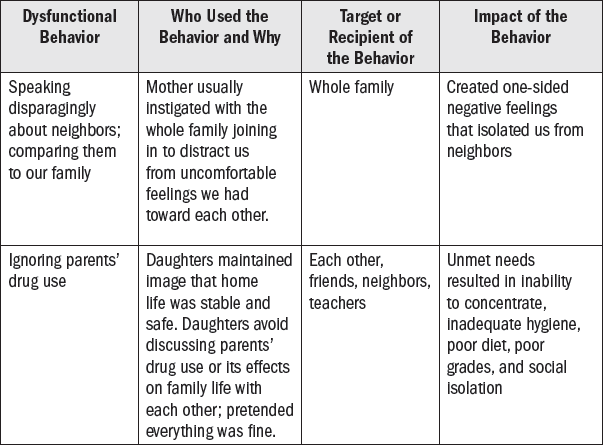

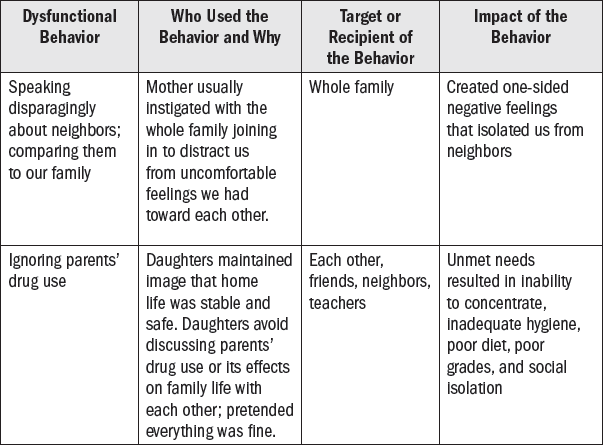

Exercise: Dysfunctional Behavior (Individuals)

The following table looks at behaviors commonly used to block awareness of anxiety, who performs the behaviors, and their impact. For each example, read from left to right to appreciate the underlying dynamics and purpose of the dysfunctional behavior.

Using the previous table as a guide, analyze your most significant relationships.

• What dysfunctional behaviors of your own can you identify from the past and present that affect how you relate to others?

• How might those behaviors have developed as a result of experiences you had growing up?

• What behaviors in people close to you can you identify that kept them at a “safe” distance from others?

• How does that history connect with your own self-protective song-and-dance routine?

Attachment Style and Self-Other Experience

High-functioning people appear emotionally sturdy and secure, while those affected by irrelationship have locked down their feelings to conceal what psychoanalysts call an insecure attachment style. This lockdown limits access to self-other experience—that is, limits perception of ourselves and others in (potentially) intimate relationships.

Research has identified a relationship between individuals’ experiences with caregivers as children and how they connect with others as adults.2 The façade created by people affected by irrelationship deflects their attention from anxiety related to poor caregiving they received as small children. Identifying this anxiety is essential to dealing with the fear driving irrelationship.

Insecure attachment styles may also be described as either avoidant or anxious, respectively, depending on the quality of empathy that had existed between child and caregiver, the child’s innate traits, and the fit between the child and the attachment styles of the child and caregiver.3

People with a secure attachment style remain essentially grounded during emotional disruptions and even during severe life crises. They typically weather such experiences without becoming derailed, even in cases of deep disturbance, returning relatively quickly to equilibrium and growing as a result of the experience.

By contrast, people with insecure attachment styles experience the normal ups and downs of life as so anxiety provoking that they either ignore or avoid them or become preoccupied with them. In both cases, they’re often unable to work through and integrate feelings and conflicts productively, so they defend themselves by avoiding real interpersonal connections or confrontations. At the same time, they may unreflectively jump into relationships that seem magically to offer relief or solve problems without much effort.

The interplay between two people with insecure attachment style is prone to snowballing rapidly into a crisis. For example, if an adult who avoids intimacy gets involved with someone who is preoccupied with a potential partner, the avoidant person will increasingly retreat from the other, provoking an increasingly anxiety-driven pursuit by the preoccupied person. This creates a cycle whose resolution is usually unpleasantly dramatic.

Similarly, deadening of a relationship is likely if two avoidant persons leave issues unresolved for prolonged periods. Long-standing unmet needs that go unaddressed lead to resentment, chronic feelings of deprivation, and suppressed contempt. If communication doesn’t improve, deep sadness and unresolved grief develop.

The habit of blocking consciousness of one’s distressing emotions is likely to lead to difficulty tolerating any frank emotional experience, negative or positive, including empathy, compassion, and love.

Claiming and Reclaiming Closeness

Are people living with irrelationship doomed to lives barren of intimacy?

That’s not what attachment theory or our experience with clients indicates. An “earned secure attachment”4 can be created by allowing compassionate empathy to break down our song-and-dance routines if we’re willing to explore our feelings, needs, and old ideas about relationships.

Managing many moving parts can lead to so much confusion that it may make us want to return to hiding in our song-and-dance routines. But deciding to keep the door open to learning new ways of interacting with others can be enough to start the process of building a new life.

Exercise: Reflecting on Your Own Family (Individuals)

Is irrelationship in your family? The following brief exercise may provide some clues.

Write down the names of people you remember who figured significantly in your life when you were a small child—caregivers, other family members, neighbors—it could be anyone. Then write reflections or even just singleword impressions you have about each person.

• What do you recall about each person that influences how you view or relate to others as an adult?

• What connections do you see between how they treated you and how you behave toward others now?

• What do you protect yourself from by keeping your distance from others?

GRAFTS: Types of Song-and-Dance Routines

Our song-and-dance routines are techniques we developed as small children to change our early caregiver’s emotional state, so they were able to take care of us. Children in families where this occurs become exquisitely perceptive of other’s emotional states and unspoken needs and become masters at managing other people to keep them from being angry, upset, or sad. Over time, the routine becomes ingrained and shapes our view of ourselves and everyone and everything that is part of our world. Our identity becomes organized around the need to be a caretaker and our demand that those around us align with our caretaking routines. So what does this look like in a child?

A wide variety of patterns of interaction—for which the authors have devised the acronym GRAFTS—become grafted onto a child’s personality in response to her or his experience with early caregivers. The following table includes brief descriptions of the GRAFTS and why the child starts acting them out.

Explanation |

||

G |

Good |

We believe our caregiver needs us to be a “good” girl or boy, driving us to be good all the time with everybody. |

R |

Right |

We’re driven to do everything exactly right, hoping, and finally believing, that doing so will make our caregiver feel better. Sometimes this develops into a need to be strong or competent in all situations. |

A |

Absent |

We believe we can help our caregivers by staying out of their way. This is often seen in children of a severely depressed parent but sometimes in children whose parents are not engaged or who have poor coping skills. The absent routine is virtually always characteristic of the Audience. |

F |

Funny |

The child is constantly “on,” looking for ways to make the caregiver laugh, thus dispelling her or his negative emotions. When we figure out what behavior is most effective as a mood changer, we make it our “first line of defense” against anxiety. |

T |

Tense |

This adaptation is a constant state of unconscious anxiety that keeps us walking on eggshells so we don’t upset our caregiver. We also avoid calling attention to our own needs or even thinking about them. |

S |

Smart |

In households where intelligence is valued, children elicit attention by making themselves knowledgeable in areas calculated to please the caregiver. Children locked in this behavior often deprive themselves of exploring their own interests. |

When we use these GRAFTS techniques and they seem to work, we learn to believe we can fix our caregivers by changing their mood, which makes us feel safer.

Exercise: GRAFTS Assessment (Individuals)

Do you recognize any of these GRAFTS behaviors in yourself or someone close to you? The following is a quick assessment to help you decide.

• Do you remember times you used any of the GRAFTS? Do you remember why? Explain.

• Are you aware of having continued that GRAFTS behavior as you got older? How did it change?

• Whom have you used a GRAFTS behavior for? How did they respond?

• How did you know when to use a GRAFTS behavior? Are you aware of currently using any of the GRAFTS in the following situations: workplace, friends, family, or romantic involvements? If so, why do you?

• Has using a GRAFTS behavior had an impact on your social life? Physical health? Work life and finances? Your state of mind?

• Do issues related to GRAFTS have anything to do with your choosing to work on your relationship now?

Exercise: GRAFTS Role Reversal (Individuals)

Each item in the GRAFTS table represents a role reversal in which a child takes on a caretaking role for the caregiver. This distortion of roles and boundaries profoundly impacts the child’s feelings of safety.

In the following exercise, see if you can relate to the examples given. Consider each GRAFTS behavior, and then list ways that your own behavior had an effect on how you related or still relate to others.

Role Reversal |

Who I Performed for |

Impact on Me |

My mother was always criticizing herself compared to other mothers, so I worked harder at school hoping she wouldn’t be so down on herself. |

My mother |

I ended up acting like a “know-it-all” at school, which made other kids avoid me. |

My parents fought a lot, but they’d stop when I’d pretend I was on stage doing a singing or comedy performance. |

My parents |

I made myself responsible for their relationship. Sometimes it backfired, and they’d yell at me for being silly. |

Exercise: GRAFTS Family Rules (Individuals)

In the following exercise, list examples of how family song-and-dance routines became inflexible family rules when you were a child. Then describe how this affected you. Some examples are listed in the table.

This Rule Came Out of Routines Enacted with |

This Rule’s Impact on Me |

|

Don’t show your feelings. |

Dad |

When family arguments broke out, I’d leave the room, so nobody would know how afraid I was. I was left in isolation with my fear. |

Always be on my best behavior outside the house, so nobody suspected anything was wrong with our family. |

Mom |

Since I could never just be myself, I made almost no friends in school. |

GRAFTS caretaking roles can be replays of old family rules that get in the way of family members’ caring for one another. These rules even enable parents to avoid responsibility for giving their children the care they need.

After reviewing the broad-brushstroke examples in the following table, list your own examples of song-and-dance routines (GRAFTS) that became inflexible rules in your relationships and describe how this affects how you connect with others.

Rule |

How This Rule Plays Out in Our Relationship |

How This Rule Impacts Our Relationship |

Deny everything. |

Instead of openly discussing troubling issues with my partner, I ignore problems and pretend everything’s fine. |

Even though we live together, mutually agreeing to ignore troubling issues leaves both of us feeling isolated and alone. |

Blame others. |

I tell my wife we have money problems because she can’t get a decent-paying job. |

I used my salary as justification for humiliating my wife, who already feels bad about how much she makes. This also makes her feel like she’s not entitled to say anything back to me. |

Note that caretaking routines are actually the opposite of showing empathy—and in fact actively get in the way of doing so. Pummeling others with caretaking makes it impossible for them to offer anything in return. This is a primary purpose of irrelationship.

Exercise: GRAFTS Roles and Rules (Individuals and Couples)

Revisit the GRAFTS exercises that you have already completed, identifying ways that you and your partner act out roles and rules that you remember from the household in which you grew up. After identifying your GRAFTS roles, use the examples in the following table to help you to draw out how your GRAFTS routine(s) originated and how they play out in your relationships.

Roles I Play in Our Relationship |

How and Where My Role Originated |

Effects of My Role on Both of Us |

I often play the victim. |

It’s how my father responded to my mother’s domineering behavior to keep the peace. |

I keep my real needs hidden from my partner for fear of disturbing the peace and end up feeling neglected and abandoned. |

I stick to a bystander role when anything goes wrong in our relationship. |

When I was a kid, we lived with my father’s parents. They constantly criticized my mom, but my father never stood up for her. |

When my partner has problems with others, I silently look for ways to blame him for it. |

Next identify and list the unspoken rules that have been established in your relationship. Refer to the table for examples.

Relationship Rules I’ve Implicitly or Explicitly Agreed to |

Where I Learned These Rules |

How These Rules Affect Our Relationship |

We have to stay together at all costs. |

My parents stayed together, even though they hated each other. |

The threat of being alone is so scary that I’m afraid to reveal negative feelings to my partner for fear he’ll leave me. So I pretend everything’s okay. |

We don’t talk to each other about behavior we don’t like. |

My parents never argued in front of us or allowed us to argue about anything. |

Discussing relationship issues is out of bounds, so I’m always tense and tiptoeing around my wife. I don’t know how long I can continue this. |

Learning to open up about your part in your song-and-dance routine is the beginning of creating genuine connection on which to build your shared life. You can start right now by reflecting on your experience as a couple. Describe ways that roles played out in your family of origin negatively affect your relationship or relationships now. Use the examples in the following table to get in touch with your own feelings and thoughts and get your process started.

Roles Each of Us Acts Out in Our Relationship |

Origin of These Roles in Our Individual and Shared History |

Effects of These Roles on Our Relationship |

I’m like a cop monitoring everyone’s behavior—especially my partner’s. I’m always ready to pounce if he does anything I don’t like. And I don’t always wait until we’re in private to do it. |

My mother was always lying in wait for my father to do the least little thing she didn’t like. |

I’ve caused pain and created distrust that makes my partner unwilling to confide in me or go anywhere with me. He says he constantly walks on eggshells around me. |

I’m always the martyr. I congratulate myself for putting others’ needs ahead of my own. |

My father had a stroke when I was a teenager. Mom made a point of letting everyone know about the sacrifices she made to take care of him. Meanwhile, if we kids needed anything, she said we were selfish. |

People outside the family say I’m a saint, but nobody in my family even tries to talk to me since the day my husband blew up and said I’m always complaining about what I have to do for others. He doesn’t even try to listen to my side of the story, and now I feel cut off from my own family. |

Now describe ways that rules negatively affect your relationship. The following table may provide helpful examples.

Rules We’ve Implicitly or Explicitly Agreed to |

Origin of These Rules in Our Individual or Shared History |

Effects of These Rules on Our Relationship |

Each partner is allowed to believe that what they contribute is good enough. |

My older sister acted as if our parents’ undependability caused no problems in our family life. But as soon as she was old enough, she left home and never looked back. |

I never complain about my partner’s contribution to our home life, but now I resent and feel resented by her. |

We will pretend everything’s fine. |

My mother was terrified that the neighbors would find out about my father’s drinking and the problems it created at home and on his job. |

Early in our relationship, my boyfriend and I never found a way to talk about any kind of relationship or household issues for fear of creating problems. Now we barely talk to one another beyond small talk as we leave for work. Our schedules make it impossible for us to have dinner together. Sex has disappeared. |

Self-Other Help Exercises

Up to this point, you’ve been looking at your own histories, feelings, and behaviors to see how they align with the irrelationship adaptation. Now you’re going to move into learning techniques of Self-Other Help—simple tools that have the power to undo what your histories have created and open a space for living in relationship sanity.

Exercise: The Audacity of Listening (Couples)

Having explored the dynamics of irrelationship in preceding sections, the following questions will help you explore your past relationships and articulate how you’d like to change.

Begin by explaining to one another how you understand irrelationship: what it is, how it works, how it affects you, and things about yourself and your relationship that you’d like to change.

1. Share feelings about what it’s like to see your interactions as self-protective devices that get in the way of growing closer to each another.

2. Talk together about what you believe you were protecting yourself from by using these devices.

3. Discuss what it might be like to be open to unpredictable feelings, especially anxiety, and what might happen if you were.

Exercise: Reflection (Couples)

Learning to practice open dialogue with those we’re close to almost inevitably opens our eyes and ears to parts of ourselves that we may not easily become aware of otherwise. This is key to practicing compassionate empathy.

The following practice helps to disarm the tendency to get down on yourself about parts of your past that you’re uneasy or embarrassed about. Reflecting directly on such experiences tends to disempower leftover anxiety or shame. This short-circuits the temptation to retreat into the familiarity and security of irrelationship.

1. Tell your partner about an experience in the past—distant or recent—that made you feel anxious, embarrassed, or guilty.

2. As you reflect aloud on that experience, deliberately try to reconnect with the discomfort it caused you.

3. Write down what it’s like to return to that experience and its associated feelings.

Exercise: Approaching Compassionate Empathy (Couples)

Sit in silence together for one to two minutes and try to focus only on your breathing. Setting a timer may be helpful.

After the period of silence, take turns saying each of the following statements to one another.

• Blaming and punishing harms the process of getting well for both of us.

• We can help each other feel accepted and cared for.

• We can learn to feel safe enough to touch and be touched by each other.

After a pause, tell each other about feelings or memories that came up as you did this practice. Write them down, noting similarities in what came up for the two of you. Afterward, explain in writing your ideas about where this practice could lead your relationship.

Staying on Target: GRAFTS versus Relationship Sanity Assessment

Understanding your own song-and-dance routines—and how they are expressed by GRAFTS—is an essential step on the road of relationship sanity. A major aspect of your work here has to do with forming a better understanding and acceptance of yourself—your whole self with needs and desires—through your relationships with others. Song-and-dance routines are a a code that allows those invested in irrelationship to be protected from hearing, while listening is the vehicle of compassionate empathy.

Key Takeaways

• The process of receiving (accepting) and giving care that forms the foundation for relationship sanity is the best way to work through irrelationship and the key to building and maintaining healthy relationships in our life.

• Together we can build self-compassion and acceptance.

• Through this process we learn to allow life to happen without any interference.

• In this process, I will—and we will—be able to finally answer the question: What do I need?

• In this process, I will—and we will—be able to finally answer the question: What do I really need?

Now pause and look at each other. Use free association to discuss any thoughts or thought fragments, feelings, reflections, and analysis of where you were and where you’re headed—individually and as a couple—along the road of recovery from irrelationship, the road of relationship sanity.