The 40-20-40: Relationship Sanity in Action

Nurturing a middle ground in which differences with those around us can be negotiated is necessary for relationship sanity. This work is done jointly by the invested parties who are willing to learn to communicate honestly and effectively with each other.

A nemesis of relationship sanity is the Credit-Blame Syndrome. The Credit-Blame Syndrome uses a lot of finger-pointing—some verbal, some not—but never really meets anyone’s needs or solves problems. Dismantling irrelationship, then, isn’t about learning how to be fair when placing blame: it’s about examining how our life choices have stood in the way of meeting our real needs.

How will you know when your investment in irrelationship is diminishing? The answer is that you’ll know—you’ll feel it—when what you give in your relationships feels balanced with what you receive back from your partner.

The 40-20-40 Model of Relationship

So how does the 40-20-40 help address this situation?

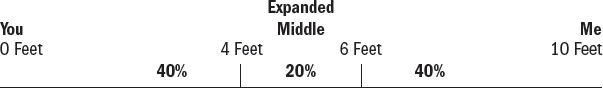

Imagine that you and your partner are sitting in chairs at a table ten-feet wide. A line bisects the table at the exact midpoint, leaving five feet between each of you and the midpoint—ten feet apart. Imagine a line in the exact midpoint between you—a 50-percent line. That leaves five feet between each of you and the middle.

Next imagine expanding the width of the line in the middle of the table so that it occupies an area that’s 20 percent of the width of the table, leaving 40 percent on each side of the midline for each of you.

This model illustrates a reciprocal dynamic between two people. If responsibility for what goes right and what goes wrong in relationships could be split evenly, balancing giving and receiving in relationships would be simple. However, everyone coming to a relationship brings histories, traits, needs, and desires, making the balancing process complicated and messy even for those who do have insight into what they bring to the table. In other words, a relationship is always more complicated than the sum of its parts.

The 40-20-40 is a Self-Other Assessment in which the parties examine individually and jointly the part each plays in the relationship and the effect her or his contributions have on each other and the sum. Each party may take no more than 60 percent and no less than 40 percent responsibility for any given issue. This leaves a 20-percent space for a couple to meet in the middle where they can safely articulate their issues and experience without blaming. This allows nonjudgmental validation of each other’s experience, placing the couple on a better footing for mutual understanding and shared problem solving.

Gettin’ the Band Back Together

Tyrone shared his experience of finding out that the 40-20-40 can work with others besides intimate partners.

“Janelle and I had been using the 40-20-40 for a while when a major battle of wills began to shape up in my band. Then it hit me: maybe guys are so wrapped up in their own issues that, for whatever reason, they just can’t hear each other. So I thought, ‘What about the 40-20-40?’”

Irrelationship roles can develop between virtually anyone in any situation in which a person is invested but feels vulnerable and at risk.

“The band had busted up over and over again—usually with a lot of drama. But nobody was talking about their own feelings: we’d just blast one another when we got pissed off. And sometimes it was obvious we weren’t blasting somebody that we had a real issue with. It seemed like a perfect situation to try getting the guys to look at what’s really going on instead of just getting mad and getting out.”

Tyrone’s band wasn’t just a bunch of kids jamming together in somebody’s garage: they had high-level name recognition in their area of the country and had even been heard and approached by a scout from Los Angeles. But their on-again-off-again relationship not only put the band’s name recognition but also their finances in jeopardy—something their manager repeatedly warned them about.

“Things were a real mess at that point. One of the guys was especially ticked off at our manager. We had to do something if we weren’t going to blow up past the point of no return. So I told the guys, including our manager, how the 40-20-40 worked. At first they were kind of unsure about it but finally agreed to give it a try.

“From the start it reminded me of me and my wife: the singer was always acting like he’s doing us a favor by just showing up—usually late—but nobody ever called him on it. The bass player made it no secret that he was always auditioning for other bands—or saying he was going to. Our drummer always stayed out of everything—kept in the background and never said jack shit, no matter how pissed off anybody got about anything, including his mistakes.

“But the weirdest thing was a couple years ago when our sax player died—OD’d on heroin. I’m telling you, everybody loved this guy; but, suddenly, there we were dead in the water, like for months. After his memorial, people started missing rehearsals—had other things they had to do or they just didn’t show up. But we never talked about it—just like we didn’t talk about Ronnie dying, and we never looked for another sax player.

“And then our manager! Jeez! You’d think he was our mother, constantly bugging us about how we spent our money, what we did with our time—and I mean our free time! We had this laundry list of messed up stuff, and everybody was walking around like everything was cool.

“Well, it took some doing, but I got everybody to agree to meet at a diner we went to sometimes, and I explained the 40-20-40 to them—said I thought we had a lot of stuff we needed to work on and told them how it had helped Janelle and me. And they knew that was for real because they all knew something had happened that had really changed our marriage. So anyway, bottom line, they were willing to give it a try.

“I explained the ground rules, and one of us kept the stopwatch. And it was hard at first because everybody had all this stuff going on with themselves and about the band. But the funniest thing was that when we started sharing, every single one of us admitted we were afraid to say what was on our mind because we were afraid of saying something that would ruin the band!

“The hardest part for everybody was talking about what was going on without blaming somebody, or, the flipside, without somebody feeling attacked when they really weren’t. That’s what goes on in the real world too: everybody’s so into their own image that you just instinctively say, ‘I’m cool, I’ve got this.’ Well, we finally got to where we were all able to say that we weren’t cool, or we didn’t know what was up or how to handle it. In fact, I think the best thing for the band has been learning to trust each other like that. It makes you feel like you’re part of something real.

“And, man, it’s deep sometimes. I remember when Jorge was still pretty new to the band, and he was badmouthing our manager one time. But instead of getting mad, our manager called a 40-20-40! And what happened? Jorge, the new guy, admits that he’s insecure playing with us—doesn’t know if he’s a strong enough artist. And he was looking over his shoulder, waiting for our manager to tell him he didn’t make the cut. Well, this was all because our manager never said anything to Jorge about his playing. And that was where we all got to help him out because our manager never says anything about anybody’s playing. But how could Jorge know that? He just took it personally. So we got to tell him that we all had stories about our manager, which totally changed everything. Funny thing is, after that, Jorge’s playing went off the charts!

“One of the biggest things to come out of this is that we love playing together and we love saying so to each other. Of course we have our issues, but nobody’s afraid somebody’s gonna blow up the band if we talk about it. In the past, we acted like a bunch of martyrs, keeping all that stuff to ourselves. And then, when Ronnie died, we felt sucker-punched, but nobody felt like he could bring it up. And I gotta tell you, when that was going on, our rehearsals were horrible. It felt like nothing was ever going to be right again.

“Well, it’s not like that anymore: if something’s bothering somebody, we can’t give it a pass because we care about each other; and anyway, it affects how we play. So if we need a 40-20-40, we stop rehearsal and have a 40-20-40.”

Exercise: Practicing the 40-20-40 (Couples)

Revisit the Joint Compassion Meditation in Chapter 1 before proceeding to the 40-20-40 practice with your partner.

Previous exercises lay the groundwork for the next exercise by creating a safe space for risk-taking. The 40-20-40 allows couples (or larger groups) to hit pause when conflict occurs to provide an opportunity for identifying and addressing problems jointly. Begin your practice by doing the following.

• Identify an issue or disagreement in which each party is willing to discuss her or his part.

• For agreed upon time-intervals, each partner take turns describing her or his own part, positive and negative, in the issue. Start with an opening exchange of five minutes each, with a series of three follow-up exchanges of three minutes per person. As you proceed, take note of feelings and thoughts your partner reveals that you identify with and share these in your next turn to share. After completing four exchanges, assess the 40-20-40.

Remember that the purpose of this practice is not to identify points of criticism or blame but to promote taking co-ownership of your relationship. But go easy on yourselves: most of us require practice to learn to remain within one’s own 60-percent zone.

Use the categories listed here to assess your practice of the 40-20-40, looking for strengths and areas you can improve. As you consider the following table, which shows each dimension of relationship sanity on a spectrum from low to high, make note of whether you more strongly identify with the items on the left compared with the items on the right.

Compassionate Empathy |

|

I felt distance between what I thought and what my partner experienced. I felt criticized and unheard. I felt uneasy and unsure about reaching my partner. |

Listening to and hearing one another felt natural and wasn’t confused by my own feelings. The practice felt “caring” and like an opportunity to learn from each other. |

Interdependence |

|

I feel that I’m better able to manage my life without disturbances like this. We have so many problems that we’d probably be better off on our own. |

Though we have problems, I feel that sharing like this strengthens us and makes our lives better. |

Independence |

|

The 40-20-40 Exercise highlighted that our relationship doesn’t help me feel less anxious or isolated. |

The 40-20-40 Exercise promoted acceptance of differences without disturbing my appreciation for my partner. |

Now imagine a relationship where you no longer need to play the good, right, absent, funny, smart, or tense caretaker by either Performing caretaking routines or playing appreciative Audience to ineffective care. This is an in-between space—a space between irrelationship and relationship sanity to be filled in with compassionate empathy before it regresses. Consider the following questions.

• Being released from your role, who are you now?

• Who have you become? Who are you becoming?

• How does this change feel frightening or bad (e.g., “I’m a bad person because I am selfish and too expressive of my own needs.”)?

• And how does this change feel like a relief or otherwise good (e.g., “I feel compassion toward my significant other but I understand that it isn’t helpful for me to suppress my own needs until I am ready to burst.”)?

• How has acting the part of the Performer/Audience made you suffer or feel anxiety or anger, and how do you feel about seeking peace and joy in the future?

• How has acting the part of the Performer/Audience made the other person suffer or feel anxiety or anger, and how will you think about this in the future, so you can be more active and engaged, still a great listener, but not disengaged in unhealthy ways?

Take five to ten minutes to reflect on this experience. If you are feeling distressed, consider hitting pause to think, feel, and reflect. Afterward do something for yourself to practice the behavior of accepting and receiving something positive, even soothing, for yourself—generosity, kindness, gentleness. Remind yourself that, in the past, you and your partner have used our compulsive caregiving song-and-dance routines to block yourselves from accepting and receiving.

Then discuss the following questions with your partner.

• What aspects of practicing the 40-20-40 seemed to go well?

• What was difficult about it?

• What would you like to do differently next time?

Staying on Target: The Blame Game versus the 40-20-40

Research shows that harsh self-criticism undermines motivation, while compassion promotes motivation. Together, you can use the co-creating of compassionate empathy to help establish a new way of relating that fosters the development of the capacity for discernment: the ability to see and appraise oneself through the expanded experience of Self-Other Help.

Allowing yourselves to receive kindness and balance, you can put yourselves into mutuality with others and recognize that the trap of destructive self-criticism has been used as an unconscious defense from opening up to the care—acceptance—of others. By opening up to Self-Other experience, you can cultivate an appreciation and affection. You can develop a way of relatedness characterized by encouragement and support and by understanding where things went the wrong way and making the necessary course corrections without getting mired in traps of self-sufficiency, i.e., isolation.

Key Takeaways

• We co-create ways to make practical use of the 40-20-40 Model, as implemented together via the Self-Other Assessment (and in groups via Group Process Empowerment) that allows us (or all in the case of groups) to (1) address an issue, conflict, or problem together or (2) hit pause and then consider our own contribution—good, bad, and in-between—to the issue at hand.

• We understand how to establish a safe space for each of us to begin to take risks, take personal inventory—our own and not each other’s—and care for the developing relationship sanity that is replacing irrelationship.

• We consider ways in which self-criticism can be replaced by compassionate empathy and how this—like a new pair of glasses—supports an experience of Self-Other, empowerment, and discernment as a way to feel safe. It can be an effort to

a. keep from making the same mistakes over and over again;

b. become a real collaborator in partnership with real people defending themselves from intimacy;

c. better understand our part in current interpersonal dilemmas and make good with people we may have offended;

d. keep a connection going with loved ones from the entirety of our history by recognizing that opportunities for working through historic conflicts will play out with significant people in our current lives—that irrelationship will rear its head in the relationships that threaten us with intimacy now.

Now it’s time to pause again and assess your progress in moving toward the real goal: relationship sanity. In that pause, stop and give yourself time for free-association. Write down any thoughts or thought fragments, feelings, reflections, and analysis of where you were and where you’re headed—individually and as a couple—along the road of recovery from irrelationship. Then discuss between yourselves.