The base nation as we know it was born on September 2, 1940. It is a vastly underappreciated moment, generally treated as a small detail in World War II history books. But it was then, with the flash of a pen, that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt began the transformation of the United States from one of the world’s major powers into a global superpower of unparalleled military might.

On that momentous day, more than a year before the United States entered the war, Roosevelt informed Congress that he was authorizing an agreement with Britain: the country would provide its nearly bankrupt ally with fifty World War I–era destroyers in exchange for U.S. control over a collection of air and naval bases in Britain’s colonies.

Although such a pact should have required congressional approval, Roosevelt simply declared it done. Under what became known as the “destroyers-for-bases” agreement, the United States acquired ninety-nine-year leases and near-sovereign powers over bases in the Bahamas, Jamaica, St. Lucia, St. Thomas, Antigua, Aruba-Curaçao, Trinidad, and British Guiana, plus temporary access to bases in Bermuda and Newfoundland. Roosevelt called the agreement “the most important action in the reinforcement of our national security since the Louisiana Purchase.”1 Whether the deal was quite so important to national security is questionable. But in terms of its transformative effect, there was little exaggeration in comparing the acquisition of these bases to the 1803 treaty that nearly doubled the nation’s size. The leases’ ninety-nine-year length reflected similarly grand ambitions: President Roosevelt intended to cement the global power of the United States for at least a century to come.

The roots of Roosevelt’s remarkable decision stretch back to the era surrounding the Louisiana Purchase. Beginning shortly after independence and continuing through the 1800s, the United States built up a small but significant collection of extraterritorial bases. This collection reflected the unabashedly imperial dreams of U.S. leaders and allowed the United States to join the ranks of the world’s most powerful countries by the turn of the twentieth century.

The unprecedented profusion of U.S. bases that emerged from World War II, however, represented a quantitative and qualitative shift in the nature of American power, transforming the country’s relationship with the rest of the world. By war’s end, the size, geographic reach, and total number of U.S. bases had expanded dramatically. Never before had so many U.S. troops been permanently stationed overseas. Never before had U.S. leaders thought about national defense as requiring the permanent deployment of military force so far from U.S. borders. After World War II, the United States commanded an unparalleled global military presence, unmatched by any prior people, nation, or empire in history.

THE PRY BAR OF CONQUEST

Since the days of ancient Egypt, Rome, and China, military bases—especially bases abroad—have been a key foundation for imperial control over lands and people.2 The Egyptian Middle Kingdom positioned military strongholds on the borders of its empire, while fortified cities were the norm across the fertile Middle East from Babylon to Jerusalem. The acropolis, which we now think of as the hilltop home of the Parthenon in Athens, originally referred to mountaintop citadels of the kind that appear from Israel’s Masada to Machu Picchu in Peru.3

Rome, too, was an acropolis, and the Romans built temporary “Caesar’s camps” and castra stativa—permanent bases—across the reaches of their empire. Some Roman fortresses later provided foundations for the castles built by England’s Norman invaders. The Tower of London, one of Britain’s iconic symbols, was originally a foreign base built by William the Conqueror shortly after 1066.4 When Columbus first sailed to the Americas, he ordered the construction of a fort on the island of Hispaniola, in today’s Haiti, using the splintered timbers of the Santa Maria.5 On the Genoese sailor’s second voyage, in 1494, he anchored in the bay he called Puerto Grande and we now call Guantánamo.

Today, across the Americas, tourists still visit the remains of the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, French, and British bases that followed Columbus’s first fort in Hispaniola. These tourist attractions are monuments to bygone empires and to the role that such fortifications played in the colonization of the Americas. France established its first bases near Parris Island, South Carolina, in 1562, and on the St. Johns River in Florida in 1564. The Spanish followed in Florida, San Juan, and Havana. Britain set up its own bases in North Carolina, Virginia, Massachusetts, and well beyond as its colonial power peaked in North America shortly before the American Revolution.6

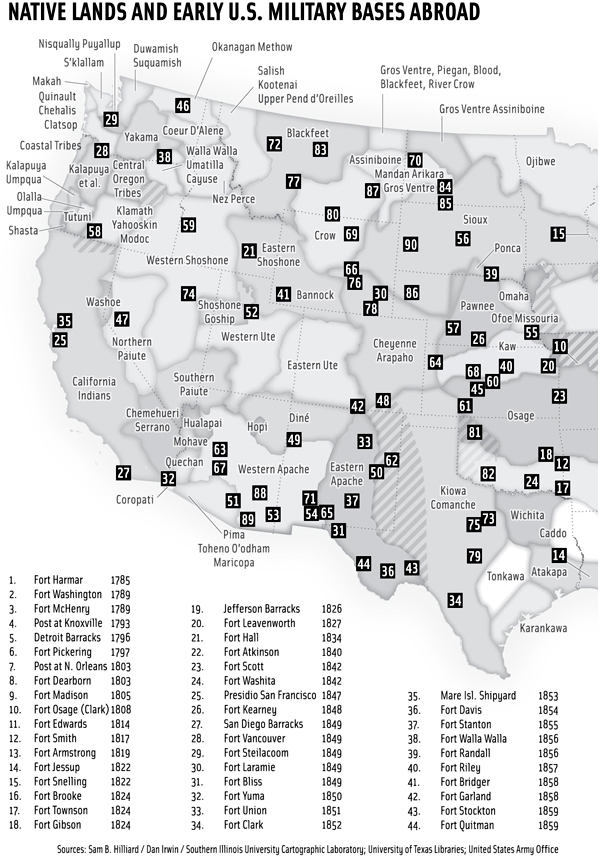

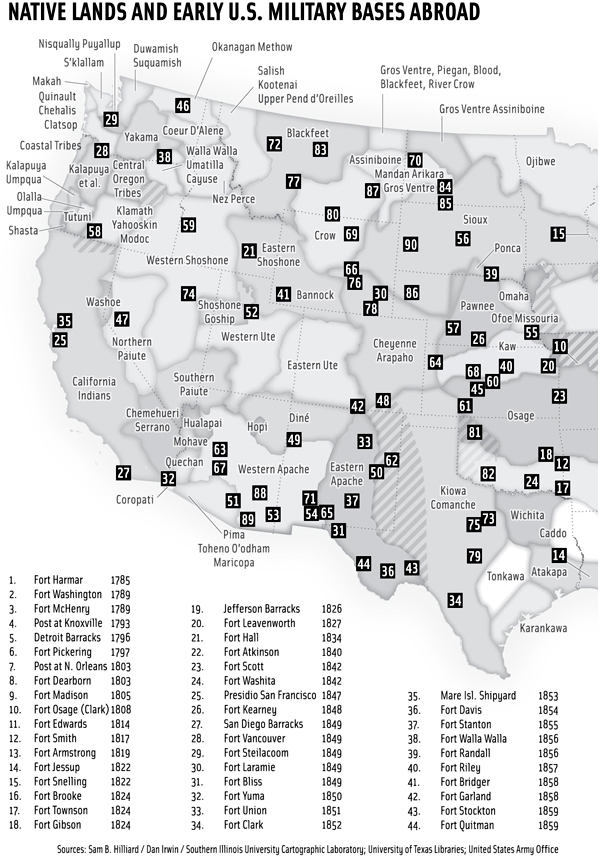

While scholars generally identify Guantánamo Bay as the first U.S. military base abroad, they strangely overlook bases created shortly after independence. Hundreds of frontier forts helped enable the westward expansion of the United States, and they were built on land that was very much abroad at the time. Fort Harmar, built in 1785 in the Northwest Territory, was the first. Others appeared in today’s Ohio and Indiana, including Forts Deposit, Defiance, Hamilton, Wayne, Washington, and Knox. Each of these bases helped waves of U.S. settlers move into the lands of Native American nations, pushing Indians progressively westward. By 1802, there was a chain of U.S. forts from the Great Lakes to New Orleans.7 Native American groups’ support for Britain in the War of 1812 brought only more displacement, expropriation, and base building.8

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson announced his “Indian removal policy,” aimed at forcing all native groups to give up their lands east of the Mississippi River and relocate to the west. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, was initially supposed to mark the “very western edge of civilization” and the “permanent Indian frontier.” However, by protecting the start of the Santa Fe and Oregon trails, it only furthered the westward migration of Euro-American settlers, miners, traders, and farmers. The Army soon became what one historian has called the “advance agent” and “pry bar” of U.S. conquest.9 A rapidly growing collection of western forts beyond Fort Leavenworth provided more iron for that pry bar and marked the line of westward expansion. By the middle of the nineteenth century, there were sixty major forts west of the Mississippi River and 138 army posts in the western territories.

As Euro-American migration continued, the young nation soon seized more than half of Mexico: some 550,000 square miles of land, including all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, and most of Arizona. It acquired the Oregon Territory from Britain and absorbed the Republic of Texas. In 1853, the Gadsden Purchase added yet more Mexican land, a swath of territory in Arizona and New Mexico larger than today’s entire state of West Virginia. Scores of new Army bases—from Texas’s Fort Bliss to Arizona’s Fort Huachuca, from the Presidio in San Francisco to the Vancouver Barracks in Oregon Country—quickly followed, assisting in the expansion.

With conquest across the continent complete, U.S. bases protected the continuing stream of Euro-Americans heading westward and battled the few remaining unconquered Indian nations.10 Elsewhere, the military established new bases to quell anti-Chinese riots along the construction route for the Union Pacific railroad. When major Native armed resistance ended, the U.S. government began consolidating many of the frontier forts and turned its attention outside the North American continent.11

BEYOND THE CONTINENT

When most people think about the expansion of the United States beyond North America—and the bases that went with that expansion—they generally look to 1898’s Spanish-American War. Again, however, expansion beyond the continent and the roots of our base nation go back much farther. During 1798’s Quasi-War with France, for instance, a hundred years before the Spanish-American conflict, U.S. Navy frigates operated from ports on several Caribbean islands. The Barbary Wars of 1801–5 and 1815 likewise saw U.S. Marines capture and temporarily occupy the fortress and port of Derna (marking the first U.S. occupation of Middle Eastern lands). Through the mid-nineteenth century, the U.S. Navy used temporary bases to support military operations around the globe, in Taiwan, Uruguay, Japan, Holland, Mexico, Ecuador, China, Panama, and Korea.12

Even more significant than these temporary outposts were fleet stations that the Navy established in key strategic locations across five continents after the end of the War of 1812.13 These patrol bases appeared at ports in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; in Valparaiso, Chile, and Luanda, Angola; in Magdalena Bay, Mexico, and Panama City, Panama; on Portugal’s Cape Verde and Spain’s Balearic Islands; and in Hong Kong and Macau. The bases were positioned, as two prominent military analysts explain, “close to the ‘nexus of US security and economic interests,’ namely, important overseas markets.”14 While these modest “leasehold bases” generally supported relatively small fleets and used rented warehouse and repair facilities, they reflected and foreshadowed U.S. aspirations to global power.

These aspirations became clearer with the start of a “pivot” toward Asia: not the much-discussed recent effort by the Obama administration, but its original, pre–Civil War antecedent. In 1842, President John Tyler grew interested in establishing Pacific naval bases, and within two years, the country had opened up five Chinese ports to U.S. trade and military forces with the help of one of the many European and American “unequal treaties” imposed on China. Two base experts explain that although the treaties did not officially create bases, “they guaranteed forward access to US naval vessels, and enabled the Navy to purchase and establish warehouse facilities in any” of the ports. In total, the Tyler administration opened sixty-nine ports to U.S. military forces and trade.15

Commodore Matthew Perry accomplished much the same in Japan and Okinawa (which was then an independent kingdom) a century before their post–World War II occupation. In 1853, for fifty dollars, Perry purchased a plot of land on the island now known as Chi Chi Jima, near Iwo Jima in the western Pacific. He wanted the island to become a U.S. coaling station—necessary for new steam-powered military and commercial steamship travel operations. Perry also created the first U.S. military base in Okinawa. Although it lasted only a year, Perry used the base to help create additional U.S. enclaves and impose favorable treaties on Okinawa and Japan.16 After the Civil War, U.S. officials further increased the nation’s Pacific presence and power by claiming and annexing Jarvis, Baker, Howland’s, and Midway Islands to mine guano deposits and serve as coaling stations.17

The purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867 led to the occupation of a former indigenous Tlingit and Russian fort in Sitka and the establishment of four more bases in the new territory along the northern edge of Asia.18 By 1888, the United States had signed agreements to lease naval stations in the Kingdom of Samoa and in the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Pearl Harbor. After the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893, the United States annexed the islands of Hawaii in 1898 and the newly renamed American Samoa in 1899. Naval bases appeared almost immediately.19

Meanwhile, in 1898 the United States declared war on Spain after the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine provided a pretext for intervening in Cuban efforts to win independence from the Spanish empire. The Navy decided that Cuba’s Guantánamo Bay would make a good naval coaling station. Occupation of the bay helped U.S. forces seize control of the island and install a government to American liking. Others also saw the long-term advantages of Guantánamo: the New York Times declared, “the fine harbor there will make a good American base.”20 From Guantánamo Bay, the military launched its invasion of Puerto Rico, soon annexing that island and the Philippines, Guam, and Wake Island thousands of miles off in the Pacific.21

In 1903, U.S. officials pressured Cuban leaders into accepting thinly disguised U.S. rule in exchange for Cuba’s official independence and the withdrawal of most (though not all) U.S. troops. The U.S.-penned Platt Amendment allowed the United States to invade Cuba at will to ensure stability and so-called independence, prevented Cuba from making treaties with other governments, and permitted the construction of U.S. “coaling or naval stations.”22 The two governments also signed a lease giving the U.S. military “complete jurisdiction and control” over forty-five square miles of Guantánamo Bay—an area bigger than Washington, D.C. Tellingly, the “lease” had no termination date, which effectively meant that Cuba had ceded the territory to its northern neighbor. In exchange, the United States agreed to build a fence, prevent commercial or industrial activities within the base, and pay a meager yearly fee of $2,000.*23

Cuban leaders would eventually annul the Platt Amendment, but U.S. officials insisted on a new treaty to hold on to Guantánamo Bay. The treaty continued the terms of the original lease and stipulated that Cuba could never force the United States to leave. Renters everywhere only wish they had such eviction-proof leases.24

By the end of the nineteenth century, the United States thus had a collection of overseas bases matched in size and global scope by only a few European colonial powers. This base network pales in comparison to what would emerge from World War II. But in displaying American leaders’ ambitions for further economic, political, and military power, it presaged the base nation to come.25

FROM PANAMA TO SHANGHAI

One of the leaders responsible for the expansion of nineteenth-century bases outside North America was the man who came to be known as the “prophet” of the U.S. Navy, Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan. A historian of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Anglo-French competition for global preeminence, Mahan argued that great powers require strong navies capable of protecting a country’s commercial shipping and opening foreign markets to trade. And to have a strong navy, he held, a country needed a far-flung network of support bases. Under his influence, Navy officials pushed for the creation of ever more coaling and repair stations.26 In 1900, Navy warships steamed westward to crush the Boxer Rebellion and further open Chinese markets to U.S. businesses. Soon the U.S. Navy, which had become the world’s second largest, established regular patrols from bases in Hong Kong, Hankow, and Shanghai.27

In 1903, the same year U.S. officials secured access to Guantánamo Bay, they did much the same in Panama. A treaty imposed on the newly independent country gave the United States what amounted to sovereign rights in perpetuity across 553 square miles that became the Panama Canal Zone. The treaty also authorized other extensive powers, including land expropriation outside the Canal Zone and the authority to build bases. Panama would eventually host fourteen. As in Cuba, Panama’s constitution allowed the United States to intervene militarily, and between 1856 and 1989, the U.S. military invaded twenty-four times.28 With prominent U.S. bases occupying their land and enabling easy intervention, Panama and Cuba were effectively colonies.29

Elsewhere in Latin America, the military continued its pattern of intervention. In Nicaragua, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic, U.S. troops were active on an almost yearly basis.30 Each of these interventions and the often years-long occupations that followed involved the creation of bases for occupying American troops. Nicaragua alone, for instance, had at least eight U.S. garrisons stationed on its land between 1930 and 1932.31

Still, at the end of these Latin American occupations, the U.S. military packed up and went home. The same was true at the end of World War I, when the military closed its bases at war’s end and brought hundreds of thousands of U.S. troops home (only in the U.S. Virgin Islands, bought from Denmark in 1917, did the military leave a small submarine base and communication outpost).

When the next world war came along, however, there would be no going home after the war. This time, the bases would stay.

A NATION TRANSFORMED

Even before World War II started, Roosevelt wanted to use far-flung bases to harness the newfound power of long-distance aircraft as an implicit threat to other powers and protection for the country. As early as 1939—before the destroyers-for-bases deal with Britain—Roosevelt expressed interest in obtaining new island bases in the Caribbean. After the war started, he pushed his military leaders to develop plans for a postwar network of military bases around the globe that could ensure U.S. dominance.32 At Roosevelt’s direction, military officials began preparing for the postwar period in November 1941, before the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into the war. By 1943, a Joint Chiefs of Staff paper declared that “adequate bases, owned or controlled by the United States, are essential and their acquisition and development must be considered as amongst our primary war aims.”33

Once the United States entered World War II, the military worked to expand its base collection as quickly as possible. The government signed new deals to station U.S. forces in location after location: new bases were built or occupied in Mexico, Brazil, Panama, Northern Ireland, Iceland, Danish Greenland, Australia, Haiti, Cuba, Kenya, Senegal, Dutch Suriname, British and French Guiana, the Portuguese Azores, the Galápagos Islands, Britain’s Ascension Island in the South Atlantic, and Palmyra Island near Hawaii.34 By war’s end, the military was building base facilities at an average rate of 112 a month. In five years, it built the largest collection of bases in world history.35

Importantly, achieving military dominance was not the only motivation for the growing number of bases. American leaders were also guided by political and economic considerations. Looking forward to what many assumed would be massive postwar growth in international air travel, Roosevelt and other officials were intent on supporting U.S. commercial airlines. They saw this as critical to ensuring U.S. economic dominance not just in the airline industry but also in accessing worldwide natural resources, international markets, and investment opportunities.36 In 1943, for instance, the president sent a survey team to French-controlled islands in Polynesia to make plans for postwar bases and commercial airports connecting North America and Australia. Roosevelt wanted to determine what islands “promise to be of value as commercial airports in the future.”37

Commercial and military planning often went hand in hand. Before the war, for example, Pan American Airways secretly acquired basing rights for the military throughout Latin America. It eventually built and improved forty-eight land and seaplane bases ranging from the Dominican Republic to Paraguay and Bolivia.38 Pan Am thus provided the military with the foundation for rapidly expandable bases to use in the event of war. At the same time, Pan Am also provided itself and other U.S. airlines with the foundation for a significant competitive advantage after the war. The Joint Chiefs likewise saw that investments in overseas bases would provide powerful bargaining chips to obtain postwar commercial air rights. In this way, military and civilian planners pursued the development of bases and air routes that could serve both goals simultaneously.39

“Both for international military purposes and for commercial purposes the Northern, Central, and Southern trans-Atlantic routes should be completed and maintained,” stated a Joint Chiefs of Staff study. “Present air routes to the South-West Pacific should be maintained and developed for military and commercial purposes.”40 As the base expert and retired Air Force colonel Elliott V. Converse explains, “From the beginning of the postwar planning process, [officials] hoped to integrate military and civil airfields into a vast network, assuring both physical and economic security for the United States.”41

At the war’s end, a partially completed base in Dharan, Saudi Arabia, illustrated the link between bases and economic interests, foreshadowing decades of Middle Eastern intervention to come. By June 1945, Germany had surrendered, and the military had determined that there was no need to use Dharan for the war against Japan. Still, the secretaries of war, state, and the navy pushed to continue construction at the site, arguing that “immediate construction of this field used initially for military purposes and ultimately for civil aviation would be a strong showing of American interest in Saudi Arabia and thus tend to strengthen the political integrity of that country where vast oil reserves now are in American hands.”42

Shortly before the war’s conclusion, President Harry Truman addressed the issue of postwar bases during the “Big Three” meeting in Potsdam, Germany. “Though the United States wants no profit or selfish advantage out of this war,” Truman declared, “we are going to maintain the military bases necessary for the complete protection of our interests and of world peace.”

And, he added pointedly, “Bases which our military experts deem to be essential for our protection we will acquire.”43

“A PERMANENTLY MOBILIZED FORCE”

As World War II ended, the United States, like other world powers throughout history, was reluctant to give up what many considered the “spoils of war.” Even if the military had little interest in using a base or a territory, many military leaders felt the United States should not cede its acquisitions. As justification, they generally invoked two military principles. The first, “redundancy,” says it’s always good to have backups. The second, “strategic denial,” says it’s smart to hold on to bases and territories simply to prevent enemies from using them.

The military felt especially justified in retaining captured Pacific islands because of the high human and financial costs of their acquisition. “Having defeated or subordinated its former imperial rivals in the Pacific,” a group of base experts explains, “the United States military was in no mood to hand back occupied real estate.”44 Many in Congress agreed. No one, they felt, “had the right to give away land which had been bought and paid for with American lives.” Louisiana representative F. Edward Hébert explained the logic prevalent after the war: “We fought for them, we’ve got them, we should keep them. They are necessary to our safety. I see no other course.”45

The maintenance of such an extensive collection of military bases was also rooted in a widely held strategic belief that the security of the nation and the prevention of future wars depended on dominating the Pacific through a Mahanian combination of naval forces and island strongholds. “This imperial solution to American anxieties about strategic security in the postwar Pacific exhibited itself,” writes the base expert Hal Friedman, “in a bureaucratic consensus about turning the Pacific Basin into an ‘American lake.’”46

For General Douglas MacArthur, the Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in Japan, and other military leaders, securing the Pacific meant creating an “offshore island perimeter.” The perimeter was to be a line of island bases stretching from north to south across the western Pacific. It would be like a giant wall protecting the United States, with thousands of miles of moat before reaching U.S. shores. “Our line of defense,” MacArthur explained, “runs through the chain of islands fringing the coast of Asia. It starts from the Philippines and continues through the Ryukyu Archipelago, which includes its main bastion, Okinawa. Then it bends back through Japan and the Aleutian Island chain, to Alaska.”47 This plan found support from the architect of early Cold War strategy, the diplomat George Kennan. Kennan saw the island perimeter as equally beneficial for hosting airpower, which would, he thought, allow the control of East Asia without large ground forces.

Eventually, the grandest plans for postwar bases were trumped by concerns about costs and postwar demands for demilitarization. In the Pacific, the military abandoned the offshore island perimeter. Instead, to keep the Pacific an “American lake,” the military would rely on key bases in Okinawa and in mainland Japan, Guam, Hawaii, and Micronesia. To the disappointment of military leaders, after the war, the nation ultimately returned about half its foreign bases.48

Still, the United States maintained what became a “permanent institution” of bases in peacetime.49 In Germany, Italy, Japan, and France, U.S. forces retained occupation rights as a victor nation. After 1947, the military built 241 new bases in Germany, while Japan came to host as many as 3,800 installations.50 The United States signed deals to maintain three of its most important bases, in Greenland, Iceland, and the Portuguese Azores; kept facilities in most of the British territories occupied under the destroyers-for-bases agreement; continued occupying French bases in Morocco; and gained further access to British facilities in Ascension, Bahrain, Guadalcanal, and Tarawa. When Britain wanted to grant complete independence to India and Burma, the U.S. State Department asked its ally to maintain control of three airfields in the former and one in the latter. U.S. bases turned the British Isles into one of several places around the world frequently referred to as an “unsinkable aircraft carrier.”51 Plus, the military enjoyed access to an even wider array of British and French bases still held in their colonies.

Among its own colonial possessions, the United States retained bases on Guam, the Northern Marianas, Samoa, Wake Island, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands, as well as in Guantánamo Bay. When the Philippines gained its independence in 1946, the United States pressured its former colony into granting a ninety-nine-year rent-free lease on twenty-three bases and military installations.

A WORLD OF PERMANENT DANGER

The buildup of U.S. troops around the world was the result of a profound change in how U.S. leaders thought about the very idea of “defense,” as well as a newly expansive concept of “national security.” Even before the United States entered World War II, Roosevelt and other leaders had started developing a vision of the world as intrinsically threatening, in which any instability and danger, no matter how small or how far removed from the United States, was seen as a vital threat. “No attack is so unlikely or impossible that it may be ignored,” argued Roosevelt in 1939. In a world of “permanent danger,” the military thus needed to be a “permanently mobilized force” ready to confront threats wherever they might appear.52 “If the United States is to have any defense,” Roosevelt and others believed, “it must have total defense.”53

In this way, the mentality of the Cold War started to take hold long before the Cold War had even begun.54 After World War II, the result was a machinery of war centered on an expanding national security bureaucracy and a perpetually mobilized military patrolling the globe.55 That the country needed a large collection of bases and hundreds of thousands of troops constantly stationed overseas, as close as possible to any potential enemies, was central to this “forward posture.” A Navy strategic guide explained the first “Requirement of a Forward Strategy”:

U.S. forces are deployed overseas to be in position to engage promptly a hostile threat to the security of U.S. interests or allies. These forward deployed forces are a commitment which reassures our allies and deters the potential aggressor. Additionally, these forces provide a capability for flexible and timely response to other crises and contingencies [i.e., wars].56

While the motivations behind this strategy were diverse, the result was that U.S. bases overseas became a major mechanism of U.S. global power. While the total acreage of territory acquired may have been relatively slight, in the ability to rapidly deploy the U.S. military nearly anywhere on the globe, the basing system represented a dramatic expansion of American might.57

Britain and other European empires had tied their expansionist success to the direct control of foreign lands. For Roosevelt and other leaders, however, wide-scale colonial control was clearly no longer an option. The European powers had already divided most of the world among themselves, and the ideological mood of the time was clearly against colonialism and territorial expansion.58 The allied powers had made World War II a war against the expansionist desires of Germany, Japan, and Italy, and the United States had framed the conflict as an anticolonial struggle, pledging to assist with the decolonization of colonial territories upon war’s end. The subsequent creation of the United Nations enshrined the decolonization process and the right of nations and peoples to self-determination and self-government.

Roosevelt and others saw that the United States would have to exert its power through increasingly subtle and discreet means: the installation of bases as well as periodic displays of military might to keep as much of the world as possible within the rules of an economic and political system favorable to the United States.59 In 1970, a Senate committee found that “by the mid-1960s, the United States was firmly committed to more than forty-three nations by treaty and agreement and had some 375 major foreign military bases and 3,000 minor military facilities spread all over the world, virtually surrounding the Soviet Union and communist China.”60 As the late geographer Neil Smith explains, “global economic access without colonies” was the postwar grand strategy, with “necessary bases around the globe both to protect global economic interests and to restrain any future military belligerence.”61 Alongside U.S. economic and political might, the base network became a major and lasting mechanism of U.S. power, allowing control and influence over swaths of the earth vastly disproportionate to the land actually occupied.

THE CARTER DOCTRINE

During the Korean War, the U.S. military built yet more overseas bases, increasing their number by 40 percent. By 1960, the United States had signed eight mutual defense pacts with forty-two nations, and executive security agreements with more than thirty others, helping it secure base access around the globe. Following some reductions after the Korean War, there was a further 20 percent increase in base sites during the war in Vietnam.62 By the mid-1960s, the United States had some 375 major foreign military bases and 3,000 minor military facilities spread worldwide. The bulk effectively surrounded the Soviet Union and China.63

Through the 1970s, the Middle East remained one of the few regions on Earth to see relatively little Cold War competition and a small U.S. base presence. For the most part, U.S. officials sought to increase American influence in the area by backing and arming the regional powers Israel, Saudi Arabia, and Iran under the shah. But after the Iranian revolution overthrew the shah in early 1979, and the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan in December of that year, the approach changed dramatically. In his January 1980 State of the Union address, President Jimmy Carter announced a policy change that rivaled Roosevelt’s destroyers-for-bases deal in its significance for the nation and the world. Enunciating what became known as the Carter Doctrine, President Carter spoke about the importance of the region “now threatened by Soviet troops.” He warned the Soviet Union and other countries that “an attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America.” He added pointedly, “Such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.”64

Carter soon launched what became one of the greatest base construction efforts in history. The Middle East buildup soon approached the size and scope of the Cold War garrisoning of Western Europe and the profusion of bases built to wage wars in Korea and Vietnam. U.S. bases sprang up in Egypt, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere in the region to host a “Rapid Deployment Force,” which was to stand permanent guard over Middle Eastern petroleum supplies.65 Eventually, the Rapid Deployment Force grew into the U.S. Central Command, a geographic command like those overseeing Europe and the Pacific. The Central Command would soon lead three wars in Iraq and the war in Afghanistan, plus dozens of other military operations.

In the aftermath of the 1991 Gulf War in Iraq, thousands of troops and a significantly expanded base infrastructure remained in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, and Oman. The 2001 and 2003 invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq have led to yet another dramatic expansion of U.S. bases in the region. In the Persian Gulf alone, the U.S. military has built major bases in every country save Iran. Qatar’s al Udeid Air Base has become home to the Central Command’s air operations center for the entire Middle East; Bahrain is now the headquarters for the Navy’s Fifth Fleet and its Middle Eastern operations; and Kuwait has become a particularly important staging area and logistical center for U.S. ground troops. The military has also maintained bases in Jordan and as many as six secret U.S. bases in Israel.66 On a near-permanent basis, the Navy now maintains at least one aircraft carrier strike group—in effect, a huge floating base—in the Persian Gulf itself.

Elsewhere in the greater Middle East, the military has established a collection of at least five drone bases in Pakistan; expanded a critical base in Djibouti, at the strategic chokepoint between the Suez Canal and the Indian Ocean; and created or gained access to bases in Ethiopia, Kenya, and the Seychelles. Even in Saudi Arabia, where widespread anger at the U.S. military presence led to a public withdrawal in 2003, a small U.S. military contingent has remained to train Saudi personnel and keep bases “warm” as potential backups for future conflicts. In recent years, the U.S. military also established a secret drone base in the country.

In Afghanistan, meanwhile, the military will retain at least nine large bases after the official withdrawal of U.S. troops. Although the Pentagon failed in its effort to maintain as many as fifty-eight “enduring” bases in Iraq after the 2011 withdrawal from the country, the fortress-like embassy in Baghdad—the world’s largest—is effectively a base. Base-like State Department installations and a large contingent of U.S. private military contractors have also remained.67 And following the 2014 start of the new war in Iraq and Syria against the Islamic State, thousands of U.S. troops have returned to at least five military bases in Iraq.68

Stepping back, it’s telling that the Carter Doctrine and the bases it spawned persisted despite the disappearance of the Soviet Union and any threat it may arguably have posed to Middle East oil. The U.S. military presence in a region that sits atop the world’s largest concentration of petroleum and natural gas reserves is not a matter of Cold War exigency.69 Rather, as the late base expert Chalmers Johnson explained, since World War II, “the United States has been inexorably acquiring permanent military enclaves whose sole purpose appears to be the domination of one of the most strategically important areas of the world.”70

More broadly still, the Middle East base buildup reflects the continuation of a millennia-old strategy for pursuing power around the world. Like empires from ancient Egypt to imperial Britain, the United States has come to use its foreign bases to assert influence and dominate far-off lands, resources, and markets. But even more than its predecessors, including the empire upon which the sun never set, the United States since World War II has become defined by its unprecedented collection of bases encircling the planet.

Entrance to the world’s largest base exchange (“PX”), at Ramstein Air Base, Germany.