Vroom, vroom, vroooom. A soldier loudly revved the engine on his Dodge Charger muscle car as he waited at the traffic light at the Katterbach Kaserne’s exit gate, seemingly annoyed at the dozen activists standing a few yards away. It was the summer of 2010, and the protesters were taking part in a weekly demonstration outside Katterbach, one of several large bases in Ansbach, Germany. Most were members of a local citizen’s initiative or another activist group called Etz Langt’s, whose name in local Franconian means “It’s Enough.” Many wore white T-shirts with the symbol of their movement: a helicopter inside a red-slash “no” sign. One carried a rainbow peace flag. Others carried posters in German and English with phrases like STOP THE HELICOPTER NOISE, HELICOPTERS TO WIND TURBINES, and, simply, YOU CAN GET OUT.

Fierce resistance to military bases has never been an issue in Okinawa alone. Around the world, the construction of new U.S. bases and the operation of existing ones have increasingly become the subject of protest. This is now true even in countries such as Germany and Italy, which have long been regarded as some of the friendliest and most stable base locations abroad.

Ansbach, a small Bavarian city of about forty thousand, has been a typically supportive home for a significant U.S. presence since World War II. When the Pentagon announced its base transformation plans for Europe, it named Ansbach one of the Army’s seven “enduring communities” in Europe. Since then, the Army’s five major kasernes around Ansbach and surrounding towns have seen a string of major new construction projects. These have included a new town house development, a shopping center, and tens of millions spent on family housing renovations, recreational facilities, and fitness centers.1

At the protest, I asked a social worker, Ann Klose, why she was there. “The noise, first,” she replied. The city’s primary military occupant is one of the Army’s largest aviation brigades, and it flies numerous helicopters, including Apaches, Black Hawks, and large dual-rotor Chinooks.2 One man described living less than five hundred yards from the fence surrounding the Katterbach Kaserne and awaking at night with the sound of helicopters in his ears. “You can’t sleep,” he said. The vibration of the helicopters’ blades makes his kitchen plates rattle. “Whoomp, whoomp, whoomp, whoomp,” he said, imitating the sound. It’s so bad, he added, that many people in his neighborhood have thought of selling their homes. Even though they’re living outside the fences, the helicopters are so loud that sometimes they feel as if they’re living inside the base.

The majority of people in the movement are involved because of the noise, said Klose (a pseudonym). When the helicopters are in Ansbach and training, she explained, many more people come to the protests. When most of the soldiers and helicopters are deployed, as they were during my visit, the protests were smaller. On the curb, a pile of protest signs lay unused.

Klose told me she was also protesting because she believed the local Ansbach administration knew about the Army’s buildup plans but tried to keep them secret from citizens. There was “a kind of conspiracy of silence” between politicians and the media, she said.

And there was more to it, too. Klose was carrying a sign that read NO MORE WAR FROM GERMANY, and she readily acknowledged that her opposition to the base went beyond the helicopter noise and the secrecy around the expansion’s planning. For her, as for others, opposition to the U.S. base presence was rooted to varying degrees in the fact that the United States had invaded Iraq and was waging war from their lands. In Ansbach, Klose and others told me, some of their discomfort comes not so much from the noise itself as from what it represents. The whoomp-whoomp of the whirling blades symbolizes the wars that those helicopters have helped wage, and hosting the helicopters in their city makes the locals feel complicit. For some, there is a painful irony in the garrison’s motto, “We are all part of the fight.”

SIMMERING RESENTMENTS

The army garrison in Vicenza, Italy, is another place where vehement antibase protests have surprised many. Opposition in Italy had long been restricted to small, scattered protests in places such as Naples and Pisa, and a movement against a missile base in Sicily in the 1980s. U.S. officials had long thought of Italy’s wealthy and strongly conservative northeast as a particularly supportive host. But the plans to build a new base at Vicenza’s Dal Molin airport unexpectedly provoked a widespread surge of protest. Equally surprising, the opposition movement was remarkably diverse: it joined self-identified housewives and businessmen, former 1960s radicals and young anarchists, university students and religious organizations, pacifists and disaffected members of the openly racist anti-immigrant Northern League. They formed a sometimes rocky but effective and unusually creative coalition.

While historically Vicenza saw little of the protest found in other communities hosting U.S. bases, there were some long-standing tensions that were largely suppressed until opposition built against Dal Molin. Army officer Fred Glenn remembers that when he arrived in Vicenza shortly after the return of U.S. forces in 1955, most Americans were “standoffish.” Few wanted to live off base, and other than some Italian Americans, “very few bothered to learn the language.” From time to time, Glenn was the officer in charge of payroll for the local workers. When handing cash to the waiting Italians, “We were required to have a pistol highly, highly visible,” he says. “In fact, on the pay table.” He thought the rule was “outrageous.”

As at many other locations, the military presence around Vicenza also distorted the local housing market. When Vicenza native Enzo Ciscato and U.S.-born Annetta Reams started looking for a home as newlyweds in the 1980s, Ciscato remembers, the preference for renting to soldiers’ families was so great that they had trouble finding an apartment. Eventually, a friend introduced them to someone in the housing office of Vicenza’s main base, Caserma Ederle. When the staffer learned that Reams was an American, he said, “Oh that’s great!” Then he told Ciscato to “shut up” when visiting apartments. “Act like a couple of Americans, because if they know you are Italian, they will not rent to you.”

“You can think how great” that felt, Ciscato told me. “As a person born in this town, to go to look for a house in this town, acting [like] an American soldier to be able to have a house.”

Another Vicenza local recalled growing up near the Caserma Ederle during the Cold War and seeing American soldiers all around in the streets and the shops. “It was normal to wake up in the morning when they practiced” their marching cadences, she told me. “We were angry and annoyed,” she said, but people felt they just had to “tolerate it, to be patient … What can you do?”

With such resentment already simmering under the surface, the buildup to the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was a major point of motivation for antibase activists in Vicenza, just as it was in Ansbach and many other parts of the world. Several hundred gathered for protests and marches around the Caserma Ederle. Some attempted to block trains moving military matériel for Ederle-based battalions deploying to Iraq.3

Guido Lanaro was one of the activists involved, and he remembers first hearing rumors about a new base around the same time, in 2003 or 2004. Enzo Ciscato, for his part, first heard alarming talk about the old Dal Molin airport when he was a member of his local neighborhood governing committee. A city council member told the committee there were rumors about “something happening with the Americans.” It was then, Ciscato said, that it “started to smell strange. Because after mentioning something, everything was kept secret.”

NO DAL MOLIN

In May 2006, around the time the Army was asking Congress for Dal Molin construction funding, a Vicenza city official and U.S. military representatives finally presented a detailed plan for the new base to the city council. The presentation came complete with PowerPoint slides, documents, maps, and pictorial renderings, and for many it confirmed suspicions that the mayor and the city council had known about the project for some time. Many believed that it was “deliberately hidden from the citizenry,” Lanaro said.4

Reams remembers the same feeling: people felt that “their rights were being taken away” by the politicians and secret agreements. “They say, ‘Here is a present for you. And what you have to say doesn’t matter. Take it whether you like it or not.’”

Beyond feeling excluded from the decision-making process, many in Vicenza grew increasingly concerned as details about the base emerged. The new base was set to take over 135 acres at the Dal Molin airport and a large adjacent grassy field; many feared it would destroy one of Vicenza’s last areas of green space. Environmental scientists and engineers showed that the military’s plan to drive hundreds of pylons into the ground to support the buildings’ foundations risked puncturing the city’s aquifer and its main source of drinking water, in addition to causing other environmental damage. Many were afraid that the base would harm the internationally famous architectural and cultural fabric of the city while increasing traffic in an already congested town by bringing in thousands of new soldiers and family members. Given the critical role the 173rd brigade played in the fighting in Afghanistan and Iraq, people also worried that returning soldiers would bring the trauma of war back to Vicenza; many pointed to the case of a soldier who brutally raped a sex worker after returning from an Iraq deployment and successfully gained a reduction in his sentence because of the “prolonged psychological stress” he had experienced at war.5

Ciscato points out that the nature of the U.S. presence in Vicenza has changed since the Cold War. In those days, he says, the Italian bases were strategically positioned to defend “against Russian invaders,” but now “it is an operative site. People from here—they don’t stay here … They go to war and come back. They bring their damages back. They rest. They go to war again.” Now, he said, “We’re talking about combat units being here. It’s a bit different.”

The official announcement of the plan for Dal Molin led to increasingly large protests against the base. A little more than a month after the city council presentation, hundreds blocked the airport’s entrance for hours. Later that summer, thousands peacefully occupied the Basilica Palladiana, one of Vicenza’s central landmarks, for twenty-four hours, talking through the night on its steps and draping NO DAL MOLIN banners and giant peace flags from the arched balconies. It was a struggle “for dignity,” one of the protesters said to me. “Not to be part of a city where soldiers live to go around the world and kill people. I don’t like this … When someone asks me, ‘Where do you live?’ I want to be proud to say, ‘I live in Vicenza: a beautiful city.’” She paused. “But now, I’m not so proud. Because [when] everybody speaks of Vicenza, of the military base—it’s not good for our image in the world.”

Soon, the No Dal Molin activists also built their own base, which they called the Presidio—a headquarters for the movement, adjacent to the Dal Molin construction site.6 Beginning as a trailer parked in a cornfield, over time it grew to include two large tents and three shipping containers, with a full-scale kitchen, storage, and toilets. Starting in 2007, No Dal Molin members occupied the Presidio around the clock for more than two years, making a permanent encampment and permanent protest against the base. The Presidio became a kind of community center, a common ground where people could meet and connect with people from diverse political and social backgrounds. The Presidio was more than a movement headquarters. It became, as Guido Lanaro put it, “like a second home.”

Thanks to the Presidio’s creation and continuing protests, the largest of which drew an estimated hundred thousand people in a city with just 115,000 inhabitants, No Dal Molin gained national and international attention.7 “We felt so powerful,” Marco Palma, a No Dal Molin spokesperson, told me. “We felt it was impossible that the base could be built. Because when you have so much energy from so many people, we felt like we could do anything in the world.”

BASE ECONOMICS

In communities like Ansbach and Vicenza, public opinion about the base presence is often divided. When the Dal Molin plan went before the Vicenza City Council, twenty-one center-right allies of Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s party overcame the votes of seventeen center-left coalition members. Around this time, the city’s major newspaper—whose controlling interest belongs to the equivalent of the city’s Chamber of Commerce—began running stories suggesting that the U.S. military would close the Caserma Ederle if prevented from building at Dal Molin. FROM EDERLE A DESPERATE SOS: “SAVE OUR JOBS,” read one headline. The reports fueled fears that rejecting the base would damage the local economy.

To support the base plan, one Italian Caserma Ederle employee, Roberto Cattaneo, formed the Yes to Dal Molin Committee. The new base, the Yes Committee’s website said, was “offering with it an opportunity for economic and occupational development for the city and for all the surrounding areas.” The committee cited total economic benefits of more than €1.5 billion from construction at Dal Molin.8

The suggestion from base supporters in Vicenza that rejecting construction at Dal Molin would damage the local economy is a frequent theme in debates over U.S. bases. When I was watching the protest outside the Katterbach Kaserne in Ansbach, I struck up a conversation with two of the gate guards. Both lived locally and worked for a company contracted to provide security for Army bases in Bavaria. One of the guards acknowledged that the noise is indeed loud and helicopters fly very low over the neighborhood. But Ansbach depends on the bases economically, he said.

This is a common perception. In Germany and other countries around the world, bases are widely regarded as an economic boon, just as they are in communities in the United States. And, indeed, bases do enrich some local communities.* The “golden years” in places like Baumholder show us as much. After all, U.S. taxpayers spend tens of billions of dollars every year to maintain bases and troops overseas. All that money has to go somewhere.

However, research about the economic effects of bases in Germany, the United States, and elsewhere consistently shows that the economic benefits of bases are less significant than one might expect. The benefits are enjoyed disproportionately by relatively few individuals and industries, and people tend to ignore a variety of costs associated with bases that significantly decrease their net economic impact. Moreover, bases are an inefficient form of economic investment; often, they actually inhibit more productive and profitable forms of economic activity. Okinawa, for example, remains Japan’s poorest prefecture. The causes of that poverty are complex, but the period of formal U.S. occupation of Okinawa that lasted until 1972 clearly inhibited economic growth. In recent years, as the base presence has declined, Okinawa’s economy has expanded and diversified around tourism, IT, call centers, and logistics.9

Baumholder also shows how the golden years often fade. As the dollar weakened relative to the mark, soldiers’ economic impact declined. Meanwhile, with the West German “economic miracle” taking off in the late 1950s, better jobs—especially for women—appeared than those available on and around the bases. Often, most on-base jobs available to locals are relatively low-skill, low-wage positions, such as janitorial and landscaping staff. Other off-base employment supported in part by a base presence appears in the service sector or the construction and industrial trades, but the vast majority of higher-skill, higher-wage jobs go to U.S. military personnel and U.S. civilians. From the perspective of the local community, most of the people working on foreign bases are, of course, foreigners—so bases offer far fewer jobs than their sprawling size might suggest.10

Bases also tend to occupy valuable land that could be used in other ways. This has been especially true in German cities such as Heidelberg, Würzburg, and Berlin, in densely urbanized Japan, and in the middle of downtown Seoul. Bases also occupy thousands of acres of precious beachfront property in places such as Okinawa, Guam, and Diego Garcia.

In recent decades, the economic impact of U.S. bases has also declined as bases have become increasingly self-sufficient and isolated from local economies. Bases like Ramstein, with their plentiful food outlets, entertainment, and shopping, mean that troops and their families almost never have to leave base. In turn, this means most of their money never reaches the local economy.

Spending by troops is only part of the story, of course. As we have seen, most U.S. taxpayer money goes to construction, the procurement of goods, and the daily operation, maintenance, and repair of bases. In Germany, some of these U.S. contracts go to German companies—but many do not. Instead, they often go to U.S.-based firms. (For fiscal year 2015, Congress placed significant restrictions on awarding large contracts to foreign companies.)11 Sometimes U.S. firms subcontract to local businesses, but in either case, the vast majority of contract dollars goes to large corporations. As we have seen, out of an estimated $385 billion the Pentagon paid between 2001 and 2013 to private companies for work done abroad, about one third went to the top ten recipients—companies like former Halliburton subsidiary KBR and other major military contractors such as DynCorp, ITT/Exelis, and the oil giant BP. This means that much of the money generated by bases flows out of local communities to company headquarters (and, not infrequently, to various offshore banking havens). The trend is particularly pronounced in Okinawa, where much of the money flowing from the U.S. presence has gone to Tokyo-based construction companies rather than Okinawan businesses.

Among locals who do benefit from foreign bases’ presence, some of the most advantaged are those involved in real estate. The Pentagon pays for the housing of U.S. military personnel, and it pays generously—often well above market rates. Property owners, real estate developers, land speculators, real estate agents, and construction companies often enjoy large profits as a result. An Italian base employee described in a letter how military housing allowances are “in most cases significantly more than locals can spend on rent,” which makes Americans “a most welcome and cherished community on the demand side of the real estate market.” The employee noted that since Americans pay higher rents, landlords “have, in the course of time, started to plan and build houses and homes specifically designed for Americans … In some communities entire streets or new construction projects are leased out to Americans.” As a result, local renters can find themselves priced out of their own communities.12 Locals also don’t come with the financial security of the U.S. government paying their bills. As the Vicenza-based anthropologist Guido Lanaro explained, it’s “very convenient to rent to the Americans because you are one hundred percent sure that the rent will be paid.”

Smaller amounts of base money tend to flow into local service industries such as restaurants, bars, and taxis. The German base expert Elsa Rassbach pointed out to me that taxi drivers have been very supportive of U.S. bases in places like Ansbach because the military often pays for expensive rides between towns in the area. I asked Rassbach if she thought this was deliberate. “Absolutely,” she replied. “It’s community relations.”

When locals focus on bases’ perceived economic benefits, they also often overlook bases’ costs, which can be less visible. For instance, host countries usually provide land without requiring the United States to pay rent or taxes on it. Whether people know it or not, that’s a subsidy provided by local governments and their citizens. Host countries have also financially supported U.S. bases for decades through “burden-sharing,” “sympathy payments,” and, increasingly, through in-kind contributions. (These include the provision of security in Germany and other countries; base construction in several Persian Gulf nations; and the free use of buildings and training ranges in Italy.) In 2004, the Pentagon calculated host countries’ in-kind contributions at $4.3 billion, in addition to billions more in direct burden-sharing payments.13

WHEN BASES CLOSE

The most illuminating perspective on the economic impact of bases comes from studies of what happens when bases close. In communities threatened with base closures, locals often fear dire consequences. Andy Hoehn, one of the senior U.S. officials sent to Germany to discuss a “very significant drawdown” of forces as part of the Bush administration’s global base realignment, recalls local politicians in Rheinland-Pfalz, Bavaria, and other states with large base concentrations pleading that their areas be spared the cuts. Hoehn was somewhat surprised to note “their appeals to us were really … of culture and economy, and not of security. They were not there to make an argument that there were security reasons for a large number of troops to remain in Germany in 2004.” Instead, the politicians simply insisted that “our local economies depend upon the presence of these troops.”

“And not only were they appealing to us,” Hoehn explained, “but they were positioning among each other. So it was, ‘At least don’t leave my region … If you’ve got to do it over there, that’s okay. But just don’t leave here.’” He added, “It was emotional. It was a plea. They were pleading. This was a plea to us not to leave.”

Given the politicized nature of base closures, it’s not surprising that some of the early research into the effects of U.S. base closures was often politicized as well.14 But more recent research from around the globe is coming to a clear conclusion: while communities often anticipate that base closures will cause catastrophic economic damage, generally the impact is relatively limited and in some cases actually positive. In the cases where communities do suffer intense economic harm, most tend to rebound within a few years’ time.

In Germany, the Bonn International Center for Conversion conducted an authoritative study of U.S. base closings after the Cold War, primarily using the Pentagon’s own data. It showed that between 1991 and 1995, the U.S. military returned around a hundred thousand acres of base land to the German government and withdrew 75 percent of its forces, or almost two hundred thousand troops.15 Annual U.S. military spending in Germany dropped by around $3 billion. Because most U.S. troops have been concentrated in Rheinland-Pfalz, Bavaria, and three other states in southern Germany, some regions and communities where U.S. troops were based were “seriously impacted” by the drawdown. Across the country, although 34,500 Germans lost civilian jobs, representing about 0.04 percent of the country’s population and 1 percent of the labor force, the study found, the closures and reductions had no “significant effect on Germany’s economy as a whole.”16

A more recent study of the German military’s own base closures in 298 communities in Germany between 2003 and 2007 showed that “negative impacts of base closures” were “non-existent.” Specifically, there was “no significant impact on the economic development of the communities around a base as measured by household income, regional output, the unemployment rate, and revenues from the value-added tax (VAT) and income tax.” While U.S. bases in both Germany and the United States tend to be larger and more integrated into local communities than German bases are, these results are striking. The authors hypothesize that the speed with which local communities converted former bases into other uses such as hospitals and tourist attractions may have helped to offset any negative effects.17 German communities facing the closure of U.S. bases have undertaken similar conversion efforts, creating schools, housing, offices, and retail space. In Ansbach, for example, after the Army returned the Hindenburg Kaserne, the city transformed the base into the Ansbach University of Applied Sciences, plus a shopping mall and office space.18

In the United States, research on the impact of base closures has produced similar findings. A review of sophisticated broad-based econometric studies showed an “unambiguous” conclusion: “Base closures had either no significant regional impact or a small impact that quickly vanishes with time.”19 The result was corroborated by a study of the effects of the Swedish military’s closure of bases in Sweden.20

Focusing more specifically on the jobs question, a Government Accountability Office study showed that the majority of communities affected by closures did not experience rising unemployment.21 A Congressional Research Service study actually found a drop in unemployment rates in communities where bases closed compared to the national average. A 1998 Pentagon study found that only 14 percent of federally employed civilians eligible to claim unemployment insurance following a base closure actually claimed it, suggesting they found other jobs or left the workforce. A study of 3,092 counties and 963 domestic base sites over twenty years also contradicted “doom and gloom” predictions about job losses. It showed instead that closure had a positive impact on employment after only two years, perhaps because of government conversion assistance and “community optimism (following apprehension).” In short, the study concluded, the long-run impacts of base job reductions are “overall positive.”22

The experience in Okinawa further confirms much of the research. The closure of an Army base, for example, provided seaside land for the creation of an entertainment and shopping area, which now employs about three thousand people and attracts around a million visitors annually. A 2007 study found that the area’s impact on the local economy was about 215 times that of the base. Another study has shown that a shopping mall and office complex in the Okinawan capital, Naha, has sixteen times the economic benefit of the military housing formerly occupying the site.23

Such findings should not be surprising: “bases are not corporations that accumulate capital and contribute to the growth of the local economy,” explains the Okinawa International University economist Moritake Tomikawa. Having land resources occupied by U.S. bases, he says, “is a huge economic loss for the prefecture.” With the military gradually returning base land, economists expect Okinawa’s diversifying economy to grow faster than that of any of Japan’s other prefectures.24

TRUE DEMOCRACY?

Such positive statistics are often little known, and in Vicenza most local base supporters, along with U.S. military officials, tended to portray the No Dal Molin movement as a small minority in town. The No Dal Molin activists tended to say the same about the size of the Yes movement, while acknowledging the power of the business interests, politicians, and government officials supporting the base. An October 2006 survey by a prominent Italian political scientist found that 61 percent of Vicenza residents opposed the base, while 85 percent supported a referendum to decide the plan’s fate.25 In 2008, it appeared this wish would come true: in response to a lawsuit brought by base opponents, a regional court ordered work on the base suspended and decreed a local referendum to decide Dal Molin’s fate.26 The court found the government’s approval of the plan on the basis of nothing more than a verbal agreement to be “absolutely incompatible” with the law.27

Italian courts are notoriously slow. Across Italy, there are around nine million cases awaiting appeal.28 And yet, in the Dal Molin case, the Berlusconi government appealed the regional court’s ruling directly to Italy’s highest court and won a judgment within forty days. Invoking the secret 1954 bilateral agreement with the United States and a Mussolini-era law from 1924, the justices said the lower court lacked jurisdiction over decisions about a base, since such decisions are essentially a political question.29 On the basis of the ruling, another Italian court suspended the local referendum four days before the vote.

In a show of defiance, however, local volunteers held their own referendum. With the help of Vicenza mayor Achile Variati and strictly following election rules, almost 25,000 participated. Ninety-five percent voted against the base.30 Buoyed by the results, protests continued. In early 2009, hundreds of protesters cut through the fence to Dal Molin and created a “Peace Park” there, occupying part of the construction site for three bitterly cold and snowy days in January.

Days later, the Italian and U.S. governments announced final approval for the base. In the months that followed, more than a dozen construction cranes rose around the site, visible from miles around.

When I toured the mostly completed Dal Molin base in 2013, an Italian civilian working for the Army said, “I loved this project from the very beginning.” She and a U.S. colleague, both of whom asked not to be named, had little interest in the protesters. She described the Presidio as a “gypsy camp,” while he saw the protesters’ actions as mostly “vandalism.” (At one point, when No Dal Molin activists discovered new fiber optic cables laid without proper authorization near Dal Molin, around a hundred people dressed as utility workers gathered on the street and sealed the access points to the cables with concrete.31) “They tried all the protests they could try,” the American said, but he thought the majority of the community didn’t care. Anyway, he added, “a local protest won’t change the direction of national policy.”

Traditional political science would typically agree with this assessment. Many political scientists would say that local protest should generally be irrelevant in such a situation. Even if a majority of Vicenza residents opposed the base, even if a newly elected mayor and city council rejected the plan (as they did in late 2008), decisions about military matters and other issues of foreign policy should be made not by local authorities but by nationally elected politicians. And in this case, the Italian government approved the base.32 Many would suggest that this was democracy at work. Some might point to the U.S. base in Manta, Ecuador, as a telling comparison: in that case, the majority of locals supported the base, but the national government opposed it, and the base was eventually removed.33

Still, many in Vicenza ask how democratic the decision to build the Dal Molin base really was if the presence of U.S. bases in Italy rests on a secret 1954 agreement approved without the consent of the Italian parliament or the U.S. Congress. They ask whether the decision was really democratic if Italian and U.S. officials carried out their Dal Molin negotiations in secret, preventing any public debate at either the national or local level until after they had made an initial agreement. They ask whether a real democratic decision would violate Italian and European contract bidding regulations, as a regional court found. They ask whether a democratic decision would bypass an environmental impact assessment planned by the Ministry of the Environment, which the court also determined was required under national law. (In a leaked letter, a special commissioner responsible for overseeing the project acknowledged the environmental danger posed by the base and discussed ways to circumvent the environmental assessment because of its potential to “put the final decision in jeopardy.”34) And how truly democratic was it, many in Vicenza ask, if a foreign power—the United States—exerted what appears to be significant pressure on the Italian government to follow through with the agreement, regardless of what Italians really wanted?35

A DIVERSITY OF MOVEMENTS

Though the No Dal Molin movement failed to stop the construction of the new base in Vicenza, it did win a concession. The U.S. military agreed to move the base from its originally planned location at the civilian airport on the east side of the Dal Molin site to a former Italian Air Force base on the site’s west side. The mayor declared the eastern half would be a permanent “Peace Park,” although the city hasn’t decided yet what it will look like. The antibase activists themselves are divided about what this park represents. Several neighborhood associations, who see the entire Dal Molin site as space stolen from Vicenza’s people, regard the park as a reminder of the movement’s defeat. Others see it as a tangible victory, a “beautiful space,” and “a peaceful provocation” to the new base—a way of constantly reminding the soldiers that there is another way to live, one that does not revolve around making war.

Enzo Ciscato was among those skeptical of the park. It couldn’t be a site “where you go to relax,” he said. Watching the base’s construction and knowing it was causing “irreversible” damage had made him “feel sick.” At best, Ciscato said, he hoped the Peace Park could become a center for learning about militarization and the harms of war, a place where people go to transform anger about the base into something positive for the community.

Guido Lanaro agreed that building a “documentation center” about militarization and military bases would be “the best way to keep alive the spirit of the Presidio.” Perhaps, he said, the park could be home to a new kind of Presidio that might help other movements stop bases from being built elsewhere.

For some in the No Dal Molin movement, perhaps there was a small consolation when the Army announced in 2013 that—contrary to the stated reason for the base construction—it was not going to consolidate the 173rd Airborne Brigade at Dal Molin after all. Ultimately, the movement was right: there was little need for the new base.

Like No Dal Molin, movements worldwide have achieved mixed results in their efforts to stop the construction of new bases, to close existing bases, or to change how bases and troops affect their countries and communities. The victories and defeats are not always clear-cut. In Okinawa, for example, protesters have failed to remove the Futenma base, but they have dramatically slowed the creation of a new Marine Corps base in Henoko, which now may never get built.

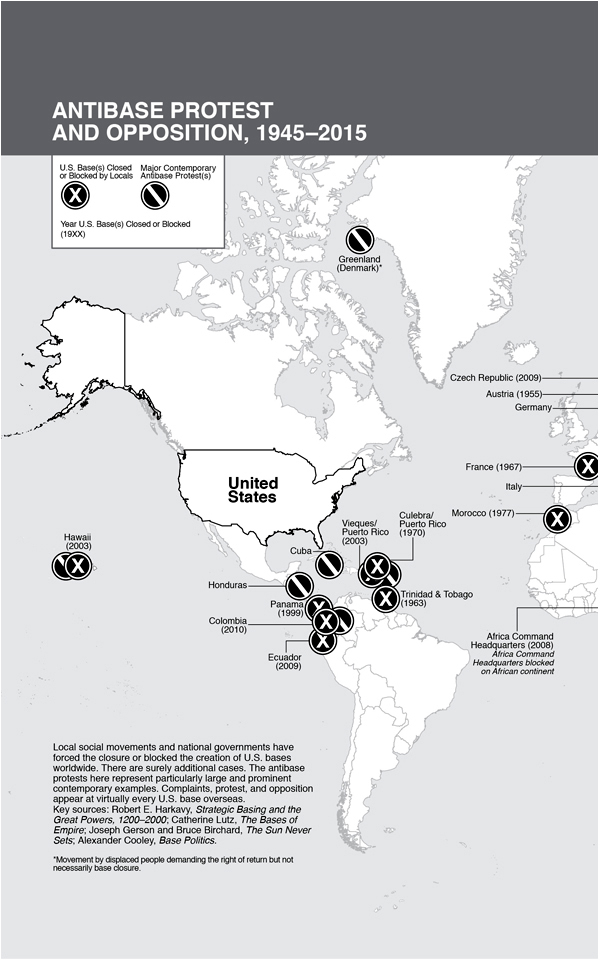

Elsewhere, movements led by ordinary citizens and politicians alike have closed or blocked bases or won significant concessions from U.S. forces over the decades. In the aftermath of World War II, U.S. troops (along with Soviet and other foreign forces) were forced to withdraw from bases in Austria as part of the declaration of Austrian neutrality, which included a constitutional ban on foreign bases. Newly independent, decolonized nations such as Morocco, Trinidad, and Libya forced the closure of bases during the 1960s. In 1966, Charles de Gaulle ended most of France’s involvement in NATO and ordered the removal of U.S. bases within a year’s time. American bases were the source of major controversy in Turkey throughout the 1960s and 1970s, prompting major protests, strikes by base employees, and bombings and kidnappings by extremists; in 1975, U.S. troops withdrew from all but two bases there.36 Elsewhere during these turbulent decades, the military was forced to vacate some of its bases in Japan, Taiwan, Ethiopia, and Iran.

Following the 1986 overthrow of the U.S.-backed regime of Ferdinand Marcos and the creation of a new constitution banning foreign bases, the Philippines famously refused to renew the lease on U.S. bases in the country. Not long after the volcanic eruption of Mount Pinatubo badly damaged Clark Air Base in 1991, U.S. bases and troops were gone.37 By decade’s end, the military also vacated its bases in Panama as part of the termination of the Panama Canal Zone Treaty.

In 2003, Hawaii persuaded the Navy to return Kahoolawe Island, home to important sacred sites for native Hawaiians.38 The people of Puerto Rico accomplished the same task that year with the island of Vieques, pushing the Navy off their land with the help of a major movement of peaceful civil disobedience. In contrast, U.S. forces also officially withdrew from Saudi Arabia in 2003 in the aftermath of al-Qaeda’s Khobar Towers bombing and the September 11, 2001, attacks (though some bases and troops have quietly remained). In 2009, the government of Ecuador refused to renew the lease on the base at Manta. And in one of the most remarkable evictions in recent years, the Iraqi parliament refused to allow the United States to retain bases and troops in the country after the end of the U.S. occupation, despite the Pentagon’s desire to maintain as many as fifty-eight “enduring” bases in Iraq (some troops never left; the arrival of new troops to fight the Islamic State in 2014 saw a return to at least five bases).39

A glance at this list—spanning de Gaullists and anticolonial nationalists, indigenous activists and violent extremists—suggests the diversity of the motivations behind base movements. Within countries, territories, and communities where bases are located, there are often multiple movements with different aims and tactics. Within movements, too, there is often considerable diversity of opinion about aims and tactics. Far from all the movements seek the removal of U.S. bases. A number of movements in Hawaii, Guam, Okinawa, and Germany, for instance, are only asking for the reduction of aircraft noise or greater environmental protection during training exercises. Most Chagossians are not calling for the removal of the base on Diego Garcia, just the right to return to their islands and proper compensation for their exile; in fact, many would like the opportunity to work on the base.

In many movements worldwide, protesters go to great lengths to emphasize that their opposition is not motivated by anti-Americanism. During a huge national demonstration in Vicenza, members of a Rome-based group called Americans for Peace and Justice were overwhelmed with support. “We could hardly move because everyone kept stopping us to applaud and take our pictures,” Stephanie Westbrook recounted. “People were hugging and kissing us, giving us flowers and glasses of wine. It was an extraordinary outpouring of love and sympathy.”40

After the demonstration, Gina Masi, a local seventeen-year-old dressed like a punk in black and spiked metal, approached one Yankee who had joined the protest. Masi was in tears. “Please tell your people that we are not anti-American!” she said. “Look at me. My clothes are American, the music I love is American. Even my boots are American Eagle. But we want to relate to Americans through culture and music, not military bases and war.”41

Desert training outside Camp Lemonnier, Djibouti.