The lack of full democracy in Guam and other places where one finds U.S. bases overseas is only the beginning. In their quest to secure base access around the globe, government officials have repeatedly collaborated with murderous, antidemocratic regimes and ignored widespread evidence of human rights abuses. The history of U.S. involvement in Honduras—where the “temporary but indefinite” Soto Cano Air Base has been operating since the 1980s—dramatically demonstrates just how much the military’s actions contradict the very ideals that it is supposedly dedicated to protecting.

The passions surrounding the U.S. presence in Honduras quickly became clear to me on a visit to Soto Cano a few years ago: within hours of stepping off the plane, I got tear-gassed. It was June 28, 2011, the second anniversary of the military coup that overthrew the government of President Manuel Zelaya. I was walking outside the base, in a broad valley about fifty miles from the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa, alongside a group of around three hundred protesters.

The protest had been under way for about forty-five minutes, and the marchers were only about halfway from the base’s southern boundary to its main entrance. Peeling off from the march, four young men walked toward the base’s gray concrete wall with spray paint in hand. Several Honduran soldiers—mostly teenagers—and black-clad riot police rushed to block them. One raised his baton over his head, while a senior officer with an M-16 pushed the graffiti artists back against the wall. Protesters rushed toward the rapidly escalating confrontation.

Suddenly a cop swung his baton at one of the young men. A police commander grabbed the man in a chokehold and started dragging him away before tripping and falling, pulling the protester down with him. People started shouting. Another cop pulled a second protester down, smacking his legs with his baton.

And then the tear gas canister exploded, a plume of white smoke engulfing us. Protesters, soldiers, and cops alike started running (only a few of the riot force had gas masks). One cop pointed a tear gas launcher at the retreating protesters. Two others pulled out semiautomatic pistols, pointing them back and forth from protester to protester. Knowing protesters had been killed during demonstrations after the coup, I thought I was about to see someone shot. I, too, began to run.

Just when I thought I had escaped the gas, I felt the burning in my eyes and lungs. I began rubbing my face, and someone shouted, “Don’t touch your eyes!” As people coughed and doused red, swollen faces with water, tensions somehow eased. Most of the protesters went back to marching, undeterred. To the tune of “Guantánamera,” they loudly sang “Los Yanquis van para fuera!”—Yankees get out.

At the base’s entrance, a line of police and soldiers was blocking the gate, some with equipment marked “U.S.A.” and shields saying POLICE in English. Inside the base’s gates, English street signs read DO NOT ENTER and YIELD. Two American soldiers looked briefly at the protest as they cruised by in a golf cart. The protesters had good reason to be at Soto Cano. During the 2009 coup against Zelaya, the Honduran military flew the president from Tegucigalpa to Soto Cano before sending him into exile in Costa Rica, fueling suspicion about a U.S. role in the overthrow. “The United States participated directly in the planning and management of the coup,” a leading human rights advocate, Bertha Oliva, told me. After coup leaders seized Zelaya, she noted, the next stop that they made was at the base. “That says everything. You don’t need documents to understand that there’s participation on behalf of the United States.” I would later meet a high-ranking Honduran Air Force officer who said he directed the pilot to stop at Soto Cano for fuel.

The U.S. government, for its part, has denied any involvement in the coup. Indeed, the U.S. military still persistently downplays its presence in Honduras, even though it has spent millions on barracks construction and “permanent facilities” at Soto Cano. In 2012 alone, the Pentagon would spend a record $67.4 million on military contracts in Honduras and authorize $1.3 billion in military electronics exports to the country, among other spending.1 Officials say the increased activity is merely aimed at countering skyrocketing drug trafficking in Central America and providing disaster relief and humanitarian assistance.

As speeches started at the protest march, a small group of U.S. human rights observers asked the comandante of the small Honduran Air Force Academy—which sits adjacent to Soto Cano—whether they could enter the base and speak with the U.S. commander. No, he said. There is “no U.S. base” here. There is only a “task force inside Honduran territory.”

“Where is the U.S. base?” a Honduran journalist asked incredulously, looking toward the expansive U.S. facilities.

The comandante closed his eyes momentarily and shook his head slightly. “Well,” he said, clearly embarrassed, “I don’t know.”2

THE ORIGINAL “BANANA REPUBLIC”

Foreigners have long exercised enormous power in Honduras and the rest of Central America. U.S. domination in the region has been virtually unchallenged for almost two hundred years, ever since President James Monroe’s 1823 doctrine proclaimed “the American continents … are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers.” At the beginning of the twentieth century, President William Taft was more direct about U.S. intentions when he said, “The day is not far distant when … the whole hemisphere will be ours in fact as, by virtue of our superiority as a race, it already is ours morally.”3

Since the 1850s, U.S. military interventions, primarily to protect U.S. economic interests, have been a recurring fact across Latin America. In Honduras, U.S. forces have intervened or occupied the country eight times—in 1903, 1907, 1911, 1912, 1919, 1920, 1924, and 1925.4 The U.S. military also intervened militarily in the nearby Dominican Republic, Cuba, Haiti, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Panama, in some cases occupying them for decades at a time. (There’s a reason many of today’s best baseball players come from Latin America.)5

One of the first invasions of the twentieth century was actually carried out not by the U.S. military but by a private one. The army’s financial backing came from “Banana Man” Sam Zemurray. When Zemurray arrived in Honduras in 1905 from Mobile, Alabama,6 the country was already weak and debt-ridden from a British railway construction fraud that had produced no railway.7 Seizing the moment, the businessman launched a coup and replaced the Honduran government with one more “sensitive to Zemurray’s every wish”—namely, land and tax concessions for his banana plantations.8 Within five years of arriving in Honduras, he controlled more than five thousand acres of plantations. A few years later, it was fifteen thousand.9 By 1913, Zemurray and his closest rivals, the Vacarro brothers from New Orleans (whose Standard Fruit Company later became Dole), accounted for two thirds of Honduran exports.

The banana companies “bought up lands, built railroads, established their own banking systems, and bribed government officials at a dizzying pace,” writes the historian Walter LaFeber. “If Honduras was dependent on the fruit companies before 1912, it was virtually indistinguishable from them after 1912. In 1914 the leading banana firms held nearly a million acres of the most fertile land. Their holdings grew during the 1920s until the Honduran peasants had no hope of access to their nation’s good soil.”10 The wealth of the country was hauled off to the United States. Honduras was left with low-wage jobs in the banana groves and with proceeds from export duties, which were often evaded and, when they did get paid, were in any case mostly pocketed by a small group of Honduran elites.11

Thus did Honduras become the prototypical “banana republic.” In popular usage (clothing company aside), the term nowadays mostly calls to mind buffoonlike Third World despots in the mold of Woody Allen’s comedy Bananas. We tend to forget its original meaning. After living in Honduras, the writer O. Henry coined the phrase to refer to weak, marginally independent countries facing overwhelming foreign economic and political domination. In other words, a banana republic is a colony in all but name.

The basic pattern established in Zemurray’s time continued after World War II. U.S. aid largely succeeded in increasing the economy’s reliance on a few export products, while Citibank, Chase Manhattan, and Bank of America took over the financial system.12 Honduras became “the closest ally to the United States,” writes LaFeber, “while remaining the poorest and most underdeveloped state in the hemisphere other than Haiti.”13

In 1954, the CIA used a banana plantation on Honduras’s particularly impoverished north coast to train a U.S.-backed rebel army that went on to overthrow the democratically elected government of Guatemala. The Guatemalan government had been guilty of threatening the near-monopoly powers of the United Fruit Company, which had bought out Sam Zemurray’s firm and made him its top official.14 The Honduran plantation where the rebels trained was also owned by United Fruit—known today to banana consumers as Chiquita.

THE “USS HONDURAS”

During Central America’s bloody civil wars of the 1980s, the U.S. presence in Honduras was so great that the country was nicknamed the “USS Honduras”: it was like a stationary, unsinkable aircraft carrier, strategically anchored at the center of the war-torn region. From the Soto Cano Air Base, the Pentagon and CIA orchestrated support for regimes in Guatemala and El Salvador, which were responsible for hundreds of thousands of deaths, and for the murderous Nicaraguan Contra insurgency, which became part of the biggest American political scandal since Watergate.

In Nicaragua, the Contras were the U.S. government’s primary weapon against the Sandinistas, who had ousted the longtime U.S.-backed Nicaraguan dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. “I speak in the name of President Ronald Reagan,” Duane Clarridge, the CIA chief for Latin America, told a group of Somoza loyalists in 1981. “We want to support this effort to change the government of Nicaragua.”15

Others in the room with Clarridge that day included Colonel Mario Davico, the vice chief of Argentine military intelligence, and Colonel Gustavo Alvarez Martínez, one of the most powerful officers in the Honduran military. The meeting produced a plan to support the Contras known as “La Tripartita.” As a Contra commander explained: “The Hondurans will provide the territory, the United States will provide the money, and Argentina will provide the front” to hide U.S. involvement.16

Honduras provided sanctuary for the Contras, and in exchange U.S. military aid to the country more than tripled between 1981 and 1982, from $8.9 million to $31.3 million. By 1984, military aid had more than doubled again, rising to $77.4 million (the equivalent of $175.9 million in today’s dollars).17 As the Honduran military received new U.S. weaponry, it transferred its old weapons to the Contras.18

There was never any real hope the Contras would overthrow the Sandinistas. Instead, in a post-Vietnam environment where direct U.S. military intervention was nearly impossible, U.S. officials saw the Contras as a second-best option. They were, in the words of former foreign service officer Todd Greentree, “a classic guerrilla counterweight who could harass and bleed the Sandinistas and whom the Sandinistas could not defeat.”19 Their “real political boss” was the CIA. President Reagan infamously described the group as the “moral equivalent of the Founding Fathers.” Greentree, like others, says that they had “the reputation of being brigands and brutes who raped women, executed prisoners, and enjoyed murdering civilians.”20

Within a year of La Tripartita’s creation, the CIA helped set up six Contra bases in Honduras and started landing cargo planes filled with weapons. CIA operatives, U.S. and Argentine military advisers, Israelis, and Chileans began training the rebels. (According to former Army Special Forces operative William Meara, he once heard a U.S. Special Forces team refer to their students as “LBGs”—little brown guys.)21 The Argentines brought the “Argentine method” of “disappearing,” torturing, and killing political opponents.22 The Contra force was soon so large it virtually took over whole Honduran provinces near the Nicaraguan border.23

In 1982, an addendum to a 1954 U.S.-Honduras military agreement gave the United States authority to base troops in Honduras, to build up airfields in country, and to build any “new facilities and installation of equipment as may be necessary for their use”—pretty much carte blanche.24 The military used the freedom to build bases for Contra, Honduran, and U.S. forces far beyond Soto Cano. These included, by my count, at least thirty-two Contra bases alone, in Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and even Florida. There were also at least sixteen bases for Honduran forces and at least nine U.S. bases in addition to Soto Cano and several secret CIA installations.25

“When Congress refused to fund the construction of new military bases in Honduras, the Pentagon built them anyway,” explains the historian William LeoGrande. Often they used military exercises as a cover.26 “When the exercises were over, the improved facilities and leftover supplies could be given to the Hondurans and the Contras.”27 Elsewhere, the military and CIA used Honduran bases to provide the Contras with supplies Congress hadn’t authorized and simply told Congress otherwise.28 By decade’s end, Honduras was “little more than a vast U.S. military base” and “a virtual U.S. protectorate.”29

In the United States, the Contras eventually became part of the biggest presidential scandal since Nixon when reporters and Congress revealed that the Reagan administration had covertly sent money and weapons to the Contras by using proceeds from secret sales of weaponry to Iran. The revelations were triply shocking: the United States had officially condemned Iran as a sponsor of international terrorism; Congress had explicitly prohibited funding the Contras; and Congress’s Iran-Contra hearings confirmed that the CIA had known since at least 1984 that the Contras were trafficking drugs into the United States.30

While the scandal eventually passed, the effects of the wars in Central America were horrific. Honduras itself, though less affected than its neighbors, suffered a decade of death squads, extrajudicial killings, and torture. Between 1980 and 1984 alone, there were 274 unsolved killings and disappearances of leftists and other dissidents.31

Most of the “disappeared” were never heard from again. Oscar and Gloria Reyes are among the few Honduran victims who lived to tell their story. As a U.S. court found in 2006, soldiers working under the Honduran director of national intelligence took the couple from their home and subjected them to beatings, mock execution, forced nudity, electric shocks on their genitals, and confinement in rooms covered in feces, blood, vomit, and urine. In court testimony, Gloria Reyes said, “I am unable to explain how I was able to withstand it.”32

Elsewhere the toll was higher: 50,000 dead in Nicaragua, 75,000 dead in El Salvador, and 240,000 dead or disappeared in Guatemala in what is widely considered a genocide. The majority of the victims were poor civilians. They died, as foreign service officer Greentree writes, in “large and indiscriminate numbers, families, clans, entire villages, the victims of torture, of bombardment, of massacre, of crossfire.”33 Hundreds of thousands of refugees flooded to neighboring countries and to the United States, whose government had provided the bullets that forced many to flee in the first place. Entire nations were left traumatized in ways that reverberate to this day.

THE ATTRACTIVENESS OF DICTATORS

The end of the Cold War effectively ended the wars in Central America. With U.S. funding for the Contras withdrawn, a GAO report declared, “The original reasons for the establishment of U.S. presence at Soto Cano no longer exist.”34 Many U.S. military and diplomatic officials agreed that the contributions made to new U.S. policy goals in the region by this “expensive, semi-permanent logistics base” were “incidental and not reason enough to maintain the presence.” Officials saw that any counternarcotics or disaster relief operations in the region could be conducted just as effectively from domestic bases.

In some ways, the GAO found, Soto Cano’s continued existence was actually counterproductive to U.S. policy.35 The GAO recommended closing the base.36 A study supported by the military’s own National Defense University agreed. It concluded that the base “does not have a significant impact on regional stability, is potentially a political problem between U.S. and Honduran governments, and unnecessarily costs the U.S. taxpayer millions of dollars.”37

Still, Soto Cano didn’t close. While overall U.S. military spending in Honduras declined significantly, “exercises were continuing through sheer bureaucratic inertia,” one former Army and Foreign Service officer explains. “Even though the original rationale for the base was disappearing, no one seemed to be considering packing up and going home.”38

In fact, the persistence of the base was due not just to bureaucratic inertia. There were also concerted efforts to create new missions and justifications for the supposedly temporary base and for the military’s entire Southern Command. After the Cold War, the combatant command responsible for Latin America found itself marginalized and with little to do. Southcom discovered its salvation in disaster and drugs.39

The first opportunity came with the damage caused in Nicaragua by 1998’s Hurricane Mitch. The Command coordinated a $30 million relief effort for America’s former enemy and used the opportunity to expand its operations in the region.40 The following year, Southcom used the closing of bases in Panama as a pretext to set up four new U.S. air bases in Ecuador, Aruba, Curaçao, and El Salvador.41 And with the “war on drugs” providing a public rationale for broadening U.S. military activities in Latin America, by the end of the 1990s Southcom saw its budget expand more than any of the other regional commands.42

After the 2009 military coup removed President Zelaya from power, the Obama administration declared an official policy of no contact with the Honduran military. Nevertheless, U.S. and Honduran military officials maintained close relations. As U.S. embassy personnel in Honduras told me, high-ranking U.S. and Honduran officers still had one another’s cell phone numbers and crossed paths in malls and other public places in Honduras. Contact continued at Soto Cano—where the Honduran military technically hosts the U.S. presence—and in other places where the two militaries interacted regularly. There was a brief dip in aid after the coup, but soon U.S. assistance to Honduran security forces began to rise again. In 2012, for example, Congress appropriated $56 million in U.S. military and police aid for Honduras.

The rising aid has come despite strong evidence that the Honduran military and police forces are connected to the skyrocketing violence in the country.43 (Honduras has the world’s highest murder rate—higher than that in Afghanistan and Iraq, more than four times that of Mexico, roughly twenty times the U.S. rate, and ninety times greater than western Europe’s.)44 Allegations have included the revival of 1980s-style death squads, and suspicions that the government’s tough-on-crime “iron fist” policing program has led to the murder of thousands of young people labeled “delinquents” or “gang members.” In a country with a population of only 6.7 million, the nongovernmental organization Casa Alianza / Covenant House has documented 9,641 people under age twenty-three murdered between 1998 and January 2014.45 The Associated Press reported in 2013 at least two hundred “formal complaints about death squad–style killings” in Honduras’s two largest cities over a three-year period, while the National Autonomous University counted 149 civilians killed by police in 2011–2013.46

Military violence, too, has escalated since the coup against President Zelaya. Human rights groups have identified more than four thousand human rights violations after Zelaya’s ouster, including arbitrary detention, torture, and political assassinations, with the de facto government implicated in scores of abuses.47 Opposition members, journalists, and activists have continued to be the victims of shootings, beatings, death threats, and political intimidation. In the lead-up to the 2013 national elections, eighteen candidates for the party led by Zelaya and his wife, Xiomara Castro, were murdered.48 While many of the facts are still unclear, there’s growing reason to fear that providing money and resources to the Honduran military and police forces contributes to rising levels of violence and insecurity throughout the country.

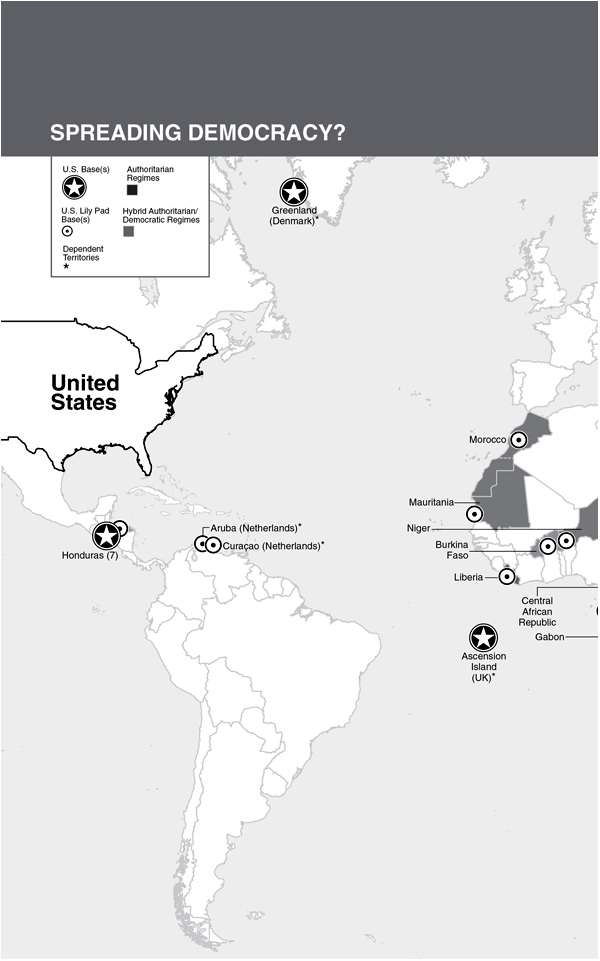

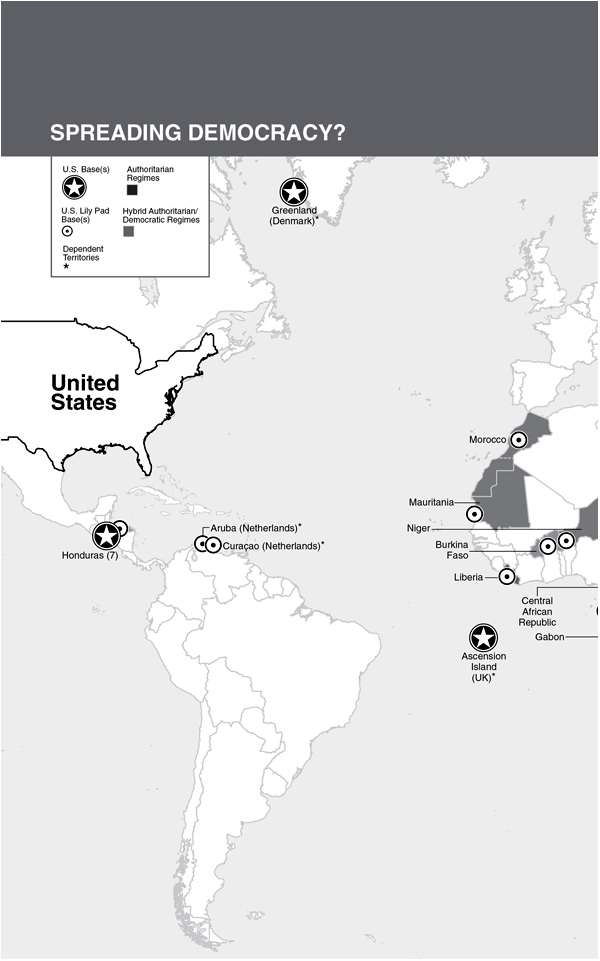

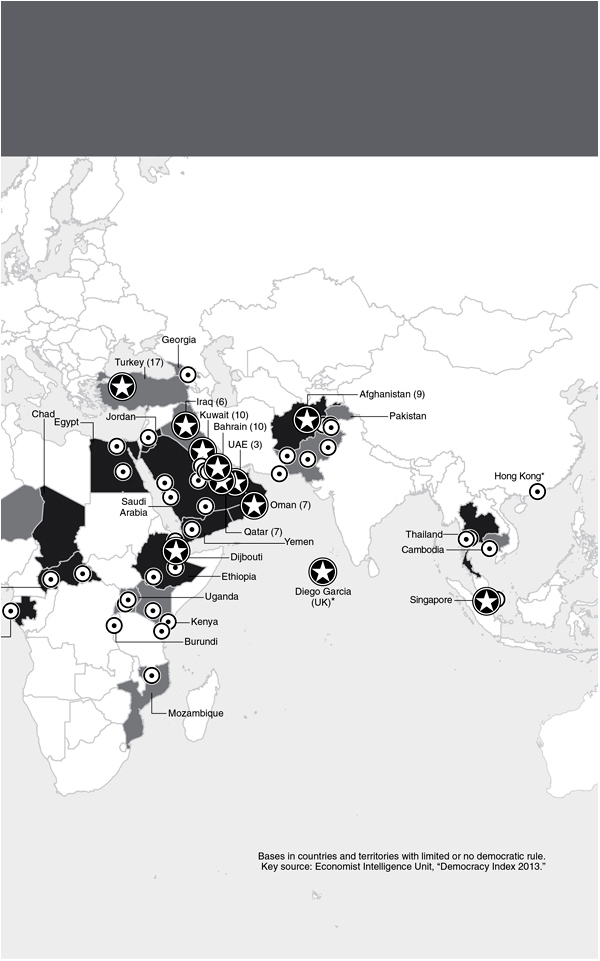

There should be little surprise about the U.S. military’s close relationship with undemocratic Honduran governments responsible for murders, torture, and widespread human rights abuses, both in the 1980s and after the 2009 coup. Despite frequently invoking rhetoric about spreading democracy and maintaining peace and security, the U.S. government has often shown few qualms about collaborating with repressive regimes to maintain access to overseas bases.

“Gaining and maintaining access to U.S. bases,” the base expert Catherine Lutz explains, “has often involved close collaboration” with corrupt, antidemocratic, and sometimes murderous governments. Since World War II, the United States has supported undemocratic and authoritarian base hosts in Afghanistan, Bahrain, Djibouti, Greece, Iraq, Kuwait, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco, Pakistan, Panama, the Philippines, Portugal, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Thailand, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, to name only a few. A large-scale study of U.S. bases created since 1898 confirms that autocratic states have been “consistently attractive” to U.S. officials as base hosts. “Due to the unpredictability of elections,” on the other hand, democratic states prove “less attractive in terms [of] sustainability and duration.”49

In some cases, U.S. officials have reacted to this unpredictability by intervening in ostensibly democratic processes to produce outcomes to their liking and ensure ongoing base access. In the lead-up to Italy’s crucial 1948 national elections, for instance, the CIA, the State Department, and other agencies of the U.S. government used propaganda, smear campaigns, threats to withdraw aid, and the appearance of warships off Italy’s coasts, among other tactics, to help the Christian Democracy party defeat Italy’s favored communist and socialist parties. The Christian Democrats, who maintained a client relationship with the U.S. government and provided widespread base access, then dominated Italian politics for the next five decades. (Their rule ended only when a massive 1994 corruption scandal reshuffled all of Italian politics.)

The U.S. government also provided similar covert and overt support in the aftermath of World War II for the right-wing Liberal Democratic Party in Japan and for dictatorial governments in South Korea. This support ensured that of the four countries worldwide hosting the largest number of U.S. bases, three saw virtually unbroken one-party rule for half a century or more. The other, Germany, had twenty years of one-party rule after the war.50

More recently, the U.S. government offered only tepid criticism of the government of Bahrain during its violent crackdown on pro-democracy protesters. According to Human Rights Watch and others (including an independent commission of inquiry appointed by King Hamad bin Isa al-Khalifa), the government has been responsible for abuses including the arbitrary arrest of protesters, torture and ill treatment during detention, torture-related deaths, the prosecution of political opponents, and growing restrictions on freedoms of speech, association, and assembly.51

After the 2013 military coup in Egypt, which has a relatively small U.S. base presence plus broader military and political ties related to the Arab-Israeli conflict, U.S. officials took months to withhold some forms of military and economic aid despite more than 1,300 killings by security forces and the arrest of more than 3,500 members of the Muslim Brotherhood. Despite these steps, according to Human Rights Watch, “little was said about ongoing abuses.”52 Likewise in Thailand, the U.S. has retained deep connections with the Thai military, even though it has carried out twelve coups since 1932.53

Research by the Johns Hopkins political scientist Kent Calder confirms the “dictatorship hypothesis”: consistently, “the United States tends to support dictators [and other undemocratic regimes] in nations where it enjoys basing facilities.”54 Honduras and Bahrain, Egypt and Thailand, are far from an aberration. At the same time, research shows that authoritarian rulers have often used a U.S. base presence to ensure and extend their own domestic political survival. Some rulers, like the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos, the South Korean dictator Syngman Rhee, and Kyrgyzstan’s Askar Akayev, have used the bases to extract economic assistance from U.S. officials, which they have then shared with political allies to shore up domestic support. Others have relied on U.S. bases to bolster their international prestige and legitimacy or to justify violence against domestic political opponents. After the 1980 Kwangju massacre, in which the South Korean government killed around 240 pro-democracy demonstrators, strongman General Chun Doo-hwan explicitly cited the presence of U.S. bases and troops to suggest that his actions enjoyed U.S. support.55

Whether or not the United States really supported Chun’s actions is a matter of continuing debate. But it is clear that in countries with U.S. bases, American officials have repeatedly muted their criticism of repressive regimes and downplayed the promotion of democratization, decolonization, and human rights. In the case of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, for example, a 1969–70 U.S. Senate investigation discovered that annual U.S.-Spanish military exercises were designed to prepare a military response to an anti-Franco uprising and keep his regime in power despite its domestic repression and continuation of Spanish colonial rule. As the base expert Alexander Cooley puts it, “The U.S. basing presence may have diminished these host countries’ overall national sovereignty, but it also afforded their rulers significant private political benefits.”56

The result has been a pattern of U.S. support for violence and repression. Not surprisingly, this can also be a self-reinforcing cycle. As the protests at Soto Cano suggest, supporting repressive regimes builds resentment and opposition to the United States—which makes the eviction of U.S. bases all the more likely when countries do transition to democratic rule.57 Knowing this, the U.S. military has even more incentive to prevent that transition from taking place.

BLOWBACK

While some defend the presence of U.S. bases in repressive, undemocratic countries as necessary for supporting “U.S. interests” (that is, generally, corporate economic interests), backing dictators and autocrats frequently harms not only host nation citizens but also the United States and U.S. citizens as well. Honduras provides a telling example of what the CIA would call “blowback” from U.S. support for repressive regimes during Central America’s civil wars.58 Popularized by the onetime CIA analyst Chalmers Johnson, the term “blowback” refers to the unintended consequences of covert operations whose causes the public cannot understand precisely because the precipitating operations were covert. Put simply, the United States reaps what it secretly sows.59

In the 1980s, the U.S. government helped fuel Central America’s dirty wars through its covert and overt support for brutal, drug-dealing Contras and repressive regimes in Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador. These wars killed and injured hundreds of thousands, frayed and destroyed social relations, and increased poverty, insecurity, and drug trafficking in the region. The wars also led to widespread forced migration, including widespread flight to the United States.

These refugees typically ended up in the poor neighborhoods of cities like Los Angeles. Once there, many impoverished boys and young men (and, to a lesser extent, girls and young women) found themselves joining U.S.-born-and-bred gangs. In addition to terrorizing U.S. neighborhoods, these refugee gang members were often arrested and deported back to their home countries, where they soon established new branches of their U.S.-based gangs.60 In turn, these gangs became centrally involved in the growth in drug trafficking in Central America—which the Contras helped kick-start—as drug traffickers took advantage of the region’s poverty and instability to create a new transshipment hub between South American producers and North American points of sale.61 The main result of the U.S. drug war has been merely to shift transportation routes while increasing violence and doing little to affect consumption. Squeezing trafficking in one place has created a “balloon effect,” pushing the trade from the Caribbean to Honduras and other parts of Central America. Today, an estimated 90 percent of the cocaine shipped from Colombia and Venezuela to the United States goes through Central America, with more than one third of that total going through Honduras.62

The drug trade’s violence and the proliferation of gangs have been mutually reinforcing. Combined with the violence of living in the second-poorest country in the hemisphere, there should be little surprise that Honduras has the world’s highest murder rate (followed by El Salvador, Belize, and Guatemala in the top five).63 Amid such deteriorating and desperate conditions, there should be equally little surprise that the United States has seen so many Central American migrants arriving at our borders. Like the migrants who arrived at U.S. borders in the 1980s, these new refugees are in part a kind of second and third wave of blowback from decades of supporting repressive governments with bases and military aid.

The United States is not responsible for all the problems in Honduras and Central America. But the country’s violence and insecurity today are directly linked to the violence and insecurity produced by almost two centuries of continuous U.S. domination, including the “USS Honduras” period of the 1980s.

There was a missed opportunity for the United States in Latin America at the end of the Cold War. After supporting a violent, repressive regime in Honduras and using the country to support even more murderous regimes in El Salvador and Guatemala, the United States should have completely withdrawn its bases and forces from Honduras and the rest of Latin America once peace came. There was no need for them in a region facing almost no external security threats or cross-national conflicts. Any humanitarian, training, and counternarcotics operations in Honduras could have been carried out from bases in the United States, just as the military does in many other countries.

The same remains true today. There is simply no reason for Soto Cano to exist. As long as it continues to exist and as U.S. forces become ever more entrenched at Soto Cano and elsewhere in Honduras, the United States becomes increasingly complicit with the military that carried out the 2009 coup and with military and police forces implicated in murders and other serious human rights violations. The only question now is what bloodshed and blowback will occur in the future thanks to the U.S. military’s growing involvement in Honduras today.

Charles “Lucky” Luciano, notorious leader of New York and Naples mafias, in a 1931 mug shot.