Thirty-One

“Hold on,” Matthew said. He could smell his own sweat and burned hair. He felt a hundred years old, but now was not the time to give in nor give up. He had said this because he felt, also, the hand of Pretty Girl Who Sits Alone trying to open the fingers that had seized her arm.

“Matthew,” she said quietly, tasting the name for the first time.

He tightened his grip both on her and the cutlass. Above them the ceiling of clouds and cherubs had begun to resemble a ravaged Hell rather than the repose of Heaven. Around them the burning books flamed and at any other moment Matthew might have wept for them.

“I can’t go home,” she said, quieter still.

“We can get up there.” Matthew saw places in the splintered planks that might serve as hand and foot-holds to climb up to the door. The ceiling was beginning to fall in. The clouds were heavier than they looked. Time was quickly running out, for tremors still disturbed the cracked walls and tilted floor. “Come on,” he said. “We have to go.”

“No,” she said. “That way is for you, not for me.”

He peered into her face. The blood crawled along her cheek, but she seemed neither to notice nor care; her soul had already turned away from the flesh that contained it.

“We’re both going up,” he vowed, aware that it was only a matter of seconds before either the ceiling collapsed upon them or the cutlass’s blade pulled loose.

“I came to your room,” said the girl, “to give you the only gift I could. Now I need you to give me a gift. Let me go, Matthew.”

“I won’t. No.”

“You must. I want to go dreaming now. I want to wash myself clean. Don’t you understand?”

“You’re alive!” he said.

But she shook her head, sadly still.

“No,” she answered, “I am not.”

And he did understand. He hated the understanding of it, but he did. She was part of nature, had been defiled and debased, and she wished to return to what she had been. Perhaps her feeling about death was completely contrary to his … or perhaps she just believed in a better afterlife than he. Whatever, he knew she wanted this gift … and yet … how could he open his fingers and give it to her?

“There’s a ship waiting.” He prayed to God it was still waiting, for the gray light was strengthening and the first ruddy glow had appeared to paint the waves. The sweat was on his face, his shoulders and back were cramping, and he couldn’t hold this position much longer. To emphasize the danger and lack of time, a piece of the ceiling as big as a kettle crashed down upon the tilted floor a few feet beyond the girl.

“It waits for you,” she answered, her face calm, her eyes soft and yearning for peace.

“No,” he said. “No, we’re both going.”

“Matthew … whoever you are, and whatever you are … you must know that being free means … I make my own choice.”

“The wrong choice.”

“Mine,” she said.

Her fingers began to work again, at his. Hers were strong. She stared into his face as she worked, and he resisted. Yet as his fingers were pushed away, he began not to try so very hard.

“I will find him,” she said. “I will tell him about you. He will be very glad to hear.”

“Who?” Matthew asked.

“You know,” she told him, and then Pretty Girl Who Sits Alone smiled.

And slid away.

As she went toward the edge she turned her body, and Matthew saw her go into the air as if diving into a new life, one he could not possibly understand. She went silently and beautifully, even as he cried out as if struck to the heart. Which he was.

She disappeared in a billow of dark green, like an arrow returning to a forest unknown. And perhaps her forest did lie beyond the blue silence of the deep, and in that awesome place beyond the comprehension of Matthew Corbett she would return to who she had been, proud and innocent and clean.

He did weep. Not for the burning books and the ideas of men that flew away on their wings of ash, but for the Indian girl who had just taken flight from this world to the next.

“Climb up! Hurry!”

Matthew looked up toward the door. Minx Cutter stood there, with a bloodied piece of bedsheet pressed to her forehead. Another cut on her left cheek leaked red. She wavered on her feet, her strength nearly gone. Matthew reasoned that Aria Chillany had gone to a reunion with Jonathan Gentry, which would be her small and nasty room in the diseased mansion of Hell. It appeared to him that Minx was holding herself up with willpower alone, and on that account she was a formidable figure.

“Climb up!” she repeated, urgency in her voice, as various sounds of cracking stone came from the walls and ceiling. Another large chunk fell, to Matthew’s right. White dust powdered the air. It was time to get out of here, and quickly.

The first reach was the most dangerous. He had to let go of the cutlass and grip the edge of a splintered plank. Then he started up using similar hand-and-foot holds that were precarious at best. When he got near enough to Minx she leaned down and grasped his outstretched hand, and pulled him up into the warped corridor.

“The bag of gold,” Matthew told her. She already had gone to her room to get the forged orders for the release of the Nightflyer, complete with the professor’s octopus stamp, but it was doubtful such a paper would be needed today. The staircase was still intact, though the ceiling was falling to pieces, and on the second floor Matthew took a moment to enter his room—its floor crooked and the left wall partially collapsed—and retrieve the moneybag, which he shoved into his shirt. He realized then that the room to the left of his, though it had a balcony the same as his own, was not really a room and had been empty, according to the map he’d been given. The collapsed wall revealed another staircase curving down. It had to be, he realized, the stairway to Professor Fell’s domain. Not by happenstance had Matthew been given the quarters next to it.

He entered the corridor again, where Minx waited. Without hesitation he kicked the next door in. It swung open easily, for the quake had already sprung its lock.

“What is this?” she asked.

“You should go out to the wagon,” he told her. “Keep anyone else from taking it. I’m going down this way.”

“Why? What’s down there?”

“Him,” he said, and she understood.

“I’ll wait only for a short while. Falco might have taken the ship out already.”

“If he has, he has. We’ll find another way off.”

She nodded and peered into the dark staircase. “Good fortune,” she said, and then she turned and went her own path.

Matthew couldn’t blame her. He didn’t want to go down those steps either, into that darkness, but it had to be done.

He descended. A few torches had been set into the walls, but they were all extinguished. The staircase shook beneath his feet and stone dust rained from above. The castle was dying, perhaps to join the rest of Somers Town in its underwater sleep. Fate, it seemed, had caught up with Fell’s uneasy paradise. Still Matthew descended, past the first floor and into the castle’s guts. Or bowels, as might be more proper. The staircase curved to the left, the risers cut from rough stone. He came upon two torches still burning, and he paused to take one of them from its socket. Then, his confidence made more solid by the light, he continued on his downward trek.

A gate of black iron was set at the bottom of the stairs, but it was unlocked. Matthew pushed through and winced as the hinges squealed. Another torch burned from a wall in the narrow corridor ahead, and Matthew followed its illumination. Above his head there were nearly human groans as stone shifted against stone; even here, at this depth, the castle had been mortally wounded. Deep cracks grooved the walls and floor. Matthew walked on, pace after careful pace. He came to a branch in the corridor and decided to follow the straighter route. It led him to the wooden slab of a door that hung crooked on its hinges. He pulled it open and found a spacious white-walled sitting room and a candelabra with three tapers still burning atop a writing desk. The ceiling, riddled with cracks, was painted pale blue in emulation of the island’s sky. The furniture was tasteful, expensive, and also painted white with gold trim. Matthew went through another doorway and found a bedroom with a large, canopied white bed. His attention was drawn to what hung on a number of pegs on the wall next to that bed: the tricorn hats Professor Fell had worn on his visits to Matthew’s room, a white wig the same as worn by the castle’s servants, and a battered straw hat that might have been the topper for any of the island’s farmers.

He felt time was short, but he had to open and search a chest of drawers in the bedroom. He discovered in the drawers not only the elegant suits Fell had worn as well as the opaque cowl and the flesh-colored cloth gloves, but the sea-blue uniform of a servant. Also there were regular breeches with patched knees and white shirts that appeared worn and in need of stitching. All would have fit a slender man a few inches taller than Matthew. In addition, there were the shoes: two pair polished and gentlemanly, one pair scuffed and dirt-crusted.

He began to believe that Professor Fell at times dressed as a servant to move about the house and as a regular native to move about the island. Which begged the question … was Fell a native himself? A man of color? And perhaps Templeton … his son … had been harrassed and beaten to death on a London street partly because his skin was cream-colored, and darker than that of the average English boy? There was a reason, Matthew realized, why Temple’s portrait had been done in colored glass.

But the real question was … where was Professor Fell now?

The deep noise of grinding stones told Matthew he had to find a way out of here, or retrace his path to the staircase. He went through the doorway out into the corridor again, his torch held before him, and started back the way he’d come. He was not very far along when he caught sight of another torch coming toward him, and a giant figure in white robes and a white turban illuminated in the yellow light.

Sirki stopped. They faced each other at a distance of about thirty feet.

“Hello, young sir,” said the East Indian giant, and the light he held made the diamonds in his front teeth sparkle.

“Hello,” Matthew said, his voice echoing back and forth between the walls.

“We have suffered quite a mishap here. Quite an explosion, up at the far point of the island. Do you know anything about that?”

“I felt it, of course.”

“Of course. I see your stockings are very dirty. Muddy, perhaps? Did you get through that swamp all by yourself, Matthew?” Sirki waved a hand in his direction. “No, I don’t believe you did. Who helped you? It’s not only me asking. The professor would like to know. When that blast happened, his first thought was of you. And of course you were not in your room. Neither was Miss Cutter in hers. Now … why would she have helped you?”

“She likes me,” Matthew said.

“Oh. Yes. Well, then.” Sirki withdrew the sawtoothed blade from its sheath in his robes and walked forward a few steps. Matthew retreated the same number. “The professor,” said Sirki, “has left this place. He instructed me to find you, and when I went to your room I found that the stairway was revealed. You had to come down here, didn’t you? I am also instructed to tell you … that your services are no longer needed, and unfortunately Professor Fell will be unable to pay you your three thousand pounds.”

“I thought he might wind up withdrawing that offer.”

“Hm. He asked me to tell you that he will not be very much damaged by this little incident. Certainly he would not have wished this, but he has many irons in the fire.” Sirki inspected the brutal edge of his blade. “He is sorrowful for you, though. That you chose to hurt him out of your … how did he put it? … your blind stupidity. Ah, Matthew!” He advanced a few steps nearer, and again Matthew retreated. The hideous weapon gleamed with reflected torchlight. “To have come so far and be on the verge of such greatness … and then to fall back again, as dirty as the swamp.”

“The swamp,” Matthew said, “is cleaner than the professor’s soul.”

“He wishes me to cut off some part of you and bring it to him to demonstrate that you are dead,” said the giant. “What would you suggest, young sir?” To the silence that followed, Sirki smiled and said, “Let me decide.”

He strode forward, demonic in the torchlight. The sawtoothed blade was upraised, capable of horrendous injury with one swing. Matthew backed away, his heart hammering. He thrust the torch forward to keep the beast at bay.

“No use in that,” Sirki said almost gently. “I shall put that down your throat if I please.”

And Matthew knew he could. Therefore Matthew chose the better part of valor. He turned and ran for his life.

Sirki came after him, taking tremendous strides. The branch in the corridor was ahead. Matthew took the untrodden way, running as fast as he could. Sirki was right behind him, the white robes billowing like the wings of a deadly angel.

The corridor suddenly widened into a space where there sat two simple chairs with dark stains of what might have been blood upon and beneath them. Gory chains still lay about the chairs, but there were no bodies. Smythe and Wilson had already gone to the tearing beak and eight arms of Agonistes. Matthew’s light displayed three cells. He was in the dungeon under the dining hall, probably used to confine pirates and other criminals of note. In the center cell stood Zed, bald and bearded and wearing his ragged clothing. Zed had his hands gripped around the bars, and when he saw Matthew the mouth in the tribal-tattooed face gave a mangled roar of recognition.

Matthew heard Sirki coming. He saw a ring bearing three keys hanging on the wall. Sirki was almost into the chamber. Matthew dropped the torch to the floor and picked up one of the chairs. He threw it at Sirki’s legs as the giant came through the corridor, and Sirki crashed down upon the stones.

Matthew plucked the keys off the wall and ran to Zed’s cell. The first key did not fit. He looked back and saw Sirki up on his feet, lumbering toward him. The wicked blade flashed at Matthew’s head, but he had already ducked. Sparks flew up from the meeting of sawteeth and iron bars. Matthew threw the ring of keys between the bars into Zed’s cage, and then he got hold of the fallen torch and backed warily away as Sirki advanced upon him.

“This can go more easily for you,” Sirki promised. “I’ve grown to respect you. I can make your death very quick.”

“I’d rather stretch my life out a bit longer.”

“I’m sorry, but that will be im—”

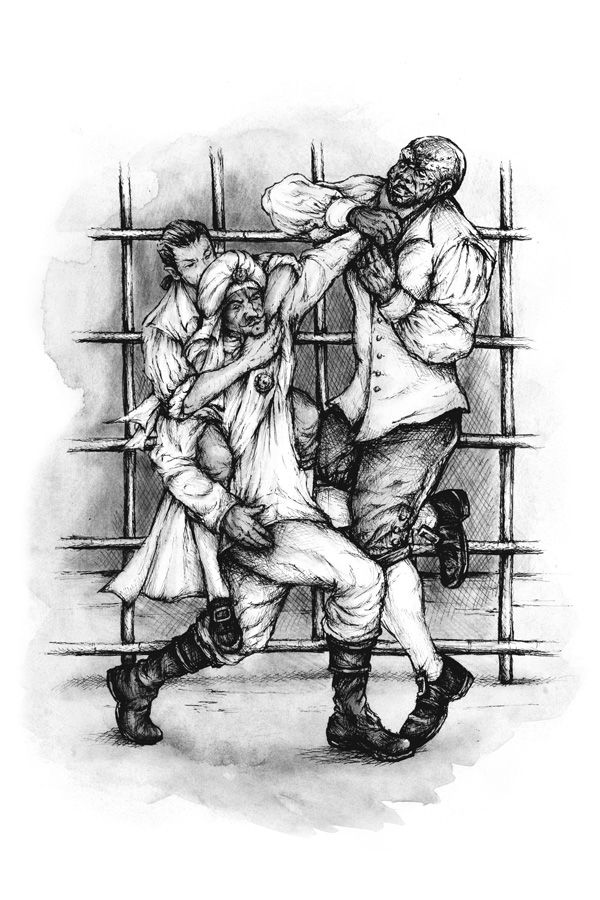

Sirki was interrupted by the noise of the cell door banging open. When the giant looked in that direction to see Zed emerging from the cage Matthew stepped in and struck the torch at the side of his head, but Sirki had already recovered and deflected the torch with his own. Then he whirled to meet Zed with his blade … an instant too late, for Zed’s fist met Sirki’s mouth in a jarring smack of flesh and bone and though the knife swung viciously at Zed’s chest the Ga had darted away with admirable agility.

Sirki was caught between Matthew with his torch and Zed with his fists. He slashed first at one and then the other, and both kept their distance. Then Zed plucked up one of the lengths of chain from a chair. Sirki grinned in the flaring light. Blood was on his mouth, and he was minus a diamond as well as a front tooth.

“Ah!” he said. “I do get to kill you, after all.”

Matthew lunged at him with the torch from the right side, aiming at the knife hand. Zed swung the chain and struck Sirki a blow across the left shoulder. Sirki spun toward Matthew and rushed him in an attempt to cancel the weaker threat, but Matthew swept the torch past Sirki’s face to keep him away. Then the chain whipped out again across Sirki’s back, and now the giant in an instant of what might have been panic threw his torch at Zed and followed it with his own huge body and the deadly blade upraised.

Matthew had already seen, in the Cock’a’tail tavern in New York the October before, what Zed could do with a chain. Now Zed stood his ground and lashed the chain out; it curled around the forearm of Sirki’s knife hand, and just that fast Zed used the momentum to swing the giant crashing against the bars of the nearest cage. Sirki did not give up the knife, and grasping the chain with his free hand he hauled Zed toward himself like reeling in a hooked fish.

Zed’s feet slid along the stones. He tried to right himself but the giant’s pull was too strong. The knife waited with what seemed to be eager anticipation.

Then Matthew struck Sirki across the left side of the head with a second chain he’d picked up. The killer’s turban unravelled from the blow. Sirki’s eyes glazed for perhaps two seconds, his knife wavered and in this space of time Zed was upon him.

They grappled for the blade. It was the battle of the giants, brute against brute. Zed smashed Sirki in the face again with a heavy fist. Sirki grasped hold of Zed’s throat with his free hand, an enormous implement of murder, and squeezed hard enough to make the cords stand out. They whirled toward Matthew in their fight and hit him with their shoulders, picking him up off his feet, throwing him to the floor and leaving him breathless in the winds of violence. He was amazed to see Sirki actually lift Zed off the floor with the hand at his throat. Zed hammered at Sirki’s face and head while grasping the knife hand to keep those sawteeth from flesh. They slammed against the opposite wall so hard Matthew thought it would complete the destruction of the castle that the earthquake had begun. From above pieces of stone fell, and drifts of dust. Still the two fought on, Sirki’s fingers digging into Zed’s throat and Zed reshaping the giant’s features with the mallet of his fist.

Zed began to make a gasping, gagging sound, and Matthew saw his blows weakening. Sirki was about to defeat the Ga, an unthinkable proposition. Matthew’s torch had spun away in the collision and lay beyond the fighters. He had to decide what to do, and quickly. Though he was afraid out of his wits he took a running start and leaped upon the giant’s back, at the same time looping the chain around Sirki’s neck and squeezing as if his life depended upon it.

Sirki thrashed wildly but Matthew hung on. He was a rider of a different nature this time, and damned if he’d be thrown. The giant’s hand left Zed’s throat to reach back for Matthew’s hair, but suddenly there was a crunching noise and Zed had attacked the knife hand with ten fingers. He succeeded here where he had failed in their battle on Oyster Island, for Sirki’s knuckles sounded like walnuts being stomped under rough boots. The knife clattered to the stones, but just as quickly Sirki kicked it out of Zed’s reach. Matthew still hung on, as the wounded giant pitched and bucked. Zed hit Sirki so hard in the jaw that the man careened back and nearly broke Matthew’s spine against the wall. Then Matthew slithered off, his breath and strength gone, and through a red haze he saw Zed take his place by leaping upon Sirki’s back. The Ga grasped the chain and began to strangle the giant, the muscles in his forearms strained and quivering. Sirki fought back by slamming Zed continually against the wall with blows that Matthew thought must be near breaking bones, yet Zed would not be thrown off nor denied his moment of revenge.

The chain sunk into the flesh of Sirki’s throat. The giant’s eyes bulged and blood streamed from his nostrils. His mouth opened in a hideous gasp, and Matthew saw that the second diamond-studded tooth had been knocked out.

Still Sirki fought. Still Zed clung to his back and choked him with the chain, which had now nearly disappeared. Matthew thought with horror that in another moment Sirki’s head was going to be cleaved off by the chain. Sweat stood out in beads on the faces of both men, and then Sirki’s eyes began to bleed.

Still Sirki crashed Zed against the wall, though the fury was weaker. Still the muscles of the Ga’s arms worked. Sirki began to emit a high keening sound, an eerie gasping for departing life itself. His eyes were wide and wild and as red as the sun going down.

Then Sirki’s legs buckled and he fell to his knees. Suddenly he was not so gigantic. Zed stayed astride him. The Ga’s teeth were gritted, his huge shoulders thrust forward, his body trembling with the effort of delivering death to one who would not accept it. Sirki made an effort to stand. He got one foot planted and, incredibly, began to lift himself and Zed off the floor. But the pressure from Zed’s hands and the chain never faltered, and suddenly Sirki’s face took on a waxen appearance, the eyes pools of blood, and from his gasping mouth a dark and swollen tongue emerged. It quivered rapidly, like the tail of a rattlesnake.

Something crunched inside Sirki’s neck. The head hung at an angle, as Gentry’s had upon being sawed off at the dinner table. The giant’s body shivered, as if feeling the chill of the grave. Matthew saw that the hideous eyes were sightless. At last Sirki’s spirit seemed to flee the body, for the keening gasp ceased on a broken note to go along with the broken neck.

Zed let go of the chain, which was buried somewhere in there. He climbed off Sirki’s back. For a moment the giant remained on his knees, obstinant far beyond the end. Then the corpse pitched forward and the stone floor added a cruel smashing to the twisted face.

Zed crumpled to his own knees and released a shuddered moan. He was all used up.

But the stone dust was falling now in greater volume. Matthew heard a dozen cracking noises from above. Suddenly a piece of stone the size of Sirki’s dead body crashed down on the other side of the dungeon, followed by smaller bits of rubble.

“We have to get out!” Matthew shouted, and standing up he grasped hold of one of the Ga’s arms to pull him to his feet, a task he could accomplish only in his most boastful dreams.

Language barrier or not, Zed fully understood. He nodded. Something on the floor nearby caught his attention and he scooped it up before Matthew could see what it was. Then, getting up on his own power, he took Matthew by the back of his collar and pulled him into another corridor at the far right of the room. It was dark in here and Matthew could see nothing. In a few seconds Zed stopped. There was the noise of a bolt slamming back. Zed pushed forward. A heavy door opened into gray morning light. The garden lay before them, and a pathway toward the front of the castle. Now Matthew took the lead, urging Zed to follow.

Matthew fully expected Minx to be gone, but she was still waiting at the wagon and tending her wounds with the bloody cloth. “Did you enjoy your wanderings?” she snapped at him, though there was some relief in her voice. “You damned fool!” she added, and then she took stock of the Ga. “Who is this?”

“My new bodyguard,” said Matthew.

Minx used the whip to spur the team into motion. As they took off at a gallop along the road to the harbor, there came a noise like the discordant shrieking of a chorus of demons. Matthew and Zed looked back to see a shimmer of dust rising up around Castle Fell. Suddenly part of the cliff itself broke away, and the entire castle tilted toward the sea. The cobra head of one turret toppled, then a second and a third. Pieces of red slate flew like gulls. Every arched window that had not already broken shattered in an instant. With a tremendous, ungodly grinding of catastrophic forces fully half the castle tore away from its own tortured stones and pitched downward into the waves, leaving furniture hanging from rooms and splintered stairways leading to no destination but the somber sky.

“My God,” Matthew whispered.

Zed gave a rough grunt that might have been accord.

Minx Cutter had never looked back. “To Hell with all of ’em,” she said, and she lashed the team for greater speed.