#19 Private Arthur Leonard Smith

1ST AUSTRALIAN FIELD AMBULANCE, AAMC

TO THE NORTH-WEST, THE AUSTRALIAN contingent had their sights firmly set on Mouquet Farm. Tending to the health of his countrymen as they advanced towards this perilous objective was 25-year-old Arthur Smith. His enthusiasm to fight in the war had been evident when he enlisted before the conflict was two weeks old in August 1914. A railway signalman from Haberfield, Sydney, Arthur, the son of a greengrocer, was immediately routed into the Australian Army Medical Corps and one of the field ambulances belonging to the 1st Australian Division. He joined his unit in time to witness the Gallipoli landings, where scores of wounded lay on the landing beach crying for attention from overworked medical men. By the end of the year he had become yet another victim of inherent sickness and disease in the unhealthy climate of the Dardanelles and was evacuated before his comrades, rejoining them at Alexandria having made a full recovery in March 1916. By the end of the month Arthur had disembarked in France. While the Australians grew accustomed to the Western Front, his family had already suffered tragedy when his younger brother, Stanley, had died of septicaemia at a casualty clearing station further north after a brief illness on 29th June 1916.

Bombardments in the direction of Mouquet Farm had been going on since 6th August. Two days later movement towards it began, ready for a full-blown assault on this enemy strong point. The previous occupants had got the line within striking distance, but in doing so, in just over a week they had lost nearly 5,000 men. The returning 1st Division was not at full strength, despite reinforcements coming in during its respite. The men were expecting to fight again, but it was still with dread that they returned, ‘in much the same spirit in which a boy accepts that of an inevitable disciplinary thrashing’.

The ground was terrible: ‘the flayed land, shell-hole bordering shell-hole, corpses of young men lying against the trench walls or in the shell holes.’ It was an eerie sight:

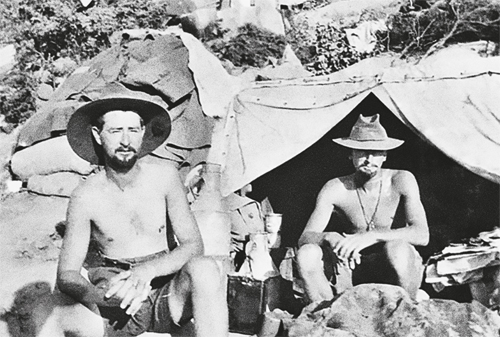

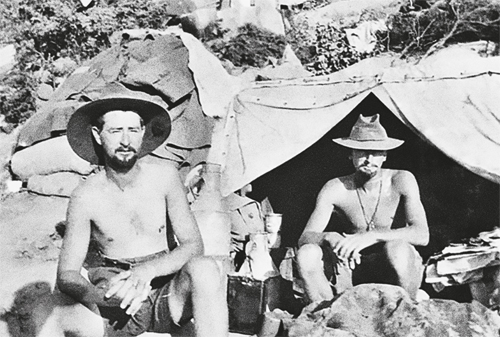

Private Arthur Smith (right) at Gallipoli. (Australian National War Memorial)

Some – except for the dust settling on them – appeared to be asleep; others torn in half; others rotting, swollen, and discoloured … the air fetid with their stench or at times pungent with the chemical reek of high explosive.

The landscape had become featureless. ‘The whole area resembled one big, ploughed field.’ It was nearly impossible for battalions to ascertain where they were going. ‘An immediate result was that the perplexed troops and their commanders frequently found it impossible to determine their position, even in the daytime.’ At night, especially during a barrage, reliefs and parties of carriers or workers sometimes became completely lost.

Plans were already under way to swap out the Australians, who had seen quite enough of Pozières and the surrounding area, and bring in the Canadian Corps; but that would not be until the end of August. In the meantime, the Australians’ work was far from done. Objectives had still been allotted for them to secure before their departure. The terrain was difficult: a narrow front on the summit and western slope of a ridge, so cramped that one or two battalions were enough to cover it going forward. Here the Australians were to make a significant attack in the third week of August.

On 14th August Arthur Smith’s field ambulance unit moved en masse down to the Brickfields at Albert ready to set up to operate fully from Bécourt, 5 miles to the south-west of Pozières, the following day. Arthur’s unit was then carefully spread out behind the battlefield. The field ambulance was frequently taking in men from other units where necessary to boost its numbers, and the nature of the work meant that the twenty-two officers and nearly 600 men on its strength as August progressed divided up their thirty-five motor ambulances and nine horse-drawn wagons and worked broken down into various teams at five different locations leading up to Pozières and as far forward as one of the OG Lines.

With no major attack taking place, the sheer ferocity of the German barrage and the havoc it wreaked on the ranks of the Australian units in the line was illustrated when Arthur’s field ambulance took in nearly 350 men in its first two days of operation at Bécourt. Australian preparations for the upcoming offensive were also being hampered by counter-attacks coming from Fabeck Graben, a significant German line that ran eastward away from Mouquet Farm, and medical men such as Arthur worked around the clock to treat and evacuate the wounded. He had been sent out with a team to set up a link in the chain of evacuation on a sunken road to the north of Contalmaison, which ran north-east towards Martinpuich, a position that was acting as both a regimental aid post and an advanced dressing station for the wounded, who had mainly been maimed by the shellfire at the front. Little stretcher parties of four or five worked constantly to collect the wounded from the open ground and in range of the enemy barrage, ‘often, for want of a Red Cross flag, under a white handkerchief or other rag’. On 17th August, as Arthur’s field ambulance processed another 257 cases, he was killed at his post.

In just six weeks around Pozières, the Australians had suffered nearly as many casualties as they had in the entire Gallipoli campaign. Originally buried at the site of the dressing station, Arthur Smith was eventually exhumed for a proper burial in 1925 as the battlefield was cleared and laid to rest at Pozières British Cemetery, plot IV.L.50.