01 THE FREEDOM TRAIL

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

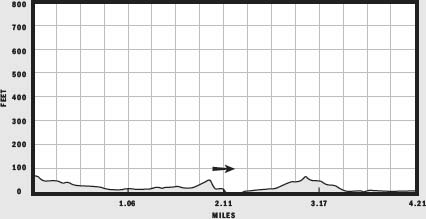

LENGTH: 4.21 miles

CONFIGURATION: Point to point

DIFFICULTY: Easy

SCENERY: Boston’s most historic streets; Boston Common, America’s oldest public park; the Charles River; and views of Boston Harbor

EXPOSURE: Mix of sun and shade

TRAFFIC: Heavy

TRAIL SURFACE: Pavement

HIKING TIME: Allow at least 2 hours

SEASON: Most of the major sites on the Freedom Trail are open 7 days a week 9:30 a.m.–5 p.m. in the summer and 10 a.m.–4 p.m. in the off-season; however, times vary by site. The last tour of the USS Constitution is at 3:30 p.m. year-round. All sites are closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Years’ Day.

ACCESS: Free

MAPS: See longer note at end of description.

FACILITIES: Restrooms can be found at the visitor centers on Boston Common and State Street and at Faneuil Hall, Quincy Market, the Charlestown Navy Yard, and Bunker Hill. In warm months, restrooms are available at the North End Visitor Center, located near the Old North Church.

WHEELCHAIR TRAVERSABLE: Yes

The Freedom Trail

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 330052

Northing: 4691567

Latitude: N 42° 21' 28"

Longitude: W 71° 03' 49"

Directions

The best way to get to the start of the Freedom Trail is by public transit. If you’re coming from outside the city, it’s best to park near an outlying subway station and take the MBTA to Park Street. Both the Red and Green lines run directly to the Park Street Station, located on the Boston Common close to where the trail begins.

IN BRIEF

This hike, which is clearly marked with a painted red line or inlaid bricks—tours Boston in the footsteps of those who drove the American Revolution. Starting at the State House, the trail travels north, reaches Paul Revere’s House, then crosses the Charles River to Charlestown, where it climbs to the Bunker Hill Monument and concludes at the USS Constitution—taking in a great many more historical sites along the way.

DESCRIPTION

Begin the hike on the steps of the “new” State House, located on Beacon Street just north of Boston Common. The Freedom Trail, marked with red paint or, in some places, brick, is easy to follow.

Before setting out, pause to look across the common. Before the ships of John Winthrop and company landed, these 44 acres belonged to William Blackstone (or Blaxton), the first white man to settle Shawmut. Eventually overwhelmed by shiploads of new arrivals, Blackstone retreated to Rhode Island, seeking peace and, ironically, freedom, from the Puritan’s rigid code of law.

Long after being liberated from Blackstone’s ownership, the ground on which the State House stands belonged to John Hancock, the commonwealth’s first elected governor (1780–85), who used it to pasture his livestock.

Beacon Hill, located behind it, was the tallest of Boston’s three once-prominent hills (linked by Tremont Street). Its name refers to the simple wooden alarm signal that was erected nearby in 1634. The hill once rose 60 feet higher. In the early 19th century, Hancock’s heirs sold its top as fill for the millpond that lay at the base of its northern slope.

In 1787, newly back from studying architecture in Europe, Charles Bulfinch submitted plans for the new State House. Nine years later, on July 4, Paul Revere and acting governor Samuel Adams officiated at a highly ceremonial laying of the building’s first cornerstone.

From the State House, the Freedom Trail heads south to the corner of Beacon and Tremont streets, where a granary once stood. Deemed inappropriate for the neighborhood after the gilded State House was completed, the granary was demolished and replaced with the Park Street Church. Thus, the humble granary where, among heaps of wheat and barley, the sails of the USS Constitution were cut and sewn was lost. But history continues, for in this evangelical Christian parish on July 4, 1829, William Lloyd Garrison gave a radical speech condemning slavery.

Although a place where the dead are interred, the Granary Burial Ground is where Boston’s greatest historical figures come to life. Here tombstones for John Hancock, Peter Faneuil, Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and the five victims of the Boston Massacre powerfully demonstrate that these indeed great men were mortal after all.

Continuing east to School Street, the trail arrives at King’s Chapel, situated beside Boston’s oldest cemetery. In 1688, finding no other available space, the governor of the Dominion of New England, Edmund Andros, seized this public land and built a wooden Anglican church beside the graves of prominent puritans, including Governor John Winthrop and Mary Chilton, said to be the first person to step ashore from the Mayflower. In 1689 the colonists, who had long despised Andros, deposed and arrested him.

After examining the fantastic carvings of skeletons brandishing swords at the Grim Reaper on many of the gravestones found in this burial ground, backtrack to School Street and proceed past Old City Hall (once the site of the Boston Latin School) to the Old Corner Bookstore, which faces Washington Street.

The white brick building with a double-pitch roof, still known as the Old Corner Bookstore, was once the address of Ticknor and Fields, the publisher of Walden, The Scarlet Letter, and Hiawatha.

Notably, only one other building ever occupied this spot—the home of Anne Hutchinson, who was banished from Massachusetts in 1638. Her crime was to hold Bible study classes explicitly for women at her house. In time, John Winthrop, the presiding judge of the General Court, condemned her actions in a civil trial in which he described her meetings as “a thing not tolerable nor comely in the sight of God, nor fitting for [her] sex.”

Next, cross Washington Street and hike west several yards to the Old South Meeting House—one of the most important sites of the Revolution. Protesters gathered here following the Boston Massacre, and on December 16, 1773, 7,000 fiery citizens mobbed outside the building to condemn the Tea Act. Shortly thereafter, seizing on this collective passion, Samuel Adams organized the Boston Tea Party.

Before continuing on the Freedom Trail, walk a few steps up Milk Street (to the right of the Old South Church) to number 17. Benjamin Franklin was born in a modest house at this location on January 17, 1706.

From the Old Meeting House, hike north on Washington Street to the Old State House. Looking somewhat quaint now, with modern Boston built up around it, this brick building with a lion on one side and a unicorn on the other (both statues were replaced in 1882) was once Boston’s most prominent edifice. Standing on the balcony here on July 18, 1776, Colonel Thomas Crafts read the Declaration of Independence to a triumphant crowd. Lighting bonfires in celebration, citizens burned reminders of the British rule, including the original lion and unicorn.

Proceeding farther north, the trail leads to a marketplace built in 1742 as a gift to Boston by Peter Faneuil. Of Huguenot descent, Faneuil inherited a great fortune from an uncle; with one stipulation—Faneuil had to remain a bachelor or forfeit the money. To appease those resistant to the market, Faneuil elected to include a public meeting hall. In 1763 James Otis dedicated the room to the “Cause of Liberty.” Centuries later, the hall is still an important meeting place; this is where in 1960 John F. Kennedy made his last campaign speech.

Continuing on the same trajectory, the trail passes along the Blackstone Block on Union Street. The names of the little cobblestone passageways—Marsh Lane, Creek Square, Salt Lane, to name some—bespeak the locale’s age and original character. The Union Oyster House, at the end of the block, is both hard to miss and hard to pass up. Louis-Philippe, the eventual king of France, lived here in the 1790s when in exile—reportedly giving French lessons to while away the time!

Turning the corner on Hanover Street, the Freedom Trail passes through a marketplace now called simply “Haymarket.” Filled with vendors selling everything from flounder to artichoke and havarti (Fridays and Saturdays), the market has been alive and well since Boston’s founding.

Beyond Blackstone Street, Hanover Street crosses the site of Boston’s “Big Dig,” now the Rose Kennedy Greenway. Follow the Freedom Trail (marked red) as it jogs left to Salem Street then back to Hanover, to reach the “Isle of North Boston” or “the North End,” as it is called today.

In the early days, its residents relied on two drawbridges to cross Mill Creek, which flowed between the isle and the mainland. Having a colorful history in its own right, the neighborhood shifted from being quiet and upright to being dangerously raucous as Boston’s port prospered and grew after the Revolution. Settled by Irish immigrants, Eastern European Jews, and, in most recent decades, Italians, the neighborhood is ever evolving.

From Hanover Street, the trail turns right onto Richmond Street—“The Black Hole”—as it was called in the 1830s when people came here to gamble and indulge in carnal pleasures.

Reaching North Street (which follows the original shoreline), the trail bears left to pass two noteworthy houses, the Pierce-Hichborn House and the House of Paul Revere. Built in 1680, 50 years after Boston’s founding, Paul Revere’s house stands where the childhood home of Cotton Mather stood before a fire consumed it and 44 other residences in 1676.

Follow the trail left at Prince Street to pass Mariner’s House and, shortly after, turn right to rejoin Hanover Street. Ahead, at the Bulfinch-designed St. Stephen’s Church (where Rose Kennedy was baptized), the trail bears left to continue west through the Paul Revere Mall to the Old North Church (officially, Christ Church in Boston). This church merits a book of its own—its claim to fame is its contribution to the launching of the Revolution, for it was from the steeple of the Old North Church that Paul Revere’s comrades Robert Newman and Captain Pulling sent a signal to Charlestown to warn of British aggression.

Continuing toward Charlestown, the Freedom Trail climbs uphill to another burial ground—this one named for the man who sold it to the Puritans—the shoemaker William Copp. Aside from Increase and Cotton Mather, few of the people buried here are well-known. However, the cemetery boasts many interesting epitaphs, ranging from quite peculiar to poignant. One reads, “Stop here my friend & cast an Eye, As you are now, so was I, As I am now, so you must be, Prepare for Death and follow Me.”

After leaving the cemetery, follow the trail down Hull Street, go left on Commercial Street, then cross the Charlestown Bridge (first opened in 1786). From Chelsea Street in Charlestown, the trail makes a loop. Those concerned with getting to the USS Constitution in time for a tour (the last one is at 3:30 p.m.) should hike to the right. Otherwise, cross the street to City Square.

When a group of Puritans left Salem seeking ever greener pastures, they settled here on “Mishawum.” On this central spot, then called “Market Square,” they erected “The Great House,” which served as the seat of government and the home of Governor Winthrop—but only temporarily—since the area lacked potable water. Lured by the springs of Shawmut, Winthrop and company soon crossed the river for good.

From the square, follow the trail along Main Street to Winthrop Street, which leads north to Monument Square at the top of “Breeds Hill,” where the (misnamed) pivotal Battle of Bunker Hill occurred on June 17, 1775.

The Bunker Hill Monument is the last official site on the Freedom Trail, but round out the tour with a visit to the USS Constitution. To get there, follow the red line back to Winthrop Square then on to the Charlestown Navy Yard.

After taking in marvelous “Old Ironsides”—as she was nicknamed for the impenetrability of her hull hewn of live oak—either backtrack to Boston or get a lift via the MBTA bus line, T, or the water shuttle, which leaves from Pier 4 in the Navy Yard at quarter to and quarter past the hour until 6:15 p.m.

Note: To fully enjoy this hike, it is best to either start early and allow plenty of time for its many historical diversions or plan to complete it over the course of two days.

Maps: Boston’s official visitor information center on Boston Common sells a foldout Freedom Trail map for $2. The Park Service, which has two visitor centers, one at 15 State Street across from the Old State House and another at the Charlestown Navy Yard next to the USS Constitution, offers its own excellent foldout Freedom Trail map free of charge.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

The New England Aquarium (Central Wharf, [617] 973-5200), the Institute of Contemporary Art (100 Northern Avenue, [617] 478-3100), China Town, the Kennedy Library (Columbia Point, [866] JFK-1960), the Science Museum (Science Park, [617] 723-2500), and the Children’s Museum (300 Congress Street, [617] 426-6500) are all located near the Freedom Trail. For those who love wonderful food or sipping espresso while watching soccer among fans cheering in Italian, an extended visit to the North End is a must. One historical site not included on the Freedom Trail is The Boston Tea Party Ship and Museum, anchored at the Congress Street Bridge.