10 PLUM ISLAND: Sandy Point Loop

KEY AT-A-GLANCE INFORMATION

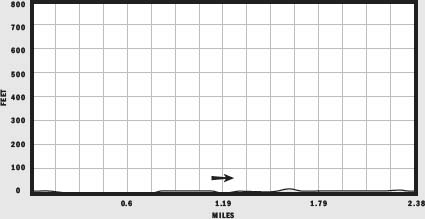

LENGTH: 2.38 miles

CONFIGURATION: Loop

DIFFICULTY: Easy to moderate

SCENERY: Beach and views of the Atlantic Ocean, Ipswich Bay, and salt marshes adjoining Plum Island Sound and the Parker River

EXPOSURE: Full sun

TRAFFIC: Moderate

TRAIL SURFACE: Sand, packed earth, and a short section of paved road

HIKING TIME: 1 hour

SEASON: Year-round sunrise–sunset

ACCESS: Entrance fee is $5 per car, and $2 for people on foot or bicycle.

MAPS: Available at the information center located at the gatehouse; more information and resources are also available at the refuge headquarters, located on Rolfe’s lane just off Plum Island Turnpike.

FACILITIES: Restrooms, information center, public boat launch, and many wildlife observation areas. There are no concession stands on the reservation; however, there are several restaurants and shops located where Plum Island Turnpike meets the northern end of the island.

DRIVING DISTANCE FROM BOSTON COMMON: 38 miles

Plum Island: Sandy Point Loop

UTM Zone (WGS84) 19T

Easting: 353037

Northing: 4733665

Latitude: N 42° 44' 29"

Longitude: W 70° 47' 44"

Directions

From Boston, take Storrow Drive east, following signs for US 1 north. Merge onto US 1 north toward Tobin Bridge/Revere. At 15.1 miles, merge onto I-95 north. From I-95, take Exit 57 and travel east on MA 113 to MA 1A south to the intersection with Rolfe’s Lane and continue 0.5 miles to the end of that road. Turn right onto Plum Island Turnpike and travel 2 miles, crossing the Sargent Donald Wilkinson Bridge to Plum Island. Take the first right onto Sunset Drive and travel 0.5 miles to the refuge entrance.

IN BRIEF

On this exploration of the southernmost tip of Plum Island you will forge your own trail around a drumlin known as Bar Head to reach Ipswich Bluffs (Stage Island). From Stage Island, the Sandy Point Trail leads into the shelter of dunes and salt marsh to complete the loop.

DESCRIPTION

An exclamation point is nothing without the dot below the vertical slash; similarly, Plum Island would not be the 8-mile-long barrier beach it is today without the drumlin poised at its southern tip. Without this static, rounded mound and the several others lined up north of it, the sand and silt caught in the riptides and weather would not have settled here crystal upon crystal to form the island’s silica snake of dunes.

Planetary forces conspired to shape Plum Island 6,000–7,000 years ago. Along with unrelenting wind and waves and earthquakes along the Parker River fault line, subsiding earth and a rising sea level contributed to the island’s creation. Once the beach materialized, the growing gap between the belt of sand and shore gradually filled to form freshwater marsh. Three thousand years ago, the sea level stabilized and for the most part, the island and its beach looked much like it does today—notwithstanding periodic rearrangement by hell-bent nor’easters.

As the area became populated in the decades following the 1635 arrival of Reverend Thomas Parker and company—and as wolves, bears, and Indians grew scarce—settlers ventured to the island with their rifles and cattle. Besides good grazing, thatch for their roofs, and teeming waterfowl, they discovered enormous quantities of beach plums. These they must have been especially happy about—despite the fruit’s near mouth-blistering tartness—as they immediately came to call the sliver of land Plum Island.

Though apparently of little consequence to citizens of Ipswich and Newbury, Plum Island and all the land along the Atlantic from the Naumkeag River (Salem) to the Merrimack had in 1621 been granted to Captain John Mason by the president and council of Plymouth. Regardless, from the earliest days, Plum Island (“Isle Mason,” to the Plymouth officials) was viewed as common land by the General Court and was made available to settlers of Ipswich, Newbury, and Rowley.

Captain Mason, it seems, was too distracted to notice or care. When Reverend Parker and company were investing their hearts and souls in their new settlement upriver from Ipswich, Mason was at work securing his right to an even larger territory north of the Merrimack, a holding he christened New Hampshire.

In any case, settlers were soon squabbling over their own rights to the land. On March 15, 1649, acting on concerns for the economic viability of his settlement, Parker petitioned the General Court to grant all of Plum Island to Newbury. After eight months of rumination, the court finally ruled that the island should be divided into fifths, two fifths went to Ipswich, one to Rowley, and two fifths to Newbury. The island’s fertile southernmost end and Sandy Point officially became part of Ipswich.

In the early days, aside from free-range pigs and other assorted livestock, Plum Island had few year-round residents. However, as is frequently the case with remote places, the island attracted seasonal hunters as well as those on the fringe.

At the end of the 1600s, a certain Elizabeth Perkins and her husband, Luke, settled around the bend from Bar Head on Grape Island to escape persecution from Ipswich mainlanders. The couple’s ordeal began when Elizabeth was taken to court for accusing their minister of immorality and for speaking unflatteringly of her parents; for this, she was accused of being “a virulent, reproachful and wicked-tongued woman.” Though the sound whipping to which she was sentenced was commuted to a three-pound fine, the Perkinses found that they had had enough of town life and set off for the island.

In 1769 Newbury and Newburyport combined resources and built a hospital, or “pest house,” on the northern end of the island so that ships could drop off sailors stricken with smallpox or yellow fever before sailing on to Newburyport’s harbor. Effectively quarantined, ill sailors were ordered to bury their clothes and other “soft goods” in the sand for nine days and to stay out of town until they either succumbed or were declared rid of disease.

As told by Nancy V. Weare in Plum Island: The Way It Was, besides the farmers who set up homesteads on such fertile glacial deposits as the Knobbs, Grape Island, and Cross Farm Hill, day-trippers and summertime vacationers populated the southern end of the island in increasing numbers from the late 19th century to the end of the 1920s. And all the while there were plenty of “gunners” getting away from it all as they set up in camps and bagged rack after rack of waterfowl. In 1881 Mr. Emerson, the proprietor of the Ipswich Bluffs hotel, claimed he killed 40 birds with just two shotgun blasts.

The place of many a grand plan, it is as much by luck as by sheer good sense that rather than being developed as a resort or residential community, the bulk of Plum Island was conserved as a wildlife refuge and park. By the 1890s the bird population was clearly in freefall as a result of year-round hunting and the loss of nesting grounds to development. So, in 1929, when a Stoneham woman named Annie Hamilton Brown willed a hefty sum to the Federation of Bird Clubs of New England the federation set to work purchasing tracts of Plum Island.

Working in tandem with the Massachusetts Audubon Society (with which it eventually merged) the federation succeeded in acquiring all the southern end of the island but Grape Island and Sandy Point (which is now state owned). By offering $5 an acre for adjoining marshland, they managed to expand their holdings westward as well.

Regrettably, Annie Brown’s tremendous foresight and generosity are unknown to most because in 1943 Audubon sold the 1,600-acre Annie H. Brown Wildlife Sanctuary to the federal government, allowing it to merge with the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge.

From the Sandy Point Reservation parking area behind Bar Head, set out hiking east on the wide path that leads through dunes to the beach. With the ocean in full view, bear right and choosing a course through the many boulders, tree trunks, and other often curious tidal detritus, hike south toward the drumlin of Castle Hill, across the bay.

The boulders protruding from the sand and sea on the beach east of Bar Head are known as Emerson’s Rocks. Being encrusted with barnacles and slick with seaweed, the exposed rocks are menacing enough, but when hidden by surf at high tide they are positively murderous.

Between 1772 and 1936, no fewer than 55 ships wrecked off Plum Island. Of these, 10 were dashed to pieces at Emerson Rocks. At least 27 more vessels—schooners, trawlers, and steamers—went down near the mouth of the Merrimack River. The treacherous Ipswich Bay channel claimed at least eight ships as they tried to enter Plum Island Sound from Ipswich Bay. Indeed, Newbury native Samuel Sewell (of Salem Witch Trail fame) wrote in his journal of getting stranded overnight at Sandy Point when he attempted to sail the strait against the wind in an ebbing tide.

Where the slope of Bar Head slides to meet marsh and dune on the neck’s western side, ships, or “sand droghers,” once loaded sand to be used for mortar in Boston. In the late 1800s, when this industry was at its height, each man of the three- to five-man crew was expected to move 50 tons of sand in the space of two tides.

When bearing west round the ‘point, take care not to get trapped on the wrong side of a channel as the tide pours in—otherwise, be resigned to getting wet feet and possibly a drenching.

Documented finds along this stretch where the wind howls over the finger of upland called Ipswich Bluffs add credence to legends that pirates buried treasure in these parts. In 1907 the islander Albert Leet, of the lifesaving team stationed at the Knobbs made two exciting finds—the first was a silver coin dated 1749, then several days later more silver. Another summer resident found silver buckles apparently of ancient Spanish design close to where Leet had discovered the money.

Where the tree-covered upland of the Bluffs begins, a sign sends hikers north, away from the beach, to Stage Island. Take this turn and follow the lightly worn footpath into the shelter of brush. The trail is vague in places but generally cuts a line between the Stage Island estuary and dunes drifted against the western side of the Bar Head drumlin.

Although the wolves that once denned here are gone and the cacophony of honks and quacks from inconceivable numbers of game birds has been hushed, the wildness of the place is largely restored. Ancestors of the fox that darted away as British troops fighting in the War of 1812 came ashore to butcher an islander’s cow live on, hunting voles and field mice at dusk; but barely a hint remains of the soldiers and farmsteading sea captains.

Where the Sandy Point Trail reaches the iron gate by a parking area beside upland and beach, cross the pavement, bearing left to follow the drive back to the entrance of the Sandy Point Reservation.

Note: Due to efforts to save the piping plover from extinction, nearly all of Plum Island’s beach is closed every year from April 1 to August 31, but Sandy Point State Reservation remains open year-round. A hike on Sandy Point begins with the 8-mile drive from the reservation’s entrance gate to the trailhead. Though slow, and dusty during dry summer months, the drive can be something of a safari—those on the alert are likely to spot a good deal of wildlife, some of it quite rare, such as the snowy owls which sometimes stop by in the spring, fall, and winter.

Wheelchair Access: A small section of trail located off the southernmost parking area (7) is specially designed for wheelchair users. In addition, Pines Trail (located at parking area 5) and many of the wildlife observation areas are wheelchair accessible.

NEARBY ATTRACTIONS

The town of Newburyport boasts an assortment of attractions, including many historic homes listed on the National Register of Historic Places. An historic locale of unique appeal to boat lovers is Lowell’s Boat Shop, located in nearby Amesbury. The boat shop opened for business in 1793 and has been producing dories continuously ever since. For information about the boat shop, call (978) 388-0162. For information, schedules, and listings of special events, visit www.historicnewengland.org.

Though steeped in history, Newburyport is a vibrant commercial and cultural center with many excellent restaurants. The town’s independent cinema, The Screening Room, shows films frequently overlooked by mainstream megaplexes. To check show times call (978) 462-3456 or consult the Web site: www.newburyportmovies.com.